User:Mr. Ibrahem/Vitamin B12 deficiency

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypocobalaminemia, cobalamin deficiency |

| |

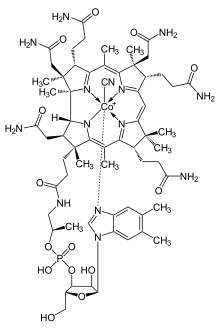

| Cyanocobalamin | |

| Specialty | Neurology, hematology |

| Symptoms | Decreased ability to think, depression, irritability, abnormal sensations, changes in reflexes[1] |

| Complications | Megaloblastic anemia[2] |

| Causes | Poor absorption, decreased intake, increased requirements[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood levels below 120–180 pmol/L (170–250 pg/mL) in adults[2] |

| Prevention | Supplementation in those at high risk[2] |

| Treatment | Supplementation by mouth or injection[3] |

| Frequency | 6% (<60 years old), 20% (>60 years old)[1] |

Vitamin B12 deficiency, also known as cobalamin deficiency, is the medical condition of low blood and tissue levels of vitamin B12.[4] In mild deficiency, a person may feel tired and have a reduced number of red blood cells (anemia).[1] In moderate deficiency, soreness of the tongue may occur, and the beginning of neurological symptoms, including abnormal sensations such as pins and needles.[1] Severe deficiency may include symptoms of reduced heart function as well as more severe neurological symptoms, including changes in reflexes, poor muscle function, memory problems, decreased taste, decrease level of consciousness, and psychosis.[1] Infertility may occur.[1][5] In young children, symptoms include poor growth, poor development, and difficulties with movement.[2] Without early treatment, some of the changes may be permanent.[6]

Causes are categorized as decreased absorption of vitamin B12 from the stomach or intestines, deficient intake, or increased requirements.[1] Decreased absorption may be due to pernicious anemia, surgical removal of the stomach, chronic inflammation of the pancreas, intestinal parasites, certain medications, and some genetic disorders.[1] Medications that may decrease absorption include proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor blockers, and metformin.[7] Decreased intake may occur in vegetarians and the malnourished.[1][8] Increased requirements occur in people with HIV/AIDS, and in those with shortened red blood cell lifespan.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on blood levels of vitamin B12 below 120–180 pmol/L (170 to 250 pg/mL) in adults.[2] Elevated methylmalonic acid levels may also indicate a deficiency.[2] A type of anemia known as megaloblastic anemia is often but not always present.[2]

Treatment consists of using vitamin B12 by mouth or by injection; initially in high daily doses, followed by less frequent lower doses as the condition improves.[3] If a reversible cause is found, that cause should be corrected if possible.[9] If no reversible cause is found—or when found it cannot be eliminated—lifelong vitamin B12 administration is usually recommended.[10] Vitamin B12 deficiency is preventable with supplements containing the vitamin: this is recommended in pregnant vegetarians and vegans, and not harmful in others.[2] Risk of toxicity due to vitamin B12 is low.[2]

Vitamin B12 deficiency in the US and the UK is estimated to occur in about 6 percent of those under the age of 60, and 20 percent of those over the age of 60.[1] In Latin America, about 40 percent are estimated to be affected, and this may be as high as 80 percent in parts of Africa and Asia.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hunt, A; Harrington, D; Robinson, S (4 September 2014). "Vitamin B12 deficiency" (PDF). BMJ. 349. g5226. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226. PMID 25189324. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Vitamin B12 — Health Professional Fact Sheet". National Institutes of Health: Office of Dietary Supplements. 2016-02-11. Archived from the original on 2016-07-27. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ a b Wang, H; Li, L; Qin, LL; Song, Y; Vidal-Alaball, V; Liu, TH (March 2018). "Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3. CD004655. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004655.pub3. PMC 5112015. PMID 29543316.

- ^ Herrmann, Wolfgang (2011). Vitamins in the prevention of human diseases. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 245. ISBN 9783110214482. Archived from the original on 2021-08-05. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ "Complications". nhs.uk. 2017-10-20. Archived from the original on 2021-07-16. Retrieved 2018-05-09.

- ^ Lachner, C; Steinle, NI; Regenold, WT (2012). "The neuropsychiatry of vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly patients". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 24 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11020052. PMID 22450609.

- ^ Miller, JW (1 July 2018). "Proton Pump Inhibitors, H2-Receptor Antagonists, Metformin, and Vitamin B-12 Deficiency: Clinical Implications". Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.). 9 (4): 511S–518S. doi:10.1093/advances/nmy023. PMC 6054240. PMID 30032223.

- ^ Pawlak, R; Parrott, SJ; Raj, S; Cullum-Dugan, D; Lucus, D (February 2013). "How prevalent is vitamin B(12) deficiency among vegetarians?". Nutrition Reviews. 71 (2): 110–17. doi:10.1111/nure.12001. PMID 23356638.

- ^ Hankey, Graeme J.; Wardlaw, Joanna M. (2008). Clinical neurology. London: Manson. p. 466. ISBN 978-1840765182. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ Schwartz, William (2012). The 5-minute pediatric consult (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 535. ISBN 9781451116564. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2020-05-09.