Salinity

Salinity is the saltiness or dissolved salt content of a body of water (see also soil salinity). Salinity is an important factor in determining many aspects of the chemistry of natural waters and of biological processes within it, and is a thermodynamic state variable that, along with temperature and pressure, governs physical characteristics like the density and heat capacity of the water.

A contour line of constant salinity is called an isohaline – or sometimes isohale.

Definitions

Salinity in rivers, lakes, and the ocean is conceptually simple, but technically challenging to define and measure precisely. Conceptually the salinity is the quantity of dissolved salt content of the water. Salts are compounds like sodium chloride, magnesium sulfate, potassium nitrate, and sodium bicarbonate which dissolve into ions. The concentration of dissolved chloride ions is sometimes referred to as chlorinity. Operationally, dissolved matter is defined as that which can pass through a very fine filter (historically a filter with a pore size of 0.45 μm, but nowadays usually 0.2 μm).[2] Salinity can be expressed in the form of a mass fraction, i.e. the mass of the dissolved material in a unit mass of solution.

Seawater typically has a salinity of around 35 g/kg, although lower values are typical near coasts where rivers enter the ocean. Rivers and lakes can have a wide range of salinities, from less than 0.01 g/kg[3] to a few g/kg, although there are many places where higher salinities are found. The Dead Sea has a salinity of more than 200 g/kg.[4]

Whatever pore size is used in the definition, the resulting salinity value of a given sample of natural water will not vary by more than a few percent (%). Physical oceanographers working in the abyssal ocean, however, are often concerned with precision and intercomparability of measurements by different researchers, at different times, to almost five significant digits.[5] A bottled seawater product known as IAPSO Standard Seawater is used by oceanographers to standardize their measurements with enough precision to meet this requirement.

Composition

Measurement and definition difficulties arise because natural waters contain a complex mixture of many different elements from different sources (not all from dissolved salts) in different molecular forms. The chemical properties of some of these forms depend on temperature and pressure. Many of these forms are difficult to measure with high accuracy, and in any case complete chemical analysis is not practical when analyzing multiple samples.[clarification needed] Different practical definitions of salinity result from different attempts to account for these problems, to different levels of precision[clarification needed], while still remaining reasonably easy to use.

For practical reasons[clarification needed] salinity is usually related to the sum of masses of a subset of these dissolved chemical constituents (so-called solution salinity), rather than to the unknown mass of salts that gave rise to this composition (an exception is when artificial seawater is created). For many purposes this sum can be limited to a set of eight major ions in natural waters,[6][7] although for seawater at highest precision an additional seven minor ions are also included.[5] The major ions dominate the inorganic composition of most (but by no means all) natural waters. Exceptions include some pit lakes and waters from some hydrothermal springs.

The concentrations of dissolved gases like oxygen and nitrogen are not usually included in descriptions of salinity.[2] However, carbon dioxide gas, which when dissolved is partially converted into carbonates and bicarbonates, is often included. Silicon in the form of silicic acid, which usually appears as a neutral molecule in the pH range of most natural waters, may also be included for some purposes (e.g., when salinity/density relationships are being investigated).

Seawater

The term 'salinity' is, for oceanographers, usually associated with one of a set of specific measurement techniques. As the dominant techniques evolve, so do different descriptions of salinity. The distinctions between these different descriptions are important to physical oceanographers but are obscure and confusing to nonspecialists.

Salinities were largely measured using titration-based techniques before the 1980s. Titration with silver nitrate could be used to determine the concentration of halide ions (mainly chlorine and bromine) to give a chlorinity. The chlorinity was then multiplied by a factor to account for all other constituents. The resulting 'Knudsen salinities' are expressed in units of parts per thousand (ppt or ‰).

The use of electrical conductivity measurements to estimate the ionic content of seawater led to the development of the so-called practical salinity scale 1978 (PSS-78).[8][9] Salinities measured using PSS-78 do not have units. The suffix psu or PSU (denoting practical salinity unit) is sometimes added to PSS-78 measurement values, however this practice is officially discouraged.[10]

In 2010 a new standard for the properties of seawater was introduced, the so-called thermodynamic equation of seawater 2010 (TEOS-10).[5] This standard includes a new scale, the so-called reference composition salinity scale. Absolute salinities on this scale are expressed as a mass fraction, in grams per kilogram of solution. Salinities on this scale are determined by combining electrical conductivity measurements with other information that can account for regional changes in the composition of seawater. They can also be determined by making direct density measurements.

A sample of seawater from most locations with a chlorinity of 19.37 ppt will have a Knudsen salinity of 35.00 ppt, a PSS-78 practical salinity of about 35.0, and a TEOS-10 absolute salinity of about 35.2 g/kg. The electrical conductivity of this water at a temperature of 15 °C is 42.9 mS/cm.[5][11]

Lakes and rivers

Limnologists and chemists often define salinity in terms of mass of salt per unit volume, expressed in units of mg per litre or g per litre.[6] It is implied, although often not stated, that this value applies accurately only at some reference temperature. Values presented in this way are typically accurate to of the order of 1%. Limnologists also use electrical conductivity, or "reference conductivity", as a proxy for salinity. This measurement may be corrected for temperature effects, and is usually expressed in units of μS/cm.

A river or lake water with a salinity of around 70 mg/L will typically have a specific conductivity at 25 °C of between 80 and 130 μS/cm. The actual ratio depends on the ions present.[12] The actual conductivity usually changes by about 2% per degree Celsius, so the measured conductivity at 5 °C might only be in the range of 50–80 μS/cm.

Direct density measurements are also used to estimate salinities, particularly in highly saline lakes.[4] Sometimes density at a specific temperature is used as a proxy for salinity. At other times an empirical salinity/density relationship developed for a particular body of water is used to estimate the salinity of samples from a measured density.

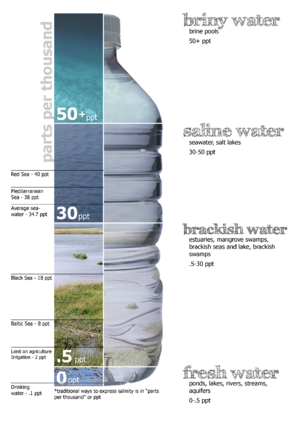

| Water salinity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh water | Brackish water | Saline water | Brine |

| < 0.05% | 0.05 – 3% | 3 – 5% | > 5% |

| < 0.5 ‰ | 0.5 – 30 ‰ | 30 – 50 ‰ | > 50 ‰ |

Systems of classification of water bodies based upon salinity

| Thalassic series |

| >300 |

| hyperhaline |

| 60–80 |

| metahaline |

| 40 |

| mixoeuhaline |

| 30 |

| polyhaline |

| 18 |

| mesohaline |

| 5 |

| oligohaline |

| 0.5 |

Marine waters are those of the ocean, another term for which is euhaline seas. The salinity of euhaline seas is 30 to 35. Brackish seas or waters have salinity in the range of 0.5 to 29 and metahaline seas from 36 to 40. These waters are all regarded as thalassic because their salinity is derived from the ocean and defined as homoiohaline if salinity does not vary much over time (essentially constant). The table on the right, modified from Por (1972),[13] follows the "Venice system" (1959).[14]

In contrast to homoiohaline environments are certain poikilohaline environments (which may also be thalassic) in which the salinity variation is biologically significant.[15] Poikilohaline water salinities may range anywhere from 0.5 to greater than 300. The important characteristic is that these waters tend to vary in salinity over some biologically meaningful range seasonally or on some other roughly comparable time scale. Put simply, these are bodies of water with quite variable salinity.

Highly saline water, from which salts crystallize (or are about to), is referred to as brine.

Environmental considerations

Salinity is an ecological factor of considerable importance, influencing the types of organisms that live in a body of water. As well, salinity influences the kinds of plants that will grow either in a water body, or on land fed by a water (or by a groundwater).[16] A plant adapted to saline conditions is called a halophyte. A halophyte which is tolerant to residual sodium carbonate salinity are called glasswort or saltwort or barilla plants. Organisms (mostly bacteria) that can live in very salty conditions are classified as extremophiles, or halophiles specifically. An organism that can withstand a wide range of salinities is euryhaline.

Salt is expensive to remove from water, and salt content is an important factor in water use (such as potability).

The degree of salinity in oceans is a driver of the world's ocean circulation, where density changes due to both salinity changes and temperature changes at the surface of the ocean produce changes in buoyancy, which cause the sinking and rising of water masses. Changes in the salinity of the oceans are thought to contribute to global changes in carbon dioxide as more saline waters are less soluble to carbon dioxide. In addition, during glacial periods, the hydrography is such that a possible cause of reduced circulation is the production of stratified oceans. Hence it is difficult in this case to subduct water through the thermohaline circulation.

See also

References

- ^ World Ocean Atlas 2009. nodc.noaa.gov

- ^ a b Pawlowicz, R. (2013). "Key Physical Variables in the Ocean: Temperature, Salinity, and Density". Nature Education Knowledge. 4 (4): 13.

- ^ Eilers, J. M.; Sullivan, T. J.; Hurley, K. C. (1990). "The most dilute lake in the world?". Hydrobiologica. 199: 1–6. doi:10.1007/BF00007827.

- ^ a b Anati, D. A. (1999). "The salinity of hypersaline brines: concepts and misconceptions". Int. J. Salt Lake. Res. 8: 55–70. doi:10.1007/bf02442137.

- ^ a b c d IOC, SCOR, and IAPSO (2010). The international thermodynamic equation of seawater – 2010: Calculation and use of thermodynamic properties. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, UNESCO (English). pp. 196pp.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Wetzel, R. G. (2001). Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems, 3rd ed. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-744760-5.

- ^ Pawlowicz, R.; Feistel, R. (2012). "Limnological applications of the Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater 2010 (TEOS-10)". Limnology and Oceanography: Methods. 10: 853–867. doi:10.4319/lom.2012.10.853.

- ^ Unesco (1981). The Practical Salinity Scale 1978 and the International Equation of State of Seawater 1980. Tech. Pap. Mar. Sci., 36

- ^ Unesco (1981). Background papers and supporting data on the Practical Salinity Scale 1978. Tech. Pap. Mar. Sci., 37

- ^ Millero, F. J. (1993). "What is PSU?". Oceanography. 6 (3): 67.

- ^ Culkin, F.; Smith, N. D. (1980). "Determination of the Concentration of Potassium Chloride Solution Having the Same Electrical Conductivity, at 15C and Infinite Frequency, as Standard Seawater of Salinity 35.0000‰ (Chlorinity 19.37394‰)". IEEE J. Oceanic Eng. OE-5 (1): 22–23. doi:10.1109/JOE.1980.1145443.

- ^ van Niekerk, Harold; Silberbauer, Michael; Maluleke, Mmaphefo (2014). "Geographical differences in the relationship between total dissolved solids and electrical conductivity in South African rivers". Water SA. 40 (1). doi:10.4314/wsa.v40i1.16.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Por, F. D. (1972). "Hydrobiological notes on the high-salinity waters of the Sinai Peninsula". Marine Biology. 14 (2): 111. doi:10.1007/BF00373210.

- ^ Venice system (1959). The final resolution of the symposium on the classification of brackish waters. Archo Oceanogr. Limnol., 11 (suppl): 243–248.

- ^ Dahl, E. (1956). "Ecological salinity boundaries in poikilohaline waters". Oikos. 7 (1). Oikos: 1–21. doi:10.2307/3564981. JSTOR 3564981.

- ^ Kalcic, Maria, Turowski, Mark; Hall, Callie. "Stennis Space Center Salinity Drifter Project. A Collaborative Project with Hancock High School, Kiln, MS". Stennis Space Center Salinity Drifter Project. NTRS. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Mantyla, A.W. 1987. Standard Seawater Comparisons updated. J. Phys. Ocean., 17: 543–548.

- Equations and algorithms to calculate fundamental properties of sea water.

- History of the salinity determination

- Practical Salinity Scale 1978.

- Salinity calculator

- Lewis, E. L. 1982. The practical salinity scale of 1978 and its antecedents. Marine Geodesy. 5(4):350–357.

- Equations and algorithms to calculate salinity of inland waters