Thierry Ardisson

Thierry Ardisson | |

|---|---|

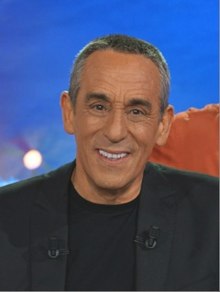

Thierry Ardisson on the set of Salut les Terriens ! February 20, 2014 (Plaine Saint-Denis) | |

| Born | 6 January 1949 Bourganeuf, Creuse, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation(s) | Television Host Television Producer Film Producer |

| Family | Béatrice Ardisson (divorced)[1] Audrey Crespo-Mara (since 2009) |

Thierry Ardisson (French pronunciation: [tiʁi aʁdisɔ̃], born 6 January 1949 in Bourganeuf, Creuse), is a French television producer and host [2] and a movie producer.[1]

Many of his shows have some of the longest run times on French television, such as Paris Dernière, Tout le monde en parle, and On a tout essayé. He is the author of several books, including best-sellers (Louis XX – Contre-enquête sur la Monarchie and Confessions d’un Babyboomer). In 2013, he released and produced the French movie Max.[3]

Biography

His parents were originally from Nice, in southern France. His father, a construction worker, settled for a short while in Bourganeuf (Creuse) where Thierry Ardisson was born.[4]

Early Career in Advertising and Journalism

In 1969, Thierry Ardisson moved to Paris to start a career in advertising. He was first hired at BBDO, then at TBWA, and later at Ted Bates, before founding his own agency, Business, in 1978 with Éric Bousquet and Henri Baché.[5]

While working for Business, he invented the 8-second TV ad format to allow low-budget advertisers to access television media.[6] As a copywriter, he wrote a number of memorable slogans for French consumers. Business also sold articles to French newspapers and magazines. As a writer, he contributed to the underground magazine, Façade.[5] Lady Diana's car that crashed in 1997 in Paris was formerly the propriety of Business agency[7].

In 1984, he was hired as the vice-director of publications for the Hachette-Filipacchi press group. His editorial decisions were considered too provocative and led to his discharge.[5] But in 1992, he worked a new partnership with Hachette-Filipacchi and launched the magazine Entrevue.[1] He sold his shares of the company back to Hachette-Filipacchi in 1995.[8]

In 1998, he launched the consumer magazine J’économise (“I save up”) which peaked at 420,000 prints.[9]

Career in Television

In 1980, in the course of the interviews that his agency Business conducted for French newspapers and magazines, Thierry Ardisson interviewed French tennis player Yannick Noah who admitted to smoking hashish and that tennis players regularly took amphetamines before the games, a scandal that led to his first appearance on television.[10]

In 1985, he adapted his press interviews (called Descente de police) for the French TV network TF1, but the concept – too brutal and provocative – got censored by French media authorities. TF1 kept him to host the show Scoop à la une.[11] He then coproduced the show À la folie pas du tout from 1986 to 1987, hosted by later-famous news anchor host, Patrick Poivre-d’Arvor.[12]

In 1987, he sold his shares of his advertising agency Business and founded the TV production company Ardisson & Lumières.

From 1987 to 1988, he produced for the TV network La Cinq the show Face à Face, hosted by Guillaume Durand, as well as Bains de minuit, a late-night show shot in the then-trendy night club Les Bains Douches that he hosted.[13] From 1988 and 1990, he hosted the show Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches, shot in the parisian theater Le Palace and aired on French TV channel Antenne 2.[14] For this show, he created the concept of “formatted interviews” such as “interview first time,” “self-interview” or “stupid questions.” During the same period, he coproduced the show Stars à la Barre.[15]

Afterwards, he hosted the show Télé Zèbre, which introduced two famous French comedians: Yvan Le Bolloc'h and Bruno Solo.[16] From 1991 to 1992, he hosted the late-night game show Double jeu with Laurent Baffie, a show that was also considered too provocative and was canceled by TV network Antenne 2 in early 1993.[17] From 1992 to 1994, he produced the shows Frou-Frou,[18] Graines de Stars[19] and Flashback.

In 1995, he produced and hosted Paris Dernière on the French cable channel Paris Première.[20] In 1997, he hosted Rive droite / Rive gauche with Frédéric Beigbeder, Élisabeth Quin and Philippe Tesson.[21]

In 1998, he joined France 2 (formerly Antenne 2) to host Tout le monde en parle each Saturday at prime time, alongside Laurent Ruquier, Linda Hardy, Kad et Olivier and Laurent Baffie.[22]

From 2003 to June 2007, he hosted 93, faubourg Saint-Honoré on Paris Première, a dinner in his parisian apartment with a panel of various celebrities.[23]

At the end of the 2005–2006 season, Thierry Ardisson left France 2 after a contractual disagreement (regarding his involvement with the competing TV channel, Paris Première) and joined the French semi-private TV network Canal+.[24] Since November 2006, he has produced and hosted the show Salut les Terriens ! every Saturday night at access prime time.[25] The show attracted 750K viewers the first year it ran.[26]

Starting in December 2010, he hosted the show Tout le monde en a parlé for the TV channel Jimmy. The show aired three seasons.[27]

In Octobre 2014, the audience of the show Salut les Terriens ! reached 1,4 million viewers, which made it the most popular show for Canal+.[26]

Career in Film

In 2005, he created the Ardimages group to produce feature films and television series.[28]

In 2012, he produced his first feature film, Max, directed by Stephanie Murat with Joey Starr and Mathilde Seigner, and distributed by Warner Bros. [29][30]

In 2013, he began producing a second feature film, The Gift, directed by Jean-Paul Rouve and starred Michel Blanc, Annie Cordy, Chantal Lauby and Audrey Lamy[31].

Career in Radio

On August 29, 2014, Thierry Ardisson joined Laurent Ruquier’s "Les Grosses Têtes" on RTL.[32]

Personal life

In 2014 Ardisson married French journalist Audrey Crespo-Mara.[33]

Broadcasts

- 1985 : Descente de police on TF1

- 1985–1986 : Scoop à la une on TF1

- 1987–1988 : Bains de minuit on La Cinq [34]

- 1988–1990 : Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches on Antenne 2

- 1990–1991 : Télé zèbre on Antenne 2

- 1991–1992 : Double jeu on Antenne 2

- été 1992 : Le bar de la plage on France 2

- 1993 : Ardimat on France 2

- 1994 : Autant en emporte le temps on France 2

- 1994 : Long courrier on France 2

- 1995–1997 : Paris Dernière on Paris Première

- 1997–2004 : Rive droite / Rive gauche on Paris Première

- 1998–2006 : Tout le monde en parle on France 2

- 2001–2002 : Ça s'en va et ça revient on France 2

- 2003–2004 : Opinion publique on France 2

- 2003–2007 : 93, faubourg Saint-Honoré on Paris Première

- 2010–2014 : Happy Hour on Canal+

- Since 2006 : Salut les Terriens ! on Canal+

- Since 2010 : Tout le monde en a parlé on Jimmy

- Special Broadcasts

- June 1990 : Rolling Stones : les jumeaux impossibles on Antenne 2

- January 1993 : Cœur d'Ardishow on France 2

- 2001 : La Nuit Gainsbourg on France 2

- October 2002 : Bedos/Ardisson : on aura tout vu ! on France 2

- 2002 : Le père noël n'est pas une ordure on France 2

- June 2002 : Spéciale Maillan-Poiret on France 2

- April 2003 : Le Grand Blind Test on France 2

- 2004 : 60e anniversaire du Débarquement (avec Michel Drucker) on France 2

- April and May 2005 : Le Plus Grand Français de tous les temps on France 2

- April 2008 : Ardisson : 20 ans d'antenne on Jimmy

Bibliography

Novels

- Thierry Ardisson, Cinemoi, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, coll. « Cadre Rouge », October 1, 1973 (ISBN 2020012243)

- Thierry Ardisson, La Bilbe, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1975 (ISBN 9782020042253)

- Thierry Ardisson, Rive droite, Paris, Éditions Albin Michel, February 11, 1983, 216 p. (ISBN 2226016848)

- Thierry Ardisson, Louis XX – Contre-enquête sur la Monarchie 1986 (ISBN 2855653347), sold over 100,000 copies.[35]

- Thierry Ardisson, Pondichéry, Éditions Albin Michel, 1994 (ISBN 2226061177),

- Thierry Ardisson and Philippe Kieffer, Confessions d'un Babyboomer, 2006 (ISBN 2744173185) sold over 100,000 copies.[36]

Essays

- Thierry Ardisson, Louis XX, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, coll. « Folio », 11 mars 1988, 249 p. (ISBN 2070379124)

- Thierry Ardisson, Pondichéry, 1994 (ISBN 2226061177)

- Thierry Ardisson, Cyril Drouet & Joseph Vebret, Dictionnaire des provocateurs, Paris, Plon, 25 novembre 2010 (ISBN 2259212131)

- Thierry Ardisson (collectif), Rock Critics, Paris, Don Quichotte, 6 mai 2010, 304 p. (ISBN 9782359490169)

- Thierry Ardisson, Le Petit livre blanc. Pourquoi je suis monarchiste, Paris, Plon, 4 octobre 2012 (ISBN 978-2259217484)

Autobiography

- Thierry Ardisson, Les années provoc, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, coll. « Docs Témoignage », 1er novembre 1998, 347 p. (ISBN 2080676350)

- Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer, Confessions d'un babyboomer, Paris, Flammarion, 15 octobre 2004, 358 p. (ISBN 208068583X)

Television

- Thierry Ardisson & Laurent Baffie, Tu l'as dit Baffie ! Concentré de vannes, Paris, Le Cherche midi, coll. « Le Sens de l'humour », April 21, 2005 (ISBN 2749103851)

- Thierry Ardisson & Jean-Luc Maître, Descentes de police, Paris, Love Me Tender/Business Multimedia, 1984, 139 p. (ISBN 2749101441)

- Thierry Ardisson (collectif), Paris dernière. Paris la nuit et sa bande son, Paris, M6 Éditions, November 10, 2010, 320 p. (ISBN 2915127808)

- Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer, Tout le monde en a parlé, Paris, Flammarion, 2012, 360 p. (ISBN 9782081221260)

- Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer, Magnéto Serge !, Paris, Flammarion, 2013, 300 p. (ISBN 9782081280298)

Contributions

- Thierry Ardisson (collectif), Dix ans pour rien ? Les années 80, Paris, Éditions du Rocher, coll. « Lettre recommandée », 1990 (ISBN 2268009114)

- Thierry Ardisson (postface), Peut-on penser à la télévision ? La Culture sur un plateau, Paris, Éditions Le Bord de l'eau/INA, coll. « Penser les médias », 2010, 290 p. (ISBN 2356870644)

Videography

- Thierry Ardisson, Paris interdit. Découvrez les endroits les plus interdits de Paris, documentaire, 1997. (VHS)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Double Jeu, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSOM)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Lunettes Noires pour Nuits Blanches, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSO2)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Tout le monde en parle, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSOW)

- Thierry Ardisson, La Boite noire de l'homme en noir, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSNS)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Paris Première, M6 Vidéo, 2011. (ASIN B005JYUWSW)

- Collectif, Où va la création audiovisuelle, BnF/Ina, 201168.,[37]

Music

- Instant Sex. Le Disque souvenir de l'émission culte Double Jeu de Thierry Ardisson, vinyle, 1993.

- La Musique de Tout le monde en parle, compilation, Naïve, 2002.

He is cited in a song by Renaud, Les Bobos : « Ardisson et son pote Marco » (référence à Marc-Olivier Fogiel).

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Thierry Ardisson Biography". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Damien, Mercereau. "Thierry Ardisson enfonce Jean-Luc Delarue". Le Figaro. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Max (I) (2012)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer 2004, p. 29

- ^ a b c Technikart. "Ex-fan des eighties". Technikart. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Emmanuel, Berretta. "Thierry Ardisson, de A à Zèbre". Le Point. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Daily Mail. "Diana's Paris crash car 'was a rebuilt wreck': Mercedes pool car provided by hotel on night she died 'had been stolen and driven into the ground earlier in the year' and was 'hugely dangerous above 37mph'". Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Garrigos, Raphaël. "De Warhol à Laetitia Casta". Liberation. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Fontaine, Gilles. "" J'économise " cartonne". L'Expansion. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Plateau Thierry Ardisson". ina.fr. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Scoop à la Une (1985–1986)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "À la folie, pas du tout (1987)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Bains de minuit (1987–1988)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches (1988–1990)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Stars à la barre (1988–1990)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Télé-Zèbre (1990– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Quand Thierry Ardisson passe aux aveux". Le Point. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Frou-Frou (1992–1994)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Graines de star (1996– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Paris dernière (1999– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Rive droite – rive gauche (1997– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Tout le monde en parle (1998–2006)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "93 Faubourg Saint-Honoré (2003– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Garrigos, Raphaël; Roberts, Isabelle. "C'est un miracle que tu fusilles". Liberation fr. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Salut les Terriens (2006– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b Kessous, Mustapha. "Thierry Ardisson : " Quand vous êtes créateur en France, vous vous demandez à quoi vous servez " En savoir plus sur http://www.lemonde.fr/televisions-radio/article/2014/10/24/tv-quo-entretien-ardisson-4-pages-quand-vous-etes-createur-en-france-vous-vous-demandez-a-quoi-vous-servez_4512178_1655027.html#ZsPZ0StCtI1P55j8.99". Le Monde. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Ardisson animera "Tout le monde en a parlé" sur Jimmy". jeanmarcmorandini. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Gonzales, Paule. "Thierry Ardisson se lance dans le cinéma". Le Figaro. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson coproduit son premier film". Le Figaro. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Bruno, Maxime. "Thierry Ardisson produit son premier film, Max". L'Express. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Annie Cordy et Audrey Lamy plongent dans les Souvenirs de Jean-Paul Rouve". PurePeople.com. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Franz-Olivier Giesbert et Thierry Ardisson rejoignent Laurent Ruquier". RTL.fr. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ http://www.femmeactuelle.fr/actu/news-actu/thierry-ardisson-marie-avec-audrey-crespo-mara-17938

- ^ "Bains de minuit". Toutelatele.com. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Perrin, Élisabeth. "La télé refait le D-Day". TV Mag. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Revel, Renaud. "Sinistrose". L'Express. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Template:Vid Broadcast Tout le monde en parle, 8