SMS Hannover

SMS Hannover on a postcard in 1906.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Hannover |

| Namesake | Province of Hanover |

| Builder | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down | 7 November 1904 |

| Launched | 29 September 1905 |

| Commissioned | 1 October 1907 |

| Fate | Scrapped between 1944 and 1946 in Bremerhaven |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 127.60 m (418 ft 8 in) |

| Beam | 22.20 m (72 ft 10 in) |

| Draft | 8.21 m (26 ft 11 in) |

| Propulsion | 17,524 ihp (13,068 kW), three shafts |

| Speed | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 4,520 nmi (8,370 km; 5,200 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Hannover[a] ("His Majesty's Ship Hannover") was the second of five Template:Sclass- pre-dreadnoughts of the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine). Hannover and the three subsequently constructed ships differed slightly in both design and construction from the lead ship Deutschland in their propulsion systems and slightly thicker armor. Hannover was laid down in November 1904 and commissioned into the High Seas Fleet in October 1907; this was ten months after the revolutionary "all-big-gun" HMS Dreadnought was commissioned into the Royal Navy. As a result, Hannover was obsolete as a capital ship before she was even completed; Dreadnought's more powerful main battery and higher speed would have made it unwise for a ship like Hannover to engage her in the line of battle. The ship was named after the Prussian province of Hannover, now in Lower Saxony.

Hannover and her sisters saw extensive service with the fleet. The ship took part in all major training maneuvers until World War I broke out in July 1914. Hannover and her sisters were immediately pressed into guard duties in the mouth of the Elbe River while the rest of the fleet mobilized. The ship took part in a number of fleet advances, which culminated in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916. During the battle, Hannover served as the flagship for the IV Division of the II Battle Squadron. After Jutland, Hannover and her three surviving sisters were removed from active duty with the fleet to serve as guard ships. In 1917, Hannover was briefly used as a target ship before being returned to guard duties in the Baltic Sea. The ship was decommissioned in December 1918, shortly after the end of the war.

Hannover was brought back to active service in the Reichsmarine, the post-war Germany navy. She served with the fleet for ten years, from 1921 to 1931, before she was again decommissioned. The navy planned to convert the ship into a radio-controlled target ship for aircraft, but this was never carried out. The ship was ultimately broken up for scrap between 1944 and 1946 in Bremerhaven. Her bell is preserved at the Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr in Dresden.

Construction

Hannover was intended to fight in the German battle line with the other battleships of the High Seas Fleet.[1] The ship was laid down on 7 November 1904 at the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Wilhelmshaven.[2] She was launched on 29 May 1905 and commissioned for trials on 1 October 1907, but the fleet exercises in the Skagerrak in November interrupted the trials.[3] Trials resumed after the maneuvers were completed, and by 13 February 1908 Hannover was ready to join the active fleet. She was assigned to the II Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet, joining her sisters Deutschland and Pommern.[4] However, the new British battleship HMS Dreadnought—armed with ten 12-inch (30.5 cm) guns—was commissioned in December 1906, well before Hannover entered service.[5] Dreadnought's revolutionary design rendered obsolete every ship of the German navy, including the brand-new Hannover.[6][b]

Hannover was 127.60 m (418 ft 8 in) long, had a beam of 22.20 m (72 ft 10 in), and a draft of 8.21 m (26 ft 11 in). She had a full-load displacement of 14,218 metric tons (13,993 long tons). The ship was equipped with triple expansion engines that produced a rated 17,524 indicated horsepower (13,068 kW) and a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). At a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), she could steam for 4,520 nautical miles (8,370 km; 5,200 mi).[2]

The ship's primary armament consisted of four 28 cm (11 in) SK L/40 guns in two twin turrets.[c] She was also equipped with fourteen 17 cm (6.7 in) guns mounted in casemates and twenty 8.8 cm (3.46 in) guns in pivot mounts. The ship was also armed with six 45 cm (17.72 in) torpedo tubes, all of which were submerged in the hull.[7]

Service

Upon her commissioning, Hannover joined the II Battle Squadron. From May to June 1908, Hannover took part in maneuvers in the North Sea. From the following month until August, the fleet conducted a training cruise into the Atlantic. During the cruise, Hannover stopped in Punta Delgado in the Azores from 23 July to 1 August.[3] The annual autumn exercises began in September; after these were completed Hannover was transferred to the I Squadron, where she served as the flagship for two years. In November, fleet and unit exercises were conducted in the Baltic Sea.[8]

The training regimen in which Hannover participated followed a similar pattern over the next five years. This included another cruise into the Atlantic, from 7 July to 1 August 1909.[9] February 1910 saw the I Squadron conduct individual training in the Baltic. The unit was subsequently transferred from Kiel to the base in Wilhelmshaven on 1 April. Fleet maneuvers were conducted shortly thereafter, followed by a summer cruise to Norway, and additional fleet training in the fall. On 3 October 1911, the ship was transferred back to the II Squadron. Due to the Agadir Crisis in July, the summer cruise only went into the Baltic. On 14 July 1914, the annual summer cruise to Norway began, but the threat of war in Europe caused the excursion to be cut short; within two weeks Hannover and the rest of the II Squadron had returned to Wilhelmshaven.[8]

World War I

Following the outbreak of World War I, Hannover was tasked with guard duty in the Altenbruch roadstead in the mouth of the Elbe River during the period of mobilization for the rest of the fleet. In late October, the ships were sent to Kiel to have modifications made to their underwater protection systems to make them more resilient. Hannover then joined the battleship support for the battlecruisers that bombarded Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby on 15–16 December 1914.[8] During the operation, the German battle fleet of some 12 dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts came to within 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) of an isolated squadron of six British battleships. However, skirmishes between the rival destroyer screens convinced the German commander, Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, that he was confronted with the entire Grand Fleet, and so he broke off the engagement and turned for home.[10]

Hannover put to sea during the Battle of Dogger Bank on 24 January 1915 to support the beleaguered German battlecruisers, but quickly returned to port. On 17–18 April, Hannover supported a minelaying operation off the Swarte Bank by the light cruisers of the II Reconnaissance Group. A fleet advance to the Dogger Bank followed on 21–22 April. On 16 May, Hannover was sent to Kiel to have one of her 28 cm guns replaced. The ship returned to Kiel on 28 June to have supplemental oil firing installed for her boilers; work lasted until 12 July. On 11–12 September, II Reconnaissance Group conducted another minelaying operation off the Swarte Bank with Hannover and the rest of II Squadron in support. This was followed by another resultless sweep by the fleet on 23–24 October. During the fleet advance of 5–7 March 1916, Hannover and the rest of II Squadron remained in the German Bight, ready to sail in support. They then rejoined the fleet during the operation to bombard Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April.[8] During this operation, the battlecruiser Seydlitz was damaged by a British mine and had to return to port prematurely. Visibility was poor, so the operation was quickly called off before the British fleet could intervene.[11]

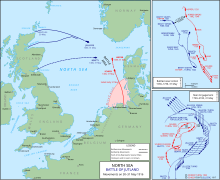

Battle of Jutland

Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the commander of the German fleet, immediately planned another advance into the North Sea, but the damage to Seydlitz delayed the operation until the end of May.[12] Hannover was the flagship in the IV Division of the II Battle Squadron, which was positioned at the rear of the German line. The II Battle Squadron was commanded by Rear Admiral Franz Mauve.[13] During the "Run to the North", Scheer ordered the fleet to pursue the retreating battleships of the British V Battle Squadron at top speed. Hannover and her sisters were significantly slower than the faster dreadnoughts and quickly fell behind.[14] During this period, Scheer directed Hannover to place herself at the rear of the German line, so he would have a flagship on either end of the formation.[15] By 19:30, the Grand Fleet had arrived on the scene and confronted Scheer with significant numerical superiority.[16] The German fleet was severely hampered by the presence of the slower Deutschland-class ships; if Scheer ordered an immediate turn towards Germany, he would have to sacrifice the slower ships to make good his escape.[17]

Scheer decided to reverse the course of the fleet with the Gefechtskehrtwendung, a maneuver that required every unit in the German line to turn 180° simultaneously.[18] As a result of their having fallen behind, the ships of the II Battle Squadron could not conform to the new course following the turn.[19] Hannover and the other five ships of the squadron therefore were located on the disengaged side of the German line. Mauve considered moving his ships to the rear of the line, astern of the III Battle Squadron dreadnoughts, but decided against it when he realized the movement would interfere with the maneuvering of Admiral Franz von Hipper's battlecruisers. Instead, he attempted to place his ships at the head of the line.[20]

Later on the first day of the battle, the hard-pressed battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group were being pursued by their British opponents. Hannover and the other so-called "five-minute ships" came to their aid by steaming in between the opposing battlecruiser squadrons.[21][d] The ships were very briefly engaged, owing in large part to the poor visibility. Hannover fired eight rounds from her 28 cm guns during this period.[21] The British battlecruiser HMS Princess Royal fired on Hannover several times until the latter was obscured by smoke. Hannover was struck once by fragments from one of the 13.5-inch (34 cm) shells fired by Princess Royal.[22] Mauve decided it would be inadvisable to continue the fight against the much more powerful battlecruisers, and so ordered an 8-point turn to starboard.[23]

Late on the 31st, the fleet organized for the night march back to Germany; Deutschland, Pommern, and Hannover fell in behind König and the other dreadnoughts of the III Battle Squadron towards the rear of the line.[24] Hannover was then joined by the Hessen, Schlesien, and Schleswig-Holstein.[25] Hessen situated herself between Hannover and Pommern, while the other two ships fell in at the rear of the line.[26] Shortly after 01:00, the leading ships of the German line came into contact with the armored cruiser HMS Black Prince; Black Prince was quickly destroyed in a hail of gunfire from the German dreadnoughts. Nassau was forced to heel out of line to avoid the sinking British ship, and an hour later rejoined the formation directly ahead of Hannover.[27] At around 03:00, British destroyers conducted a series of attacks against the fleet, some of which targeted Hannover.[28] Shortly thereafter, Pommern was struck by at least one torpedo from the destroyer Onslaught; the hit detonated an ammunition magazine which destroyed the ship in a tremendous explosion. Hannover was astern of Pommern and was forced to turn hard to starboard in order to avoid the wreck. Simultaneously, a third torpedo from Onslaught passed closely astern of Hannover, which forced the ship to turn away.[29] Shortly after 04:00, Hannover and several other ships fired repeatedly at what were thought to be submarines; in one instance, the firing from Hannover and Hessen nearly damaged the light cruisers Stettin and München, which prompted Scheer to order them to cease firing.[30] Hannover and several other ships again fired at imaginary submarines shortly before 06:00.[31]

Despite the ferocity of the night fighting, the High Seas Fleet punched through the British destroyer forces and reached Horns Reef by 04:00 on 1 June.[32] The German fleet reached Wilhelmshaven a few hours later, where the undamaged dreadnoughts of the Template:Sclass- and Template:Sclass-es took up defensive positions.[33] Over the course of the battle, Hannover had fired eight 28 cm shells, twenty-one 17 cm rounds, and forty-four shells from her 8.8 cm guns.[34] She emerged from the battle completely unscathed.[8]

Later actions

After Jutland, Hannover went into dock for periodic maintenance on 4 November. Hannover and the rest of II Battle Squadron were then detached from the High Seas Fleet on 30 November and reassigned to picket duty in the mouth of the Elbe. In early 1917, Hannover was used as a target ship in the Baltic. On 21 March, Hannover had some of her guns removed; the ship was then converted into a guard ship from 25 June to 16 September. During this period, on 15 August, the II Battle Squadron was officially disbanded. On 27 September, Hessen was assigned to guard duties in the Baltic, where she replaced the older battleship Lothringen.[35]

Postwar service

On 11 November 1918, Germany entered into the Armistice with the Western Allies. According to the terms of the Armistice, the most modern components of Germany's surface fleet were interned in the British naval base at Scapa Flow, while the rest of the fleet was demilitarized.[36] On the day the armistice took effect, Hannover was sent briefly to Swinemünde, before returning to Kiel on 14–15 November along with Schlesien. Hannover was decommissioned a month later on 17 December in accordance with the terms of the Armistice.[35]

The terms of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on 21 June 1919, permitted Germany to retain a surface fleet of eight obsolete battleships. This amounted to three of the Deutschland-class battleships, Hannover, Schleswig-Holstein and Schlesien, as well as the five Template:Sclass-s.[37]

Hannover was the first of all the old battleships to come in service with the Reichsmarine in February 1921 as fleet flagship in the Baltic. Her first homeport was Swinemünde but she was transferred to Kiel in 1922. In 1923 the German Navy adopted a new command structure and Braunschweig became flagship of the Fleet. In October 1925, Hannover was moved to the North Sea station. She was decommissioned in March 1927 when Schlesien returned to active service. With newly built masts but still three funnels she entered service again replacing Elsass in February 1930 until September 1931.[38]

The ship was struck from the naval register in 1936, after which the navy intended to rebuild Hannover for use as a target ship. The conversion, however, never occurred.[39] Ultimately, the ship was broken up between May 1944 and October 1946 in Bremerhaven. Her bell now resides in the Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr in Dresden.[40]

References

Notes

- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German.

- ^ HMS Dreadnought's ten main guns more than doubled the number of heavy guns mounted on Hannover and the other members of her class. The British ship, which was equipped with powerful turbine engines and could steam at a speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph), had a 3-knot advantage over the German vessels. See: Gardiner & Gray, p. 21.

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick-firing, while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 calibers, meaning that the gun is 40 times long as it is in diameter. See: Grießmer, p. 177.

- ^ The men of the German navy referred to ships as "five-minute ships" because that was the length of time they were expected to survive if confronted by a dreadnought. See: Tarrant, p. 62.

Citations

- ^ Herwig, p. 45.

- ^ a b Staff, p. 5.

- ^ a b Staff, p. 10.

- ^ Staff, p. 7–12.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Herwig, p. 57.

- ^ Gröner 1982, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Staff, p. 11.

- ^ Staff, pp. 8, 11.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 58.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 286.

- ^ London, p. 73.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 84.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 150.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 150–152.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 152–153.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 154.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 155.

- ^ a b Tarrant, p. 195.

- ^ Campbell, p. 254.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 241.

- ^ Campbell, p. 275.

- ^ Campbell, p. 294.

- ^ Campbell, p. 290.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 242.

- ^ Campbell, p. 300.

- ^ Campbell, p. 314.

- ^ Campbell, p. 315.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 263.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 292.

- ^ a b Staff, p. 12.

- ^ Armistice, Chapter V.

- ^ Williamson, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Hildebrand, p. 47 f, Vol. 3.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 141.

- ^ Gröner, p. 22.

Bibliography

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8. OCLC 12119866.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9. OCLC 57239454.

- Hildebrand, Hans H. (1979). Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart. Herford: Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft.

- London, Charles (2000). Jutland 1916: Clash of the Dreadnoughts. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-992-8.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918 (1). Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9. OCLC 48131785.

- Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Battleships 1939–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-498-6.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan (2014). "Last of the Line: The German Battleships of the Braunschweig and Deutschland Classes". Warship 2014. London: Conway Maritime Press: 49–69. ISBN 978-1591149231.

![]() Media related to SMS Hannover at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to SMS Hannover at Wikimedia Commons