Ullucus

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

| Olluco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Basellaceae |

| Genus: | Ullucus Caldas |

| Species: | U. tuberosus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ullucus tuberosus Caldas

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 74.4 kcal (311 kJ) |

15.3 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 0.9 g |

0.1 g | |

2.6 g | |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[2] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[3] Source: Cultivariable[1] | |

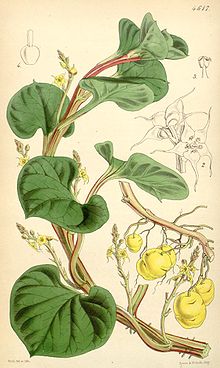

Ullucus is a genus of flowering plants in the family Basellaceae, with one species, Ullucus tuberosus, a plant grown primarily as a root vegetable, secondarily as a leaf vegetable.

Olluco is one of the most widely grown and economically important root crops in the Andean region of South America, second only to the potato.[4] The tuber is the primary edible part, but the leaf is also used and is similar to spinach.[5] They are known to contain high levels of protein, calcium, and carotene. Olluco was used by the Incas prior to arrival of Europeans in South America.[6]

Ullucus tuberosus has a subspecies, Ullucus tuberosus subsp. aborigineus, which is considered a wild type. While the domesticated varieties are generally erect and have a diploid genome, the subspecies is generally a trailing vine and has a triploid genome.[5]

Vernacular names

Spanish: olluco, papalisa, ulluco, melloco.[5]

Usage

The major appeal of ulluco is its crisp texture which, like the jicama, remains even when cooked. Because of its high water content, ulluco is not suitable for frying or baking, but it can be cooked in many other ways like the potato. In the pickled form, it is added to hot sauces. It is the main ingredient in the classic Peruvian dish olluquito con ch'arki and a basic ingredient together with the mashua in the typical Colombian dish cocido boyacense. They are generally cut into thin strips.

Oblong and thin, they grow to a few inches long. Varying in color, papalisa tubers may be orange/yellow in color with red/pink/purple freckles. In Bolivia, they grow to be very colorful and decorative, though with their sweet and unique flavor they are rarely used for decoration. When boiled or broiled they remain moist; the texture and flavor are very similar to the meat of the boiled peanut without the skin. Unlike the peanut meat becoming soft and mushy, ulluco remain firm and almost crunchy.

They are a traditional food in Catholic Holy Week celebrations in Bolivia.

See also

References

- ^ "Nutrition facts for oca, ulloco, and mashua". Cultivariable. 2013-06-11. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ http://www.bioversityinternational.org/uploads/tx_news/Andean_roots_and_tubers_472.pdf#page=8&zoom=auto,-262,4

- ^ a b c d National Research Council (U S.) (1989). Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. National Academy Press. pp. 105–113.

- ^ Hernández Bermejo, J. E.; León, J. (eds.) (1994). Neglected crops: 1492 from a different perspective. Roma: FAO. ISBN 92-5-103217-3

- ^ Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)