Thomas Henry Flewett

Thomas Henry Flewett | |

|---|---|

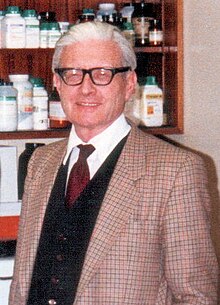

In his laboratory at East Birmingham (now Heartlands) Hospital in 1984 | |

| Born | 29 June 1922 Shimla, India |

| Died | 12 December 2006 (aged 84) Solihull, United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | Queen's University Belfast |

| Known for | Rotaviruses |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Virology |

| Institutions | Regional Virus Laboratory, Birmingham |

| Signature | |

| |

Thomas Henry Flewett, MD, FRCPath, FRCP (29 June 1922 – 12 December 2006) was a founder member (and subsequently Fellow) of the Royal College of Pathologists and was elected (by distinction) a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1978. He was chairman of the World Health Organization (WHO) Steering Committee on Viral Diarrhoeal Diseases, 1990–3, and a member until 1996. His laboratory in Birmingham was a World Health Organization Reference and Research Centre for Rotavirus Infections from 1980 until his retirement in 1987. He was an external examiner, visiting lecturer, and scientific journal editor. He was a member of the board of the Public Health Laboratory Service (now UK Health Security Agency) from 1977 to 1983 and was chairman of the Public Health Laboratory Service's Committee on Electron Microscopy from 1977 to 1987.

Flewett received his medical education at Queen's University, Belfast, where he graduated with honours at the end of the World War II in 1945. In 1951 he married June Evelyn Hall who predeceased him. He was survived by their two daughters, Janet Anne and Judy Elizabeth. Another daughter, Pamela Margaret Jane, died in infancy.[1]

Childhood

[edit]Flewett was born in Shimla India, where his father, William Edward Flewett (born 1894[2]) a graduate of Oxford University, was a member of the Imperial Forestry Service,[3] that, in 1966, became the Indian Forest Service of the Indian Civil Service.[4] In 1915, his father joined the Indian Reserve Army, as required by law, becoming a Second Lieutenant in July 1916.[5][6] He was transferred to Lahore in 1924.[3] Thomas Flewett was educated at Campbell College in Belfast.[7]

Early years 1945–1956

[edit]Flewett studied medicine at Queen's University Belfast, where he graduated with honours in 1945. He worked at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast and, from 1946 to 1948, was a demonstrator in bacteriology and pathology at Queen's University. His scientific interest in viruses began with his membership of the scientific staff of the National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill, where he spent three years between 1948 and 1951 researching common cold viruses and exploring the effect of influenza viruses on cells in culture. This led to his first use of electron microscopy, in which he became a leading authority. In 1951 he moved as lecturer in bacteriology to Leeds University, where he was involved in the 1953 smallpox outbreak.[8] This experience proved invaluable twenty-five years later when a laboratory-associated case of smallpox at the Medical School of the University of Birmingham, UK, led to the death of Janet Parker.[9] In 1951 he married June Evelyn Hall who bore him three daughters.[4]

Regional Virus Laboratory, Birmingham, England 1956–1987

[edit]In 1956 Flewett was appointed consultant virologist to East Birmingham Hospital (now Heartlands Hospital) , where he established one of the first virus laboratories in England. His laboratory was close to an infectious diseases unit and this enabled him to provide confirmation of the clinical diagnosis of diseases that included poliomyelitis, diarrhoea, smallpox and AIDS. He was a member of the hospital's senior management team and helped to establish the regional immunology laboratory there.[7]

Flewett's interests included influenza, coxsackie A and coxsackie B viruses, the major and minor variants of smallpox virus, and hepatitis B virus. Although he discovered the cause of hand, foot and mouth disease,[10] the work that gained him an international reputation began in the early 1970s with the discovery of viruses causing diarrhoea, particularly in infants and young children. Flewett named one of the then most frequent causes of death in infants in tropical countries, rotaviruses.[7]

Norwalk virus had been discovered by Albert Kapikian using immune electron microscopy[11] and Ruth Bishop and colleagues had seen different particles that they thought were viruses in gut biopsies by thin section electron microscopy.[12] But the preparation of thin sections was too cumbersome for routine use, and Flewett and his co-workers showed that these viruses could be seen by electron microscopy directly in faeces.[13] Flewett and his colleagues in his Birmingham laboratory had observed these viruses in the faeces of sick children before the publication of Ruth Bishop's paper but they failed to realise that they were the cause of the infection. The virus particles have a wheel-shaped appearance by electron microscopy, and it was Flewett who gave them the name "rotavirus," by which they have been known since.[14] Flewett wrote: 'At the South Wiltshire Virology Society I met Gerald Woode, then at Compton, in late 1973. He described a virus causing diarrhoea in calves. I realized we had much the same in children. We found his virus and ours were related – something new. We called them rotaviruses'[14][15]

His original idea was to suggest the name "urbivirus" because of the structural similarity of rotavirus to orbivirus. Ruth Bishop, who was the first to describe rotaviruses as a cause of gastroenteritis had suggested "duovirus" because these viruses replicate in the duodenum and, at the time, were thought to have a double protein outer coat. The early research papers from the 1970s use both names.[16]

Flewett did much collaborative work on rotaviruses with others to establish the varieties of rotavirus which infect the young of virtually every species of animal.[17] His research group were the first to describe the different serotypes of rotavirus.[18] This work was important to the development of a rotavirus vaccine. He also identified two new species of adenoviruses (later called types 40 and 41), as well as confirming the presence of caliciviruses, astroviruses, and faecal coronaviruses. He, along with H.G. Pereira also discovered picobirnaviruses,[19][20] and with other colleagues first described human torovirus.[21]

Birmingham smallpox tragedy

[edit]

Janet Parker was the last person to die from smallpox. The diagnosis was made by Professor A. Geddes at East Birmingham Hospital where she had been admitted.[22] Before the diagnosis had been confirmed, a member of Flewett's laboratory had collected fluid from Janet Parker's vesicles and taken it across the grounds of the hospital for examination in the virus laboratory. Flewett ordered his staff to fumigate the laboratory with formaldehyde. The ward in which Janet Parker had been initially cared for was also fumigated. The building housing wards 31 and 32 were later demolished. Two members of Flewett's team were subsequently quarantined but apart from Janet Parker's mother, no further cases of smallpox occurred. This tragedy led to the suicide of Professor Henry Bedson.[23]

WHO Reference and Research Laboratory 1980–1987

[edit]

Flewett's work on rotaviruses brought him international recognition both as a virologist and an electron microscopist. He was one of the first western virologists to be invited to the People's Republic of China (in 1983) to lecture. He was a judge for the King Faisal International Prize in 1983, which was awarded to Professor John S. Fordtran, Dr William B. Greenough III and Professor Michael Field, for their work on oral rehydration therapy in reducing mortality and morbidity due to cholera and other acute infectious diarrhoeal diseases.[24]

During these years he travelled widely as a World Health Organization consultant to most countries in which childhood diarrhoea is a major problem. He established The WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Rotaviruses, (known as The WHO Lab), at his laboratory which was supported by The World Health Organization from 1980 until his retirement in 1987. This laboratory was formerly a small tuberculosis bacteriology laboratory.

As well as continuing with basic research on the viruses that cause gastroenteritis, his laboratory produced reagents for the laboratory diagnosis of rotavirus infections based on monoclonal antibodies developed by his research team.[25] These reagents were sent regularly to numerous hospital laboratories throughout the developing world. The WHO laboratory attracted many visiting scientists from many countries and his team of research scientists contributed to the development of a vaccine against rotavirus infections.[26] His laboratory was active in the search for other, undiscovered causes of viral infections which Flewett called "the diagnostic gap", because many causes of gastroenteritis are still unknown.[27]

Legacy

[edit]Flewett was educated at a time when very little was known about viruses and viral illness and when there were no laboratory tests to aid or confirm a diagnosis. Flewett was a pioneer—today diagnostic virology laboratories, like the one he established in 1956, can be found throughout the world. Flewett published over 120 scientific and medical articles and papers.[7] Following the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine, worldwide the incidence of deaths of children caused by rotavirus has fallen from around 500,000 each year in 2000, to around 200,000 in 2013.[28] As more countries use the vaccine, the incidence is decreasing.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ Thomas Henry Flewett Royal College of Physicians

- ^ British Library

- ^ a b P. S. Sharma, The Indian Forester, Vol 50, p. xxii, (1924)

- ^ a b Lives of the Fellows, Royal College of Physicians

- ^ Army Headquarters, India (3 February 2012). Indian Army List January 1919 — Volume 1. Andrews UK Limited. p. 513. ISBN 978-1-78150-255-6.

- ^ The London Gazette, 14 July, 1916

- ^ a b c d Madeley, D. (2007). "Obituary Thomas Henry Flewett". BMJ. 334 (7596): 753. doi:10.1136/bmj.39167.721898.FA. PMC 1847847.

- ^ Flewett TH. The clinical and laboratory diagnosis of variola minor (alastrim). Br J Clin Pract. 1970 Sep;24(9):397–402.

- ^ Kotar, Gessler, S.L., J.E. (2013). Smallpox: A History. McFarland. p. 375. ISBN 9780786493272.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Flewett TH, Warin RP, Clarke SK. 'Hand, foot, and mouth disease' associated with Coxsackie A5 virus. J Clin Pathol. 1963 Jan;16:53-5.

- ^ Kapikian, AZ; Wyatt, RG; Dolin, R; Thornhill, TS; Kalica, AR; Chanock, RM (November 1972). "Visualization by immune electron microscopy of a 27-nm particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis". J Virol. 10 (5): 1075–81. doi:10.1128/JVI.10.5.1075-1081.1972. PMC 356579. PMID 4117963.

- ^ Bishop, RF; Davidson, GP; Holmes, IH; Ruck, BJ (December 1973). "Virus particles in epithelial cells of duodenal mucosa from children with acute non-bacterial gastroenteritis". Lancet. 2 (7841): 1281–3. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(73)92867-5. PMID 4127639.

- ^ Booss, John.; August, Marilyn J. (2013). To catch a virus. Washington, DC: ASM Press. pp. 218–222. ISBN 978-1-55581-507-3.

- ^ a b Flewett, TH; Woode, GN (1978). "The rotaviruses". Arch Virol. 57 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1007/bf01315633. PMC 7087197. PMID 77663.

- ^ Letter to Dr Tilli Tansey, 8 February 1998. Woode was at the Institute for Research on Animal Diseases, Compton, Newbury, Berks. See Flewett T H, Bryden A S, Davies H, Woode G N, Bridger J C, Derrick J M. (1974) Relation between viruses from acute gastroenteritis of children and newborn calves. Lancet ii: 61–63.

- ^ Wyatt GB, Hocking B, Bishop R, Wyatt JL. Duovirus infection as a cause of infantile gastro-enteritis in Port Moresby. P N G Med J. 1976 Sep;19(3):134-6.

- ^ Flewett, T H.; Bryden, A S.; Davies, H A. (1975). "Virus diarrhoea in foals and other animals". Vet. Rec. 96: 477.

- ^ Beards, GM; Pilfold, JN; Thouless, ME; Flewett, TH (1980). "Rotavirus serotypes by serum neutralisation". J Med Virol. 5 (3): 231–7. doi:10.1002/jmv.1890050307. PMID 6262451. S2CID 36204452.

- ^ Treanor, J. J., R. Dolin. 2005. Astroviruses and picobirnaviruses. 2201–2203, in: Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and practice of infectious diseases (6th Ed.). Mandell G. L., Bennett J. E., Dolin R. (Editors). Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.

- ^ Pereira, H. G.; Flewett, T. H.; Candeias, J. A.; Barth, O. M. (1988). "A virus with a bisegmented double-stranded RNA genome in rat (Oryzomys nigripes) intestines". Journal of General Virology. 69 (11): 2749–2754. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-69-11-2749. PMID 3053986.

- ^ Beards, G. M.; Brown, D.W.G.; Green, J.; Flewett, T. H. (1986). "Preliminary Characterisation of Torovirus-Like Particles of Humans: Comparison With Berne Virus of Horses and Breda Virus of Calves". Journal of Medical Virology. 20 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1002/jmv.1890200109. PMC 7166937. PMID 3093635.

- ^ S.L. Kotar; J.E. Gessler (12 April 2013). Smallpox: A History. McFarland. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-7864-9327-2.

- ^ [1] The Shooter Report

- ^ Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online, Issue no.16 – February 1984

- ^ Beards GM, Campbell AD, Cottrell NR, Peiris JS, Rees N, Sanders RC, Shirley JA, Wood HC, Flewett TH. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays based on polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies for rotavirus detection" J Clin Microbiol. 1984 Feb;19(2):248-54.

- ^ Vesikari T, Isolauri E, Delem A, d'Hondt E, Andre FE, Beards GM, Flewett TH. Clinical efficacy of the RIT 4237 live attenuated bovine rotavirus vaccine in infants vaccinated before a rotavirus epidemic" J Pediatr 1985 Aug;107(2):189-94.

- ^ J Med Virol. 2003 Jun;70(2):258-62.Infantile viral gastroenteritis: on the way to closing the diagnostic gap. Simpson R, Aliyu S, Iturriza-Gomara M, Desselberger U, Gray J.Clinical Microbiology and Public Health Laboratory, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- ^ Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Parashar UD (2016). "Global, Regional, and National Estimates of Rotavirus Mortality in Children <5 Years of Age, 2000-2013". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 62 (Suppl 2): S96–S105. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1013. PMID 27059362.

- ^ Wang, Haidong; Naghavi, Mohsen; Allen, Christine; Barber, Ryan M.; Bhutta, Zulfiqar A.; Carter, Austin; Casey, Daniel C.; Charlson, Fiona J.; Chen, Alan Zian; Coates, Matthew M.; Coggeshall, Megan; Dandona, Lalit; Dicker, Daniel J.; Erskine, Holly E.; Ferrari, Alize J.; Fitzmaurice, Christina; Foreman, Kyle; Forouzanfar, Mohammad H.; Fraser, Maya S.; Fullman, Nancy; Gething, Peter W.; Goldberg, Ellen M.; Graetz, Nicholas; Haagsma, Juanita A.; Hay, Simon I.; Huynh, Chantal; Johnson, Catherine O.; Kassebaum, Nicholas J.; Kinfu, Yohannes; et al. (2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.