Sara Creek (river)

| Sara Creek | |

|---|---|

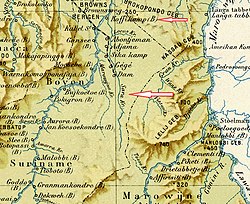

Sara Creek before the construction of the Brokopondo Reservoir (1917) | |

| Native name | Sarakreek (Dutch) |

| Location | |

| Country | Suriname |

| District | Para District |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Lely Mountains |

| • coordinates | 4°13′32″N 54°57′57″W / 4.2256°N 54.9659°W |

| Mouth | Brokopondo Reservoir |

• coordinates | 4°28′14″N 54°55′42″W / 4.4705°N 54.9284°W |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Suriname River→Atlantic Ocean |

Sara Creek (Dutch: Sarakreek) is a former tributary of the Suriname River located in the Para District of Suriname. After the completion of the Afobaka Dam in 1964, the Sara Creek flows into the Brokopondo Reservoir.[1] In 1876, gold was discovered along the Sara Creek, and a railway line from Paramaribo to the river was completed in 1911.

Overview

The Sara Creek was the most important tributary of the Suriname River.[2] It was described as a wide river with many shoals, river islands and rapids.[3] From 1793 onwards, it was settled by the Ndyuka people who constructed ten villages along its shores.[4] The most important settlement was the Federation of Koffiekamp which consisted of three Ndyuka villages and a mission of the Moravian Church. Koffiekamp was located at the confluence of the Sara Creek and the Suriname River.[5]

The villages were a source of contention with the Saramaka Maroons whose territory was the Suriname River south of the military outpost Victoria.[3] The Saramaka considered the Sara Creek part of their territory, because it was a tributary of the Suriname River. The Ndyuka argued that they had moved north from the Tapanahony River.[6] In 1809, a treaty was signed between the Government of Suriname and the Granman of the Ndukya, that the Ndyuka should leave the Sara Creek and move to the Marowijne River instead, however the treaty was ignored.[4]

Discovery of gold

In 1876, gold was discovered along the Sara Creek. By 1882, 587,000 hectares (1,450,000 acres) of concessions were awarded for the exploration of the area,[7] and Governor van Sypesteyn was forced to resign, because he had personally profited from the concessions.[8]

Lawa Railway

In the late 19th century, a boat trip from Paramaribo to the gold fields at the Lawa River took 14 days under normal circumstances.[9] In 1903, railway construction started on the Lawa Railway to improve the access to the gold fields along the Sara Creek and Lawa River.[10] The railway was completed in 1911, and ended at Dam near the last rapids in the Sara Creek.[11] The last 50 kilometres to the Lawa River were never constructed, because the railway construction cost was higher than expected, and the proceeds from the gold fields were below expectation.[12]

The section between the Suriname River and Dam closed in 1930, but reopened during World War II. Even though there was no regular service, the line remained in use by rail push trolleys. On 10 April 1964, the railway line closed for good, and the track along the Sara Creek was flooded by the Brokopondo Reservoir.[13]

Brokopondo Reservoir and aftermath

In 1958, it was decided to built the Afobaka Dam in the Suriname River in order to provide electricity for the aluminium factories. The inhabitants of the villages along the Sara Creek were going to be resettled.[1] In the same year, an agreement was reached between the Surinamese government and the Ndyuka and Saramaka tribes. The Ndyuka could choose their own captains (village chiefs), however they were under the authority of the Saramaka granman (paramount chief).[6] In 1964, the dam was closed and the Brokopondo Reservoir flooded most of the villages.[1] The main village which remains along the river is Lebidoti, a resettlement village on an island near the new mouth of the Sara Creek.[14]

In 1974, gold exploration restarted by the Canadian Canarc Resource Corp.[1] During the Surinamese Interior War, the concession was transferred to Ruben Lie Pauw Sam who founded the Sarakreek Resource Corp NV.[15] In 2016, eight skalians (gold dredges) were given a permit to look for gold in the river by the village of Lediboti for a monthly payment of SRD 80,000 to the village.[16]

References

- ^ a b c d "Distrikt Brokopondo". Suriname.nu (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Benjamins & Snelleman 1917, p. 670.

- ^ a b W.R. van Hoëvell. Slaven en vrijen onder de Nederlandsche wet (in Dutch). Zaltbommel: Joh. Noman en Zoon. p. 25.

- ^ a b Silvia W. de Groot (1970). "Rebellie der Zwarte Jagers". De Gids (in Dutch). p. 303. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Bert Eersteling. "Koffiekamp in historisch perspectief". Werkgroep Carabische Letteren (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Sarakreek weer onder eigen stamgraman". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Goud". Suriname.nu (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Spoorlijnen naar nergens". Geschiedenis.eu (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Surinaamsche Almanak voor het Jaar 1890". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1889. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Benjamins & Snelleman 1917, p. 267.

- ^ Adriaan van Putten (1990). "De Lawa-spoorweg: een voortijdige poging tot industrialisatie". OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis (in Dutch). p. 71. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Alex van Stipriaan (2011). "Marrons en de transport- en communicatierevolutie in het Surinaamse binnenland". OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis (in Dutch). p. 33. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "The Railways of Surinam, 2014 - Suriname Landspoorweg". International Steam. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Sranan. Cultuur in Suriname". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "De 10 golden boys van Suriname". Parbode (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Rusland: "8 skalians kunnen veel grotere ravage in Sarakreek aanrichten"". Dagblad Suriname (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

Bibliography

- Benjamins, Herman Daniël; Snelleman, Johannes (1917). Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch West-Indië (in Dutch). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)