Palaeoloxodon falconeri

| Palaeoloxodon falconeri Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton, Nebraska State Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | †Palaeoloxodon |

| Species: | †P. falconeri

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Palaeoloxodon falconeri (Busk, 1867)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Palaeoloxodon falconeri is an extinct species of dwarf elephant from the Middle Pleistocene (around 500–200,000 years ago) of Sicily and Malta. It is amongst the smallest of all dwarf elephants, under 1 metre (3.3 ft) in height as fully grown adults. A member of the genus Palaeoloxodon, it derived from a population of the mainland European straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus).

Chronology

[edit]Palaeoloxodon falconeri derives from the 4 metre tall straight-tusked elephant (P. antiquus), which arrived in Europe approximately 800,000 years ago. The oldest radiometrically dated fossils of Palaeoloxodon on Sicily date to around 500,000 years ago, with the colonisation possibly occurring as early as 690,000 years ago or earlier. P. falconeri's ancestors most likely reached Sicily from the Italian mainland, likely via a series of islands that now form part of the southern Calabrian peninsula.[1] The chronology of the species compared to that of the larger endemic species of Palaeoloxodon on Malta and Sicily, the 2 m (6.6 ft) tall Palaeoloxodon mnaidriensis, is somewhat uncertain. It is generally thought that P. falconeri is the earlier species dating to the Middle Pleistocene, and that P. mnaidriensis descends from a subsequent separate late Middle Pleistocene colonisation of the island by P. antiquus,[2][1] suggested to date to approximately 200,000 years ago.[3] P. falconeri also occurs on Malta, but is generally shorter making it a possible subspecies. It likely dispersed to Malta from Sicily during episodes of low sea level. The chronology of Maltese localities is poorly constrained.[1] The important locality of Spinagallo Cave in southeast Sicily where a large sample of P. falconeri individuals have been found is suggested to date to around 366-233,000 years ago based on optically stimulated luminescence dating and uranium–thorium dating.[1]

Taxonomy

[edit]In 1867, George Busk had proposed the species Elephas falconeri for many of the smallest molars selected from the material originally ascribed by Hugh Falconer (for whom the species is named) to Palaeoloxodon melitensis for the Maltese dwarf elephant, a possible subspecies of P. falconeri.[4][5] The species Elephas/Palaeoloxodon melitensis, formerly considered a distinct species, is now considered a synonym of P. falconeri.[6]

Description

[edit]

Palaeoloxodon falconeri is considered to be a textbook example of insular dwarfism, with adult individuals around the size of modern elephant calves, drastically smaller than their mainland ancestors. In a 2015 study of specimens from Spinagallo Cave, a composite adult male specimen MPUR/V n1 was estimated to measure 96.5 cm (3 ft 2.0 in) in shoulder height about 305 kg (672 lb) in weight, a composite adult female specimen MPUR/V n2 80 cm (2 ft 7.5 in) in shoulder height and about 168 kg (370 lb) in weight, and a composite newborn male specimen MPUR/V n3 33 cm (1 ft 1.0 in) in shoulder height and about 6.7 kg (15 lb) in weight.[7] A later 2019 volumetric study revised the weight estimates for the adult male and adult female to about 250 kg (551 lb) and 150.5 kg (332 lb) respectively. The newborn male of the species was estimated in the same study to weigh 7.8 kg (17 lb).[6] This makes P. falconeri the smallest known elephant species, along with the roughly equivalently sized but much more poorly known Palaeoloxodon cypriotes of Cyprus.[8]

The morphology of the skull demonstrates neotenic traits similar to those present in juvenile elephants, including the loss of the fronto-parietal crest present in other Palaeoloxodon species. The brain was around the size of a human's, and proportionally much larger relative to skull and body size than P. antiquus. In comparison to adult P. antiquus individuals, the neck was elongated, the torso was proportionally wider and longer, and the forelimbs were shorter while the hindlimbs were longer, resulting in a concave back. The limbs were proportionally more slender than P. antiquus, presumably because they needed to bear less weight.[7] The feet were more digitigrade than modern elephants due to being proportionally narrower and higher.[6] The morphology of the limbs and feet suggest that P. falconeri may have been more nimble than living elephants, and better able to move on steep and uneven terrain. Female members of the species were tuskless. Due to the much smaller body size resulting in increased heat loss, it is possible that the species was covered by a more dense coat of hair than present in living elephants in order to maintain a stable body temperature, though if it was present it was still likely sparse, due to elephants lacking sweat glands. The ears were also likely proportionally much smaller than living elephants for similar thermodynamic reasons.[7] Histology analysis of their bones, teeth and tusks demonstrates that despite their small size, individuals of P. falconeri grew very slowly, reaching sexual maturity at around 15 years of age (older than living elephants), with some individuals aged around 22 still having unfused limb bone epiphyses, indicating that they were still growing. The growth rate was only slightly lower post-sexual maturity, which constrasts with African bush elephants, whose growth slows considerably after sexual maturity. At least one individual reached a lifespan of at minimum 68 years, comparable to full-sized elephants.[9] Dental microwear suggests that P. falconeri was a mixed feeder (both browsing and grazing).[10]

Ecology

[edit]Sicily and Malta during the time of P. falconeri exhibited a depauperate fauna, with the only other terrestrial mammal species on the islands being the cat-sized giant dormouse Leithia (the largest dormouse ever) as well as the giant dormouse Maltamys, the otter Nesolutra, and the shrew Crocidura esuae which is possibly the ancestor of the living Sicilian shrew, C. sicula[11] though this is disputed[12] (the presence of a fox of the genus Vulpes has been suggested but is unconfirmed).[2][13] Sicily was also inhabited by a variety of bird species,[14] as well as frogs (Discoglossus, Bufotes, Hyla), lizards (Lacerta), snakes (Hierophis, Natrix), pond turtles, tortoises (including the large Solitudo[15] and smaller Hermann's tortoise), and bats.[2]

Extinction

[edit]Palaeoloxodon falconeri became extinct on Sicily around 200,000 years ago,[3] due to the tectonic uplift of northeast Sicily and Calabria resulting in a narrowing of the distance between the island and the Italian mainland, similar to the geography in the region today, allowing a number of large mammal species from mainland Italy to colonise the island, including carnivores like cave hyenas, cave lions, grey wolves, brown bears, and red foxes, and herbivores like wild boar, red deer, fallow deer, aurochs, steppe bison and the hippo Hippopotamus pentlandi.[2] The straight-tusked elephant again recolonised the island during this episode, giving rise to Palaeoloxodon mnaidriensis, which though strongly dwarfed, was considerably larger than P. falconeri, with its larger body size likely a reaction to these large predators and competitors.[16]

Gallery

[edit]-

Reconstruction

-

Skeletons in Milan Natural History Museum

-

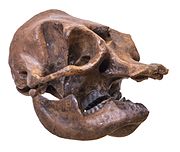

Skull at MUSE - Science Museum in Trento

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Scarborough, Matthew Edward (March 2022). "Extreme Body Size Variation in Pleistocene Dwarf Elephants from the Siculo-Maltese Palaeoarchipelago: Disentangling the Causes in Time and Space". Quaternary. 5 (1): 17. doi:10.3390/quat5010017. hdl:11427/36354. ISSN 2571-550X.

- ^ a b c d Bonfiglio, L., Marra, A. C., Masini, F., Pavia, M., & Petruso, D. (2002). Pleistocene faunas of Sicily: a review. In W. H. Waldren, & J. A. Ensenyat (Eds.), World islands in prehistory: international insular investigations. British Archaeological Reports, International Series, 1095, 428–436.

- ^ a b Baleka, Sina; Herridge, Victoria L.; Catalano, Giulio; Lister, Adrian M.; Dickinson, Marc R.; Di Patti, Carolina; Barlow, Axel; Penkman, Kirsty E.H.; Hofreiter, Michael; Paijmans, Johanna L.A. (August 2021). "Estimating the dwarfing rate of an extinct Sicilian elephant". Current Biology. 31 (16): 3606–3612.e7. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E3606B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.037. PMID 34146486. S2CID 235477150.

- ^ Busk, G. (1867). Description of the remains of three extinct species of elephant, collected by Capt. Spratt, C.B.R.N., in the ossiferous cavern of Zebbug, in the island of Malta. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 6: 227–306.

- ^ Palombo, M.R. (2001). Endemic elephants of the Mediterranean Islands: knowledge, problems and perspectives. The World of Elephants, Proceedings of the 1st International Congress (October 16–20, 2001, Rome): 486–491.

- ^ a b c Romano, Marco; Manucci, Fabio; Palombo, Maria Rita (2021-03-04). "The smallest of the largest: new volumetric body mass estimate and in-vivo restoration of the dwarf elephant Palaeoloxodon ex gr. P. falconeri from Spinagallo Cave (Sicily)". Historical Biology. 33 (3): 340–353. Bibcode:2021HBio...33..340R. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1617289. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 181855906.

- ^ a b c Larramendi, A.; Palombo, M. R. (2015). "Body Size, Biology and Encephalization Quotient of Palaeoloxodon ex gr. P. falconeri from Spinagallo Cave (Hyblean plateau, Sicily)". Hystrix: The Italian Journal of Mammalogy. 26 (2): 102–109. doi:10.4404/hystrix-26.2-11478.

- ^ Athanassiou, Athanassios; Herridge, Victoria; Reese, David S.; Iliopoulos, George; Roussiakis, Socrates; Mitsopoulou, Vassiliki; Tsiolakis, Efthymios; Theodorou, George (August 2015). "Cranial evidence for the presence of a second endemic elephant species on Cyprus". Quaternary International. 379: 47–57. Bibcode:2015QuInt.379...47A. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.05.065.

- ^ Köhler, Meike; Herridge, Victoria; Nacarino-Meneses, Carmen; Fortuny, Josep; Moncunill-Solé, Blanca; Rosso, Antonietta; Sanfilippo, Rossana; Palombo, Maria Rita; Moyà-Solà, Salvador (2021-11-24). "Palaeohistology reveals a slow pace of life for the dwarfed Sicilian elephant". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 22862. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1122862K. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-02192-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8613187. PMID 34819557.

- ^ Palombo, Maria R. (December 2009). "Body size structure of Pleistocene mammalian communities: what support is there for the "island rule"?". Integrative Zoology. 4 (4): 341–356. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2009.00175.x. PMID 21392307. S2CID 31931880.

- ^ Guglielmo, Marilisa; Marra, Antonella, Cinzia (2011). "Le due Sicilie del Pleistocene Medio: osservazioni paleobiogeografiche" [The two Sicilies of the Middle Pleistocene: paleobiogeographic observations]. Biogeographia – the Journal of Integrative Biogeography (in Italian). 30. doi:10.21426/B630110597. ISSN 1594-7629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ MANUEL LÓPEZ-GARCÍA, JUAN; BLAIN, HUGUES-ALEXANDRE; PAGANO, ENRICO; OLLÉ, ANDREU; MARIA VERGÈS, JOSEP; FORGIA, VINCENZA (2013-07-31). "The Small Mammals (Insectivores, Bats and Rodents) from the Holocene Archaeological Site of Vallone Inferno (Scillato, Lower Imera Valley, Northwestern Sicily)". Rivista italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 119: 2. doi:10.13130/2039-4942/6037.

- ^ Palombo, Maria Rita (July 2007). "How can endemic proboscideans help us understand the "island rule"? A case study of Mediterranean islands". Quaternary International. 169–170: 105–124. Bibcode:2007QuInt.169..105P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2006.11.002.

- ^ Pavia, Marco; Insacco, Gianni (2013). "The fossil bird associations from the early Middle Pleistocene of the Ragusa province (SE Sicily, Italy)" (PDF). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana (3). doi:10.4435/BSPI.2013.14 (inactive 2024-11-20). ISSN 0375-7633. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-16.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Valenti, Pietro; Vlachos, Evangelos; Kehlmaier, Christian; Fritz, Uwe; Georgalis, Georgios L; Luján, Àngel Hernández; Miccichè, Roberto; Sineo, Luca; Delfino, Massimo (2022-11-28). "The last of the large-sized tortoises of the Mediterranean islands". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 196 (4): 1704–1717. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac044. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ van der Geer, Alexandra A. E.; van den Bergh, Gerrit D.; Lyras, George A.; Prasetyo, Unggul W.; Due, Rokus Awe; Setiyabudi, Erick; Drinia, Hara (August 2016). "The effect of area and isolation on insular dwarf proboscideans". Journal of Biogeography. 43 (8): 1656–1666. Bibcode:2016JBiog..43.1656V. doi:10.1111/jbi.12743. ISSN 0305-0270.