Spatial network

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

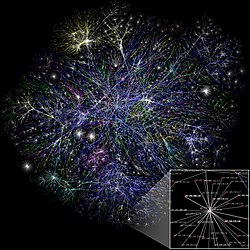

A spatial network (sometimes also geometric graph) is a graph in which the vertices or edges are spatial elements associated with geometric objects, i.e., the nodes are located in a space equipped with a certain metric.[1][2] The simplest mathematical realization of spatial network is a lattice or a random geometric graph, where nodes are distributed uniformly at random over a two-dimensional plane; a pair of nodes are connected if the Euclidean distance is smaller than a given neighborhood radius. Transportation and mobility networks, Internet, mobile phone networks, power grids, social and contact networks and biological neural networks are all examples where the underlying space is relevant and where the graph's topology alone does not contain all the information. Characterizing and understanding the structure, resilience and the evolution of spatial networks is crucial for many different fields ranging from urbanism to epidemiology.

Examples

An urban spatial network can be constructed by abstracting intersections as nodes and streets as links, which is referred to as a transportation network. Beijing traffic was studied as a dynamic network and its percolation properties have been found useful to identify systematic bottlenecks.[3]

One might think of the 'space map' as being the negative image of the standard map, with the open space cut out of the background buildings or walls.[4]

Characterizing spatial networks

The following aspects are some of the characteristics to examine a spatial network:[1]

- Planar networks

In many applications, such as railways, roads, and other transportation networks, the network is assumed to be planar. Planar networks build up an important group out of the spatial networks, but not all spatial networks are planar. Indeed, the airline passenger networks is a non-planar example: Many large airports in the world are connected through direct flights.

- The way it is embedded in space

There are examples of networks, which seem to be not "directly" embedded in space. Social networks for instance connect individuals through friendship relations. But in this case, space intervenes in the fact that the connection probability between two individuals usually decreases with the distance between them.

- Voronoi tessellation

A spatial network can be represented by a Voronoi diagram, which is a way of dividing space into a number of regions. The dual graph for a Voronoi diagram corresponds to the Delaunay triangulation for the same set of points. Voronoi tessellations are interesting for spatial networks in the sense that they provide a natural representation model to which one can compare a real world network.

- Mixing space and topology

Examining the topology of the nodes and edges itself is another way to characterize networks. The distribution of degree of the nodes is often considered, regarding the structure of edges it is useful to find the Minimum spanning tree, or the generalization, the Steiner tree and the relative neighborhood graph.

Lattice networks

Lattice networks (see Fig. 1) are useful models for spatial embedded networks. Many physical phenomenas have been studied on these structures. Examples include Ising model for spontaneous magnetization,[5] diffusion phenomena modeled as random walks[6] and percolation.[7] Recently to model the resilience of interdependent infrastructures which are spatially embedded a model of interdependent lattice networks was introduced (see Fig. 2) and analyzed[8] .[9] A spatial multiplex model was introduced by Danziger et al[10] and was analyzed further by Vaknin et al.[11] For the model see Fig. 3. It was shown that localized attacks on these two last models (shown in Figs. 2 and 3) above a critical radius will lead to cascading failures and system collapse. [12] Percolation in a single 2d layer structure (like Fig. 3) of links having characteristic length have been found to have a very rich behavior.[13] In particular, the behavior up to linear scales of is like in high dimensional systems (mean field) at the critical percolation threshold. Above the system behaves like a regular 2d system.

Spatial modular networks

Many real-world infrastructure networks are spatially embedded and their links have characteristics length such as pipelines, power lines or ground transportation lines are not homogeneous, like in Fig. 3, but rather heterogeneous. For example, density of links within cities are significantly higher than between cities. Gross et al.[14] developed and studied a similar realistic heterogeneous spatial modular model using percolation theory in order to better understand the effect of heterogeneity on such networks. The model assumes that inside a city there are many lines connecting different locations, while long lines between the cities are sparse and usually directly connecting only a few nearest neighbors cities in a two dimensional plane, see Fig. 4. It is found that this heterogeneous model experiences two distinct percolation transitions, one when the cities disconnect from each other and the second when each city breaks apart. This is in contrast to the homogeneous model, Fig. 3 where a single transition is found.

Probability and spatial networks

In the "real" world many aspects of networks are not deterministic - randomness plays an important role. For example, new links, representing friendships, in social networks are in a certain manner random. Modelling spatial networks in respect of stochastic operations is consequent. In many cases the spatial Poisson process is used to approximate data sets of processes on spatial networks. Other stochastic aspects of interest are:

- The Poisson line process

- Stochastic geometry: the Erdős–Rényi graph

- Percolation theory

Approach from the theory of space syntax

Another definition of spatial network derives from the theory of space syntax. It can be notoriously difficult to decide what a spatial element should be in complex spaces involving large open areas or many interconnected paths. The originators of space syntax, Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson use axial lines and convex spaces as the spatial elements. Loosely, an axial line is the 'longest line of sight and access' through open space, and a convex space the 'maximal convex polygon' that can be drawn in open space. Each of these elements is defined by the geometry of the local boundary in different regions of the space map. Decomposition of a space map into a complete set of intersecting axial lines or overlapping convex spaces produces the axial map or overlapping convex map respectively. Algorithmic definitions of these maps exist, and this allows the mapping from an arbitrary shaped space map to a network amenable to graph mathematics to be carried out in a relatively well defined manner. Axial maps are used to analyse urban networks, where the system generally comprises linear segments, whereas convex maps are more often used to analyse building plans where space patterns are often more convexly articulated, however both convex and axial maps may be used in either situation.

Currently, there is a move within the space syntax community to integrate better with geographic information systems (GIS), and much of the software they produce interlinks with commercially available GIS systems.

History

While networks and graphs were already for a long time the subject of many studies in mathematics, physics, mathematical sociology, computer science, spatial networks have been also studied intensively during the 1970s in quantitative geography. Objects of studies in geography are inter alia locations, activities and flows of individuals, but also networks evolving in time and space.[15] Most of the important problems such as the location of nodes of a network, the evolution of transportation networks and their interaction with population and activity density are addressed in these earlier studies. On the other side, many important points still remain unclear, partly because at that time datasets of large networks and larger computer capabilities were lacking. Recently, spatial networks have been the subject of studies in Statistics, to connect probabilities and stochastic processes with networks in the real world.[16]

See also

- Hyperbolic geometric graph

- Spatial network analysis software

- Cascading failure

- Complex network

- Planar graphs

- Percolation theory

- Modularity (networks)

- Random graphs

- Topological graph theory

- Small-world network

- Chemical graph

- Interdependent networks

References

- ^ a b Barthelemy, M. (2011). "Spatial Networks". Physics Reports. 499 (1–3): 1–101. arXiv:1010.0302. Bibcode:2011PhR...499....1B. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2010.11.002. S2CID 4627021.

- ^ M. Barthelemy, "Morphogenesis of Spatial Networks", Springer (2018).

- ^ Li, D.; Fu, B.; Wang, Y.; Lu, G.; Berezin, Y.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. (2015). "Percolation transition in dynamical traffic network with evolving critical bottlenecks". PNAS. 112 (3): 669–672. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112..669L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419185112. PMC 4311803. PMID 25552558.

- ^ Hillier B, Hanson J, 1984, The social logic of space (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK).

- ^ McCoy, Barry M.; Wu, Tai Tsun (1968). "Theory of a Two-Dimensional Ising Model with Random Impurities. I. Thermodynamics". Physical Review. 176 (2): 631–643. Bibcode:1968PhRv..176..631M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.176.631. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Masoliver, Jaume; Montero, Miquel; Weiss, George H. (2003). "Continuous-time random-walk model for financial distributions". Physical Review E. 67 (2): 021112. arXiv:cond-mat/0210513. Bibcode:2003PhRvE..67b1112M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.67.021112. ISSN 1063-651X. PMID 12636658. S2CID 2966272.

- ^ Bunde, Armin; Havlin, Shlomo (1996). Bunde, Armin; Havlin, Shlomo (eds.). Fractals and Disordered Systems. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-84868-1. ISBN 978-3-642-84870-4.

- ^ Li, Wei; Bashan, Amir; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Stanley, H. Eugene; Havlin, Shlomo (2012). "Cascading Failures in Interdependent Lattice Networks: The Critical Role of the Length of Dependency Links". Physical Review Letters. 108 (22): 228702. arXiv:1206.0224. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108v8702L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.228702. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 23003664. S2CID 5233674.

- ^ Bashan, Amir; Berezin, Yehiel; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Havlin, Shlomo (2013). "The extreme vulnerability of interdependent spatially embedded networks". Nature Physics. 9 (10): 667–672. arXiv:1206.2062. Bibcode:2013NatPh...9..667B. doi:10.1038/nphys2727. ISSN 1745-2473. S2CID 12331944.

- ^ Danziger, Michael M.; Shekhtman, Louis M.; Berezin, Yehiel; Havlin, Shlomo (2016). "The effect of spatiality on multiplex networks". EPL. 115 (3): 36002. arXiv:1505.01688. Bibcode:2016EL....11536002D. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/115/36002. ISSN 0295-5075.

- ^ Vaknin, Dana; Danziger, Michael M; Havlin, Shlomo (2017). "Spreading of localized attacks in spatial multiplex networks". New Journal of Physics. 19 (7): 073037. arXiv:1704.00267. Bibcode:2017NJPh...19g3037V. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/aa7b09. ISSN 1367-2630. S2CID 9121930.

- ^ Localized attacks on spatially embedded networks with dependencies Y. Berezin, A. Bashan, M.M. Danziger, D. Li, S. Havlin Scientific Reports 5, 8934 (2015)

- ^ "Critical stretching of mean-field regimes in spatial networks". Phys. Rev. Lett. 123 (8): 088301. 2019. arXiv:1704.00268. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.088301. PMC 7219511. PMID 31491213.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Bnaya Gross, Dana Vaknin, Sergey Buldyrev, Shlomo Havlin (2020). "Two transitions in spatial modular networks". New Journal of Physics. 22 (5): 053002. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/ab8263.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ P. Haggett and R.J. Chorley. Network analysis in geog- raphy. Edward Arnold, London, 1969.

- ^ "Spatial Networks".

- Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Chepoi, Victor (2008). "Metric graph theory and geometry: a survey" (PDF). Contemp. Math. Contemporary Mathematics. 453: 49–86. doi:10.1090/conm/453/08795. ISBN 9780821842393. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-25.

- Pach, János; et al. (2004). Towards a Theory of Geometric Graphs. Contemporary Mathematics, no. 342, American Mathematical Society.

- Pisanski, Tomaž; Randić, Milan (2000). "Bridges between geometry and graph theory". In Gorini, C. A. (ed.). Geometry at Work: Papers in Applied Geometry. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America. pp. 174–194. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.