User:Niado/sandbox

History[edit]

Dogs resembling the Great Dane have been seen on Egyptian monuments dating back to 3,000 BC.[1]

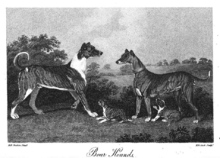

Extremely large boarhounds resembling early Great Dane type appear in ancient Greece, in frescoes from Tiryns dating back to 14th-13th centuries BC.[2][3][4] The large boarhound or Molossian hound continues to appear throughout ancient Greece in subsequent centuries right up to the Hellenistic era.[5][6][7][8] Later on the great hound of Epirus becomes known as the Suliot Dog.[9][10][11] The authors David Hancock, John William Carleton, Charles Hamilton Smith & Sir William Jardine, Desmond Morris, W.H. Lizards (quoted by Juliette Cunliffe), Μ.Β.Wynn (quoted by Desmond Morris), Lord Truro (quoted by D. Hancock) all mention the great descendant of the Molossian hound, the Suliot dog and specific imports from Greece (two engravings exist illustrating these dogs [12][13]) that were used in the 18th century to increase the stature of the boarhounds in Austria and Germany & the wolfhounds in Ireland. [14][15][16] [17] [18] [19] [20]

Bigger dogs are depicted on numerous rune stones in Scandinavia, on coinage in Denmark from the 5th Century AD and in the collection of Old Norse poems, known in English as Poetic Edda. The University of Copenhagen Zoological Museum holds at least seven skeletons of very large hunting dogs, dating from the 5th Century BC going forward through to the year 1000 AD.

16th - 18th Century[edit]

In the middle of the 16th Century the nobility in many countries of Europe imported strong, long-legged dogs from England, which descended from crossbreeds between the English Mastiff and the Irish Wolfhound. They were dog hybrids in different sizes and phenotypes and no formal breed in the understanding of our days.[21] This type was called "Englische Docke", "Englische Tocke" - later written and spelled: "Dogge" - or "Englischer Hund" in Germany. The name originally meant simply "English dog". In other continental European countries arosed similar terms, too. The English word "dog" became after time the term for a molossoid dog in Germany[22] and in France,[23] too.

Since the beginning of the 17th Century, these dogs were bred independent on the courts of the German nobility.[24][25]

″Es kommet solche grosse Art von Hunden eigentlich aus Engelland oder Irrland, welche grosse Herren vor diesem anfänglich aus solchen Ländern mit vielen Unkosten haben bringen lassen, sie werden aber jetziger Zeit nicht mehr so weit gehohlet, sondern in Teutschland an grosser Herren Höfen von Jugend auf erzogen und zur Pracht erhalten, auch nach ihrer Grösse, guten Gewächs, Schönheit und Farben unterschieden und aestimieret.″[26]

″Such big kind of dogs comes actually from England or Ireland, which have been initially brought to big nobleman from those countries with much costs, but they were in this time not more fetched so far-off from, but in Teutschland (Germany) at the courts of big nobles from youth on nurtured and in finery obtained, and in size, good growth, beauty and colors distinguished and held in esteem.″

The name "Englische Dogge" stayed common till into the 19th Century.[27] In the course of the centuries this designation wasn't anymore understood as designation of origin, but should characterise this dog type as something special and distinguish it's idiosyncrasy. In this way were the kennels named as "englische Stall" (English stable) and the (local) keepers "englische Hunds-Jungen' (English dog-keepers [boys]).[21] Similarly were to other dog types given the names of other countries, without that there had to be a real relationship or ancestry,[28]

They were kept as dogs for the hunt on bear, boar and deer at princely courts, where the most beauty and strongest as 'Kammerhunde" (chamber dogs) with gilded collars stayed at night in the bedchamber of their lord. For the dogs were made big sleeping-places with paddings or bearskins. They should protect the sleeping prince against assassins. The second most beauty were named "Leibhunde" (favourite dogs) and gets silvered collars. [29][30] All the rest remained the "Englische Docken".[31] They get no special collars and were kept in the "englische Stall" (kennel).

This grading of in three tiers "separated" and "esteemed" dogs, gives reason to think, that the pure breeding was done in this way and that it was taken more care to the more purebred animals. But the ordinary "Englischen Docken" were so valuable, too, that they weren't to reckless utilized.

On the hunt for boar were at first the Saufinder sent out, they had find the wild hogs and to draw attention of the Saurüden to these by barking. The Saurüden drove the wild hogs out of the forest on a clearing. This part was the most dangerous and very lossy, which is why this dog type wasn't really bred.[32] If available, could come in addition the Courshunde, with what were mostly meant mixed breed dogs of different dog types. Mix-breeding of different dog types was done often in earlier times. Another term for mixed breed dogs of this kind was Blendlinge.

Not until then were the "Doggen" chased on the wild hogs,[33] which had knock them down and seize[34] them, until it was killed by a huntsman. For their protection wore they armors of thick lined cloth, which were at the side of the belly strengthened with whalebone.

On the hunt for bears were at first the Baerenbeisser's used, to weary the bear. After that were made use of the "Doggen" as on the hunt on boar.

When the hunting customs changed, particularly because of the use of firearms, the Danes were no longer needed. Many of those involved dogs types, such as the Saufinder or the Baerenbeisser disappeared. Also, the Great Dane became more rare and was kept only as a dog of hobby or luxury. Mainly in rural Württemberg it stayed as the Ulmer Hund or Ulmer Dogge.

19th Century[edit]

In the mid-19th Century it found with beginning of the pedigree breeding and founding of kennel clubs under the names 'Ulmer Dogge" und "Dänische Dogge" bigger interest, again. In the English speaking countries was it originally denoted as "German boarhound". In the studbook of England was the name "German boarhound" not before 1894 changed in "Great Dane".[35] Some German breeders tried to introduce the Names "German Dogge" or "German Mastiff" on the English market, because this breed should be marketed as a dog of luxury and not as a working dog. Nonetheless these names were not accepted.[24] "Dogge" sounded to strange and on the upcoming rivalries of nations no one wanted to have a German dog or even a so-called "Reichshund".

Instead the name "Great Dane" became popular, after the "grand danois"[36] in Buffon's Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière in 1755. But it's dubious if this was ever a molossoid doge type or if such dog as a constant dog type existed. In the same work of Buffon is another dog depicted, the "le dogue de forte race".[37] Translated in English it means "the Mastiff of the heavy breed" [38] and it could be translated in German with "Grosse Dogge" (Great Mastiff), which was the type of the "English dog" on the continent, of Mastiff and Irish Wolfhound origin, in Germany known as "Englische Docke".

Around the turn of the 18th century existed in Germany several landraces or regional breeds of this "Englische Dogge". The southern variation was known as Ulmer Dogge (Mastiff from the Ulm area), mostly massive, the color black or white and black "getigert" (spotted or mantle).[39] And in northern and middle Germany the dogs were often (so) called Dänische Dogge (Danish Mastiff), which were often fawn, isabelle or brindled ("gestromt") colored and were mostly a bit minor in size and weight compared to the Ulmer landrace. Other generally names were Saupacker ("boar-seizer") or Hatzrüde ("chasing dog"). The separation in landraces was common for all "breeds" of dogs in this times, because no formal standardized breeds existed.

On the first bigger German dog show in 1863 in Hamburg were eight as "Dänische Doggen" and seven "Ulmer Doggen" denoted dogs exhibited. This separation was iterated in 1869 on the dog show in Altona. Though none of this dogs came from Denmark or had a stammer from there. First in 1876 the adjudicators suggested to the breeders to agree among themselves on the name "Deutsche Dogge" (German Mastiff), because the dogs were scarcely to distinguish.[40]

On 12 January 1888 in Berlin was the "Deutsche Doggen Club" founded. It was first Kennel Club in Germany ever.[41]

Nevertheless the name "Deutsche Dogge" became common in Germany only after considerable time. The breeder Otto Friedrich, from which "Tyras II.", the successor of Bismarcks favourite dog came from, sold still in 1889 both varieties under their former names.[42] Leonhard Hoffmann denoted it still in year 1900 the "Ulmer Dogge", "today's so called Deutsche Dogge".[43]

Otto von Bismarck owned Danes since his youth. He wasn't able to leave back his Dane "Ariel", when he left for Göttingen in 1832 to study law. Later, in the time of German Empire, were this animals occasionally denoted as Reichshunde.[44]

A claim of other origin of the breed[edit]

It can be assumed that Frederick VII, between 1848 and 1863 the King of Denmark, Duke of Schleswig and Duke of Holstein read about Buffon's "grand danois". He gave order to search for suitable dogs and to establish a breed if possible. With that was commissioned a councillor of state Klemp. In a prize essay "The mammalians of the Danish and Norwegian state" from 1834 the Danish professor Melchior had described the "Large Danish dog, the butchers dog". Dogs from this kind were collected in Schleswig-Holstein and Denmark to start this breed. This breed was later named as "King-Fredrick-VII-Breed" or the "Jägerpri(i)s" after his hunting château. Later were this breed brought into the Zoological Garden of Copenhagen / Zoological Museum of Kopenhagen. The most representative male dog was the famous "Holger", who fathered the most of the puppies.[45][46]

The breed of the large, yellow Danish dog was a refinement of well-shaped and sturdy butchers dog.

This breed must have become rare in later times.[47]

"Around 1855 decided the possessor of Broholm, a von Sehested, to collect the remains of the Danish dog, to preserve the breed and to spread this dog generally in this country. This task wasn't easy, because not much breed-material existed and it wasn't fully clear how this dog had to look like.[..]"

However this doge type was further developed. "Puppies were given for free to people in Denmark, who were willingly to help this undertaking. So arose the Broholmer dog, over 20 years were spread more than 150 puppies in the country."[48]

In 1886 at a dog show in Copenhagen was established a breed standard, but this dog was named "Large Danish dog", too.

With that is shown, what's the truth in the claim, the Great Dane would be a breed of Danish origin. Why should the breed of this Large Danish dog, butcher's dog or the Broholmer have been undertaken, when there had been existed a "grand danois" with the attributes of the German breed? Because there was none. In the late 18th and the early 19th Century existed no Buffon's "grand danois" and no German "Englische Dogge" in Denmark.[49] If a breed had existed, it was extincted before.

Nonetheless it is very probable, that the Danish nobility in 16th and 17th Century imported "English dogs", too, as the nobles in most continental European countries did. And it isn't improbable, that the Broholmer is a far cousin of the German "Dogge", because it may be the descendant of a Danish "English dog".

The "Large Danish dog" gets later the name "Broholmer" from the estate of Broholm, but some Danish breeders, which had bought "Dogge"s in Germany, claimed at the end of the 19th Century that these were the "Large Danish dog" of Danish origin. This claim was strictly refused.

In Germany, of course, the position, that the Great Dane is a German breed, was never abandoned. This continued with the rise Nazi Germany. In December 1936 the Danish national kennel association "Dansk Kennel Klub" was put on notice in writing that Germany demanded the cessation of usage of any words not identifying the hound as of German origin on the forthcoming General Assembly of the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) in Paris 22 July 1937. After World War II The Secretary General of the FCI Baron A. Houtart writes a letter, copied to the Danish national kennel association. The letter is dated 15 November 1948 and says in French:

"Pour la F.C.I. cette race a toujours été et reste encore une race nationale danoise ; seul le standard déposé par le Dansk Kennelklub est officiel à ses yeux"

"As far as the FCI is concerned, this breed [The Great Dane] has always been and shall remain a Danish breed; only the standard provided by the Danish national kennel association is the official one in our view." The original letter is kept with the FCI and the Great Dane Club of Denmark.

However, today the FCI designates the Great Dane as German breed.[50] The Broholmer is known as the Mastiff of Danish origin.[51] In 2010 the Danish Kennel Club challenged this estimation.[52]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

AKCwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Mycenaean Fresco wall painting of a Mycanaean with horse & wild boar hunting dog from the Tiryns, Greece. 14th - 13th Century BC. Athens Archaeological Museum. | Photos Galler...

- ^ Tiryns Fresco | Flickr - Photo Sharing!

- ^ https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0b/Tiryns_fresco.JPG

- ^ Thaumazein: The Hunt For The Calydonian Boar

- ^ The Hind of Ceryneia Diana's Pet Deer | Flickr - Photo Sharing!

- ^ http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/Herakles/Hpix/1992.06.0122.jpeg

- ^ http://www.pbase.com/dosseman/image/28792061 Pergamon

- ^ Suliot Dog

- ^ The Natural History of Dogs: Canidae Or Genus Canis of Authors ; Including ... - Charles Hamilton Smith, Sir William Jardine - Google Books

- ^ The Sporting review, ed. by 'Craven'. - Google Books

- ^ http://www.davidhancockondogs.com/archives/archive_729_779/images/734/734D%20SULIOT%20DOG.jpg

- ^ Art and History - Suliot dog - Molosser Dogs Gallery

- ^ 1840, Dogs, Canidae or Genus Canis of Authors, including The Genera Hyaena and Proteles, Vol. II., Mammalia Vol.X, by Lieut-Col. Chas Hamilton Smith, with Portrait and Memoir of Don Felix D'azara|http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AgsOAAAAQAAJ&dq=Naturalist's%20Library%20PARROTS%20jardine%20BEWICK&pg=PR5#v=onepage&q=Suliot&f=false

- ^ Archive

- ^ Archive

- ^ Archive

- ^ http://www.davidhancockondogs.com/archives/archive_240_309/276.html Great Danes Giant Hounds by D. Hancock

- ^ The Sporting review, ed. by 'Craven'. - Google Books

- ^ Morris, Desmond. Dogs - The Ultimate Dictionary of Over 1,000 Dog Breeds. Ebury Press, 2001. ISBN0-09-187091-7. Page 618.

- ^ a b Ludwig Beckmann in: Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, S. 6

- ^ the German standard term for "dog" is "Hund"; the term "Dogge" is only in use for dogs of the mastiff-type

- ^ the French standard term for "dog" is "chien"; the term "dogue" is only in use for dogs of the mastiff-type

- ^ a b Ludwig Beckmann in: Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, S. 7

- ^ German: Johann Täntzer in: "Jagdbuch oder der Dianen hohe und niedrige Jagdgeheimnisse", Abschnitt: "Von den Englischen Hunden.", Kopenhagen, 1682, (written in German): "Jetziger Zeit werden solche Hunde jung an Herrenhöfen erzogen, und gar nicht aus England geholet.“ English translation: Johann Täntzer in: "Hunting book or Dianas high and low hunting secrets", Copenhagen, 1682, Heading: "On the English dogs" In this time were such dogs young nurtured at nobleman's courts, and not anymore fetched from England." cited in Ludwig Beckmann in: Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, p. 7

- ^ Johann Friedrich von Flemming in: Der vollkommene teutsche Jäger., Abschnitt: "Von denen Englischen Docken." (heading: On the English Dogge's) , Leipzig, 1719, Bd. 1, p. 169 (Digitalistat of the HAB Wolfenbüttel)

- ^ for example: Ge. Frz Dietr. aus dem Winckel in: Handbuch für Jäger, Jagdberechtigte und Jagdliebhaber, F. A. Brockhaus, 1858, Bd. 1, S. 188: "Englische Doggen. Dies ist die stärkste Hunderasse(..)" english:„English Dogge's [Mastiffs]. This is the strongest breed of dogs(..)" (Digitalisat books.googl.de)

- ^ Das Buch vom gesunden und kranken Hunde. Lehr- und Handbuch für das Ganze der wissenschaftlichen und praktischen Kynologie. Wien 1901, p. 144 (Digitalisat Internet Archive)

- ^ Johann Täntzer in: "Jagdbuch oder der Dianen hohe und niedrige Jagdgeheimnisse", Abschnitt: 'Von den Englischen Hunden.", Kopenhagen, 1682, diverse Neuauflagen: - cited in Ludwig Beckmann in: Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, p. 9 English translation: Johann Täntzer in: "Hunting book or Dianas high and low hunting secrets", Copenhagen, 1682, Heading: "On the English dogs" cited in Ludwig Beckmann in: Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, P. 9

- ^ in another source: Johann Friedrich von Flemming in: Der vollkommene teutsche Jäger., Abschnitt: "Von denen Englischen Docken.", Leipzig, 1719, Bd. 1, p. 169 are the collars of the "Cammer-Hunde" (chamber dogs) upholstered with velvet and spangled with letters of silver and the collars of the "Leib-Hunde" (favourite dogs) are upholstered with plush and spangled with brass letters

- ^ Johann Friedrich von Flemming in: Der vollkommene teutsche Jäger., Abschnitt: "Von denen Englischen Docken." , Leipzig, 1719, Bd. 1, p. 170 (Digitalistat HAB Wolfenbüttel)

- ^ Saurüden were mostly taken from the Schafrüden, the live stock guarding dogs of this time. They had to been placed by the peasants to the nobles for the hunting season. This dogs needs no special education, but the peasant who had to place a Saurüden and placed a weak dog or one without hunting instinct had to pay a fine.

- ^ origin of the more generally term Hatzrüde ("chasing dog")

- ^ origin of the more generally term Saupacker ("boar-seizer, boardog")

- ^ S. William Haas in: Great Dane: A Comprehensive Guide to Owning and Caring for Your Dog (Series:Comprehensive Owner's Guide), Kennel Club Books, 2003, S. 13

- ^ depiction of Buffon's grand danois (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- ^ depiction of Buffon's le dogue de forte race (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- ^

The french sentence by Buffon: Le dogue produit avec le mâtin un chien métis que l'on appelle dogue de forte race, qui est beaucoup plus gros que le vrai dogue, ou dogue d'Angleterre, et qui tient plus du dogue que du mâtin.

- Buffon's natural history of the globe, and of man, beasts, birds, fishes, reptiles, and insects, P. 289, (Google books)

- Buffon's Natural history of man, the globe, and of quadrupeds, Bd 1-2 Leavitt & Allen, 1857, P. 209

- Another more right translation:

- ^ outdated: Duden, Keyword: "getigert" in German, retrieved 2013-07-23

- ^ Ludwig Beckmann in: Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, S. 14

- ^ Grandstanding of the Deutsche Doggen Clubs 1888

- ^ Otto Friedrich in: Des edlen Hundes Aufzucht, Pflege, Dressur und Behandlung seiner Krankheiten., 7. Auflage, 1889, p. 40 and p. 45

- ^ Leonard Hoffmann in: Das Buch vom gesunden und kranken Hunde. Lehr- und Handbuch für das Ganze der wissenschaftlichen und praktischen Kynologie., Vienna 1901, P. 144 ff (Digitalisat at Internet Archive)

- ^ In German: Wolfgang Wippermann: Biche und Blondi, Tyras und Timmy. Repräsentation durch Hunde. In: Lutz Huth, Michael Krzeminski: Repräsentation in Politik, Medien und Gesellschaft, S. 185-202. Königshausen & Neumann, 2007 ISBN 3-8260-3626-3 [1]

- ^ Ludwig Beckmann in: Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, p. 50

- ^ Das Buch vom gesunden und kranken Hunde. Lehr- und Handbuch für das Ganze der wissenschaftlichen und praktischen Kynologie. Wien 1901, p. 181 (Digitalisat Internet Archive)

- ^ The remnants of the "Jaegerpris" and the breed of Broholm melded together in one breed, the Broholmer, after 1895.

- ^ From a letter of the Hofjaegermeister von Sehested, in this time the owner of the breed, relative of Count Niels Frederik Bernhard von (of) Sehested, cited in: Ludwig Beckmann Geschichte und Beschreibung der Rassen des Hundes, Bd 1, 1895, p. 51

- ^ Das Buch vom gesunden und kranken Hunde. Lehr- und Handbuch für das Ganze der wissenschaftlichen und praktischen Kynologie. Wien 1901, p. 186 (Digitalisat Internet Archive)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

FCIwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ria Hörter in: onze HOND 12/2007, article: "Deense rassen (Danish breeds)", p. 120 (in Dutch) (pdf)

- ^ Minutes of the FCI General Committee Madrid, 24-25th February 2010, P. 6