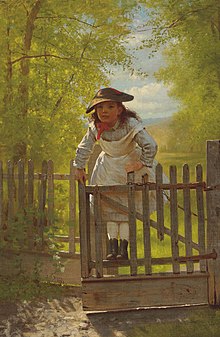

Tomboy

A tomboy is a girl who exhibits characteristics or behaviors considered typical of a boy,[1][2] including wearing masculine clothing and engaging in games and activities that are physical in nature and are considered in many cultures to be unfeminine or the domain of boys.[2] Tomboy, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), "has been connected with connotations of rudeness and impropriety" throughout its use.[3]

History and society

The OED dates the first use of the term tomboy to 1592,[3] but an earlier use is recorded in Ralph Roister Doister, which is believed to date from 1553, and was published in 1567. In nineteenth-century American culture, the usage of the word "tomboy" came to refer to a specific code of conduct that permitted young girls to exercise, wear "sensible clothing", and to eat a "wholesome diet". Because of the emphasis on a healthier lifestyle, tomboyism quickly grew in popularity during this time period as an alternative to the dominant feminine code of conduct that had limited women's physical movement.[4] In her 1898 book Women and Economics, feminist writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman lauds the health benefits of being a tomboy as well as the freedom for gender exploration: "not feminine till it is time to be".[5] Joseph Lee, a playground advocate, believed the tomboy phase crucial to physical development between the ages of eight and thirteen in 1915.[6] Tomboyism remained popular through World War I and World War II in society, literature, and then film.

During the twentieth century, Freudian psychology and backlash against LGBT social movements resulted in societal fears about the sexualities of tomboys, and this caused some to question if tomboyism leads to lesbianism.[4] Gender scholar Judith Halberstam states that while the defying of gender roles is often tolerated in young girls, adolescent girls who display masculine traits are often repressed or punished.[7] However, the ubiquity of traditionally female clothing, such as skirts and dresses has declined among the Western world where it is generally no longer considered a male trait if girls and women do not wear such clothing. An increase in the popularity of women's sporting events (see Title IX) and other activities that were traditionally male-dominated has broadened tolerance and lessened the impact of tomboy as a pejorative term.[2] Instead, as sociologist Barrie Thorne suggested, some "adult women tell with a hint of pride as if to suggest: I was (and am) independent and active; I held (and hold) my own with boys and men and have earned their respect and friendship; I resisted (and continue to resist) gender stereotypes".[8]

Throughout history, there has been a perceived correlation between tomboyishness and lesbianism.[3][9] For instance, Hollywood films would stereotype the adult tomboy as a "predatory butch dyke".[9] Lynne Yamaguchi and Karen Barber, editors of Tomboys! Tales of Dyke Derring-Do, argue that "tomboyhood is much more than a phase for many lesbians", it "seems to remain a part of the foundation of who we are as adults".[3][10] Many contributors to Tomboys! linked their self-identification as tomboys and lesbians to both labels positioning them outside "cultural and gender boundaries".[3] However, while some tomboys later reveal a lesbian identity in their adolescent or adult years, behavior typical of boys but displayed by girls is not a true indicator of one's sexual orientation.[11]

Studies

There have been few studies of the causality of women's behavior and interests, when they do not match the female gender role. One report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children suggests that preschool girls engaging in masculine-typical gender-role behavior, such as playing with toys typically preferred by boys, is influenced by genetic and prenatal factors.[12] Tomboys have also been noted to demonstrate a stronger interest in science and technology.[2]

Fiction

See also

References

- ^ Tomboy in the Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ a b c d Who Are Tomboys and Why Should We Study Them?, SpringerLink, Archives of Sexual Behavior, Volume 31, Number 4

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Jayne Relaford (1999). "Tomboy". In B. Zimmerman (ed.). Encyclopedia of Lesbian Histories and Cultures. Routledge. pp. 771–772. ISBN 0815319207. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

The word [tomboy] also has a history of sexual, even lesbian, connotations. [ ... ] The connection between tomboyism and lesbianism continued, in a more positive way, as a frequent theme in twentieth-century lesbian literature and nonfiction coming out stories.

- ^ a b Abate, Michelle Ann (2008). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-722-0.

- ^ Gilman, Charlotte Perkins (1898). Women and Economics. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company. p. 56.

- ^ Lee, Joseph (1915). Play in Education. pp. 392–393.

- ^ Halberstam, Judith: Female Masculinity, Durham: Duke University Press, 1998.

- ^ Thorne, Barrie (1993). Gender play: boys and girls in school. Rutgers University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-8135-1923-3.

- ^ a b Halberstam, Judith (1998). Female Masculinity. Duke University Press. pp. 193–196. ISBN 0822322439.

Hollywood film offers us a vision of the adult tomboy as the predatory butch dyke: in this particular category, we find some of the best and worst of Hollywood stereotyping.

- ^ Yamaguchi, Lynne and Karen Barber, ed. (1995). Tomboys! Tales of Dyke Derring-Do. Los Angeles: Alysson.

- ^ Gabriel Phillips; Ray Over (1995). "Differences between heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women in recalled childhood experiences". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 24 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1007/BF01541985.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Hines, Melissa; Golombok, Susan; Rust, John; Johnston, Katie J.; Golding, Jean; Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team (1 November 2002). "Testosterone during Pregnancy and Gender Role Behavior of Preschool Children: A Longitudinal, Population Study". Child Development. 73 (6): 1678–1687. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00498. JSTOR 3696409.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)