Septimania

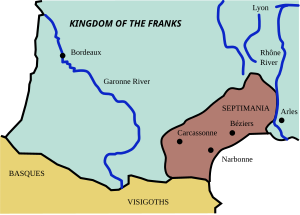

Septimania (French: Septimanie, IPA: [sɛptimani]; Occitan: Septimània, IPA: [septiˈmanjɔ]; Catalan: Septimània, IPA: [səptiˈmaniə]) was the western region of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed under the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septimania was ceded to their king, Theodoric II. Under the Visigoths it was known as simply Gallia or Narbonensis. It corresponded roughly with the modern French region of Languedoc-Roussillon. It passed briefly to the Emirate of Córdoba in the eighth century before its conquest by the Franks, who by the end of the ninth century termed it Gothia or the Gothic March (Marca Gothica).

Septimania was a march of the Carolingian Empire and then West Francia down to the thirteenth century, though it was culturally and politically separate from northern France and the central royal government. The region was under the influence of the people from Toulouse, Provence, and ancient Catalonia. It was part of the cultural and linguistic region named Occitania that was finally brought within the control of the French kings in the early 13th century as a result of the Albigensian Crusade after which it came under French governors. From the end of the thirteenth century it was known as Languedoc and its history is tied up with that of France.

The name "Septimania" may derive from part of the Roman name of the city of Béziers, Colonia Julia Septimanorum Beaterrae, which in turn alludes to the settlement of veterans of the Roman VII Legion in the city. Another possible derivation of the name is in reference to the seven cities (civitates) of the territory: Béziers, Elne, Agde, Narbonne, Lodève, Maguelonne, and Nîmes. Septimania extended to a line halfway between the Mediterranean and the Garonne River in the northwest; in the east the Rhône separated it from Provence; and to the south its boundary was formed by the Pyrenees.

Visigothic Narbonensis

Gothic acquisition of Septimania

Under Theodoric II, the Visigoths settled in Aquitaine as foederati of the Western Roman Empire (450s). Sidonius Apollinaris refers to Septimania as "theirs" during the reign of Avitus (455–456), but Sidonius is probably considering Visigothic settlement of and around Toulouse.[1] The Visigoths were then holding the Toulousain against the legal claims of the Empire, though they had more than once offered to exchange it for the Auvergne.[1]

In 462 the Empire, controlled by Ricimer in the name of Libius Severus, granted the Visigoths the western half of the province of Gallia Narbonensis to settle. The Visigoths occupied Provence (eastern Narbonensis) as well and only in 475 did the Visigothic king, Euric, cede it to the Empire by a treaty whereby the emperor Julius Nepos recognised the Visigoths' full independence.

Kingdom of Narbonne

The Visigoths, perhaps because they were Arians, met with the opposition of the Catholic Franks in Gaul.[2] The Franks allied with the Armorici, whose land was under constant threat from the Goths south of the Loire, and in 507 Clovis I, the Frankish king, invaded the Visigothic kingdom, whose capital lay in Toulouse, with the consent of the leading men of the tribe.[3] Clovis defeated the Goths in the Battle of Vouillé and the child-king Amalaric was carried for safety into Iberia while Gesalec was elected to replace him and rule from Narbonne.

Clovis, his son Theuderic I, and his Burgundian allies proceeded to conquer most of Visigothic Gaul, including the Rouergue (507) and Toulouse (508). The attempt to take Carcassonne, a fortified site guarding the Septimanian coast, was defeated by the Ostrogoths (508) and Septimania thereafter remained in Visigothic hands, though the Burgundians managed to hold Narbonne for a time and drive Gesalec into exile. Border warfare between Gallo-Roman magnates, including bishops, had existed with the Visigoths during the last phase of the Empire and it continued under the Franks.[4]

The Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great reconquered Narbonne from the Burgundians and retained it as the provincial capital. Theudis was appointed regent at Narbonne by Theodoric while Amalaric was still a minor in Iberia. When Theodoric died in 526, Amalaric was elected king in his own right and he immediately made his capital in Narbonne. He ceded Provence, which had at some point passed back into Visigothic control, to the Ostrogothic king Athalaric. The Frankish king of Paris, Childebert I, invaded Septimania in 531 and chased Amalaric to Barcelona in response to pleas from his sister, Chrotilda, that her husband, Amalaric, had been mistreating her. The Franks did not try to hold the province, however. Under Amalaric's successor, however, the centre of gravity of the kingdom crossed the Pyrenees and Theudis made his capital in Barcelona.

Gothic province of Gallia

In the Visigothic kingdom, which became centred on Toledo by the end of the reign of Leovigild, the province of Gallia Narbonensis, usually shortened to just Gallia or Narbonensis and never called Septimania,[1] was both an administrative province of the central royal government and an ecclesiastical province whose metropolitan was the Archbishop of Narbonne. Originally, the Goths may have maintained their hold on the Albigeois, but if so it was conquered by the time of Chilperic I.[5] There is archaeological evidence that some enclaves of Visigothic population remained in Frankish Gaul, near the Septimanian border, after 507.[5]

The province of Gallia held a unique place in the Visigothic kingdom, as it was the only province outside of Iberia, north of the Pyrenees, and bordering a strong foreign nation, in this case the Franks. The kings after Alaric II favoured Narbonne as a capital, but twice (611 and 531) were defeated and forced back to Barcelona by the Franks before Theudis moved the capital there permanently. Under Theodoric Septimania had been safe from Frankish assault, but was raided by Childebert I twice (531 and 541). When Liuva I succeeded the throne in 568, Septimania was a dangerous frontier province and Iberia was wracked by revolts.[6] Liuva granted Iberia to his son Leovigild and took Septimania to himself.[6]

During the revolt of Hermenegild (583–585) against his father Leovigild, Septimania was invaded by Guntram, King of Burgundy, possible in support of Hermenegild's revolt, since the latter was married to his niece Ingundis. The Frankish attack of 585 was repulsed by Hermenegild's brother Reccared, who was ruling Narbonensis as a sub-king. Hermenegild died at Tarragona that year and it is possible that he had escaped confinement in Valencia and was seeking to join up with his Frankish allies.[7] Alternatively, the invasion may have occurred in response to Hermenegild's death.[8] Reccared meanwhile took Beaucaire (Ugernum) on the Rhône near Tarascon and Cabaret (a fort called Ram's Head), both of which lay in Guntram's kingdom.[7][8] Guntram ignored two pleas for a peace in 586 and Reccared undertook the only Visigothic invasion of Francia in response.[8] However, Guntram was not motivated solely by religious alliance with the fellow Catholic Hermenegild, for he invaded Septimania again in 589 and was roundly defeated near Carcassonne by Claudius, Duke of Lusitania.[9] It is clear that the Franks, throughout the sixth century, had coveted Septimania, but were unable to take it and the invasion of 589 was the last attempt.

In the seventh century, Gallia often had its own governors or duces (dukes), who were typically Visigoths. Most public offices were also held by Goths, far out of proportion to their part of the population.[10]

Culture of Gothic Septimania

The native population of Gallia was referred to by Visigothic and Iberian writers as the "Gauls" and there is a well-attested hatred between the Goths and the Gaul which was atypical for the kingdom as a whole.[10] The Gauls commonly insulted the Goths by comparing the strength of their men to that of Gaulish women, though the Spaniards regarded themselves as the defenders and protectors of the Gauls. It is only in the time of Wamba and Julian of Toledo, however, that a large Jewish population becomes evident in Septimania: Julian referred to it as a "brothel of blaspheming Jews."[11]

Thanks to the preserved canons of the Council of Narbonne of 590, a good deal can be known about surviving pagan practices in Visigothic Septimania. The Council may have been responding in part to the orders of the Third Council of Toledo, which found "the sacrilege of idolatry [to be] firmly implanted throughout almost the whole of Iberia and Septimania."[12] The Roman pagan practice of not working Thursdays in honour of Jupiter was still prevalent.[13] The council set down penance to be done for not working on Thursday save for church festivals and commanded the practice of Martin of Braga, rest from rural work on Sundays, to be adopted.[13] Also punished by the council were fortunetellers, who were publicly lashed and sold into slavery.

Different theories exist concerning the nature of the frontier between Septimania and Frankish Gaul. On the one hand, cultural exchange is generally reputed to have been minimal,[14] but the level of trading activity has been disputed. There have been few to no objects of Neustrian, Austrasian, or Burgundian provenance discovered in Septimania.[15] However, a series of sarcophagi of a unique regional style, variously laballed Visigothic, Aquitainian, or south-west Gallic, are prevalent on both sides of the Septimania border.[16] These sarcophagi are made of locally quarried marble from Saint-Béat and are of varied design, but with generally flat relief which distinguishes them from Roman sarcophagi.[16] Their production has been dated to either the 5th, 6th, or 7th century, with the second of these being considered the most likely today.[17] However, if they were made in the 5th century, while both Aquitaine and Septimani were in Visigothic hands, their existence provides no evidence for a cultural osmosis across the Gothic-Frankish frontier. A unique style of orange pottery was common in the 4th and 5th centuries in southern Gaul, but the later (6th century) examples culled from Septimania are more orange than their cousins from Aquitaine and Provence and are not found commonly outside of Septimania, a strong indicator that there was little commerce over the frontier or at its ports.[18] In fact, Septimania helped to isolate both Aquitaine and Iberia from the rest of the Mediterranean world.[19]

Coinage of the Visigothic kingdom of Hispania did not circulate in Gaul outside of Septimania and Frankish coinage did not circulate in the Visigothic kingdom, including Septimania. If there had been a significant amount of commerce over the frontier, the monies paid had to have been melted down immediately and re-minted as foreign coins have not been preserved across the frontier.[20]

Muslim Septimania

The Arabs, under Al-Samh ibn Malik, the governor-general of al-Andalus, sweeping up the Iberian peninsula, by 719 overran Septimania; al-Samh set up his capital from 720 at Narbonne, which the Moors called "Arbuna", offering the still largely Arianist Christian inhabitants generous terms and quickly pacifying the other cities. Following the conquest, al-Andalus was divided into five administrative areas, roughly corresponding to present Andalusia, Galicia and Lusitania, Castile and Léon, Aragon and Catalonia, and the ancient province of Septimania.[21] With Narbonne secure, and equally important, its port, for the Arab mariners were masters now of the Western Mediterranean, al-Samh swiftly subdued the largely unresisting cities, still controlled by their Visigoth counts: taking Alet and Béziers, Agde, Lodève, Maguelonne and Nîmes.

By 721 he was reinforced and ready to lay siege to Toulouse, a possession that would open up bordering Aquitaine to him on the same terms as Septimania. But his plans were thwarted in the disastrous Battle of Toulouse (721), with immense losses, in which al-Samh was so seriously wounded that he soon died at Narbonne. Arab forces, soundly based in Narbonne and easily resupplied by sea, struck in the 720s, conquering Carcassonne on the north-western fringes of Septimania (725) and penetrating eastwards as far as Autun (725).

In 731, the Berber lord of the region of Cerdagne Uthman ibn Naissa, called "Munuza" by the Franks, was an ally of the Duke of Aquitaine Odo the Great after he revolted against Cordova, but the rebel lord was defeated and killed by Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, so opening Aquitaine to the Umayyads.

After capturing Bordeaux on the wake of duke Hunald's detachment attempt, Charles Martel directed his attention to Septimania and Provence. While his reasons for leading a military expedition south remain unclear, it seems that he wanted to seal his newly secured grip on Burgundy, now threatened by Umayyad occupation of several cities lying in the lower Rhone, or maybe it provided the excuse he needed to intervene in this territory ruled by Gothic and Roman law, far off from the Frankish centre in the north of Gaul. In 737 the Frankish leader went on to attack Narbonne, but the city held firm, defended by its Goths and Jews under the command of its governor Yusuf, 'Abd er-Rahman's heir. Charles had to go back north without subduing Narbonne, leaving behind a trail of destroyed cities, i.e. Avignon, Nîmes and other Septimanian fortresses.

Around 747 the government of the Septimania region (and the Upper Mark, from Pyrénées to Ebro River) was given to Aumar ben Aumar. In 752 Pippin headed south to Septimania. Gothic counts of Nîmes, Melguelh, Agde and Béziers refused allegiance to the emir at Cordova and declared their loyalty to the Frankish king—the count of Nîmes, Ansemund, having some authority over the remaining counts. The Gothic counts and the Franks then began to besiege Narbonne, where Miló was probably the count (as successor of the count Gilbert). However, the strongly Gothic Narbonne under Muslim rule resisted to the Carolingian thrust. Moreover, attacks on the rearguard by a Basque army under the Aquitanian duke Waifer didn't make things easy to Pippin.

In 754 an anti-Frank reaction, led by Ermeniard, killed Ansemund, but the uprising was without success and Radulf was designated new count by the Frankish court. About 755 Abd al-Rahman ben Uqba replaced Aumar ben Aumar. Narbonne capitulated in 759 only after Pippin promised the defenders of the city to uphold the Gothic law, and the county was granted to Miló, the Gothic count in Muslim times, thus earning the loyalty of Septimania's Goths against Waifer.

Islamic burials have been found in Nîmes[22][23][24][25]

Gothia in Carolingian times

The region of Roussillon was taken by the Franks in 760. Pepin then diverted northwest to Aquitaine, so triggering the war against Waifer of Aquitaine. Albi, Rouergue, Gévaudan and the city of Toulouse were conquered. In 777 the wali of Barcelona, Sulayman al-Arabi, and the wali of Huesca Abu Taur, offered their submission to Charlemagne and also the submission of Husayn, wali of Zaragoza. When Charlemagne invaded the Upper Mark in 778, Husayn refused allegiance and he had to retire. In the Pyrenees, the Basques defeated his forces in Roncesvalles (August 15, 778).

The Frankish king found Septimania and the borderlands so devastated and depopulated by warfare, with the inhabitants hiding among the mountains, that he made grants of land that were some of the earliest identifiable fiefs to Visigothic and other refugees. Charlemagne also founded several monasteries in Septimania, around which the people gathered for protection. Beyond Septimania to the south Charlemagne established the Spanish Marches in the borderlands of his empire.

The territory passed to Louis, king in Aquitaine, but it was governed by Frankish margraves and then dukes (from 817) of Septimania.

The Frankish noble Bernat of Septimania was the ruler of these lands from 826 to 832. His career (he was beheaded in 844) characterized the turbulent 9th century in Septimania. His appointment as Count of Barcelona in 826 occasioned a general uprising of the Catalan lords (Bellonids) at this intrusion of Frankish power over the lands of Gothia. For suppressing Berenguer of Toulouse and the Catalans, Louis the Pious rewarded Bernat with a series of counties, which roughly delimit 9th century Septimania: Narbonne, Béziers, Agde, Magalona, Nîmes and Uzés. Rising against Charles the Bald in 843, Bernat was apprehended at Toulouse and beheaded. Bernat's son, known as Bernat of Gothia, also served as Count of Barcelona and Girona, and as Margrave of Gothia and Septimania from 865 to 878.

Septimania became known as Gothia after the reign of Charlemagne. It retained these two names while it was ruled by the counts of Toulouse during early part of the Middle Ages, but other names became regionally more prominent such as, Roussillon, Conflent, Razès or Foix, and the name Gothia (along with the older name Septimania) faded away during the 10th century, as the region fractured into smaller feudal entities, which sometimes retained Carolingian titles, but lost their Carolingian character, as the culture of Septimania evolved into the culture of Languedoc. This fragmentation in small feudal entities and the resulting fading and the gradual shifting of the name Gothia are the most probable origins of the ancient geographical area known as Gathalania or Cathalania which has reached our days as the present region of Catalonia.

The name was used because the area was populated by a higher concentration of Goths than in surrounding regions. The rulers of this area, when joined with several counties, were titled the Marquesses of Gothia (and, also, the Dukes of Septimania).

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c James (1980), p. 223

- ^ Bachrach (1971), p. 7

- ^ Bachrach (1971), pp. 10–11

- ^ Bachrach (1971), p. 16

- ^ a b James (1980), p. 236

- ^ a b Thompson (1969), p. 19

- ^ a b Collins (2004), p. 60

- ^ a b c Thompson (1969), p. 75

- ^ Thompson (1969), p. 95

- ^ a b Thompson (1969), p. 227

- ^ Thompson (1969), p. 228

- ^ Thompson (1969), p. 54

- ^ a b McKenna (1938), pp. 117–118

- ^ Thompson (1969), p. 23

- ^ James (1980), pp. 228–229

- ^ a b James (1980), p. 229

- ^ James (1980), p. 230

- ^ James (1980), p. 238

- ^ James (1980), pp. 240–241

- ^ James (1980), p. 239

- ^ O'Callaghan (1983), p. 142

- ^ Netburn, Deborah (24 February 2016). "Earliest Known Medieval Muslim Graves are Discovered in France". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (24 February 2016). "Medieval Muslim Graves in France Reveal a Previously Unseen History". Ars Technica.

- ^ "France's Earliest 'Muslim Burials' Found". BBC News. 25 February 2016.

- ^ Gleize, Yves; Mendisco, Fanny; Pemonge, Marie-Hélène; Hubert, Christophe; Groppi, Alexis; Houix, Bertrand; Deguilloux, Marie-France; Breuil, Jean-Yves (24 February 2016). "Early Medieval Muslim Graves in France: First Archaeological, Anthropological and Palaeogenomic Evidence". PLOS ONE.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Sources

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1971). Merovingian Military Organization, 481–751. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain, 710–97. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Collins, Roger (2004). Visigothic Spain, 409–711. Blackwell Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - James, Edward (1980). "Septimania and its frontier: an archaeological approach". In Edward James (ed.). Visigothic Spain: New Approaches. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewis, Archibald Ross (1965). The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McKenna, Stephen (1938). Paganism and Pagan Survivals in Spain up to the Fall of the Visigothic Kingdom. Catholic University of America Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (1983). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, E. A. (1969). The Goths in Spain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zuckerman, Arthur J. (1972) [1965]. A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France 768–900. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03298-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)