Edict of Gülhane

| Constitutional history of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Constitutional documents |

| Constitutions |

| Referendums |

| Constitutional Court |

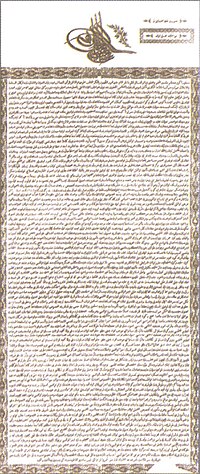

(The Ottoman Imperial Edict of Reorganization, proclaimed on 3 November 1839)

The Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif ("Supreme Edict of the Rosehouse"; French: Hatti-Chérif de Gulhané) or Tanzimât Fermânı ("Imperial Edict of Reorganization") was a proclamation by Ottoman Sultan Abdülmecid I in 1839 that launched the Tanzimât period of reforms and reorganization in the Ottoman Empire. The 125th anniversary of the edict was depicted on a former Turkish postcard stamp.[1]

The proclamation was issued at the behest of reformist Grand Vizier Mustafa Reşid Pasha. It promised reforms such as the abolition of tax farming, reform of conscription, and guarantee of rights to all Ottoman citizens regardless of religion or ethnic group.[2] The goal of the decree was to help modernize the empire militarily and socially so that it could compete with the Great Powers of Europe. It also was hoped the reforms would win over the disaffected parts of the empire, especially in the Ottoman controlled parts of Europe, which were largely Christian. At the time of the edict, millets (independent communal law-courts) had gained a large amount of religious autonomy within the empire, threatening the central government. This edict, along with the subsequent Imperial Reform Edict of 1856, was therefore an early step towards the empire's goal of Ottomanism, or a unified national and legal Ottoman identity.[3] It was published in the Tekvim-i Vekayi in Ottoman Turkish. In addition, it was published in Greek and French, the latter in Moniteur ottoman,[4] and François Alphonse Belin, a dragoman, created his own French version, published in the Journal Asiatique.[5]

The Edict of Gülhane did not enact any official legal changes but merely made royal promises to the empire's subjects, and they were never fully implemented due to Christian nationalism and resentment among Muslim populations in these areas.[6] At the end of the Crimean War, the Western powers pressured Turkey to undertake further reforms, mainly to deprive the Russians, with whom peace negotiations were then under way, of any further pretense for intervention in the internal affairs of the Ottoman Empire. The result of these pressures was the proclamation of the Hatt-ı Hümâyûn (Imperial Rescript) of 18 February 1856.[7]

Contents

[edit]While the Edict of Gülhane was more complex, it consisted mainly of three demands. The first was a guaranteed insurance of the security of life of every subject. The direction of thought here being that if a subject's life is endangered, he/she can become a danger to others and the sultan, since people do many things out of fear in order to protect their health. If there is an absence of security to fortune, everyone is insensible to the government and public good. The second proposed a regular system of assessing and levying taxes, troops, and duration of service. Subjects would be taxed a quota determined by their means and a reduced military term would lessen the blow that occurred to industries when the men were away. This collection of demands can be summed up under the title of governmental impositions on subjects. This new system of taxing ended tax-farming and introduced taxing based on means rather than a flat rate. Finally, the third dealt with reformation in the area of human rights and the justice system. The accused were to be granted public trials; individuals could possess and dispose of property in freedom; and punishments were to fit the deed regardless of rank. Reward by merit was presented in this edict. Additionally, the edict emancipated minorities, which granted them the opportunity to be conscripted. However, conscription could be avoided by minorities if they paid the Jizya. This allowed minorities of means to avoid conscription and it allowed for the military to mostly maintain its purity of minorities. Below are some of the important clauses in detail:[8]

Clauses

[edit]Some of the most important clauses are as follows:

- In the future, the case of every accused party will be tried publicly, in conformity with our divine law. Until a regular sentence has been pronounced, no one can put another to death, secretly or publicly, by poison or any other form of punishment.

- No one will be permitted to assail the honor of any one, whosoever he may be.

- Every person will enjoy the possession of his property of every nature, and dispose of it with the most perfect liberty, without any one being able to impede him. Thus, for example, the innocent heirs of a criminal will not be deprived of their legal rights, and the property of the criminal will not be confiscated.

- These imperial concessions extend to all our subjects, whatever religion or sect they may belong to; and they will enjoy them without any exception.

- Perfect security is, therefore, granted by us to the inhabitants of the empire, with regard to their life, their honor, and their fortune, as the sacred text of our law demands.

- With reference to the other points, as they must be regulated the concurrence of enlightened opinions, our Council of Justice (augmented by as many new members as may deemed necessary), to whom will be adjoined, on certain days which we shall appoint our Ministers and the Notables of the Empire, will meet for the purpose of establishing the fundamental laws on those points relating to the security of life and property, and the imposition of the taxes. Every one in these assemblies will state his ideas freely, and "give his advice freely."

- The laws relating to the regulations of the military service will be discussed by the Military Council, holding its meetings at the Place of the Serasker. As soon as a law is decided upon, it will be presented to us, and in order that it may be eternally valid and applicable will confirm it by our sanction, written above it with our imperial hand.

- As these present institutions are solely intended for the regeneration of religion, government, the nation, and the Empire, we to do nothing which may be opposed to them.

- In testimony of our promise we will, after having deposited these presents in the hall containing the glorious mantle of the Prophet, in the presence of all the ulama and the grandees of the Empire, make oath thereto in the name of God, and shall afterwards cause the oath to be taken by the ulama and grandees of the Empire.[7]

- After that, those from among the ulama or the grandees of the Empire, or any other person whatsoever who shall infringe these institutions, shall undergo, without respect of rank, position, and influence, the punishment corresponding to his crime, after the latter has been fully established. A penal code shall be compiled for that purpose.[7]

- As all the public servants of the Empire receive a suitable salary, and as the salaries of those whose duties have not up to the present time been sufficiently remunerated are to be fixed, a rigorous law shall be enacted against the traffic in favoritism and offices, which the divine law disapproves and which is one of the principal cause of the decay of the Empire.[7]

Changes and effects of the Edict of Gülhane

[edit]Some of the changes instituted by the Edict of Gülhane:[9]

- Reformed how the state related to its subjects; a more modern and unmediated relationship was developed. This helped the state run more efficiently.

- Began secularization of the state through which a new legal system of the state emerged. A state, criminal law, with less stringent rules for prosecution, was introduced to supplement the sharia, Sacred Law.

- Explosion in the bureaucracy which transformed the efficiency of the state. While in the old system bureaucrats had no salary and were paid fees by individuals, the changes brought on by the Edict of Gülhane established a state salary and gave them education.

See also

[edit]- Tanzimât Era (3 November 1839 – 22 November 1876)

- Hatt-ı Hümayun (18 February 1856)

- Confiscation in the Ottoman Empire

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Incorporates text from History of the Ottoman Turks (1878)

- Edward Shepherd Creasy, History of the Ottoman Turks; From the beginning of their empire to the present time, 2 vols., London, Richard Bentley (1854–6); (1878); Beirut, Khayats (1961).

- Abu-Manneh, Butrus (2015). "Gülhane, Edict of". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Postcard stamp cfile227.uf.daum.net

- ^ Cleveland, William L; Bunton, Martin (2009). A History of the Modern Middle East (4th ed.). Westview Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780813343747.

- ^ William L. Cleveland, A History of the Modern Middle East (Boulder: Westview Press, 2013), 77.

- ^ Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. pp. 21–51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Cited: p. 22 (PDF p. 24) - ^ Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. pp. 21–51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Cited: p. 23 (PDF p. 25) - ^ Cleveland 76–77.

- ^ a b c d Herbert J. Liebesny The law of the Near and Middle East readings, cases, and materials, Albany: State University of New York Press

- ^ Liebesny, Herbert (1975). The law of the Near and Middle East readings, cases, and materials. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 49–52.

- ^ Tanzimat

Further reading

[edit]- Greek version: D. Gkines and V. Mexas, Ελληνική Βιβλιογραφία 1800-1863 (Athens, Grapheion Dēmosieumatōn tēs Akadēmias Athēnōn, 1939-1957), vol. 1, no. 3165.

- Earlier French version: Moniteur Ottoman (27 November 1839, p. 2065).

External links

[edit]- The Rescript of Gülhane – Gülhane Hatt-ı Hümayunu (3 November 1839) - Translated into English, posted by the Atatürk Institute of Modern Turkish History of Boğaziçi University - The translator's name is not stated. Alternate link

- French version at the University of Perpignan