TMS9900

| Designer | Texas Instruments |

|---|---|

| Bits | 16-bit |

| Introduced | 1976 |

| Design | CISC |

| Endianness | Big |

| Registers | |

| PC, WP, ST | |

| General-purpose | 2 internally located in processor (WP, ST) 16 × 16-bit workspace located in external RAM |

The TMS9900 was one of the first commercially available single-chip 16-bit microprocessors.[a] Introduced in June 1976, it implemented Texas Instruments's TI-990 minicomputer architecture in a single-chip format, and was initially used for low-end models of that lineup.

Its 64-pin DIP format made it more expensive to implement in smaller machines than the more common 40-pin format, and it saw relatively few design wins outside TI's own use. Among those uses was their TI-99/4 and TI-99/4A home computers, which ultimately sold about 2.8 million units.

Microcomputer-on-chip implementations of variations of the 9900 in 40-pin packages included the TMS9940, TMS9980/81, and TMS9995.

The SBP9900 was a ruggedized version.[1]

The last generation was the 99000 series, created to be the CPU of the 990/10A in 1981. The TMS99105 and 110 were sold as catalog parts. [2]

By the mid-1980s, the microcomputer field was moving to 16-bit systems such as the Intel 8086 and newer 16/32-bit designs such as the Motorola 68000. With no obvious future for the chip, TI's Semiconductor division turned its attention to special-purpose 32-bit processors: the Texas Instruments TMS320, introduced in 1983, and the Texas Instruments TMS340 graphics processor.

The 9900 architecture lived on into the 1990s as the Communications Processor in TI's TMS380 chipset for Token Ring networking (later Ethernet).[3]

History

[edit]

The TMS9900 was designed as a single-chip version of the TI 990 minicomputer series, much like the Intersil 6100 was a single chip PDP-8 (12 bits), and the Fairchild 9440 and Data General mN601 were both one-chip versions of Data General's Nova. Unlike multi-chip 16-bit microprocessors such as the National Semiconductor IMP-16 or DEC LSI-11, some of which predated the TMS9900, the 9900 was a single-chip, self-contained 16-bit microprocessor.

The minicomputer roots of the TMS9900 give rise to a number of architectural features that are not commonly found on designs that started from a blank sheet. Notable among these was the TMS9900's use of processor registers that are mapped into main memory.[4] This allows for fast context switching, which can be accomplished by changing a single register, the Workspace Pointer, to point to the first entry in a list of register values. More traditional designs would require the entire set of internal registers to be stored out to memory or the stack.

The downside to this approach is that accessing these registers is much slower. In a minicomputer implementation with fast memory, the effect is relatively small and the upside in a real-time or multi-tasking environment is significant as context switches are common. In other roles, like single-user microcomputers, this tradeoff may not be worthwhile. The 40-pin implementations of the 9900 included 128 or 256 bytes of fast onboard RAM for registers.

TI used the same architecture across different divisions for corporate synergy: "one company, one computer architecture". In the late 1970s Walden C. Rhines gave a presentation of the TMS99110, then code-named "Alpha",[5] to an IBM group developing a personal computer. "We wouldn't know until 1981 just what we had lost" because IBM chose the Intel 8088 for the IBM PC, he recalled. One factor was the lack of a roadmap for accessing more than 64KB of logical memory. The 9900 family could expand its address space to 16 MiB only by page-mapping; the 9900 could address 256K through segments.

After dropping out of the personal computer market after products such as TI-99/4A, the company microprocessor division eventually switched focus to the TMS320 special-purpose processor series.[6]

Architecture

[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The TMS9900 has three internal 16-bit registers — the Program counter (PC), the Status register (ST), and the Workspace Pointer register (WP).[7] The WP points to a base address in external RAM where 16 general purpose user registers (each 16 bits wide) reside to serve the processor. This architecture allows for quick context switching; e.g. when a subroutine is entered, only the single workspace register needs to be changed instead of requiring registers to be saved individually. As with the Motorola 68000, bits are numbered with the MSB (most significant bit) being bit 0.

Addresses refer to bytes with big endian ordering convention. The TMS9900 is a classic 16-bit machine with an address space of 216 bytes (65,536 bytes or 32,768 words).

There is no dedicated stack pointer register. Instead, branch instructions exist that save the program counter to a register (BL — Branch and Link), or change the register context (BLWP — Branch and Link Workspace Pointer, or XOP). The 16 hardware and 16 software interrupt vectors each consist of a pair of PC and WP values, so the register context switch is automatically performed by an interrupt as well. Stacks can be implemented atop either of these mechanisms.[8]

Instruction set and addressing

[edit]The TMS9900 has 69 instructions which are either one, two, or three words long and are always word-aligned in memory. The instruction set is fairly orthogonal, meaning that, with few exceptions, instructions can use all methods of accessing operands (addressing modes).

Addressing modes include Immediate (operand in instruction), Direct or "Symbolic" (operand address in instruction), Register (operand in workspace register), Register Indirect (operand address in workspace register) with or without auto-increment, Indexed (operand address in instruction indexed with workspace register content), and Program Counter Relative.

The most important dual-operand instructions (add, subtract, compare, move etc.) have 2-bit addressing mode and 4-bit register selector fields for both source and destination operands. In the opcode, "Symbolic" mode is represented as Indexed mode with the register field set to 0, therefore workspace register 0 (WR0) cannot be used in Indexed mode. In less-frequently-used dual-operand instructions such as XOR, the destination operand must be a workspace register (or workspace register pair in the case of multiply and divide instructions).

Flow control is facilitated through a group of one unconditional and 12 conditional jump instructions. Jump targets are relative to the PC with an offset of -128 to +127 word addresses.

For subroutine calls, the Branch and Load Workspace Pointer (BLWP) instruction loads new WP and PC values, then saves the values of WP, PC, and ST to (new) registers 13, 14, and 15 respectively. At the end of the subroutine, the Return Workspace Pointer (RTWP) restores these in reverse order. Using BLWP/RTWP, it is possible to nest subroutine calls despite the absence of a stack, however, the programmer needs to assign the appropriate register workspace explicitly.

The instruction set also contains a Branch and Link (BL) opcode that only saves PC to register 11 without changing WP. In this case, a branch instruction (B) using WR11 as the destination address can serve as the return opcode, but BL-type subroutines cannot be nested without the programmer taking actions to save the return address.

The TMS9900 supports an execute instruction "X" (eXecute). This instruction executes the instruction in a register. It can be used for debugging (as a breakpoint instruction), for creating indexed-opcode tables as used in byte-code interpreters and can also be used to perform a time critical I/O instruction during an interrupt. An example of its utility is shown in the code below where an interrupt is being serviced in a very encapsulated manner that would otherwise require many more instructions.

;***********************************

;

; THIS INTERRUPT SIMULATES DMA CONTROL

; ORGANISED AS FOLLOWS:

;

; R9 HOLDS CURRENT COMMAND, E.G.

; IOREAD(34B8H): STCR *R8+,BYTEWIDE ;BYTE WIDE FDC DATA READ

; IOWRITE(30B8H):LDCR *R8+,BYTEWIDE ;BYTE WIDE FDC DATA WRITE

; R8 HOLDS THE CURRENT DMA ADDRESS.

; R12 HOLDS THE CURRENT IO PORT - DATREG

;************************************

INTDRQ X R9 ;CAN BE EITHER READ or WRITE

RTWP

This common piece of code during the interrupt could be used by both I/O read and write commands. Similar methods could be employed in any debugging methods wanting to be used.

The TMS9900 also supports the eXtended OPeration (XOP) instruction. XOP is given a number in the range 0–15 as well as a source address. When invoked, the instruction will perform a context switch through one of sixteen vectors at predefined locations in memory. The XOP instruction also places the effective address of the source operand in register 11 of the new workspace. The context-saving feature of the XOP instruction can also be used as to implement inline debugging.[9]

XOP is less flexible than a BLWP, as the transfer vectors have to be at fixed locations, but allows one source operand to be directly addressed rather than passed in a register or otherwise.

XOP can be used to implement a system call facility. In TI's DX10 operating system, XOP 15 invokes a system call. A programmer might define an assembler macro, for example SVC, which invokes XOP 15. Another use of XOP was to implement instructions in software which might be handled by dedicated hardware in future versions of the 990 minicomputer series. An example of such actions can be shown in the code below where a CALL function is implemented using and XOP 6 Instruction. The beauty of this implementation of a CALL function using an XOP is that it is straightforward to add checks to determine if the stack overflowed, for example C R10,@2*R9(R13), where R9 points to the address of the stack limit.

; ;************************************************ ; CALL SUBROUTINE ; DEFINE XOP: DXOP CALL,6 ; CALLING METHOD: CALL @SUBROUTINE_ADDRESS ; R10 <=> STACK POINTER ;************************************************* ; ED32 C2AD 0014 XOP6: MOV @2*R10(R13),R10 ;GET STACK POINTER ED36 064A DECT R10 ;DECREMENT STACK POINTER ED38 C68E MOV R14,*R10 ;PUSH RETURN PC ONTO STACK ED3A C38B MOV R11,R14 ;MOVE EA INTO R14 (PC) FOR CALL ED3C CB4A 0014 MOV R10,@2*R10(R13) ;UPDATE STACK POINTER ED40 0380 RTWP ;WE ARE NOW USING THE ORIGINAL WP

In typical comparisons with the Intel 8086, the TMS9900 had smaller programs.[citation needed] Some[citation needed] disadvantages were the small address space and need for fast RAM.

Implementation

[edit]

The TMS9900 was implemented in an N-channel silicon gate MOS process,[7] which required +5 V, −5 V and +12 V power supplies and a four-phase (non-overlapping) clock with a maximum frequency of 3 MHz (333 ns cycle),[10] usually generated from a 48 MHz crystal using a TIM9904 (aka 74LS362) clock generator chip.

The shortest instructions require eight clock cycles or 2.7 μs to complete (assuming 0 external wait cycles), many others run between 10 and 14 cycles (3.3...4.7 μs); the longest-running instruction (DIV) can take up to 124 cycles (41.3 μs).[11]

Like the Motorola 68000, the chip was packaged in a (then-unusual) 64-pin, 0.9″ wide DIP. The comparatively large number of pins allowed for the 15-bit (word) address bus and 16-bit data bus to be brought out on dedicated pins without the use of multiplexing (unlike e.g. the Intel 8086 CPU), keeping external memory connections simple. Like Motorola, contrary to the convention used by many other manufacturers, TI labeled the most significant address and data lines "A0" and "D0," respectively. All internal data paths and the ALU are 16 bits wide.

The processor can be paused with the address bus tri-stated for external direct memory access (DMA). Memory accesses are always 16 bits wide, with the CPU automatically performing read-before-write operations for instructions with byte-wide accesses.

The hardware interrupt system supports a 4-bit interrupt priority input, which needed to be higher than the priority level stored in the status register (bits 12–15) in order for the interrupt request to be served. In addition, the /LOAD input provides a non-maskable interrupt facility with a dedicated vector.[12]

The TMS9900 CPU also contains a 16-bit shift register ("CRU") designed for interfacing with external shift registers, with dedicated instructions supporting access to fields of between 1 and 16 bits width out of a total of 4,096 addressable bits.

Parallel peripherals can be attached in memory-mapped fashion to the regular address and data bus.

Applications

[edit]

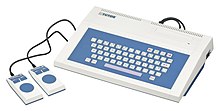

The TMS9900 was used in the TI-99/4 and TI-99/4A home computers. Unfortunately, to reduce the production costs, TI chose to use just 256 bytes (128 16-bit words) of the fast kind of RAM that the TMS9900 could access directly. The rest of the memory was 16 KB of 8-bit DRAM that was accessible only indirectly through the video display controller, which crippled the performance of these machines.

TI developed the TM990 series of computer modules, including CPU, memory, and I/O, which, when plugged into a card frame, could form a 16-bit minicomputer. These were typically used for process control.[13] A microprocessor trainer was released in the form of the TM990/189.[14]

In the late 1970s, John Walker and Dan Drake developed S100-bus cards based on the TMS9900 and a full software stack to go with it.[15][16] They later went on to be co-founders of Autodesk, which was in part based on software first developed for these TMS9900 based systems.[17]

TMS9900 Family Product Development

[edit]The next generation of the TMS9900 was the TMS9995, which provided "functional performance at speeds three times faster than any previous 9900 family processor,"[18] largely due to the inclusion of instruction prefetch technology. In the home computer arena, the TMS9995 only found use in the Tomy Tutor, as well as an obscure third-party computer-on-a-card upgrade for the TI-99/4A called the Geneve 9640, and a project printed in Electronics Today: the Powertran Cortex.[19] It was planned to be used in the TI-99/2 and TI-99/8 computer systems, but neither advanced past the prototype stage.

TI later developed the more powerful TMS99000 family of microprocessors, which was used as the CPU in the 990/10A minicomputer as a cost reduction. Ultimately, by the time the 990/10A made it to market, the end of the minicomputer era was already in sight.

The TMS99000 family includes two microprocessors,[2] the TMS99105A and the TMS99110A, which are identical except for the contents of on-chip macrostore ROM memory (macrostore memory contains added functions or instructions through emulation routines written in standard machine code). The on-chip ROM Macrostore in the TMS99110A microprocessor contains floating point instructions which are available as part of the machine language instruction set, while the baseline TMS99105A does not. Both chips can implement Macrostore instructions in an external ROM. A third member of the TMS99000 family, the TMS99120, was announced[20] but may never have been commercially produced. The on-chip ROM Macrostore in the TMS99120 was to contain run-time support routines for the PASCAL high-level language.

The instruction set for the TMS99000 family extends the 9900 instruction set while maintaining compatibility. The additional instructions include those for signed multiply and divide (first appearing in the TMS9995); long-word shift, add, and subtract; load status register; load workspace pointer; stack operations; multiprocessor support; and bit manipulation. Members of the family can access 256 KB of memory through code/data segmentation, and may use the TIM99610 memory mapper to address up to 16 MiB. The architecture contains many other advances over the TMS9900/TMS9995.[2]

Variants

[edit]| Model | Description |

|---|---|

| TI990/9 | Early multi-chip CPU for minicomputer systems, 1974 |

| TI990/10 | Multi-chip implementation for minicomputer systems, 1975 |

| TI990/12 | Multi-chip implementation, faster than 990/10 |

| TMS9900 | Single chip implementation, 1976, used in the TI-99/4(A) computer |

| TMS9940 | Microcontroller with 2KB ROM, 128B RAM, decrementer, CRU bus, 1979 |

| TMS9980 TMS9981 |

8-bit databus versions of TMS9900 |

| TMS9985 | TMS9940 with 8KB ROM, 256B RAM, and an 8-bit external bus, c. 1978 (never released) |

| TMS9989 | Improved 9980, used in military hardware |

| TMS9995 | Improved TMS9985-like, no ROM. Used in the TI-99/2 and TI-99/8 prototypes, as well as the Tomy Tutor and the Geneve 9640 computer-on-a-card for the TI-99/4A |

| TMS99105 | Baseline member of the TMS99000 microprocessor family |

| TMS99110 | TMS99000 family microprocessor with floating point instructions pre-programmed into the on-chip Macrostore ROM memory |

| TMS99120 | TMS99000 family microprocessor with run-time support routines for the PASCAL high-level language pre-programmed into the on-chip Macrostore ROM memory (microprocessor was announced but may never have been commercially produced) |

- Die photos

-

TMS9900

-

TMS9981

-

TMS9995

-

TMS99105A

Notes

[edit]- ^ Only the General Instrument CP1600 is close in release date.

References

[edit]- ^ 9900 Family Systems Design and Data Book (PDF). Texas Instruments. 1978. p. 2-3. ISBN 0-89512-026-7. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ a b c TMS99105A and TMS99110A 16-Bit Microprocessors Preliminary Data Manual (PDF). Texas Instruments Inc. 1982. p. 1.

- ^ TMS380 Adapter Chipset User's Guide. Texas Instruments. July 1986. pp. A-1 – A-22. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Whitworth, Ian (January 1979). "Review of microprocessor architecture". Microprocessors and Microsystems. 3 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1016/0141-9331(79)90088-7.

- ^ Guttag, Karl (1980-04-14). "99000 "Alpha" Performance Comparisons" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ Rhines, Walden C. (2017-06-22). "The Texas Instruments 99/4: World's First 16-Bit Home Computer". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- ^ a b TMS9900 Microprocessor Data Manual (PDF). Texas Instruments Inc. 1976. p. 3.

- ^ "DX10 Operating System Release 3.5 System Design Document" (PDF). Texas Instruments, Inc. 1982. p. 8.1.

- ^ "Using TMS 9000 XOP Instruction to implement a Debugging Function". GitHub. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ Texas Instruments 1976, p. 31.

- ^ Texas Instruments 1976, p. 28.

- ^ Texas Instruments 1976, p. 6.

- ^ "Stuart's TM 990 Series 16-Bit Microcomputer Modules". Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ^ "Programmable Calculators - Texas Instruments TM990/189". Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ^ "Marinchip Systems history". Retrieved 2024-08-25.

- ^ "Marinchip software". Retrieved 2024-08-25.

- ^ "Autocad history". Retrieved 2024-08-25.

- ^ TMS9995 marketing brochure (PDF). Texas Instruments Inc. 1981. p. 2.

- ^ "Powertran Cortex.com". Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ^ Microsystems Designers Handbook, 2nd Edition. Texas Instruments Limited. 1981. pp. 3–25 onwards.

External links

[edit]- TMS9900 manuals and references from Bitsavers