User:Jacqke/Banjo origins

-

1707, Jamaica or Caribbean Islands. "Strum strumps". Notebook of Hans Sloan

-

Banjo collected by John Gabriel Stedman in Surinam circa 1770-1777.

-

Image of a Creole bania from the pre-1800 book Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Suriname by Captain John Gabriel Stedman

-

1780s, South Carolina. By John Rose.

-

Banjo or string instrument from Latrobe's journal, February 1819

-

Circa 1840. Gourd banjo neck made by William Esperance Boucher, Jr, attached by someone to old gourd banjo body. Boucher didn't sell these.

-

1845. Banjo made by William Esperance Boucher, Jr. This is the banjo which was involved with the rise of the minstrel tradition.

-

Another view of a Bourcher banjo. Circa 1845.

-

1856, William Sidney Mount, The Banjo Player

-

1865. Young black woman with banjo.

-

1860-1865 Banjo

-

1878. Thomas Eakins, American Realism painter. Taught Henry Ossawa Tanner before Tanner went to Europe.

-

Circa 1880, Charles Ethan Porter. Produced by African American artist.

-

1881. Léon Delachaux, Swiss painter, The Banjo Player

-

Untitled painting from 1882 by Thomas Hovenden showing a man playing a banjo. Appears to be "Sam", the same man in another of Hovenden's paintings.

-

1893, Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson. Produced by African American artist.

-

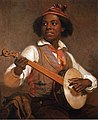

No date. Two Musicians, by Robert Lee MacCameron (1866-1912). He was in Paris when Tanner was, studying under Jean Leon Gerome[1] (like Tanner)

-

John Eastman, image discussed by Kristine R. Gaddy in Well of Souls

-

1870. Song of Mary Blane by Frank Buchser, Swiss painter.

-

Ravens or crows in imitation of African American string band, includes tanbourine, bass, banjo, drum, bones.

-

Banjo in Royal Museum for Central Africa, purchased from the Bana Lupemba Orchestra.

-

Banjo played by former slave, Henry Dobson, circa 1878.

-

1929. The Banjo Player by Hale Woodruff, African American artist.

Drumhead lutes[edit]

Although the banjo can be shown to be a creation of descendants of Africans in the Caribbean and Americas, and developed further in the United States by both African Americans and White Americans, the instrument has characteristics that place it into a worldwide family of instruments called drumhead lutes.

This grouping is not part of the Hornbostel–Sachs system of categorization, but may be a non-academic or folk categorization. Hornbostel-Sachs doesn't examine the soundboard, but details the body type and angle of the strings. Drumhead lutes focuses on the soundboard. It consists lutes with a skin soundboard stretched over a hollow body. The bodies vary and include bodies carved from wood, bodies in which wood strips have been glued into a bowl, bodies in the form of a ring or tube, and bodies made of calabash or gourd.

The banjo has a skin top, replaced in modern times with a synthetic skin, stretched over a ring of wood or metal or a combination of these. As a skin top instrument, it bears a relationship to an early form of the lute, called barbat. This is the lute which was developed into the oud. The skin-topped variant was long ago replaced by wood, creating a different sound than they would have originally had. Today, the Indonesian and Yemeni qanbus is a skin-topped descendant of the barbat.

Other skin topped lutes include the Middle-Eastern and Central-Asian kamancheh and kobyz, the Iranian and Afghanistan versions of the rubab, Iranian and Central Asian tar, Turkish Yayli tambur and cumbus, Tajikistan Pamiri rubab, European Balkans gusle, the South Asian sarangi and sarinda and sarod, Chinese plucked qinqin (also now wood topped), Vietnamese dan sen (also now wood topped), Japanese shamisen (also Okinawan sanshin and Chinese Sanxian), Mongolian igil, Nepali tungna and aarbajo, Nepali dramyin, Chinese bowed lutes such as huqin, dahu and erhu, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, a whole family of bowed instruments such as salo, saw duang and saw sam sai, Tro Khmer and Tro.

Africa has many examples of skin-topped stringed instruments, some of which are plucked lutes, some bowed lutes, and some forming a group called harp-lutes. In some cases, these are no longer skin topped. Examples include the ancient Egyptian lute, the akonting, bobre,bolombatto, cimboa, endingidi goje, imzad, kontigi, kora, kukkuma, Lokanga bara, masenqo, ngoni, orutu, ramkie, seperewa, simbing, sintir (also called guembri, garaya, lotar or loutar), xalam and zeze. In Africa, instruments developed locally. Possible influences include ancient Egyptian lutes, and contact with Muslim, Indian and Indonesian cultures.

Lutes as seen in Africa[edit]

"More than 60 plucked lute traditions have been identified in Africa"--Tabler, Winnans

Theory 1, George R. Gibson, Black Banjo, Fiddle, and Dance in Kentucky and the Amalgamation of African American and Anglo-American Folk Music[edit]

The Portuguese Empire took European culture to many places across the globe and were involved in the global slave trade. They mixed with the women of the countries they visited, creating creole peoples.

Gibson theorizes that "Luzon Creoles", people living along the banks of the Gambia River in Central Africa, mixed European and African musical instruments. They had been living on the banks of the Gambia for about 100 years, by 1620, and were there when slaves began to be imported to the Caribbean. Gibson points out this gave a group with access to European musical instruments such as the bandora to blend those musical instrument ideas with African musical instruments, prior to any slave ships departing to the Caribbean.

They have little varietie of instruments, that which is most common in use, is made of a great gourd, and a neck thereunto fastened, resembling, in some sort, our bandora; but they have no manner of fret, and the stings...with pinnes they wind and bring to agree in tuneable notes, having not above six strings on their greatest instrument. --Robert Johnson, winter of 1620-1621, on the Gambia River in West Africa

Gibson points to this group as being the common thread that much of the slave culture had in common. They came from a place in which there were drumhead or skin-topped lutes, candidates as banjo relatives, to include the akonting. They were imported to the islands of the Caribbean, which had little contact with each other, yet which had a common musical culture (calenda dance/stickfighting, drumming, banjo, gathering together in the late evening). By having having common knowledge of an instrument, slaves on the different Caribbean Islands could independently re-create the instruments; there would be no need for the knowledge to spread between the islands. Different creators in the islands would lead to variations in the newly constructed banjos/lutes.

Slaves with this culture were also imported from the Caribbean (and directly from Africa?) to the United States. An early description of their parties in common was recorded in New York about 1845.

Early race mixing was common in Virginia and Maryland, between indentured white women and blacks (some were indentured early on, some slaves). Some of these moved to Kentucky, numbering in the thousands by 1790.<Gibson pages 225-226, 247#12). Some of these families hand into a traditional of being Luzon creoles, and genetic testing has confirmed that this male black man white woman pairing in some of the families with this tradition.

Those families mixer in Kentucky with both white and black families; the banjo was endemic to to mountain region, arriving with these families and party of their culture in the years before the minstrel shows began.

Theory 2 -- Africans develop the instrument in the Caribbean and take it to America

Lutes in the Caribbean[edit]

Banjo in America before minstrel modification[edit]

-gourd banjo described -- John "Picayune" Butler

Spiritual connections[edit]

Dancers possessed with spirit. Banjos and bottle containers for spirits to live in. Spirits summoned. Spirits can possess.

Santería--spirits can inhabit shells

Orisha, an African-rooted religion practised in Trinidad and Tobago,

Calenda

Clergy on Calenda, pages 92-96

Dancing the calenda had spiritual connotations as singers would "praise their orisha, vodoun and inkici" and say they were praising the Saints of Heaven. (p 96). Form of protest--danced in spite of or maybe because of white Christian objections.(Well of Souls) Sexually freedom expressed in dance (the opposite of the Christian "modesty" demanded by masters, their religion and their authority.(Well of Souls and around p96) Also a form of martial art, stick fighting, which made them cocky (not an attitude the masters liked)(Well of Souls). Brought them together with a sense of community, when the masters were trying to destroy any community, destroy connections that would let them bond together against the masters).(Well of Souls).

Spirit containers[edit]

Line to circle, symbolizing reality[edit]

Destruction and confiscation of containers by priests[edit]

-collection in European collections

Culture of Dancing[edit]

-similarities to John Rose painting -elements of the dance culture seen in John Rose painting, broken down -calinda

Range of culture[edit]

-NY to the Caribbean, S Carolina, New Orleans

United States[edit]

Friendly Black-White banjo interaction[edit]

-Old Time Mountain Banjo -Kentucky?

Cultural appropriation[edit]

According to George R. Gibson, there was an effort in the 19th century to "divorce the banjo from its African American origins" (BR&B, ch 14, p.246, footnote 4). That separation came in a number of ways, including the rise of the minstrel movement, the introduction of Jim Crow and its push into the mid-20th century, the rise of the elevation movement in the 1880s through the early 1900s, the economic pressure to limit black profits in show business, record sales, performance venues, the association of the banjo with backwardness (first through minstrel shows, then through country corn in the face of the electric guitar, liberality and rock-n-roll).

The jazz banjo of the 1920s went out in the 1930s (the instrument of a taxi-driver, even for white banjoists) in the face of 40s/50s pop culture.

Minstrel movement--there has been a persistent claim that Joel Walker Sweeney was the first white man to play the banjo. Gibson believes this myth was deliberate, an attempt to culturally appropriate or steal the banjo from African Americans <BR&B, ch 14, p.246, footnote 4> This would also, in effect, also rob earlier white banjoists of credit for their banjo musicianship.

-Minstrelsy

-Elevation

--Techology changes banjo

---Metal

---Shiny

---Reenforced neck for metal strings

---Tinny sound or bell-like sound

-

William Sidney Mount - The Banjo Player, circa 1850

-

1934. Part of a series of Uncle Nat'chel advertisments, painted by Henry Hintermeister. This was titled "Jes' Act Nat'chel, Sonny".

Countermovement against cultural appropriation[edit]

-Trio of images, realism and impressionism artists

-modern musicians taking up the banjo

--Rhianna Giddens

--Taj Mahal

Civil War[edit]

-

Union soldier with a minstrel-style banjo. This one in style of Boucher.

-

African American sailor with a banjo during the American Civil War, on board the USS Hunchback. African American with minstrel-style banjo.

-

Labeled "minstrels", on the Flagship Wabash, American Civil War, this group has two banjos and a guitar as part of their music.

-

1864, USS Mendota. There was more equality on sailing ships and in the Navy than in US society (though African Americans and freed slaves were held to lower ranks).

Effect[edit]

The banjo went into serious decline among African Americans until it has become a novelty to see Rhianna Giddens or Dom Flemons playing string band music. Even Taj Mahal didn't use the banjo as his main instrument.

Women and the banjo[edit]

-

1920

-

2014

-

Taylor Swift with banjo, 2012

Worldwide use[edit]

-

Dom Flemons with a gourd banjo at the Sweeney Banjofest

-

Stian Carstensen at Buckleys Oslo Jazz festival, Norway

Sources[edit]

- Robert B. Winans, ed. (2018). Banjo Roots and Branches. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- Kristina R. Gaddy (4 October 2022). Well of Souls. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393866803.

- "Views of the Creole Bania". 28 February 2019.

- "uncovering-the-hidden-history".

- Karen Elizabeth Linn (Winter 1990). "The "Elevation" of the Banjo in Late Nineteenth-Century America". American Music. 8 (4). University of Illinois Press.

- Making Music: The Banjo, Baltimore, and Beyond Posted by Dave Tabler, Essay by Robert Winans

References[edit]

- ^ "Facts about Robert Lee MacCameron".

- ^ a b Dr. Leo G. Mazow; Dr. Beth Harris. Hale Woodruff, The Banjo Player. Smart History, the Center for Public Art History.

- ^ Richard Stemp. "Day 81 — The Banjo Lesson". drrichardstemp.com.

- ^ "The Banjo Player (Primary Title)". Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

- ^ a b DR. LEO G. MAZOW; DR. BETH HARRIS. "Hale Woodruff, The Banjo Player". Smart History, the Center for Public Art History.

![No date. Two Musicians, by Robert Lee MacCameron (1866-1912). He was in Paris when Tanner was, studying under Jean Leon Gerome[1] (like Tanner)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Two_musicians%2C_by_Robert_Lee_MacCameron_%281866-1912%29.jpg/97px-Two_musicians%2C_by_Robert_Lee_MacCameron_%281866-1912%29.jpg)