Treadwheel crane

A treadwheel crane (Latin: magna rota) is a wooden, human powered hoisting and lowering device. It was primarily used during the Roman period and the Middle Ages in the building of castles and cathedrals. The often heavy charge is lifted as the individual inside the treadwheel crane walks. The rope attached to a pulley is turned onto a spindle by the rotation of the wheel thus allowing the device to hoist or lower the affixed pallet.

History

[edit]Ancient Rome

[edit]

The Roman Polyspaston crane, from Ancient Greek πολύσπαστον (polúspaston, “compound pulley”), when worked by four men at both sides of the winch, could lift 3000 kg. In case the winch was replaced by a treadwheel, the maximum load even doubled to 6000 kg at only half the crew, since the treadwheel possesses a much bigger mechanical advantage due to its larger diameter. This meant that, in comparison to the construction of the ancient Egyptian pyramids, where about 50 men were needed to move a 2.5 ton stone block up the ramp (50 kg per person), the lifting capability of the Roman Polyspaston proved to be 60 times more efficient (3000 kg per person).[1] There are two surviving reliefs of Roman treadwheel cranes, the Haterii tombstone from the late first century AD being particularly detailed. De architectura contains a description of Polyspaston crane.

For larger weights of up to 100 t, Roman engineers set up a wooden lifting tower, a rectangular trestle which was so constructed that the column could be lifted upright in the middle of the structure by the means of human and animal-powered capstans placed on the ground around the tower.[2]

Middle Ages

[edit]

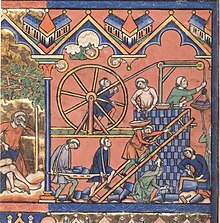

During the High Middle Ages, the treadwheel crane was reintroduced on a large scale after the technology had fallen into disuse in western Europe with the demise of the Western Roman Empire.[3] The earliest reference to a treadwheel (magna rota) reappears in archival literature in France about 1225,[4] followed by an illuminated depiction in a manuscript of probably also French origin dating to 1240.[5] In navigation, the earliest uses of harbor cranes are documented for Utrecht in 1244, Antwerp in 1263, Bruges in 1288 and Hamburg in 1291,[6] while in England the treadwheel is not recorded before 1331.[7]

Generally, vertical transport could be done more safely and inexpensively by cranes than by customary methods. Typical areas of application were harbours, mines, and, in particular, building sites where the treadwheel crane played a pivotal role in the construction of the lofty Gothic cathedrals. Nevertheless, both archival and pictorial sources of the time suggest that newly introduced machines like treadwheels or wheelbarrows did not completely replace more labor-intensive methods like ladders, hods and handbarrows. Rather, old and new machinery continued to coexist on medieval construction sites[8] and harbours.[6]

Apart from treadwheels, medieval depictions also show cranes to be powered manually by windlasses with radiating spokes, cranks and by the 15th century also by windlasses shaped like a ship's wheel. To smooth out irregularities of impulse and get over 'dead-spots' in the lifting process flywheels are known to be in use as early as 1123.[9]

The exact process by which the treadwheel crane was reintroduced is not recorded,[4] although its return to construction sites has undoubtedly to be viewed in close connection with the simultaneous rise of Gothic architecture. The reappearance of the treadwheel crane may have resulted from a technological development of the windlass from which the treadwheel structurally and mechanically evolved. Alternatively, the medieval treadwheel may represent a deliberate reinvention of its Roman counterpart drawn from Vitruvius' De architectura which was available in many monastic libraries. Its reintroduction may have been inspired, as well, by the observation of the labor-saving qualities of the waterwheel with which early treadwheels shared many structural similarities.[7]

Structure and placement

[edit]

The medieval treadwheel was a large wooden wheel turning around a central shaft with a treadway wide enough for two workers walking side by side. While the earlier 'compass-arm' wheel had spokes directly driven into the central shaft, the more advanced 'clasp-arm' type featured arms arranged as chords to the wheel rim,[10] giving the possibility of using a thinner shaft and providing thus a greater mechanical advantage.[11]

Contrary to a popularly held belief, cranes on medieval building sites were neither placed on the extremely lightweight scaffolding used at the time nor on the thin walls of the Gothic churches which were incapable of supporting the weight of both hoisting machine and load. Rather, cranes were placed in the initial stages of construction on the ground, often within the building. When a new floor was completed, and massive tie beams of the roof connected the walls, the crane was dismantled and reassembled on the roof beams from where it was moved from bay to bay during construction of the vaults.[12] Thus, the crane ‘grew’ and ‘wandered’ with the building with the result that today all extant construction cranes in England are found in church towers above the vaulting and below the roof, where they remained after building construction for bringing material for repairs aloft.[13]

Less frequently, medieval illuminations also show cranes mounted on the outside of walls with the stand of the machine secured to putlogs.[14]

Mechanics and operation

[edit]

In contrast to modern cranes, medieval cranes and hoists - much like their counterparts in Greece and Rome[15] - were primarily capable of a vertical lift, and not used to move loads for a considerable distance horizontally as well.[12] Accordingly, lifting work was organized at the workplace in a different way than today. In building construction, for example, it is assumed that the crane lifted the stone blocks either from the bottom directly into place,[12] or from a place opposite the centre of the wall from where it could deliver the blocks for two teams working at each end of the wall.[15] Additionally, the crane master who usually gave orders at the treadwheel workers from outside the crane was able to manipulate the movement laterally by a small rope attached to the load.[16] Slewing cranes which allowed a rotation of the load and were thus particularly suited for dockside work appeared as early as 1340.[17] While ashlar blocks were directly lifted by sling, lewis or devil's clamp (German Teufelskralle), other objects were placed before in containers like pallets, baskets, wooden boxes or barrels.[18]

It is noteworthy that medieval cranes rarely featured ratchets or brakes to forestall the load from running backward.[19] This curious absence is explained by the high friction force exercised by medieval treadwheels which normally prevented the wheel from accelerating beyond control.[16]

Harbour usage

[edit]

According to the "present state of knowledge" unknown in antiquity, stationary harbour cranes are considered a new development of the Middle Ages.[6] The typical harbour crane was a pivoting structure equipped with double treadwheels. These cranes were placed docksides for the loading and unloading of cargo where they replaced or complemented older lifting methods like see-saws, winches and yards.[6]

Two different types of harbour cranes can be identified with a varying geographical distribution: While gantry cranes which pivoted on a central vertical axle were commonly found at the Flemish and Dutch coastside, German sea and inland harbours typically featured tower cranes where the windlass and treadwheels were situated in a solid tower with only jib arm and roof rotating.[20] Dockside cranes were not adopted in the Mediterranean region and the highly developed Italian ports where authorities continued to rely on the more labor-intensive method of unloading goods by ramps beyond the Middle Ages.[21]

Unlike construction cranes where the work speed was determined by the relatively slow progress of the masons, harbour cranes usually featured double treadwheels to speed up loading. The two treadwheels whose diameter is estimated to be 4 m or larger were attached to each side of the axle and rotated together.[6] Their capacity was 2–3 tons which apparently corresponded to the customary size of marine cargo.[6] Today, according to one survey, fifteen treadwheel harbour cranes from pre-industrial times are still extant throughout Europe.[22] Some harbour cranes were specialised at mounting masts to newly built sailing ships, such as in Danzig, Cologne and Bremen.[20] Beside these stationary cranes, floating cranes which could be flexibly deployed in the whole port basin came into use by the 14th century.[20]

Surviving examples

[edit]Original

[edit]A treadwheel crane survives at Chesterfield, Derbyshire and is housed in the Museum. It has been dated to the early 14th century and was housed in the top of the church tower until its removal in 1947. It was reconstructed in the Museum for its opening in 1994.

A treadwheel crane survives at Guildford, Surrey, United Kingdom. It dates from the late 17th or early 18th century and formerly stood in Friary Street. It was moved in 1970, having last been used ca. 1960 to move materials for Guildford Cathedral. It is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and a Grade II* listed building.[23]

A treadwheel crane survives at Harwich, Essex, United Kingdom. It was built in 1667 and formerly stood in the Naval Yard. It was moved to Harwich Green in 1932. The crane has two treadwheels of 16 feet (4.88 m) diameter by 3 feet 10 inches (1.17 m) wide on an axle 13+1⁄2 inches (340 mm) diameter. It is the only double wheel treadwheel crane in the United Kingdom.[24] The crane is a Grade II* listed building.[25]

-

Guildford treadwheel crane

-

Harwich treadwheel crane

Reconstructions

[edit]A reconstruction of a 13th-century treadwheel crane can be seen in action at the site Guédelon Castle, Treigny, France. It is used for lifting mortar, rubble, ashlar blocks, and wood. The object of Guédelon Castle is to build a fortress castle using only the techniques and materials of 13th-century medieval France.[26]

-

A treadwheel crane or 'squirrel cage' at Guédelon Castle.

Crane Gate (Polish: Brama Żuraw) (German: Krantor), Gdańsk was built before 1366. It was destroyed by the soviet troops during the fighting for the city in early 1945. The brick structure survived, the wooden parts have been restored.

-

Gdańsk Crane

A reconstruction of a double wheel treadwheel crane is in use at Prague Castle, Czech Republic.[27]

A Treadwheel Crane was used in the film Evan Almighty, when Evan complained to God that he needed a crane to construct the Ark in suburban Washington, D.C.

References

[edit]- ^ Dienel & Meighörner 1997, p. 13

- ^ Lancaster 1999, pp. 426−432

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 514

- ^ a b Matthies 1992, p. 515

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 526

- ^ a b c d e f Matheus 1996, p. 345

- ^ a b Matthies 1992, p. 524

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 545

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 518

- ^ Matthies 1992, pp. 525f.

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 536

- ^ a b c Matthies 1992, p. 533

- ^ Matthies 1992, pp. 532ff.

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 535

- ^ a b Coulton 1974, p. 6

- ^ a b Dienel & Meighörner 1997, p. 17

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 534

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 531

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 540

- ^ a b c Matheus 1996, p. 346

- ^ Matheus 1996, p. 347

- ^ These are Bergen, Stockholm, Karlskrona (Sweden), Kopenhagen (Denmark), Harwich (England), Gdańsk (Poland), Lüneburg, Stade, Otterndorf, Marktbreit, Würzburg, Östrich, Bingen, Andernach and Trier (Germany). Cf. Matheus 1996, p. 346

- ^ Historic England. "THE TREADWHEEL CRANE, MILLBROOK (west side), GUILDFORD, GUILDFORD, SURREY (1377866)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ "Treadwheel Crane". The Harwich Society. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "OLD NAVAL YARD CRANE, HARWICH GREEN, HARWICH, TENDRING, ESSEX (1187899)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ Tom Scott (26 September 2022). "I thought the treadmill crane was fictional" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Man-powered medieval crane at Prague Castle". Radio Praha. 5 September 2006. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

Sources

[edit]- Dienel, Hans-Liudger; Meighörner, Wolfgang (1997), "Der Tretradkran", Publication of the Deutsches Museum (Technikgeschichte Series) (2nd ed.), München

- Coulton, J. J. (1974), "Lifting in Early Greek Architecture", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 94: 1–19, doi:10.2307/630416, JSTOR 630416

- Lancaster, Lynne (1999), "Building Trajan's Column", American Journal of Archaeology, 103 (3): 419–439, doi:10.2307/506969, JSTOR 506969

- Matheus, Michael (1996), "Mittelalterliche Hafenkräne", in Lindgren, Uta (ed.), Europäische Technik im Mittelalter. 800 bis 1400. Tradition und Innovation (4th ed.), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 345–348, ISBN 3-7861-1748-9

- Matthies, Andrea (1992), "Medieval Treadwheels. Artists' Views of Building Construction", Technology and Culture, 33 (3): 510–547, doi:10.2307/3106635, JSTOR 3106635

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Treadwheel cranes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Treadwheel cranes at Wikimedia Commons