Terrorism and Communism

First German edition of Trotsky's Terrorismus und Kommunismus: Anti-Kautsky, published in Hamburg in August 1920. | |

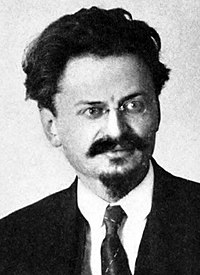

| Author | Leon Trotsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Терроризм и Коммунизм |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Political Philosophy, Marxism |

Publication date | 1920 |

| Publication place | Soviet Union |

| Media type | Print. |

| ISBN | 978-1844671786 |

Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky German: Terrorismus und Kommunismus: Anti-Kautsky; Russian: Терроризм и Коммунизм, Terrorizm i Kommunizm) is a book by Soviet Communist Party leader Leon Trotsky. First published in German in August 1920, the short book was written against a criticism of the Russian Revolution by prominent Marxist Karl Kautsky, who expressed his views on the errors of the Bolsheviks in two successive articles, Dictatorship of the Proletariat, published in 1918 in Vienna, Austria, followed by Terrorism and Communism, published in 1919.

Trotsky's book, the first English edition of which bore the title The Defense of Terrorism, dismisses the notion of parliamentary democracy to govern Soviet Russia and defends the use of force against opponents of the revolution by the dictatorship of the proletariat and working class masses.

History

[edit]Opening of the debate with Kautsky

[edit]

Early in August 1918, mere months after the November 1917 Bolshevik Revolution which brought the Communist Party to power in Russia, European Marxist Karl Kautsky published an oppositional political tract, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat, which charged the Bolsheviks with fomenting civil war due to their failure to uphold the norms of universal suffrage.[1] Kautsky's pamphlet, Die Diktatur des Proletariats (The Dictatorship of the Proletariat), asserted that the only way to control the growth of bureaucracy and militarism and to defend the rights of political dissidents was through parliamentary democracy based upon free elections and that V. I. Lenin and his political associates had blundered badly by departing from democratic practice in favor of a restricted electorate and the use of extra-parliamentary force.[2]

The Bolsheviks had sought broad international support from socialists around the world with a view to the achievement of worldwide revolution on a comparatively short timetable and Kautsky's sharply critical book was regarded by Bolshevik Party leader Lenin as a rank betrayal of the Russian Revolution and a grave threat to the revolutionary socialist mission.[3] Countering the public opposition by the world-famous Marxist Kautsky was regarded as pivotal.[3] Lenin was quick to respond to Kautsky's book with a bitter counterattack of his own, the short book The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, written in October and November 1918.[4]

Lenin railed against Kautsky's pamphlet as the "most lucid example of that utter and ignominious bankruptcy of the Second International about which honest socialists in all countries have been talking for a long time.[5] He charged that Kautsky had stripped Marxism of its "revolutionary living spirit" by his rejection of "revolutionary methods of struggle," thereby turning Karl Marx into "a common liberal."[6] Quoting Frederick Engels as an authority, Lenin contended that "proletarian revolution is impossible without the forcible destruction of the state machine and the substitution for it of a new one."[7] He minced no words in asserting as a "plain truth" that:

"Dictatorship is rule based directly upon force and unrestricted by any laws.

"The revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat is rule won and maintained by the use of violence by the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, rule that is unrestricted by any laws."[8]

Lenin rejected Kautsky's parliamentarian and legalistic interpretation of the ideas of Marx and Engels, contending that Kautsky knew well that the duo had "repeatedly spoke about the dictatorship of the proletariat, before and especially after the Paris Commune" of 1871, and that Kautsky had intentionally made a "monstrous distortion of Marxism" to bolster his own moderate political ideas.[9]

Kautsky's Terrorism and Communism (1919)

[edit]

Kautsky responded to Lenin's counterattack with a second pamphlet on the deteriorating political situation in Soviet Russia, a tract entitled Terrorismus und Kommunismus: Ein Beitrag zur Naturgeschichte der Revolution (Terrorism and Communism: A Contribution to the Natural History of the Revolution), completed in June 1919. With both Russia and Germany descending into chaos and civil war, Kautsky lamented "a world sinking under economic ruin and fratricidal murder," with Socialists fighting against Socialists in both countries "with similar cruelty to that practiced more than half a century ago by the Versailles butchers of the Commune."[10] Kautsky sought to draw a historical parallel between the ongoing Russian Revolution and Civil War with the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror which followed, culminating in the overthrow of the revolution by the military dictatorship of Napoleon Bonaparte.[11]

After expounding at length upon the dialectic of revolutionary violence in the historic French context, Kautsky turned his focus in the final section of Terrorism and Communism to "The Communists at Work."[12] Kautsky contended that World War I had brutalized the working class and forced it backwards "both morally and intellectually."[13] The social catastrophe of the war had brought about the Russian Revolution, Kautsky noted, leading to a collapse of the army and confiscation by the peasantry of landed estates for division into individual plots of land.[14] The Bolsheviks made calculated use of this elemental force, in Kautsky's view, "introducing anarchy in the country" in exchange for "a completely free hand in the towns in which they had already likewise won over the working classes."[15]

Mass expropriation of businesses followed, Kautsky charged, "without any attempt being made to discover whether their organisation on Socialist lines was possible."[16] Success depended upon a "well-disciplined and highly intelligent working class," Kautsky contended, but instead the war had sapped both intelligence and discipline from the workers, leaving only "the most ignorant and most undeveloped sections of the working class in the wildest excitement."[17] The result had been economic collapse.

A new system of brutality had emerged, in Kautsky's view:

"The bourgeoisie...appears in the Soviet Republic as a special human species, whose characteristics are ineradicable. Just as a negro remains a negro, a Mongolian a Mongolian, whatever his appearance and however he may dress; so a bourgeois remains a bourgeois, even if he becomes a beggar, or lives by his work....

"The bourgeoisie are compelled to work, but they have not the right to choose the work that they understand, and which best corresponds to their abilities. On the contrary, they are forced to carry on the most filthy and most objectionable kind of labour. In return they receive not increased rations, but the very lowest, which scarce suffice to appease their hunger. Their food rations equal only a quarter of those of the soldiers, and of the workingmen who are employed in the factories run by the Soviet Republic.... From all this we perceive not a sign of any attempt to place the proletariat on a higher level, to work out a 'new and higher form of life,' but merely the thirst for vengeance on the part of the proletariat in its most primitive form."[18]

Kautsky singled out Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky for specific criticism, upbraiding him for having seized power despite an admitted foreknowledge that the Russian working class and the revolutionary intelligentsia acting in its name had lacked "the necessary organisation, the necessary discipline, and the necessary historical education" to successfully establish a new economic and political regime.[19] Corruption had flourished in the aftermath and economic production had fallen to a point approaching complete collapse.[20]

Soon realizing the necessity of technical experts, Kautsky quotes Trotsky's admission that violence had been used to mercilessly destroy the organizations of "saboteurs" using coercion to transform "the saboteurs of yesterday into servants, into administrators, and technical managers, wherever the new regime demands it."[21] A new centralized administration had emerged, Kautsky contended, one in which "the absolutism of the old bureaucracy has come again to life in a new but...by no means improved form..."[22] New forms of profiteering, speculation, and corruption were emerging, Kautsky charged, so that "industrial capitalism, from being a private system, has now become a State capitalism."[23]

Kautsky concluded that ultimately the use of force and dictatorial methods would lead not to socialism, but to some new oppressive social system.[24] It was to this challenge that Leon Trotsky was to respond.

Trotsky's Terrorism and Communism (1920)

[edit]

Trotsky replied to Kautsky with a short book completed at the end of May 1920[25] and published in Hamburg in August by the publishing house of the Berlin-based West European Secretariat of the Communist International, Terrorismus und Kommunismus: Anti-Kautsky (Terrorism and Communism: Against Kautsky). The book was written, Trotsky remembered in 1935, inside a coach attached to his armored train during the tumultuous Polish Campaign of the Russian Civil War.[26] Trotsky retrospectively ascribed the book's harshness of tone to the time and place in which it was written.[26]

Trotsky recalled:

"So long as the class struggle flowed between the peaceful shores of parliamentarism, Kautsky, like thousands of others, indulged himself in the luxury of revolutionary criticism and bold perspectives: in practice these did not bind him to anything. But when the war and the after-war period brought the problems of revolution onto the field, Kautsky took up his position definitively on the other side of the barricade. Without breaking away from Marxist phraseology he made himself, instead of the champion of the proletarian revolution, the advocate of passivity of a crawling capitulation before Imperialism."[26]

In the view of Trotsky partisan Max Shachtman, Trotsky based his defense of the political tactics of the early Soviet Republic around two primary matters: the question of the revolutionary seizure of power and "the methods to be pursued by a socialist revolution in realizing socialism."[27] In Shachtman's view, Trotsky consistently argued that "special circumstances had made Russia ripe for a socialist revolution — the seizure of power" while at the same time the backwards agrarian nation was "not at all ripe for the establishment of a socialist society."[28] For this assistance from neighboring advanced industrial countries would be needed, and thus "European revolution was therefore regarded by all Bolsheviks as the only salvation of the Russian revolution."[28] This necessitated the rapid reorganization of European socialist parties on the Bolshevik model, according to Trotsky, marked by a splitting of the radical revolutionary socialist left wing of each from its parliamentarian and pacifist center and right.[28]

With respect to the socialist reorganization of the Russian economy, Trotsky rationalized and generalized from the ongoing experiences of War Communism, which featured "labor armies" directed to specific tasks in a quasi-military and more or less dictatorial way and he urged similar militarization of the workers based on the Russian experience.[29] Trotsky abjured this strategy as obsolete when Lenin pressed through the adoption of the New Economic Policy one year later, so the economic portion of Trotsky's book was later dismissed by Shachtman and other Trotsky followers as an anachronistic transmutation of "the expediencies and necessities of the civil war period into virtues and principles."[30]

Trotsky defended the use of terror by the Soviet government against the enemies of the Russian Revolution on utilitarian grounds. In the estimation of intellectual historian Baruch Knei-Paz, for Trotsky "the 'sacredness of human life' was not rejected in principle; but it was not...a value so absolute as to overshadow all other values."[24] Akin to the principle of self-defense, Trotsky argued in Terrorism and Communism that "the taking of human life was not only a necessary evil but an expedient act in time of revolution," in Knei-Paz's view.[24]

Trotsky justified the use of terror against the revolution's enemies by asserting that its use was directed and controlled by the working class itself rather than by a small circle of individuals in a political party.[31] The use of parliamentary democracy to maintain the socialist revolution was dismissed out of hand by Trotsky, and the demands for its use called mere "fetishism."[31] Parliamentarism was a cloak and a fiction employed to mask the rule of capitalist societies by vested economic interests, in Trotsky's view, whereas the dictatorship of the proletariat was able to make use of organized state power by the working class to crush its opponents and to pave the way for social transformation.[31]

The employment of political force, of violence and terror, was both essential and unavoidable during the revolutionary transition period from capitalism to socialism from Trotsky's perspective.[32] "The man who repudiates the dictatorship of the proletariat, repudiates the socialist revolution and digs the grave of socialism," Trotsky wrote.[33]

Chapter structure

[edit]Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky is divided into 9 chapters, bracketed by an introduction and an epilogue. The first section of the book, four chapters, deals with the practical political issues of holding power in Soviet Russia, with the so-called Dictatorship of the Proletariat in theory and practice, and with the nature of democracy and the use of force in the Russian context. A transitional middle section compares the Paris Commune with the Russian Revolution, emphasizing the political tactics and fate of each and upbraiding Kautsky for a lack of fidelity to the revolution, in which his failure is contrasted with the published writing of Karl Marx.

There follows two lengthy chapters on the specific political and economic policies of Soviet Russia during the ongoing period of War Communism, followed by a concluding polemic entitled "Karl Kautsky, His School and His Book."[34]

Publication history

[edit]Terrorism and Communism is a widely reprinted work of Leon Trotsky which has been translated into a host of languages. The Russian language original, Terrorizm i Kommunizm, saw print in 1920 and was excerpted in issues 10 and 11 of eponymous magazine of the Communist International.[35] German, French, Latvian, and Spanish editions followed later in 1920.[35] The book appeared the next year in translations in English, Bulgarian, Italian, Finnish, and Swedish.[35]

The year 1922 saw a first American edition of the booklet, as well as a Yiddish book and translation into Lithuanian through a magazine.[35] A Ukrainian edition followed in 1923.[35] In subsequent decades the book has seen print in Arabic, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Greek, Japanese, Serbo-Croatian, and Turkish, with multiple editions in some of the aforementioned languages.[35]

Legacy

[edit]Trotsky's Terrorism and Communism motivated another pamphlet by Kautsky, Von der Demokratie zur Staats-Sklaverei: Eine Auseinandersetzung mit Trotzki (From Democracy to State-Slavery: A Debate with Trotsky), completed in August 1921. The work was never translated into English. In it Kautsky noted the existence of drought and famine in Soviet Russia, a deadly situation which he asserted was exacerbated by a dysfunctional form of agrarian organization, transportation problems resulting the disruption of the national railway system which impeded the importation of food from non-famine areas, and bureaucratic paralysis.[36]

In this 1921 reprise, Kautsky returned to his theme that Trotsky and the Bolsheviks had been reckless in rushing to socialist revolution in a country ill-suited for the event economically or intellectually, intimating that economic collapse and famine were inevitable byproducts of this lack of preparation.

Political scientist Baruch Knei-Paz chronicled the political thought of Trotsky and noted that he was among the first of the Soviet figures to justify terror but this was done for the purpose of the revolution.[37] Knei-Paz stated that Trotsky viewed terror as a temporary albeit necessary measure against the old, Tsarist regime during the Civil War. Conversely, Knei-Paz contrasted this use of terror with the methods adopted by Stalin during the Great Purge which was taken to an unprecedented scale and became a permanent feature of the Soviet system.[38]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ John H. Kautsky, "Introduction," in Karl Kautsky, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat [1918]. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, 1964; pp. xv-xvii.

- ^ Kautsky, "Introduction," pp. xvii-xviii.

- ^ a b Max Shachtman, "Foreword to the New Edition" in Leon Trotsky, Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1961; pg. vii.

- ^ V.I. Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (1919), in V.I. Lenin Collected Works: Volume 28, July 1918-March 1919. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1965; pg. 227.

- ^ Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, pg. 229.

- ^ Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, pp. 229-231.

- ^ Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, pg. 237. Emphasis in original.

- ^ Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, pg. 236.

- ^ Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, pg. 233. Emphasis in original.

- ^ Karl Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism: A Contribution to the Natural History of Revolution [1920]. London: National Labour Press, 1921; pg. iv.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. iii.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pp. 158-234.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 158.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 162.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 163.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 166.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 167.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 171.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 173.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pp. 188-189.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 192.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 201.

- ^ Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism, pg. 202.

- ^ a b c Baruch Knei-Paz, The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1978; pg. 248.

- ^ Leon Trotsky, Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky [1920]. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1961; pg. 11.

- ^ a b c Leon Trotsky, "Introduction to the Second English Edition" [1935], in Trotsky, Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1961; pg. xxxvii.

- ^ Shachtman, "Foreword to the New Edition," pg. vii.

- ^ a b c Shachtman, "Foreword to the New Edition," pg. viii.

- ^ Shachtman, "Foreword to the New Edition," pg. xiv.

- ^ Shachtman, "Foreword to the New Edition," pg. xv.

- ^ a b c Knei-Paz, The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky, pg. 250.

- ^ Knei-Paz, The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky, pg. 251.

- ^ Cited without pagination in Knei-Paz, The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky, pg. 251.

- ^ Leon Trotsky, "Contents" to Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1961; pg. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f Louis Sinclair, Trotsky: A Bibliography: Volume 1. Aldershot, England: Scolar Press, 1989; pp. 248-249.

- ^ Karl Kautsky, Von der Demokratie zur Staats-Sklaverei: Eine Auseinandersetzung mit Trotzki. Berlin: Freiheit, 1921; pp. 5-6.

- ^ Knei-Paz, Baruch (1978). The social and political thought of Leon Trotsky. Oxford [Eng.]: Clarendon Press. pp. 406–407. ISBN 978-0-19-827233-5.

- ^ Knei-Paz, Baruch (1978). The social and political thought of Leon Trotsky. Oxford [Eng.]: Clarendon Press. pp. 406–407. ISBN 978-0-19-827233-5.

Further reading

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Karl Kautsky, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat (1918). H.J. Stenning, trans. London: National Labour Press, n.d. [c. 1925].

- V.I. Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (1919). From V.I. Lenin Collected Works, vol. 28. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974; pp. 227–325.

- Karl Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism: A Contribution to the Natural History of Revolution (1919). W.H. Kerridge, trans. London: National Labour Press, 1920.

- L. Trotsky, The Defense of Terrorism (Terrorism and Communism): A Reply to Karl Kautsky (1920). London: Labour Publishing Company and George Allen & Unwin, 1921.

- L. Trotzki, Terrorismus und Kommunismus: Anti-Kautsky. Hamburg: Westeuropäischen Sekretariat der Kommunistischen Internationale, 1920.

- Karl Radek, Proletarian Dictatorship and Terrorism (1920). Patrick Lavin, trans. Detroit, MI: Marxian Educational Society, n.d. [1921].

- Karl Kautsky, Von der Demokratie zur Staats-Sklaverei: Eine Auseinandersetzung mit Trotzki (From Democracy to State-Slavery: An Answer to Trotsky). Berlin: Freiheit, 1921. —In German.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Baruch Knei-Paz, The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Massimo L. Salvadori, Karl Kautsky and the Socialist Revolution, 1880–1938. Jon Rothschild, trans. London: New Left Books, 1979.

- Gary P. Steenson, Karl Kautsky, 1854–1938: Marxism in the Classical Years. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1978.

External links

[edit]- Terrorism and Communism by Leon Trotsky at the Marxists Internet Archive

- The Defence of Terrorism: Terrorism and Communism, a 1935 edition of the book in PDF format with a then-new introduction by the author