User:Amitchell125/tribalhidage

The Tribal Hidage is a list of thirty-four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and small territories ('tribes'), each of which was assessed in terms of the number of hides that the tribe represented. The list is headed by Mercia and is almost exclusively of peoples who lived south of the river Humber. The Tribal Hidage is of great importance to historians, in part because it mentions peoples that are not recorded elsewhere.

Three different versions (or recensions) of the Tribal Hidage have survived, two of which resemble each other: Recension A dates from the 11th century and is part of a miscellany of works; Recension B is contained in a 17th century Latin treatise; a third recension (C) contains many omissions and spelling variations.A date for the production of the original (now lost) manuscript that was used to produce the Tribal Hidage in its surviving forms has eluded scholars.

The purpose of the Tribal Hidage remains unknown: one theory is that it may have been a tribute list created by a king, but it has been argued that other interpretations cannot be ignored. The hidage figures may be purely symbolic. They may represent an early example of book-keeping. It is generally thought that the Tribal Hidage originated from Mercia, which held extensive hegemony over the Southumbrians until the start of the 9th century, but some historians have proposed that the text is of Northumbrian origin.

The hide assessments

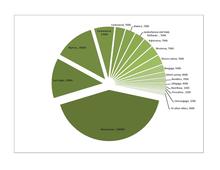

[edit]The Tribal Hidage is, according to D. P. Kirby's description, "a list of total assessments in terms of hides for a number of territories south of the Humber, which has been variously dated from the mid-7th to the second half of the 8th century".[1] A hide was an Anglo-Saxon unit of land measurement, the actual value of which is unknown, [2] but which is thought to have equalled approximately 120 acres (0.49 km2; 0.19 sq mi). It was considered to be the amount needed to sustain a freeman and his family. A man from every five hides was expected to serve in the king's 'fyrd'.[3] Most of the kingdoms of the Heptarchy are included in the list. The following lists gives the names of each of the 'tribes' as recorded in the earliest and most complete version of the Tribal Hidage:

- Myrcna landes... ...þær mon ærest Mrycna hæt.Mercia (The area first called Mercia)[4] — 30,000 hides

- Wocensaetna (name taken from The Wrekin, in Shropshire[5]) — 7,000 hides

- Westerna Magonsæte[4] — 7,000 hides

- Pecsætna ('dwellers in the Peak[5]) — 1,200 hides

- Elmed sætna Elmet[4] — 600 hides

- Lindesfarona mid Hæþ feldlande Lindsey (with Hatfield Chase, South Yorkshire[5]) — 7,000 hides

- Suþ gyrwa (The Gyrwe, in the vicinity of Peterborough[5]) — 600 hides

- Norþ gyrwa — 600 hides

- East wixna (possibly located around Wisbech[4]) — 300 hides

- West wixna — 600 hides

- Spalda (Spalding, Lincolnshire[4] or Spaldwick, Cambridgeshire[6]) — 600 hides

- Wigesta (possibly Wigginhall, Norfolk[4]) — 900 hides

- Herefinna (unidentified) — 1,200 hides

- Sweord ora (Sword Point, near Whittlesey Mere, Cambridgeshire[4]) — 300 hides

- Gifla (River Ivel, Buckinghamshire[4]) — 300 hides

- Hicca (Hitchin, Hertfordshire[4]) — 300 hides

- Wiht gara (Isle of Wight[4]) — 600 hides

- Noxgaga (unidentified[7]) — 5,000 hides

- Ohtgaga (unidentified[7]) — 2,000 hides

At this point in the list, the total number of hides is given, "þæt is six ond syxtig þusend hyda ond an hund hyda..." — 'that is 66,100 hides'.

- Hwinca[4] — 7000 hides

- Ciltern sætna The Chiltern dwellers[4] (Chiltern Hills) — 4,000 hides

- Hendrica (unidentified[7]) — 3,500 hides

- Unecungaga (unidentified[7]) — 1200 hides

- Arosætna (River Arrow, Warwickshire[4]) — 600 hides

- Færpinga (Charlbury, Oxfordshire[4]) — 300 hides

- Bilmiga (possibly located in Rutland or Northamptonshire[4]) — 600 hides

- Widerigga (Wittering, Cambridgeshire or Werrington, Peterborough[4]) — 600 hides

- Eastwilla (possibly 'Willeybrook', Northamptonshire[4]) — 600 hides

- Westwilla ('stream of the Fen area'[4]) — 600 hides

- East engle The East Angles — 30,000 hides

- East sexena The East Saxons — 7,000 hides

- Cantwarena The 'Men of Kent' — 15,000 hides

- Suþsexena The South Saxons — 7,000 hides

- Westsexena The West Saxons — 100,000 hides

At this point in the list, the total number of hides is given, incorrectly, "Ðis ealles twa hund þusend ond twa ond feowertig þusend hyda ond syuan hund hyda..." — 'that is 242,700 hides'.

It is not clear why these larger regions were juxtaposed alongside numerous smaller ones. A number of names, such as the Hicce, have only been located by means of place-names evidence: others cannot be located at all.[6]

Barbara Yorke suggests that the -sætan/sæte form of several of the place-names are an indication that they were named after a feature of the local landscape and that they were dependent administrative units and not independent kingdoms, some of which may have been created as such after the main kingdoms were stabilized.[8] The minor peoples in the region around Middle Anglia seem to constitute a "lower level of social organisation", according to Blair.[9]

The hidage assessments were not produced as a result of an accurate survey, as the all the figures are rounded off. The methods of assessment used probably differed according to the size of the region that was being assessed,[10] with the figures for the largest kingdoms being added to what was originally a genuine survey.[9] The figures given may be of purely symbolic significance, reflecting the status of each tribe at the time it was assessed.[11] The totals given within the text for the figures suggest that the Tribal Hidage was perhaps used as a form of book-keeping.[12]

The surviving manuscripts

[edit]

A manuscript, now lost,[13] was originally used to produce the three known different recensions of the Tribal Hidage: these have been named Recensions A, B and C.[14]

Recension A, the earliest and most complete copy of the Tribal Hidage, which dates from the 11th century, is included along with a miscellany of other works, written in Old English and Latin, that includes Aelfric's Latin Grammar and his homily De initio creaturæ, a work written in 1034.[15] It is in the keeping of the British Library, reference MS Harley 3271.[note 1] It was completed by several different scribes,[16] at a date no later than 1032.[17] Recension B, which resembles Recession A, is contained in a 17th century Latin treatise, Archaeologus in Modum Glossarii ad rem antiquam posteriorem, that was written by Henry Spelman in 1626.[17] The grammar used shows the Latin context of the text, but the tribal names are given in Old English. There are significant differences in spelling between the two recessions.[18]

Recension C consists of six Latin documents, each being grouped with the Burghal Hidage. The texts each contain common ommissions and spellings. Four versions, of 13th century origin, formed part of a collection of legal texts and "may have been intended to act as part of a record of native English custom". The other two versions are a century older: one is flawed and may have been a scribe's exercise and the other was part of a set of legal texts.[19]

Importance

[edit]The Tribal Hidage is a valuable record for historians. It is unique in that no similar text has survived. It lists several minor kingdoms and tribes that are not recorded anywhere else[13] and is generally agreed to be the earliest fiscal document that has survived from mediaeval England.[20]

It has been used by scholars as evidence of the structure and formation of the Mercian kingdom[9] and to build elaborate models of political hegemony,[21] for instance in providing evidence that the larger Anglo-Saxon kingdoms contested the small bordering territories concentrated in the Middle Anglia region.[22]

Purpose

[edit]The purpose of the Tribal Hidage remains unknown:[9] it has long been debated by scholars.[14] Over the years a large number of theories have been suggested for its purpose and a range of dates for the creation of the original manuscript have been proposed.[6]

According to many experts, the Tribal Hidage was a tribute list created upon the instructions of an Anglo-Saxon king such as Offa of Mercia, Wulfhere of Mercia or Edwin of Northumbria — but it may have been used for different purposes at various times during its history.[13] Higham notes that the syntax of the text requires that a word implying 'tribute' was omitted from each line and so it was "almost certainly a tribute list".[23] The large size of the West Saxon hidation indicates that there were close links between the scale of tribute and any political considerations.[24]

Yorke disputes that the interpretation of an overlord using the Tribal Hidage to exact tribute is the only one that is feasible, arguing that the "unusual circumstances" of the Wiht gara and the Suþ gyrwa may have made them the only minor tribes in the list to be ruled by their own tribute-paying kings.[6]

Origin

[edit]

Some of the Tribal Hidage, which may originate from several different sources,[9] comes from a period when the minor principalities had social and political importance.[21]

Featherstone concludes that the original material (dating from late 7th century Mercia) was then used to be included in a late 9th century document. Alternatively, Brooks has proposed that the text is of Northumbrian origin.[25]

It is generally thought that the Tribal Hidage originated from Mercia:[12] Featherstone asserts that the Mercian kingdom "was at the centre of the world mapped out by the Tribal Hidage".[14] The near universal agreement for the text being of Mercian origin is in part because the kings of Mercia are known to have held extensive power over other Anglo-Saxon kings from the late 7th to the early 9th centuries, but also because the list, headed by Mercia, is almost exclusively of peoples who lived south of the river Humber.[26]

Higham has argued that because the date of the original information is unknown and the largest Northumbrian kingdoms are not included in the Tribal Hidage, it cannot be proved to be a tribute list of Mercian origin. He notes that Elmet, which was never a province of Mercia, is included in the list[27] and suggests that the Tribal Hidage may have been a tribute list drawn up by Edwin of Northumbria in the 620s[28] and that it probably originated before 685: after which no Northumbrian king exercised imperium over the Southumbrian kingdoms.[29] According to Higham, the values assigned to each people are likely to be specific to the events of 625-626, representing the individual contracts made between Edwin and those who recognised his overlordship at that time. This explains the artifical and rounded nature of the figures that were arrived at: the figure of 100,000 hides for the West Saxons was probably the largest number Edwin knew.[30] The Northumbrian origin theory has not been generally accepted as convincing.[31]

It is possible that Paulinus may have been responsible for drawing up the original list: the variations in spelling within the later copy may have been because he was unused to writing the names of unfamiliar peoples in Old English.[32]

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Kirby, Kings, p. 9.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, p. 94.

- ^ Neal, Defining power in the Mercian Supremacy, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Kirby, Kings, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Yorke, in Frazer and Tyrell, Social Identity, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d Kirby, Kings, p. 10.

- ^ Yorke, in Frazer and Tyrell, Social Identity, pp. 84, 86.

- ^ a b c d e Blair, Tribal Hidage, p. 456.

- ^ Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 25.

- ^ Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 28.

- ^ a b Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 27.

- ^ British Library, Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts

- ^ Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, pp. 24-25.

- ^ a b Neal, Defining power in the Mercian Supremacy, p. 19.

- ^ Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 25.

- ^ Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 26.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, p. 74.

- ^ a b Blair, Tribal Hidage, p. 455.

- ^ Woolf, Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain, pp. 99-100.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, p. 75.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, p. 94.

- ^ Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 30.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, pp. 74-75.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, pp. 75, 76.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, p. 50.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, p. 76.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, pp. 94-95.

- ^ Kirby, Kings, p. 191, note 45.

- ^ Higham, An English Empire, pp. 96-97.

Further reading

[edit]- Dumville, David (1989). "The Tribal Hidage: an introduction to its texts and their history". In Bassett, S. (ed.). Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Leicester: Leicester University Press. pp. 225–30. ISBN 0718513177.

External links

[edit]- Recension A: The British Library's detailed record for Harley 3271 (Recension A), with a link to an image of the mediaeval manuscript.

- Recensions A, B: The Tribal Hidage The text of recensions A & B of the Tribal Hidage, transcribed and compared on the Georgetown University web site.

- Recension B: Pages 291-292 of the 1687 edition of Henry Spelman's Glossarium Archaiologicum (1626), the source of Recension B of the Tribal Hidage.

- Recension C: see Hill and Rumble in 'Sources'.

Sources

[edit]- Frazer, William O. and Tyrrell Andrew, ed. (2000). Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain. London and New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-0084-9.

- Blair, John (1999). "Tribal Hidage". The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Featherstone, Peter (2001). "The Tribal Hidage and the Ealdormen of Mercia". In Brown, Michelle P. & Farr, Carol Ann (ed.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Higham, N. J. (1995). An English Empire: Bede and the Early Anglo-Saxon Kings. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4424-3.

- Hill, David; Rumble, Alexander R. (1996). The Defence of Wessex: the Burghal Hidage and Anglo-Saxon Fortifications. Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3218-0.

- Kirby, D.P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 1-415-24211-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Neal, James R. (May 2008). "Defining power in the Mercian Supremacy: An examination of the dynamics of power in the kingdom of the borderers. (Submitted thesis)". Reno: University of Nevada. Retrieved 17 August 2011.