Scottsboro Boys: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Essay-like|article|date=April 2009}} |

{{Essay-like|article|date=April 2009}} |

||

{{Wikify|date=May 2009}} |

{{Wikify|date=May 2009}} |

||

[[Image:Leibowitz, Samuel & Scottsboro Boys 1932.jpg|thumb|The Scottsboro Boys with attorney [[Samuel Leibowitz]] under guard by the State Militia, 1932]] The '''Scottsboro Boys''' were nine black defendants in a 1931 |

[[Image:Leibowitz, Samuel & Scottsboro Boys 1932.jpg|thumb|The Scottsboro Boys with attorney [[Samuel Leibowitz]] under guard by the State Militia, 1932]] The '''Scottsboro Boys''' were nine black defendants in a 1931 RAPE! case initiated in [[Scottsboro, Alabama]]. The case was heard by the [[United States Supreme Court]] twice and the decisions established the principles that criminal defendants are entitled to effective assistance of counsel<ref>{{cite web|url=http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=287&page=45 |title=''Powell v. Alabama'', 287 U.S. 45 (1932) |publisher=Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com |date= |accessdate=2009-09-20}}</ref> and that people may not be ''[[de facto]]'' excluded from juries because of their race.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=294&page=587 |title=''Norris v. Alabama'', 294 U.S. 587 (1935) |publisher=Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com |date=1935-04-01 |accessdate=2009-09-20}}</ref> |

||

Nine young black defendants were accused of [[Types of rape#Gang rape|raping]] two fellow homeless white women on a freight train, and eight were quickly convicted in a mob atmosphere. The juries were entirely white, and the defense attorneys had little experience in criminal law and no time to prepare their cases. As each of the nine cases successively went to the jury, the next trial was immediately begun. All but one of the defendants were found guilty, and these eight were sentenced to death on rape charges. These eight, however, later had their death sentences lifted by the Supreme Court, serving instead between six and nineteen years in prison. |

Nine young black defendants were accused of [[Types of rape#Gang rape|raping]] two fellow homeless white women on a freight train, and eight were quickly convicted in a mob atmosphere. The juries were entirely white, and the defense attorneys had little experience in criminal law and no time to prepare their cases. As each of the nine cases successively went to the jury, the next trial was immediately begun. All but one of the defendants were found guilty, and these eight were sentenced to death on rape charges. These eight, however, later had their death sentences lifted by the Supreme Court, serving instead between six and nineteen years in prison. |

||

Revision as of 17:53, 21 October 2009

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (April 2009) |

| Template:Wikify is deprecated. Please use a more specific cleanup template as listed in the documentation. |

The Scottsboro Boys were nine black defendants in a 1931 RAPE! case initiated in Scottsboro, Alabama. The case was heard by the United States Supreme Court twice and the decisions established the principles that criminal defendants are entitled to effective assistance of counsel[1] and that people may not be de facto excluded from juries because of their race.[2]

Nine young black defendants were accused of raping two fellow homeless white women on a freight train, and eight were quickly convicted in a mob atmosphere. The juries were entirely white, and the defense attorneys had little experience in criminal law and no time to prepare their cases. As each of the nine cases successively went to the jury, the next trial was immediately begun. All but one of the defendants were found guilty, and these eight were sentenced to death on rape charges. These eight, however, later had their death sentences lifted by the Supreme Court, serving instead between six and nineteen years in prison.

In 1976, forty-five years after the first trial, segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace issued a pardon to the one remaining Scottsboro defendant still subject to the Alabama penal system[3]

The arrests

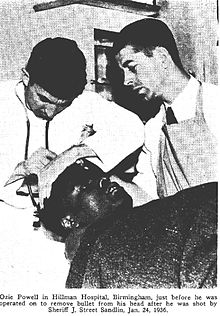

The nine black youths, Olen Montgomery (age 17), Clarence Norris (age 19), Haywood Patterson (age 18), Ozie Powell (age 16), Willie Roberson (age 17), Charlie Weems (age 19), Eugene Williams (age 13), and brothers Andy (age 19) and Roy Wright (age 12) were accused of the rapes of Ruby Bates and Victoria Price on March 25, 1931, on the Southern Railroad line from Chattanooga to Memphis.[4][5] Several people were "hoboing" on the freight train including the nine black youths, two white women, and several white youths. Four of the blacks, Patterson, Williams, and the Wright brothers had hoped to find work hauling logs on the Missouri River. The other black youths on the train were from Georgia and were unacquainted with the other four. The white hobos on the train were also in search of work and included several boys or men and Victoria Price and Ruby Bates. The women were Huntsville, Alabama residents who had gone to Chattanooga, Tennessee to find work in cotton mills. Failing to obtain those jobs, they hopped this freight train back to Huntsville, completely without money.[6]

A fight began between the white youths and the black youths, allegedly when a white youth stepped on Patterson's hand as he hung on to the side of a tank car, just west of the Lookout Mountain tunnel. The off-and-on fight involved name-calling, stone throwing and fisticuffs. Most of the white youths were forced off the slow moving train near Stevenson, Alabama. Several of them told the Stevenson stationmaster about the fight and said they wanted to press charges.[7] The stationmaster called Jackson County Sheriff Matt L. Wann to report the incident. The Sheriff called Deputy Charlie Latham, who lived near the next scheduled stop for the train, Paint Rock, Alabama and told him to deputize as many citizens as he needed to "capture every negro on the train. I am giving you authority to deputize every man you can find."[8] A posse of some fifty white men armed with shotguns, rifles and pistols prepared for their arrival. Even before the slow moving train stopped about 2 p.m., the posse had searched all forty-eight cars. Within ten minutes they had arrested all nine of the "raggedly dressed" black youths at gun point. From the time of their arrest until the first trial twelve days later, none of the boys were permitted to call or speak to anyone, not even each other.[8] The initial arrest was for the assault and attempted murder of the white youths ejected from the train at Stevenson.[9]

The posse was surprised to find Ruby Bates and Victoria Price on the train, dressed in men's overalls covering dresses. When discovered, they scrambled out of the open gondola car used to haul gravel where they had been riding. They ran in the direction of the engine, where they ran into other members of the posse coming the other way. They turned and started to run back in the other direction where other members of the posse stopped them. The older, Victoria Price "appeared to be on the verge of fainting".[10] Seeing that, Deputy Latham ordered some of the men to take them to wait in the shade of a nearby gum tree, while they tied their black charges together and hauled them on the back of a flatbed truck to the two-story jail some twenty miles away in Scottsboro, Alabama.[note 1]

Twenty minutes after the train left Paint Rock, its station agent W. H. Hill asked the women whether any of the "negroes" had bothered them. At that point, Ruby Bates told Hill that they had been raped by them. Agent Hill quickly reported that accusation to Deputy Latham.[11] Upon hearing this accusation, Sheriff Wann sent the women to be examined by two doctors. Scottsboro doctor, R. R. Bridges and his assistant, Dr. John Lynch, examined them within two hours after the alleged rapes. The doctors found semen in the vaginas of both women. Ruby Bates had considerably more than Victoria Price. While they found some scratches and a few bruises, the doctors found little evidence of a violent attack; they found no vaginal tearing for either woman. Bates and Price were arrested and jailed for several days, pending charges of vagrancy. Probably on a tip from the mother of underage Ruby Bates the authorities initially looked into whether Price had violated the Mann Act, which prohibited taking a minor across state lines for "immoral purposes" or prostitution. It was alleged that Victoria Price was a "known prostitute", which led law enforcement to suspect that Price had violated the Mann Act when she left Tennessee for Michigan with Bates.[12] As the focus of law enforcement shifted to the black prisoners, these charges were never filed and the women were released. A widely shown photo shows the two women shortly after the arrests in 1931, still in their hobo dress and still on very friendly terms.

In the Jim Crow South, a black male was said to risk lynching by just looking at a white woman.[13] Word quickly spread and a lynch mob gathered in front of the jail in Scottsboro and prepared to storm the jail. The crowd of farmers with many of their wives and children looking on, grew into the hundreds.[note 2] The newly elected Jackson County Sheriff, Matt L. Wann barricaded the door to the jail. At 8:30 that evening, he decided to move the accused youths to a jail in another community, but could not, because the wires to the headlights on the squad cars had been cut. Mayor James David Snodgrass begged the crowd to leave. However, they refused and demanded that the youths be surrendered to them for immediate lynching.[14] At the request of Sheriff Wann, Alabama Governor Benjamin M. Miller, called in the National Guard to protect the jail.[15] Authorities pleaded against mob violence by promising speedy trials and asking "the Judge to send them to the chair".[16] The editor of the local Scottsboro Progressive Age was very self congratulatory that Scottsboro had not lynched these defendants outright. The editor wrote, "If ever there was an excuse for taking the law into their own hands, surely this was one. Nevertheless, the People of Jackson County have saved the good name of the county and state by remaining cool and allowing the law to take its course."[16]

Trials in Scottsboro

On March 26, National Guardsmen took the defendants to Gadsden, Alabama for safekeeping. On March 30 the accused were indicted by an all-white grand jury. The joint indictment against the nine defendants named only Price as a rape victim. They were then brought back to Scottsboro for arraignment in the Jackson County Circuit Court, where they all pled not guilty. Rape was a capital offense in Alabama at that time. Even so, they were not allowed to communicate with friends or family. They had not consulted with an attorney before the arraignment and had no attorney to represent them at the arraignment. Most of them were illiterate and none had any knowledge at all of criminal law or court procedure. They were returned to Gadsden to protect them while they awaited their trials.

Their trials began on April 6, twelve days after their arrest.[15] About 5:45 a.m. 118 Alabama guardsmen of the 167th Infantry made up of five national guard companies of Gadsden, Albertville and Guntersville, Alabama commanded by Major Joe Starnes, brought the terrified defendants from Gadsden and housed them temporarily in the Scottsboro County Jail until their trials started.

Crowd in front of the courthouse

The trials started on Scottsboro's "Fair Day," the first Monday of each month when area farmers came to town to sell their produce and buy supplies. Other people from the surrounding area also came by car and train that morning to Scottsboro, forming a crowd of thousands by the time the first trial began at 8:30 a.m. The crowd eventually grew to 8,000 - 10,000 whites, who milled around in front of the Court House Square while the trial went on. The crowd became "ugly" or "festive" and "curious", according to different reports. National guardsmen, some armed with machine guns, formed a line around the court house to keep the crowd at bay.[17] No one was allowed into the Courthouse during the trials without a special permit. Males under twenty one and all women were excluded, due to the salacious nature of the testimony expected.[18] As the United States Supreme Court later described this situation, the National Guard "guarded the courthouse and grounds at every stage of the proceedings. It is perfectly apparent that the proceedings, from beginning to end, took place in an atmosphere of tense, hostile, and excited public sentiment. During the entire time, the defendants were closely confined or were under military guard."[19]

Pace of the trials

Jackson County Judge Alfred Hawkins presided at the first four trials before packed standing-room-only, all-white audiences — what the defendants later described as "one big white smiling face". Circuit Solicitor H.G. Bailey was the Prosecutor. Judge Hawkins and Solicitor Bailey gave every indication that they could not get the trials over fast enough in order to quell the community outrage before real violence broke out. The first trial went into a second day, due to the time consumed by the first day by the pretrial motions and the need to decide who was going to be tried with whom, the rest of the trials took place one right after the other and took only a single day to produce one capital conviction after another.

Selection of the Defense Attorneys

Judge Hawkins had broadly ordered all people of the alian land bar to assist the defendants. However, at the time the trials began, no attorney had done so. Ultimately, the youths were defended by the only lawyers the parents could afford: a Chattanooga real estate lawyer, Stephen Roddy, and Milo Moody, a 69-year-old lawyer who had not defended a case at trial in decades.[18] Roddy was neither a member of the Alabama bar nor a criminal defense attorney and was not familiar with the Alabama laws and court rules. Judge Hawkins questioned an unsure Roddy before the first trial about his representation of the defendants. While it does not appear to have been his object, Roddy's responses made it clear to the United States Supreme Court that he had not talked to those defendants until just before the start of the first trial. He informed Judge Hawkins that he was only there informally at the request of friends and family of the accused for which no one had paid him. He frankly admitted on the record in his colloquy with the Court that he had not had time to prepare for trial and that he was not familiar with Alabama law and procedure. In the end, he agreed to appear in the case to aid Moody, who was the only local attorney who would agree to take the case without being forced to do so by Judge Hawkins.[20] He agreed, "I will go ahead and help do anything I can."[21]

Petition for change of venue

The attorney general Roddy petitioned the court for a change of venue, asserting that the crowd would intimidate the jury. Judge Hawkins held a hearing on that petition. Roddy presented the testimony of his clients on the matter, he also presented the case of the girls who supposedily got raped by the boys. He entered into evidence newspaper articles which reported the crowds in the Scottsboro Sentinel, in the Montgomery Advertiser and in the Chattanooga paper. He also called Sheriff Wann, National Guard Commander Major Joe Starnes, and Court Reporter Hamlin Caldwell to testify as to the crowd outside.[22] However, they testified that the gathering of the crowd was "impelled by curiosity and not for hostile or punitive purposes".[21][23] Based on that testimony, Judge Hawkins agreed and found that the crowd in front of the court house was merely curious and not hostile.[24] The evidence Roddy adduced at that hearing, as recorded in the transcript, showed the existence of a mob atmosphere at the trials. That evidence became an important element in the reversal of these convictions by the United States Supreme Court. ==

Selection of the defendants for four separate trials

Judge Hawkins granted Moody and Roddy a recess of 25 minutes to consult with their clients, but no time to conduct an investigation of the facts of the case. Alabama law permitted jointly indicted defendants to demand separate trials.[25] However, neither attorney was given time to research the law before the Court would decide how the nine defendants would be joined or separated for trial. The prosecutor, H.G. Bailey, wanted to lead with his case against Charlie Weems, Clarence Norris, and Roy Wright. Victoria Price was their accuser and she was more certain than Ruby Bates as to the identity of her alleged attackers. Attorney Roddy objected that since Wright and Williams were not sixteen their cases should have been begun in juvenile court. As a result, the Court and the prosecution agreed that they would proceed against Weems and Norris first. The next trial would be against Haywood Patterson. The third trial would be against Olen Montgomery, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Eugene Williams, and Andy Wright. The last trial would be against twelve-year-old Roy Wright, since he was the youngest of the defendants. Each of these groups was then tried separately.[26]

Scottsboro trial of Norris and Weems

Judge Hawkins began the trials of Clarence Norris and Charlie Weems quickly. Moody and Roddy barely had time to figure out which of the nine defendants they were. Victoria Price was the first witness. A summary of her testimony, during direct and cross examination, was that she and Ruby Bates were riding with the white youths in the gondola car nearly filled with "chert", or gravel. A mile or two past Stevenson, Charlie Weems came into the car first, waving a .45 caliber pistol. Then, a crowd of eleven others followed into the car. Price testified that the "Negroes" began to fight with the white boys. She heard the black youths shout "unload, you white sons-of-bitches". They forced the white boys to jump from the fast moving freight train. However, Orvil Gilley, one of the white youths said he was afraid to jump because he was afraid he would be killed. So, the "Negroes" let him stay on board. Price continued that after the white youths were forced off the freight train and while the train was moving at high speed toward Paint Rock, the "Negroes", attacked them. Price testified that six of the black youths raped her and six of them raped Bates. She said Norris first demanded to know "if I was going to put out". Then he pulled off her coveralls and "step ins". She "struggled and hollered" while Weems held a knife to her throat and the others held her legs. She said three of the black youths who raped Bates had jumped off the train before it stopped at Paint Rock. The "Negroes" took turns holding her while others raped her. She testified that the leader, Weems, as the leader of the group, was the last to rape her.[27] That rape ended about five minutes before the train stopped at Paint Rock, where the posse captured the "Negroes". She said that she had snuff in her mouth and her attackers would not let her up to spit it out. One of her attackers had hit her in the head with the pistol. She testified, "When they got done with me they were still in there, telling us they were going to take us north and make us their women or kill us." She had fixed her clothes at Paint Rock and climbed out of the gondola car. She then fell unconscious and later came to in a grocery store. Two doctors had then examined her and she was taken to the Scottsboro Jail. During Attorney Roddy's cross-examination, Price livened her testimony with "wise cracks" that often brought a roar of laughter to the packed nearly all male, all white courtroom. She stated to Roddy that she was married, but she had not seen her husband in more than a month and did not know where her husband was at that time.[28] The Court sustained an objection to the defense question, "Were you ever in jail before?"[29]

Next was R.R. Bridges who testified that Virginia Price was talkative and "not hysterical" when he examined her. The only injuries he found were small bruises on her back and the top of her hips. There was no tearing in the area of her genitals. He found semen in her that was "non-motile", which meant that the spermatozoa in it were likely not living. The Court allowed him to testify, over defense objection, that it was "possible" that she had been forced to have sex with six men, one right after the other, and not have any more injury to her body than he found.[30][31] On cross examination, Dr. Bridges confirmed that Price had no lacerations and was not bloody. Bates had two small bruises, about the size of a "nickel" on both sides of her groin. He agreed that she also was not hysterical and showed no other injuries. The only semen he found in her was located in the area of her cervix. The defense asked, "Both of these girls admitted to you they had had sexual intercourse previous to this, didn't they?" The Court sustained the prosecution's objection to that question. The prosecution objected to defense questions about what the women had told the doctor about their sex habits, whether Ruby Bates had a venereal disease, or whether the women had previously been virgins. They asked "Both of them told you they had had sexual intercourse, one told you she had been married and the other told you she had been?", "From your examination could you tell whether or not they were subject to intercourse?"' "Were they virgins?", "That you find anything in the vagina that indicated to you these girls had had or might have had gonorrhea or syphilis?" And "other questions of like import." The Court sustained those objections.[30][32] Many later commentators hold the refusal of the Court to let the defense inquire into other ways the women might have ended up with that semen was another example of how the defendants were denied a fair trial. In fact, virtually every account of this case is quick to mention that the accusers were alleged prostitutes. However, it is interesting to note that this fact likely would not be admissible at the trial of their accused rapists even today under Alabama Code Section 12-21-203, the Alabama "Rape Shield Law." This law holds that the reputations for non-chastity or specific acts of non-chastity of the victims of an alleged rape are inadmissible. Dr. M.H. Lynch, the other examining physician, admitted on cross examination that the "girls were not hysterical" and there was "nothing to indicate any violence about the vagina."[33]

Posse member Tom Taylor Rousseau identified defendants Weems and Norris "as being among those taken from the train at Paint Rock from the gondola car." He testified that most or all of the defendants had gotten off the gondola car where the women had been riding and that Price had been carried off the train. He testified that he did not see the girls when they got off the train. However, he testified, "I saw Victoria Price a little later. When I saw her at that time, they were coming around the depot with her in a chair. She had her eyes closed and was lying over this way and they were bringing her from the depot up to town to the doctor's office. That was Victoria Price. I saw her later one time from where I was. She was still in the chair." This witness testified on cross-examination, among other things, that: "One of the girls was not in condition to walk. I did not help carry her off. There was an officer toted the girl up there. They toted her off the train, a fellow named M. A. Mize. He had to carry her away from the train, unconscious. I don't know about what the doctor said about her being unconscious at that time. I was not there. I was there at the time the girl was taken off." The Court sustained a prosecution objection to the question, "And if he [the doctor] testified immediately after their arrival here or at Paint Rock she was not unconscious, he is mistaken about it?"[32]

Jim Broadway testified as a State's witness. He testified that he was present at Paint Rock when Victoria Price and Ruby Bates left the train. He said, "I saw Victoria Price there. We got her off the freight train. She was on one of these gravel cars. That is known as a gondola car. There was another woman with her, the Bates girl. The Bates girl seemed to be in fairly good shape, but the other could not hardly talk and couldn't walk." The Prosecutor asked him, "Did you hear them make any complaint there, either one of these girls, of the treatment they had received at the hands of these negroes?" Defense counsel "severally objected to this question on the ground that it called for incompetent, irrelevant, immaterial, and illegal testimony, and for hearsay testimony." The court ruled that the answer be limited to Victoria Price, the person named in the indictment as the victim, and the defendants again objected on the same ground. The objection being overruled, the witness was actually of some help to the defense when he answered, "I did not hear Victoria Price make any complaint, either to me or anybody else there, about the treatment she had received at the hands of these defendants over there. We sent and got a chair for Victoria Price and carried her to the doctor's office at Paint Rock."[34]

Ruby Bates was the next witness, who testified over strong defense objection. She only testified on direct examination that the defendants had entered the railway car in which she and Price had been riding, where they proceeded to throw the white youths off the train. She said nothing about either of them being raped. It is a principle of cross examination that attorneys do not ask questions unless they know the answers. On cross examination, the defense elicited from Bates that she had been "ravished" by "six negroes".[note 3] One held a knife to her throat, while another pointed a gun at her and while yet a third raped her. She said she had never been married. The Court sustained a defense question as to whether she had previously had sexual intercourse.[34]

The prosecution ended with the testimony of three men from Stevenson. Luther Morris testified that he had seen between eight and ten blacks "put off" five white boys from the train and "take charge of two girls". The blacks had stopped the girls from jumping off the train and had pulled them back on. T.L. Dobbins testified that he had seen "three darkies in a boxcar" and several more fighting in the gondola car. The last prosecution witness, Lee Adams testified that he had seen a group of blacks "striking" the white boys in the gondola car. Later, he saw them walking toward Stevenson with blood on them. The prosecution rested without calling as its witness any of the white youths who had been put off the train.[35]

The first defense witness was defendant Charles Weems. He testified that he was not part of the fight that broke out between the black and white youths on the train. He said that the Haywood Patterson was the person with the pistol and that he had not known him before that time. Patterson had threatened to shoot him, if he did not help force the white youths from the train. He said he did not participate in the fight, but had merely asked the white youths to get off the train. He said the first time he saw the white girls is when the train pulled into Paint Rock. On cross examination, Charles Weems stated that it was Clarence Norris, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson and Olen who were in the gondola car with Haywood Patterson and him.[36] Charles Weems testified on cross examination, "We were all in the gondola when we got to Paint Rock. I never saw no girls in this gondola we were in at all. I first saw the girls when they came toting them through Paint Rock. They had the oldest girl in a chair coming through Paint Rock. She did not get out of the gondola I got out of. I don't know whether she got out of a gondola or not. The first I saw of either one of the girls they were bringing the oldest girl up in a chair."

Defendant Clarence Norris was the next defense witness. He stunned everyone by implicating all the others. On direct examination, he denied that he had participated in the fight or even had been in the gondola car where the fight took place. However, he unexpectedly volunteered that he had seen what went on in the gondola car. He testified that Haywood Patterson stated his intention to force the white boys off the train and that "he was going to have something to do with them white girls". On cross-examination, things got worse. He testified "I did not get into that gondola at all. I just looked in. This Weems I was speaking about here is not my friend. I knew him. I saw him over in the gondola and I saw the girls in there, but I did not go in there. I saw that negro in there with those girls. I seen everyone of them have something to do with those girls after they put the white boys off the train. After they put the white boys off I was sitting up on the boxcar and I saw every one have something to do with those girls. I was sitting on top of the boxcar. I saw that negro just on the stand, Weems, rape one of those girls. I saw that myself. When the officers searched me they did not find anything on me. They did not find a pearl handled knife. They did not find a pearl handled knife on me. I did not have a knife or pistol. I did not go down in the car and I did not have my hands on the girls at all, but I saw that one rape her. They all raped her, every one of them. There wasn't any one holding the girls legs when Weems raped her, as far as I saw. The other boy sitting yonder had a knife around her throat, that one sitting on the end behind the little boy. I don't know what his name is, but he is the one that had the knife. I did not see the little one hold of her legs while this one was raping her. I did not see anybody holding her legs. I don't know who pulled off her overalls. The girls were lying down when I got up on the boxcar. This big one did not have a knife on her throat. That little boy sitting behind yonder I don't know his name is the one that had a knife around her neck, making her lie down while the others raped her. I didn't see any of the negroes take her overalls off. The girls were lying down when I got up on the boxcar. I saw the overalls lying in the car. I did not see any step ins. I did not get down in the gondola, never did get down in there."[34][37] The defense put on no further witnesses.

After some brief rebuttal testimony, the prosecution argued to the jury that it was most horrible crime in the history of the state. "If you don't give these men death sentences, the electric chair might as well be abolished."[38] Likely stunned into silence by Norris' damning testimony, the defense made no closing argument at all. They did not even argue against the death penalty for their clients.[38] The Court started the next case against Haywood Patterson, while the jury was still deliberating that one. The first jury deliberated less than two hours before returning a guilty verdict in that case and imposing the death sentence on both Weems and Norris.[39]

When the guilty verdicts were announced, the courtroom erupted in cheers and some of the celebrating crowd poured out into the street in front of the courthouse. Judge Hawkins' heavy gavel pounding did not restore order in the courtroom. He ended up ordering the national guardsmen to restore order, who ended up throwing eight of the shouting spectators out of the courthouse. When word of the guilty verdicts reached the crowd outside, another roar of celebration went up. The band, supplied for the occasion by the Ford Motor Company for a show of its cars outside, struck up Hail, Hail the Gang's All Here and There'll be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.[39][40]

Scottsboro trial of Patterson

The trial for Haywood Patterson began almost immediately after the cases of Clarence Norris and Charlie Weems had gone to the jury and while the jury was briefly considering the fate of the first two youths. The lead witness at the Patterson trial was again Victoria Price. This time she testified that Patterson was one of the twelve black youths who had poured into the gondola car in which she and Ruby Bates had been riding, right after the train left Stevenson. They ordered the white youth off the train and Patterson shot one of the white youths with a .38 caliber pistol while the blacks were doing so. While the other black youths held her down, Patterson raped her. On cross examination, the defense elicited the damaging testimony from her that she fought as hard as she could, as three of the defendants ripped off her clothing and three of them raped her and six other black youths raped Ruby Bates. The defense asked her if she had "ever practice[d] prostitution." Judge Hawkins sustained a prosecution objection to the question. However, Price volunteered afterward that "I do not know what prostitution means. I have not made it a practice to have intercourse with other men." The defense countered, "Never did?" Again, the prosecution successfully objected to the question and again Price volunteered anyway that "I have not had intercourse with any other white man but my husband. I want you to know that."[39][40]

Right after the testimony of Ruby Bates, the Haywood Patterson jury was moved to a room only about twenty feet away while the first verdicts were announced, where they were within clear earshot of the uproar that broke out upon the announcement of the convictions of Norris and Weems.[citation needed] When order was restored, the Patterson trial resumed. Attorney Roddy made a motion for a mistrial of Patterson's case, due to what the Patterson jury had obviously just heard. Judge Hawkins denied this motion.[41]

Dr. R. R. Bridges was the only physician the prosecution offered at the trial of Haywood Patterson. He testified, "I found their vaginas were loaded with male semen, and the young girl was probably a little more used than the other, the other not showing as much. On the body were bruises on the lower part of the groin on each side of Ruby Bates, that is the young one, and there was a bruised spot around the hips, or the lower part of the back, on the other girl, the Price girl, a few scratches, small scratches on the hands and arms, and a blue spot here (indicating) on the neck of one of them. I think that was Mrs. Price, I will not be sure about that."[40]

Posse member Tom Taylor Rousseau testified that "the negroes" had gotten out of the same gondola car as Price and Bates. C. M. Latham agreed with that fact and added that the women had said "We have been mistreated" as they climbed off the gondola car. Lee Adams testified that he saw the fight between the black and white youths on the train and that, shortly thereafter, he had seen the white youths hurrying back toward Stephenson. Farmer Ory Dobbins, who had not testified at the first trial, said, from his farm along the rail line, he had seen white women in the company of black youths, and he had seen one of the "colored men" grab a white woman and throw her down.[42]

Haywood Patterson testified on his own behalf as the first defense witness. He said on direct examination that he had seen Price and Bates in the gondola car, but had nothing to do with them. On cross-examination he testified that he had seen "all but three of those negroes ravish that girl." However, then he said had had not touched those girls or even seen "any negroes on top of either of those girls." In fact, he had not even seen "any white women" until the train "got to Paint Rock."[43] The prosecutor asked him, without defense objection, whether he had heard co-defendant Norris accuse him of the rape in the previous trial. He admitted that he had, but denied the accusation.[44]

The defense offered thirteen-year-old co-defendant Roy Wright as a witness. He testified on direct examination that "That boy [defendant] did not have anything to do with those girls on that train. He was not down in the car with those girls; he was standing up on top of a boxcar. I saw a pistol. A long, tall, black fellow with duck overalls on; that is the only pistol I saw. This boy [defendant] did not have a knife. He did not open his mouth to the girls. I saw the girls on the train. They were on an oil car when I saw them. There were nine negroes down there with the girls and all had intercourse with them. I saw all of them have intercourse with them. I saw all of them have intercourse; I saw that with my own eyes. The defendant was not down there; he was never down there with the girls. The boys I left Chattanooga with were named Haywood Patterson, Eugene Williams, and Andy Wright."[40] On cross examination, Roy Wright testified that "The long, tall, black fellow had the pistol. He is not here. I saw none of those here with a pistol. I saw five of these men here rape the girl. After we put the men off, we went back on the boxcar and I was sitting up on the boxcar holding to that wheel, looking down at them. I did not tell the officers I saw everyone rape her but me. I did not tell them that. I did not tell them that I saw the defendant rape her. I did not see the defendant rape the Bates girl. I did not see him do anything except he just helped put off the men. He was putting them off because they kept stepping across him and talking about putting us off. I saw one knife down in there. That boy back there [indicating] had it, Eugene; he is the one that had the knife. I did not see him hold it on the throat of that girl. He did not have hold of her throat, because he was sitting up on the boxcar. I saw one down in the gondola, a little white-handle knife. Clarence Norris had that knife; I do not know where he got it; I do not know what he did with it. He had it the last time I know anything about it. I am sure the defendant did not do anything."[45]

Co-defendants Andy Wright, Eugene Williams, and Ozie Powell all testified that they did not see any women on the train. Olen Montgomery testified that he sat alone on the train and did not even know any of it had happened at all.[46]

The testimony over, the case of Haywood Patterson went to the jury. It convicted him and sentenced him to death after two hours of deliberation.[47] However, this time Judge Hawkins made sure there was not another outburst as had occurred when the first verdict had been announced. "If I hear pin drop" he warned the court room, "the persons guilty will be sent to jail."[48] There were twenty-five guardsmen in the courtroom to back Judge Hawkin's words. The Patterson guilty verdict and death sentence by electrocution were delivered to a dead silent court room.[48]

Scottsboro trial of Powell, Williams, Roberson, Montgomery and Andy Wright

The trials of Ozie Powell, Eugene Williams, Willie Roberson, Olen Montgomery, and Andy Wright began within minutes of when the jury began deliberating the case against Haywood Patterson. This third jury was sent out briefly while Haywood Patterson's second jury filed in to pronounce its guilty verdict against him.[49]

Victoria Price again took the stand to testify that every one of the defendants now on trial had been among the twelve black youths who had come over the roof of the adjoining boxcar to pour into the gondola car where she, Bates, and the white youths were riding. After they threw all the white boys off the train except young Gilley, they split into two groups of six to rape each of them. She pointed to Eugene Williams as the one who held the knife to her throat. Then, she pointed to Olen Montgomery and accused, the "one sitting there with the sleepy eyes. He ravished me, while the others urged him to hurry because they wanted their share." While another of them held her legs, "the others were going up by the side of the car, looking and keeping the white boys off, telling them that they would kill them, that it was their car and we were their women from then on." She accused every one of them of having knives and said every one of them was still in the gondola car when the train arrived in Paint Rock. She repeated that she had lost consciousness after getting off the train and that she was taken to Scottsboro where the two doctors had examined her.[50] The cross examination of Price allowed her to elaborate on how it took all three of the defendants to pull off her overalls. On redirect by prosecutor Bailey, she testified that Eugene Williams, Olen Montgomery, and Andy Wright had all raped her. She testified, "While one was having intercourse with me, the others were running up and down the car box hollering, 'Pour it to her, pour it to her'."[48] While this was going on, she said, others were holding a knife to the throat of the white boy, Gilley.[48]

The trial was interrupted for the return of the guilty verdict for Haywood Patterson, which this time had not resulted in an uproar. However, as soon as that verdict was rendered and that jury discharged, this trial immediately resumed.

The next witness was Ruby Bates. She identified defendants Ozie Powell, Eugene Williams, Willie Roberson, Olen Montgomery, and Andy Wright as being among the twelve who had poured into the gondola car to force the white youths in it to unload. Cross-examination again helped mostly the prosecution. She added that a "colored boy" had pulled off her overalls and six of them had "ravished" her and Price by others. However, unlike Price, she could not identify her alleged rapists.[48]

Dr. R.R. Bridges was the next prosecution witness. He repeated his earlier testimony about examining the women and the minor scratches and bruises he found on them. He stated that both had engaged in sexual intercourse, but he could not say when. He testified that each had semen in them, with Price having much more than Bates. Their vaginas were "still loaded with secretions, and especially in the Bates girl; her vagina had more secretions than Mrs.[sic] Bates; both had plenty of semen in there, plenty of male germ. In my judgment as a physician, six negroes could have gone to these women without lacerating them or tearing their genital organs."[51] On cross examination, the defense elicited from him on cross that he detected no movement in the spermatozoa from either woman he examined with his microscope, of he could not say whether they were "dead or alive." Dr. Bridges admitted that he had examined, defendant, Willie Roberson and "He is diseased with syphilis and gonorrhea, a bad case of it. He is very sore. It would be painful [for him to have sex], but not very painful. It is possible for him to have intercourse. I have seen them that had it worse he has."[51] The defense got him to repeat that neither woman had any genital lacerations. Then, they got him to admit that Victoria Price told him that she had had sex with her husband and "the other [Ruby Bates] said she had" earlier engaged in sexual intercourse as well.[51]

The prosecution put on two witnesses who testified that the five defendants were in the same gondola car as the women when the train arrived in Paint Rock. It finished its case with two witnesses who testified they saw an altercation on the train right after it pulled out of Stevenson that day.[51]

The defense proceeded with the only witnesses they had time to find — the defendants. Ozie Powell admitted that he had seen the fight, but he said he was not in the gondola car and had not participated in the fight and had not even seen the women until the train arrived in Paint Rock. Willie Roberson next testified that he was riding in a boxcar at the back of the train, where he had seen neither the fight nor the women. Willie Roberson testified further that he was suffering from a bad case of venereal disease. He stated that it would have been impossibly painful for him to commit a rape. He testified, "I have chancres. It pains and hurts me all the time. I was sick on the boxcar. There was something the matter with my privates down there. It was sore and swelled up. It hurt me to walk. I cannot lift anything. I am not able to have sexual intercourse. I couldn't have."[51] Andy Wright testified that he had seen the fighting between the "colored and whites", but said his only role was to pull Gilley back on the train to keep him from getting hurt. He insisted that he had not even seen the women on the train and only found out they were there when the train got to Paint Rock. He had been by himself in a boxcar near the rear of the train and had not seen what happened to the white women. On cross-examination, he denied having raped the women. He denied that he said at the time, "Yes, you will have a baby after this." The emphasized, "I will stand on a stack of bibles and say it." Olen Montgomery testified that he had been in a boxcar near the end of the train and had seen and done nothing. He testified, "If I had seen them, I would not have known whether they were men or women. I cannot see good. His glasses were not good and he had lost them after his arrest. Eugene Williams also denied participating in the fight in the gondola car, but admitted he had seen it. However, he also denied having seen the women. On cross examination he admitted that he had been carrying a knife, but he denied that he has used it to help rape the women.[51]

The prosecution called Victoria Price as a rebuttal witness. She repeated her claim that Eugene Williams had raped her, while the others held William's knife against her throat. The prosecution then called witnesses who testified that they saw Willie Roberson run over train cars and leap to the next cars to show that he was not in as bad a physical shape as he said his venereal disease had rendered him.[51]

The prosecution called Sim Gilley as a rebuttal witness, the white boy who Price had testified was in the Gondola car at the time of the rapes. He testified that he "was one of the boys on the train that day" and that he saw all the "negroes" in that gondola. The prosecution asked him, pointing to the defendants on trial at the counsel table, "How many in that row there? Look at that row of five sitting on the front — get up and walk over there if you cannot see them." The defense vigorously objected to this testimony on the ground that the state was "reopening the case". That is, the state was presenting entirely new evidence and was not "rebutting" (that is, responding to) any evidence the defense had offered in its part of the case. The Court overruled the objection. Gilley then testified that he saw "every one of those five in the gondola."[52] However, he did not confirm that he had seen the women raped, and, probably with good cause suspecting a prosecution trap, the defense just left it that way by not asking him any questions about it.

The defense again waived closing argument. The prosecution, knowing from the previous trials that the defense would do this, stood up, went to the jury and proceeded to make more argument. The defense objected vigorously, but the Court allowed it.[52] Judge Hawkins instructed the jury that any of the defendants who aided and abetted the crime were just as guilty as any of the defendants who had committed it. The jury began deliberating at four in the afternoon on Wednesday, April 8, 1931. Early Thursday morning, the jury found them all guilty and imposed the death penalty on all of them.

Scottsboro trial of Roy Wright

The prosecution agreed that 14-year-old Roy Wright was too young for the death penalty and agreed not to seek it against him. The prosecution presented only the rehashed testimony of Price and Bates against him. The defense presented only the testimony of Roy Wright himself. His case went to his jury at nine that evening, which had both juries deliberating at the same time. The guilty verdicts and death penalties were returned against Powell, Williams, Roberson, Montgomery, and Andy Wright came at nine on Thursday morning but Roy Wright's jury hung that afternoon. All the jurors agreed on his guilt, but seven insisted on the death sentence and five held out for life imprisonment, even though the prosecution had not requested it. Judge Hawkins declared a mistrial for Roy Wright.[53]

The eight death sentences

The eight convicted defendants were assembled together on April 9, 1931 to be sentenced by the Court to death by electrocution, the first time Judge Hawkins had pronounced the death sentence in his five years on the bench. The Associated Press reported that the defendants were "calm" and "stoic", as Judge Hawkins handed down the death sentences one after another.[53]

Judge Hawkins fixed their executions for July 10, 1931, which was the earliest date Alabama law allowed. The defendants were immediately sent to death row in Kilby Prison in Montgomery, Alabama. Their cells were next to the execution chamber. While appeals were filed for them, the Alabama Supreme Court issued indefinite stays of executions for them only seventy-two hours before they were scheduled to die. During their wait on death row, another prisoner, Will Stokes, was executed on July 10, 1931, which they could hear. They later recalled that Stokes had "died hard".[54]

The Communist Party takes over the cases

The calling out of the National Guard attracted the attention of the national media to small town Scottsboro and its trial. The New York Times and the Associated Press reported the trial, which caused a demonstration in Harlem. The cause of the Scottsboro defendants had also come to the attention of the American Communist Party. James Allen, who was a party member, Chattanooga resident and editor of the Communist publication Southern Worker, first heard about the case over Chattanooga radio right after the posse stopped the train in nearby Jackson County, Alabama. The Party took a quick interest in the case. "By publicizing the plight of the boys and defending them in court, the Party saw the chance to educate, add to its ranks, and encourage the mass protests not only to free the boys but bring about revolution."[55] As a result, the Communist Party used its legal arm, the International Labor Defense (ILD), to take up their cases within a week after the guilty verdicts.[56] The ILD persuaded the parents of the defendants to let them champion their cause. The ILD and the parents together then retained attorney Joseph Brodsky and former Solicitor General of Hamilton County, Tennessee, George W. Chamlee to represent them on appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court. The NAACP tried to persuade them to let them handle the case, offering even the services of famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow. However, in the end, the Scottsboro defendants decided to let the ILD handle their appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court.[citation needed]

Motions for new trial

Newly hired attorney George W. Chamlee moved for new trials for all defendants. Private investigations took place, and revealed that Price and Bates had been prostitutes in Tennessee. In fact, acquaintances alleged that Price had regularly serviced both a black and white clientele in the mixed race neighborhood in which she had plied her trade.[57] Chamlee offered Judge Hawkins affidavits to that effect, which Judge Hawkins forbade him to read out loud. The defense argued that this information proved that the two women had likely lied at trial both about not being prostitutes and not having had sex with men other than the defendants.[58] Chamlee also made it part of the basis for the motion for new trial the demonstration after the trial as further evidence that the initial petition for a change of venue based on a hostile community attitude toward the defendants should have been granted. Retrial attorney Samuel Leibowitz is almost universally credited with raising the issue of the fact that African Americans were excluded from Alabama juries. However, his role in raising the issue on retrial was to put on actual witness testimony on the issue, which thereby got into the record of the case the undisputed facts that eventually allowed the defendants to prevail on the issue in the United States Supreme Court. It was Chamlee who first raised the race exclusion issue in the case when he made it part of his motion for a new trial.[59] Judge Hawkins quickly denied these motions, but they became the basis upon which the new defense team unsuccessfully tried to get these issues before the Alabama Supreme Court, in the place of the objections at trial that attorneys Moody and Roddy had failed to make.[note 4]

Alabama supreme court affirms convictions

The convictions were all duly appealed to the Alabama Supreme Court, which affirmed all but one of them.

Following Judge Hawkins's denial of the motions for new trial, Communist Party hired Attorney George W. Chamlee filed an appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court, where he moved for and received the routinely granted stay of execution for his clients. Chamlee was joined in this appeal by Communist Party hired attorney Joseph Brodsky and ILD attorney Irving Schwab.

One of the main arguments of the NAACP in trying to persuade the defendants and their families to let them handle the case was that the involvement of the Communist Party would cause a backlash against them — which it did. When Brodsky and Chamlee presented their oral argument to the Alabama Supreme Court, they received a very frosty reception. The justices accused the ILD of being behind the threats they had been receiving, which Brodsky and Chamlee emphatically denied. Brodsky and Chamlee still stoutly made several pointed arguments to the Court. They argued that their clients had not had adequate representation from their unable to prepare attorneys. They argued, because of the short time span between arrest and trial, there had been no opportunity for their clients' trial counsel to prepare their cases for trial. They argued the crowd had intimidated the jury. They argued that it was unconstitutional to exclude blacks from the jury that had convicted their clients. Alabama Attorney General Thomas Knight, Jr. and son of one of the Justices, Thomas Knight, Sr. to whom he was arguing (who did not recuse himself), had little need to say much. He made the argument that the crowd in Scottsboro was completely understandable, because of the natural passion of Southerners to defend white womanhood. Whether or not what Attorney General Knight argued about white Southerners was factually true, that fact was not in the record of the case and there was, of course, no justification in the law for a mob to intimidate a jury — then or now.

Appeals courts seldom reverse a case because there was not enough evidence presented at trial to convict the appellant before them. There either has to be no evidence at all of guilt in the record or that "reasonable minds cannot disagree" that the facts found by the jury were impossible — like if a rape victim positively identifies a defendant, while the DNA results positively show it could not possibly have been he, but the jury convicts him anyway. Otherwise, the offsetting maxim in the law to guide appellate review is that "reasonable minds differ." Therefore, if appellate courts find any evidence at all in the record that, "if believed," supports a finding of guilt, they will not reverse a conviction because there is merely a weak case against the appellant before them. Thus, when Victoria Price and Ruby Bates testified that they had been raped and identified these defendants, these condemned youth no longer had any chance of getting an appeals court to agree that there was not enough evidence to sustain their convictions. If the jury believed them, then no appeals court reviewing the case will ever question the soundness of that belief. With that principal in mind, the Alabama Supreme Court's opinions paraded much of the evidence against these appellants that, "if believed", would support the convictions against them. However, the Court's opinions made many gratuitous expressions of outrage about the horror of the crime before them, which left little doubt that they believed it all "in whole cloth". So, the only real question before the Alabama Supreme Court on these appeals was whether the trial court made procedural errors — that is, errors in the way Judge Hawkins conducted the trial. Even arguing that the trial judge made a procedural error is an "uphill battle" for appellants. All appellate judges may review are the passionless words in the trial transcript. Trial judges, on the other hand, were there live and are thought to have the best feel for how the case should be conducted. The law thereby gives them considerable "discretion" in how to manage the actual conduct of the case. As a result, what appellant courts review is whether the trial judges in question "abused their discretion" — a very murky principle which is basically what the appeals court says it is.[note 5] Far away in place and time, appeals courts, more often than not, are slow to second guess the "front line" trial judge and find such abuse. So, time after time, the Alabama Supreme Court found that, while they did not put it this way, the many things Judge Hawkins did in the trial of these cases that made it impossible for these appellants to defend themselves was within his "discretion". Another principle of appellate review is that defendants must object to an alleged "error" at trial before that alleged error will be reviewed on appeal. Referring to that principle, time after time, the Alabama Supreme Court refused to consider the most egregious instances of judicial abuse in the cases before them, because frantically rushed Attorneys Moody and Roddy had not objected to them before or during trial. The appellants' new legal team had raised those issues only after the trials in their motions for new trial.

Decision for Patterson

On March 24, 1932, the Alabama Supreme Court issued its decisions on these appeals, in which Justice Joel Bascomit Brown, writing for the majority, confirmed the convictions and death sentences of all but juvenile thirteen-year-old Eugene Williams. These cases were not published in the order they were tried, which enabled the Court to refer to cases in its later decisions rather than repeat all of its rationale in all of its decisions for these highly interrelated cases.

The first appeal the court considered was that of second to be tried Haywood Patterson. The Court first considered his assertion that the petition for a change of venue should have been granted. However, the Court noted that he had signed it himself at a point he was confined in jail and thereby could not possibly have known the "state of the general public feeling and sentiment of the county". Roddy and Moody had attached three newspaper articles to their petition reporting the crowd that had gathered for the trial. However, the Court did not see anything particularly "inflammatory" in them. "In fact," the Court ruled, "these publications were in a sense conciliatory, apparently designed to suppress rather than create an unlawful hostile sentiment against the accused." As to "the articles appearing in the Montgomery Advertiser and the Chattanooga paper, there was no evidence showing to what extent, if any, said papers were circulated in the county from which the jurors were to be drawn, and in the absence of such proof these publications were entitled to little or no weight."[60] The Court noted that the only testimony from witnesses "who were in a position to ascertain and know the nature of the public feeling", offered to support the hostility of the crowd was from Sheriff Wann and National Guard Commander, Major Starnes. They testified that "the crowds that gathered were not disorderly, and readily dispersed when advised by some of the leading citizens of Scottsboro to do so, and there is nothing in the evidence going to show race prejudice against the accused, or local prejudice in favor of the girls who are alleged to have been mistreated. In fact, neither the defendant nor his alleged victims reside in Jackson County."[60] Thus, as to the crowd outside the court house, the Court found, "the evidence shows nothing more than the gathering of a crowd impelled by curiosity, and not for hostile or punitive purposes."[60] The Court conceded, "True, the evidence shows that the sheriff requested the Governor to send a company of the state militia to protect the defendant, and that prompt orders to this end were given and carried out, and that they were present during the proceedings; but this, without more, is not enough to authorize the granting of the motion."[60] So, the Court found no error in the denial of the Petition for a Change of Venue.

The appellants cited as error that they had not been allowed at trial to ask Victoria Price, "Did you ever practice prostitution?" The Court ruled that not allowing this question was proper because her consent was not an issue in the trial. Moreover, the Court ruled, "Previous chastity is not an essential element of the offense charged in the indictment, and, where this is so, rape may be committed on an unchaste woman, or even a common prostitute."[60] The Court ruled that the question to the examining doctor as to whether the women had a venereal disease was properly denied for the same reason.

The new defense team, in their motion for a new trial, had asserted that there was no evidence that Patterson had participated in the rapes and therefore Judge Hawkins should have granted him a new trial. However, the Court noted that Petterson's own witnesses had "participated in the affray with the white boys." From this testimony, the Court concluded that "This testimony tends to show a conspiracy between those who went into the car and forced the white boys from the train, and that this appellant aided and abetted in the commission of the offense."[60] Thus, "the verdict is amply supported by the evidence."[60]

The motion for new trial asserted as prejudicial that the crowd in the previous case has burst out in applause within the hearing of this appellant's jury. The Court noted that there was no mention of that in the record of the case. While the appellant had offered affidavits and testimony to the effect that this outbreak of applause had occurred, the Court ruled, "It is not permissible to inject such matters—occurrences during the trial in the presence of the court—by evidence aliunde on the hearing of the motion for a new trial, for the all-sufficient reason that such practice would inject into such hearing a controversy in respect to which the court might be advised by his own personal observation, leading to the conclusion that the issue was without merit."[60] In other words, it was not possible to prove with testimony what the trial judge had been in a position to observe personally. If the trial judge did not mention it, nothing had occurred. Therefore, the Court concluded, "the issue is not presented."[60] The Court found no error.

The appellant raised in its motion for new trial the prejudicial effect on this appellant's jury of the uproar on the street and the band striking up when the first guilty verdict was announced. The Court described this outburst as "some commotion on the streets". As to the band playing such tunes as There'll Be A Hot Time In The Old Town Tonight, the Court found that, "the parade was put on by the Ford Motor Company in demonstrating Ford trucks, and had no connection with the proceedings in this case against the defendant; that the noise was made by a graphophone with an amplifier to attract the people in Scottsboro to inspect the caravan of Ford trucks, brought into Scottsboro by the 'Ford people' in no way connected with that county, except they had an agency there. The only other music was by the hosiery mill band playing for the guard mount of the militia after 6 o'clock in the evening."[60] Anyway, the Court continued, "The evidence as to the extent of the commotion or applause in the street was in conflict, and the evidence fails to show that it was such as to reach the ears of the jury, which was then confined in the jury room in the courthouse."[60] Again, the Court found no error.

The appellant raised in his motion for new trial that Negroes had been excluded from the jury that tried him. However, the Court noted that the issue had not been raised before trial and found that there was no support for this allegation, if it had. It ruled, "there is nothing in the statutes regulating the selection of persons qualified to serve as jurors, or in the interpretation of said statutes by the courts that in any way discriminates against any citizen as to his right to serve as a juror; nor does the evidence show any such discrimination in this case."[60] So, denying a motion for new trial on this ground also was not error.

Last, the Court addressed the appellant's assertion of "newly discovered evidence" in the form of the affidavit that accuser Victoria Price was a "common prostitute". The Court said that this new evidence did not go to prove that the appellant had not had sexual intercourse with Price. It did not support his contention that he was not in the gondola car when the rape occurred. Further, "evidence going to show specific acts of sexual intercourse between the alleged victim and other men, and her general reputation for chastity, was not material as going to show consent."[60] Anyway, this evidence went only to Price's credibility, which was not the sort of evidence that warranted a new trial.

Therefore, the Court affirmed the conviction of Haywood Petterson as well as his death sentence.

Decisions for Powell, Williams, Roberson, Montgomery and Andy Wright

The Alabama Supreme Court did grant thirteen year old Eugene Williams a new trial because he was a juvenile. The Court addressed the issue raised by Williams that he was under the age of sixteen at the time of his trial and that the Circuit Court in Scottsboro, as a court for adults, had no jurisdiction over him. The Court ruled that it was not up to him to prove that he was a juvenile. Instead, when it was "suggested" to the court that he was a juvenile, the burden was on the prosecution to show that he was not. The Court agreed that Moody and Roddy had brought his age to the attention of the trial court before his trial. Further, affidavits had been filed in the case as to his date of birth and the state had presented no evidence to contradict that evidence. The Court ruled, “Since the statute declares a juvenile delinquent to become a ward of the state, it became the duty of the trial court, upon suggestion that the defendant Eugene Williams was under sixteen year of age, or if his personal appearance suggested a doubt as to his age, to ascertain his age, and, if found to be under sixteen years old, to transfer the case . . . to the probate court, as the juvenile court.” [61] Thus, Williams became the next of the Scottsboro Boys, after Roy Wright, to escape death. However, the Alabama Supreme Court did leave open that possibility, noting that, if the juvenile court found that “such delinquent cannot be made to lead a correct life and cannot be disciplined”, the probate court had the power to send him back to circuit court to be tried again as an adult.[62]

The appellants had cited as error that the indictment against them was unconstitutionally vague. The Court reviewed the law on what constitutes a valid indictment in Alabama and found that the indictment against the appellants fully complied with that standard and was therefore valid. The appellants had cited as error how the jury was selected for their case. The Court reviewed the law on what specifies how juries are selected in Alabama and found that the process by which the jury that had tried the appellants had fully complied with that standard and their jury therefore had been properly selected. The appellants had cited as error the way they had been joined for trial. The Court noted that how cases were joined was within the "sound discretion" of the trial court and, more, that Roddy and Moody had not objected to how the appellants' cases had been joint — which they had not. Therefore, none of these purported errors was "reversible error".[63]

The Court next considered whether Judge Hawkins's denial the petition of Roddy and Moody for a change of venue, which they made right before the start of the first trial, was an "abuse of discretion". The Court did not see the crowd as "threatening." It recited that "the petition does not charge that any actual violence, or threatened violence was offered the prisoners or any of them. Nor does it appear that the 'hundreds of people who gathered about the jail' were armed or disorderly in any wise or to any extent.[64] As to the inflammatory newspaper coverage of the trial, the Court observed that newspapers "have the right to keep the public informed of the happenings throughout the country. Such is the sphere and scope of their enterprise." Therefore, it is only to be expected that they would report this particular crime. Further, "Newspaper accounts, of themselves, cannot be made the sole basis for a change of venue. It must be made to appear to the judicial mind that these accounts, by their circulation, so molded and fixed public opinion as to make it proper that the cause should be removed to some other locality not so affected for trial.".[65] But, no matter what, "Most people of fair judgment, are honest in their convictions, where life and death are at stake, until after due consideration of the facts of the case. And may we also add that, under the laws of Alabama, only such classes are permitted in the jury box."[65] The Court held that the presence of the National Guard at the trial had assured that those trials had been lawfully conducted. They quoted the testimony of National Guard Commander, Major Starnes, who testified at the change of venue hearing that "I have not heard any threats made against these defendants. . . . I think these defendants can obtain here a fair and impartial trial and unbiased. . . . I have seen a good deal of curiosity but no hostile demonstration."[65] The Court continued that if was only natural that "where womanhood is revered and the sanctity of their persons is respected," that "many should have been attracted to Scottsboro during the days covered by the trial, and the preliminaries incident thereto is no small wonder, considering the character of the crime charged against the defendants."[66] The burden was on the defendants to show that a change of venue should have been granted and none of what they had presented was enough to do that. "The evidence fails to show that their trial was dominated by a mob or mob spirit, or that there was at any time any mob present at, or during, the trial, or that the jury was inflamed against the defendants to the point where the defendants to the point where they could not get or did not give the defendants a fair and impartial trial; nor does the evidence show that there was any violence, actual or threatened, against the defendants, from the time of their arrest to the conclusion of their trial."[66] To the twenty first century eye, this part of the Court's opinion may seem, to borrow the colorful phrase of eighteenth century British philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, "nonsense on stilts." It, of course, did not advance the cause of these black appellants in 1932 Alabama that they stood convicted of raping white women-–a crime much worse than merely murdering them. James Goodman, Stories of Scottsboro, p. 220. However, some of these unprepared, illiterate and terrified defendants had essentially testified on the stand, and thereby in the court records that this Court was reviewing, that the rapes had indeed occurred by saying they saw some of their co-defendants committing them. Courts going through many legal gymnastics to keep "obviously guilty" (as they see it) criminal defendants from "getting off on a technicality" is not completely unheard of today, in cases where race obviously played no role at all.</ref>

The Court next reviewed the defense objection to the calling of Sim Gilley (the white boy who had not been thrown off the train) as a "rebuttal witness", after the defense had closed its case, when he did not "rebut" any testimony that the defense put on. He had testified that he had seen all the defendants in the gondola car where the rapes allegedly had taken place. However, the Court ruled that the "evidence was strictly admissible. Whether it was rebuttal, strictly speaking, we cannot affirm, but, if not, the propriety of admitting it was addressed to the sound discretion of the court. There was no error in this ruling of the court."[67] The Court made quick work of the defense objection to Judge Hawkins letting the prosecution make a second argument to the jury after the defense had waived its closing argument. It just ruled that Judge Hawkins "clearly" had the discretion to allow that.[67]

The new defense team asserted that the demonstration that had broken out in the court room upon the return of the first guilty verdict had prejudiced the trial of these defendants. However, the Court held that the testimony presented at the hearing on this motion for new trial did not support that there was any such prejudice caused by these "alleged demonstrations". The Court based this finding on the testimony of several of the jurors for this case, who testified at that hearing. More importantly, the Court held, the defense did not object to this applause and the trial court handled it properly.[67][68]

In response to the defense motion for new trial on the ground that there had not been enough time to prepare for trial, the Court responded, "No motion for a continuance appears in the record. Therefore, this contention cannot avail defendants made for the first time after verdict. Application, made upon proper grounds, should have been made to the court before the trial was entered upon."[69] As to the Judge Hawkins's immediate trials, the trials had merely granted those defendants their constitutional right to a speedy trial. It observed, "If there was more speed and less delay in the administration of the criminal laws of the land, life and property would be infinitely safer and greater respect would the criminally inclined have for the law."[70]

The appellants cited as error that Judge Hawkins had not granted their motion for new trial on the ground that Negroes had been excluded from the jury. The Court refused to consider that issue, since the defense had not raised it before trial.".[70] Moreover, the Court ruled, states had the right to establish qualifications for jurors, which meant that the defendants had been tried by a jury properly selected by those standards.[71]

The issue the Court considered was the newly discovered evidence in the form the affidavit that Victoria Price was a "common prostitute." The court ruled that this evidence could be used to establish only that she had consented. Since not even the defendants contended that she had consented, the evidence was irrelevant and thus properly excluded.

Responding to the dissent of Chief Justice with regard to the shortcomings of the representation at trial of these defendants, the Court stated that their defense had not been pro forma. Attorney Roddy "expressly announced he was there from the beginning at the instance of friends of the accused; but not being paid counsel asked to appear not as paid counsel, but to aid local counsel appointed by the court, and was permitted to so appear." As to attorney Moody, the Court stated "The defendants were represented, as shown by the record and pursuant to appointment by the court by Hon. Milo Moody, an able member of the bar of long and successful experience in the trial of criminal as well as criminal cases." As to the quality of their representation, the Court held, "We do not regard the representation of the accused by counsel as pro forma. A very rigorous and rigid cross-examination was made of the state's witnesses, the alleged victims of the rape especially in the cases first tried. A reading of the records discloses why experienced counsel would not travel over all the same ground in each case. Whether benefit or hurt would have attended an effort to present an argument for accused is purely conjectural.[72][note 6]

Decisions for Weems and Norris

The Court did not revisit the change of venue decision, but simply denied the claimed error with respect to it, citing back to its previous decisions in the Powell and Patterson appeals. The Court summarized the testimony of Victoria Price to the effect that these appellants had thrown the white boys off the "fast moving" train and then raped her with a knife to her throat. The Court then addressed the questions Judge Hawkins had not allowed the defense to ask on cross-examination with regard to Price's prior sexual activity. As to Price those questions were, after first establishing that she was married and not divorced: "Did you leave him (her husband) at Huntsville?" "How long had you known your husband before you married him?" "Were you ever in jail before?" As to the examining physician, Dr. Lynch, the cross-examination questions were: "Both of these girls admitted to you they had had sexual intercourse previous to this, didn't they?" "Both of them told you they had had sexual intercourse, one told you she had been married and the other told you she had been?" "From your examination could you tell whether or not they were subject to intercourse?" "Were they virgins?" "That you find anything in the vagina that indicated to you these girls had had or might have had gonorrhea or syphilis?" And other questions asked of Dr. Lynch "of like import."[31] The Court ruled that these cross examination questions were "immaterial", since they did not go to show that the women had consented.[31] The Court did not address whether this evidence might have shown another way to account for the presence of the semen Dr. Lynch found.