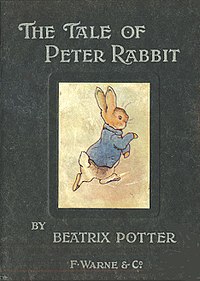

The Tale of Peter Rabbit

First edition cover | |

| Author | Beatrix Potter |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Beatrix Potter |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Publisher | Frederick Warne & Co. |

Publication date | October 1902 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| OCLC | 12533701 |

| Followed by | The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin |

The Tale of Peter Rabbit is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter that follows mischievous and disobedient young Peter Rabbit as he is chased about the garden of Mr. McGregor. He escapes and returns home to his mother who puts him to bed after dosing him with camomile tea. The tale was written for five-year-old Noel Moore, son of Potter's former governess Annie Moore, in 1893. It was revised and privately printed by Potter in 1901 after several publishers' rejections but was printed in a trade edition by Frederick Warne & Co. in 1902. The book was a success, and multiple reprints were issued in the years immediately following its debut. It has been translated into 36 languages[1] and with 45 million copies sold it is one of the best-selling books of all time.[2]

The book has generated considerable merchandise over the decades since its release for both children and adults with toys, dishes, foods, clothing, videos and other products made available. Potter was one of the first to be responsible for such merchandise when she patented a Peter Rabbit doll in 1903 and followed it almost immediately with a Peter Rabbit board game.

By making the hero of the tale a disobedient and rebellious little rabbit, Potter subverted her era's definition of the good child and the literary hero genre which typically followed the adventures of a brave, resourceful, young white male. Peter Rabbit appeared as a character in a 1971 ballet film, and the tale has been adapted to an animated television series.

Plot

Peter Rabbit, his sisters Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail, and his mother are anthropomorphic rabbits who dress in human clothing and generally walk upright on their hind legs, though they live in a rabbit hole under a fir-tree. Mother Rabbit has forbidden her children to enter the garden of Mr. McGregor: it was there that their father met his untimely end and became the ingredient of a pie. However, while Mrs. Rabbit is shopping and the girls are collecting blackberries, Peter sneaks into the garden. There, he gorges on vegetables until he gets sick, and is then chased about by Mr. McGregor. When Peter loses his jacket and his shoes, Mr. McGregor uses them to dress a scarecrow. After several close encounters with Mr. McGregor, Peter escapes the garden and returns to his mother exhausted and ill. She puts him to bed with a dose of camomile tea while his sisters (who have been good little bunnies) enjoy bread and milk and blackberries for supper. In a 1904 sequel, The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, Peter returns to McGregor's garden to retrieve his lost clothes.

Composition

Through the 1890s, Potter sent illustrated story letters to the children of her former governess, Annie Moore, and, in 1900, Moore, realizing the commercial potential of Potter's stories, suggested they be made into books. Potter embraced the suggestion, and, borrowing her complete correspondence (which had been carefully preserved by the Moore children), selected a letter written on 4 September 1893 to five-year-old Noel that featured a tale about a rabbit named Peter. Potter had owned a pet rabbit called Peter Piper.[3] The letter was too short to make a proper book so Potter expanded the tale and added black-and-white illustrations. Her revisions created a suspenseful tale, slowed the narrative pace, added intrigue and gave a greater sense of the passage of time. She copied the work into a hardcover exercise book with a frontispiece depicting an incident from the tale: Mrs. Rabbit dosing Peter with camomile tea after his ordeal.[4]

Publication history

Private publication

Potter's manuscript book was titled The Tale of Peter Rabbit and Mr. McGregor's Garden and sent to at least six publishers recommended by Potter's friends.[4] The manuscript was returned by all six including Frederick Warne & Co. which a decade earlier had expressed an interest in her artwork. Some publishers wanted a shorter tale, some a longer one and almost all wanted coloured illustrations which at that time were in demand and, through colour lithography, had become affordable.[5] The several rejections proved frustrating to Potter who knew exactly how her book should look (she had adopted the format and style of Helen Bannerman's Little Black Sambo) and how much it should cost.[6] She decided to publish the book herself, and, on 16 December 1901, the first 250 copies of her privately printed The Tale of Peter Rabbit were made available for distribution to family and friends.[7]

First commercial edition

In 1901, a Potter family friend and sometime poet, Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, set Potter's tale into didactic verse and delivered his version with her illustrations and a portion of her revised manuscript to Frederick Warne & Co., which had been among the original rejecters.[8] Warne editors declined Rawnsley's version but asked to see the complete Potter manuscript – their interest stimulated by the opportunity The Tale of Peter Rabbit offered the publisher to compete with the success of Helen Bannerman's wildly popular Little Black Sambo and other small format children's books then on the market. When Warne inquired about the lack of colour illustrations in the book, Potter tersely replied that rabbit-brown and green were uninteresting. Warne declined the book but opened the possibility for future publication.[9]

Warne wanted colour illustrations throughout the 'bunny book' (as the firm referred to the tale) and suggested cutting the illustrations from forty-two to thirty-two by indicating those to be eliminated.[9] Potter initially resisted the idea of colour illustrations – adhering to her preference for black-and-white pictures in the book – but then realized her stubborn stance was a mistake. She sent Warne several new colour illustrations and a copy of her privately printed edition which Warne then handed to their eminent picture book artist L. Leslie Brooke for his professional opinion. Brooke gave an enthusiastic endorsement to Potter's work. Fortuitously, his recommendation coincided with a sudden surge in the small picture book market.[10]

Meanwhile, Potter continued to distribute her privately printed edition to family and friends, with the celebrated creator of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, acquiring a copy for his children. When the first private printing of 250 copies was sold out, another 200 were prepared.[11] She noted in an inscription in one copy that her beloved pet rabbit Peter had died 26 January 1901 at the age of nine.[12]

Potter arrived at an agreement with Warne for an initial publication of 5,000 commercial copies priced at a very small sum with modest royalties for the author.[13] Negotiations dragged on into the following year with a contract finally signed in June 1902.[12] Potter was closely involved in the publication process of the trade edition of the tale – redrawing when necessary, adjusting the cadence, making minor adjustments to the prose and correcting punctuation. Even before the publication of the tale in early October 1902, the first 8,000 copies were sold out. By the year's end there were 28,000 copies in print; by the middle of 1903 there was a fifth printing with coloured endpapers; a sixth printing was produced within the month; and a year after the first commercial publication there were 56,470 copies in print.[14]

American copyright

Warne's New York office failed to register the copyright for The Tale of Peter Rabbit in the United States and unlicensed copies of the book (from which Potter would receive no royalties) began to appear in the spring of 1903. There was nothing that could be done to stop the flow of unlicensed copies.

The enormous financial loss to Potter only became evident over time, but the necessity of protecting her intellectual property hit home after the successful 1903 publication of The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin when her father returned from the Burlington Arcade in Mayfair at Christmas 1903 with a toy squirrel labelled Nutkin.[15]

Merchandising

The Tale of Peter Rabbit has generated a great deal of spin-off merchandise since its first commercial publication. Potter registered the patent for a Peter Rabbit doll on 28 December 1903, and the following year designed a Peter Rabbit board game (with the odds in Peter's favour). She set strict standards for those wanting to produce licensed merchandise such as stuffed toys, activity books, china tea sets, figurines, wallpapers, stationery, birthday and Christmas cards, and other merchandise from which she would receive royalties. The widespread popularity and success of Peter Rabbit merchandise caused Potter to proclaim in 1917, "All rabbits are called Peter now" – but qualified the statement for her American readers with "either Peter or Brer Rabbit."[16]

Considerable variants on the original format and version of The Tale of Peter Rabbit as well as spin-off merchandise have been made available over the decades. Variant versions include pop-up books, toy theatres, and lift-the-flap books. By 1998, modern technology had made available video versions of the tale, audio cassette retellings, a CD-ROM, a computer program, and Internet sites. Warne and its collaborators and competitors have produced activity books and a monthly educational magazine. Other materials for both children and adults have included puppets, mobiles, stuffed animals, crib toys, board games, dishes and china figurines, clocks and music boxes, hand-knitted sweaters and books of knitting patterns, bolts of fabric, baby and children's clothing, tea, jam, toothbrushes and soap, place-mats and coasters, wall stencils, stickers, paper towels, and even a cake was sold in British supermarkets. Major toy shops in the United States and Britain have had store sections earmarked exclusively for Potter-related toys and merchandise. In Britain's Lake District (where most of the tales are set) and in the Covent Garden area of London where Warne is located, many shops have been devoted entirely to the Potter-related merchandise.[17]

Pirating of The Tale of Peter Rabbit has flourished over the decades with products only loosely associated with the original. In 1916, American Louise A. Field cashed in on the popularity by writing books such as Peter Rabbit Goes to School or Peter Rabbit and His Ma, the illustrations of which showed him in his distinctive blue jacket.[18] An animated movie by Golden Films, The New Adventures of Peter Rabbit, gave Peter buck teeth, an American accent and a fourth sister Hopsy. This story had him and his city cousin Benny (i.e. Benjamin Bunny) pursuing a box which contains his sisters on the way to Zanzibar. Another video retelling of the tale cast Peter as a Christian preacher singing songs about God and Jesus with a group of children and vegetables.[17]

Critical commentaries

The text is often praised for its economy of words and the rhythmic drive of phrasing like the four-stress lines of alternating dactyls and iambic feet

But round the end of a cucumber frame,

whom should he meet but Mr. McGregor![19]

which is followed by the suspenseful pause of a page turned.

Biographer Linda Lear notes that Potter created a new form of animal fable in The Tale of Peter Rabbit — one in which anthropomorphic animals look and behave like real animals with real animal instincts, and a form of fable with anatomically correct illustrations drawn by a scientifically minded artist. She further states Peter Rabbit's nature is familiar to rabbit enthusiasts (and endorsed by those who are not) because "her portrayal speaks to some universal understanding of rabbity behaviour."[20] She describes the tale as a "perfect marriage of word and image" and "a triumph of fantasy and fact".[21]

Literary scholar, researcher, and critic Carole Scott in her essay “An Unusual Hero: Perspective and Point of View in The Tale of Peter Rabbit” (2002) views Potter's tale as a straight-forward, archetypal naughty boy story with an appropriate moral at tale's end,[22] but points out that Potter employed techniques to manipulate the reader into identifying with a hero who flouts adult wisdom, who causes his mother anxiety and grief by disobeying her, who commits trespass and theft, who evades paternalistic authority (Mr. McGregor), and who escapes all punishment save a passing stomach-ache as the result of his greediness.[23] She sees the major conflict in the tale as between the fixed order of society and the forces that seek to undermine it, between those who have and those who want, and between human civilization and animal nature.[24] Peter, she states, symbolizes “rebellion on all fronts.”[25]

Scott observes that the illustrations in The Tale of Peter Rabbit establish a sense of freedom with their irregular forms, variability in their shapes, their lack of borders and frames, and the degree of contextual detail they provide. The picture of Peter in the wheelbarrow she points out, is a rough rectangle with foreground, middle, and distant perspectives while the illustration of Peter jumping into the watering can lacks background and contextual setting. In the illustration of Mr. McGregor chasing Peter with a rake, the relationship between the two characters is established in spatial terms but provides no contextual detail. The continual shift of perspective, scope, and setting in the illustrations creates a fluctuating rather than a fixed viewpoint and is reflected in pages of full text and pages with but a few words.[26]

The reader cannot help but identify with rebellious little Peter and his plight as all the illustrations are presented from his low-to-the-ground view, most feature Peter in close-up and within touching distance, and Mr. McGregor is distanced from the reader by always being depicted on the far side of Peter. This identification with Peter heightens the reader's fear and tension, and interacts with the frequently distanced voice of the verbal narrative, sometimes with contradictory effects.[27] In the verbal narrative and the illustration for the moment when Mr. McGregor attempts to trap Peter under a garden sieve, for example, the verbal narrative presents the murderous intent of Mr. McGregor as a matter-of-fact, everyday occurrence while the illustration presents the desperate moment from the terrified view of a small animal about to die — a view that is reinforced by the birds that take flight to the left and the right, and Mr. McGregor's large, powerful, death-dealing hands.[28]

Potter is inconsistent in the use of contradictory effects in the word-picture interaction. For example, in the illustration of Peter standing by the locked door, the verbal narrative describes the scene without the flippancy evident in the moment of the sieve. Disempowerment and the inability to overcome obstacles is presented in the verbal narrative with objective matter-of-factness and the statement, “Peter began to cry” is offered without irony or attitude, thus drawing the reader closer to Peter’s emotions and plight. The illustration depicts an unclothed Peter standing upright against the door, one foot upon the other with a tear running from his eye. Without his clothes, Peter is only a small, wild animal but his tears, his emotions, and his human posture intensifies the reader’s identification with him. Here, verbal narrative and illustration work in harmony rather than in disharmony.[29]

Scott concludes her essay by noting Potter subverts not only her age’s expectations of what it takes to be a good child but subverts the hero genre with its young, objective, rational, resourceful white male who leaves the civilized world to brave obstacles and opponents in the wilderness, and, once his goal is achieved, returns home to grateful welcome and rewards.[30] Peter is quite unlike the traditional hero; he is small, emotionally driven, easily frightened, and a not very rational animal.[31] She suggests Potter’s tale has encouraged many generations of children to “self-indulgence, disobedience, transgression of social boundaries and ethics, and assertion of their wild, unpredictable nature against the constrictions of civilized living.”[32]

Adaptations

In 1971, Peter Rabbit appeared as a character in the ballet film The Tales of Beatrix Potter, and, in 1992, the tale was adapted to animation for the BBC anthology series, The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends. In 2006, Peter Rabbit was heavily referenced in a biopic about Beatrix Potter entitled Miss Potter.

References

- Footnotes

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 33

- ^ Worker's Press

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 35

- ^ a b Lear 2007, p. 142

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 143

- ^ Lear 2007, pp. 143–144

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 145

- ^ Lear 2007, pp. 145–146

- ^ a b Lear 2007, p. 146

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 147

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 150

- ^ a b Lear 2007, p. 149

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 148

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 152

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 164

- ^ Waller 2006, p. 343

- ^ a b Mackey 1998, pp. xxi–xxii

- ^ Hallinan 2002, p. 83

- ^ Ross 1996, p. 210

- ^ Lear 2007, p. 153

- ^ Lear 2007, pp. 154–155

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 19

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 20

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 23

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 27

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 21

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 22

- ^ Mackey 2002, pp. 22–23

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 26

- ^ Mackey 2002, pp. 28–29

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 28

- ^ Mackey 2002, p. 29

- Works cited

- Hallinan, Camilla (2002), The Ultimate Peter Rabbit: A Visual Guide to the World of Beatrix Potter, London (et al.): Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 0-7894-8538-9

- Lear, Linda (2007), Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-36934-7

- Mackey, Margaret (2002), Beatrix Potter's Peter Rabbit: A Children's Classic at 100, Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0-8108-4197-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mackey, Margaret (1998), The Case of Peter Rabbit, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-8153-3094-4

- Ross, Ramon Royal (1996), Storyteller: The Classic That Heralded America's Storytelling Revival, August House, ISBN 978-0874834512

- Waller, Philip (2006), Writers, Readers, and Reputations, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820677-1

- Worker's Press acknowledge Frederick Warne's intellectual property rights, Prnewswire.co.uk, 2003-07-10, retrieved 2009-08-31

External links

- The Tale of Peter Rabbit at Project Gutenberg

- The Tale of Peter Rabbit Audio Book at Project Gutenberg

- The Tale of Peter Rabbit Digital Book at The University of Iowa Libraries (Flash)

- World of Peter Rabbit: A website maintained by Potter's first publisher Frederick Warne & Co.