User:Pingnova/sandbox/Mahkato Wacipi

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

Mahkato Wacipi (English: Blue Earth Powwow) is an annual powwow held at Land of Memories Park (Dakota Wokiksuye Makoce) in Mankato, Minnesota. It was founded in the late 1950s by Prairie Island Indian Community elder Amos Owen and white Mankato businessman Bud Lawrence as part of an effort to repair relations between Dakota people and European-descent immigrants following the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862. For this reason the wacipi is known as a "reconciliation powwow." The wacipi is unique among powwows for its focus on non-Native outreach and education, being hosted outside an Indian reservation, and the Dakota-white alliance of the founders.[1]

Etymology

[edit]Mahkato is Dakota for "Blue Earth" (the location of the event) and wacipi (wačhípi[2]) means "we all dance", and is sometimes used in place of powwow. Powwow and wacipi are not necessarily synonymous, as historian Loren Dean Boutin notes: "A powwow can and usually does have a wacipi within it".[cite 1]

The event is also referred to as Dakota Mahkato Mdewakanton Wacipi[1] and the Mankato Reconciliation Powwow (or simply "the Mankato Powwow"). The Dakota language name is the most publicized.

Mission of reconciliation

[edit]Powwows are typically gatherings which focus on perpetuating Native culture among Native people. While non-Natives are frequently encouraged to attend, they are not a focus. Uniquely, Mahkato Wacipi focuses on non-Native outreach.

“[It’s about] education, education and a little bit more in the area of understanding. Understanding that there are many diverse cultures and there are many races and many walks of people and that we can all share within all of our cultures.”

— Londel Seaboy, Arena Director for the 51st Mahkato Wacipi[3]

Education and culture sharing are a core part of the wacipi. The first day is Education Day, whose attendees consist mainly of primary, secondary, and post-secondary students from local schools. Students participate in cultural activities such as moccasin games and bracelet weaving, attend oral history and legend sessions, and watch narrated demonstrations of wacipi dance and other performance.

Education Day was instituted in 1987 as part of statewide efforts towards reconciliation. As a partnership between the wacipi committee and all local schools, the day originally focused on third grade classes and has since expanded. From 1987 to 2000, the wacipi reports "over 10,000 children, teachers, parents and Native American resource persons have participated in [this] unique direct cultural exchange education program".[1]

Throughout the weekend, Native and non-Native volunteers are available to answer questions at a centrally located Education Tent. Volunteers also host education circles: attendees sit in a circle led by Native volunteers who verbally relate the story of the wacipi's founding and encourage questions from attendees.

Wacipi history

[edit]Prior to the first Mahkato Wacipi, the group who later founded the event focused on placing Native perspectives in local schools. In the 1960s, most local history was taught from a white settler perspective and included misinformation on Native people perpetuated by those one-sided historical accounts, such as that Native people were all "inhumane savages".[cite 2] Wacipi founders Amos Owen and Bud Lawrence noticed this and recruited Dakota people to relate oral history during local history modules in wider Mankato-area school districts. Their goal was go "replace misinformation" and demonstrate that Native people were "sensitive human beings but simply with a different culture."[cite 2] Two frequent oral historians were hereditary Dakota chief Ernie Wabasha and his wife Vernell, who late became instrumental in the annual wacipi.

Several distance walks and runs occurred between Lawrence and Owens's first meeting that resulted in the wacipi. Participants included Lawrence, Owen, Jim Buckley, Barry Blackhawk, Merrill Claridge, Carie Robb, and Marilyn Hardt. Distance walking and running is a traditional Dakota sport and can be part of ceremonies. Many of the walks were to honor Amos, who was a renowned spiritual leader with devoted followers. The walks spanned more than 10 miles at a time. Several of the walks ended at Prairie Island Indian Reservation where the participants were received by leaders on horseback and honored at a wacipi.

During one of these walks, Lawrence and Blackhawk had the idea to throw a wacipi to raise funds for YMCA programs they were involved in. Owen was consulted for his spiritual leadership, and he agreed a wacipi was a good idea, although he had a bigger vision: that a wacipi could "be a way of bringing the Dakota back to an area that has once been very important to them, and it might also be a way of healing the fractured relationships between the local white communities and the Dakota people."[cite 3]

At the time, the greater Mankato area was akin to a sundown town for Native people, many of whom tried to only pass through the area during daylight and never stay overnight. Wacipi organizers were worried about public reception—and whether anyone, Native or white, would even show up. The first wacipi was badly attended and operated at a loss of $1,200 which was covered by the Mankato YMCA Men's Club, one of the sponsors.

When Lawrence expressed doubt that the wacipi would be successful after low attendance the first day, Owen replied: "Don't worry. Tomorrow morning the Dakota will come." Friday there were no musical performers and only one dancer, who was also one of the vendors. Saturday ended with the event field full of campers and vendors, with a large contingent of dancers eager to safely dance in Mankato for the first time. About 100 non-dancer non-vendor attendees were logged. While a small number, Vernell Wabasha is recorded as complaining she had no time to watch the wacipi because of the busyness of the ticket booth.[cite 4]

Despite the financial concerns, some considered the first Mahkato Wacipi a success because it was the first time Native people were publicly welcomed back to the Mankato area in 110 years. Native people had been officially and unofficially banned for more than a century. In the late 1800s the locality enacted an ordinance that would pay $25-$200 for any Native scalp to any white resident as a way to eject Natives totally from the area.

There was no wacipi the next year in 1973. The financial losses of the first had previous sponsors wary and many had not conceived of it as an annual event. Previous organizers spent the year discussing lessons from the first wacipi and fundraising for a second. The 1974 Mahkato Wacipi had new sponsors who offered much less funding and the committee raised $500 itself. Despite lack of funds, many local businesses contributed services. The City of Mankato reached out before the wacipi committee could and donated park space and facilities for the weekend of its own accord. The community was optimistic about the mission of the wacipi and enjoyed the economic benefit the visitors brought. Bill Basset, then-city manager of Mankato, became a core supporter of the wacipi each year and a close colleague to Owen.

The wacipi became an annual event which grew in attendance and funding as the years went on. Many local businesses became yearly funders and the news of the event and its mission spread to Native and white communities across the region. The wacipi reached financial stability when tribes began donating profits from newly established Indian casinos and government grants for cultural activities became available.

The event

[edit]

The wacipi is held annually on the first full weekend of September. It spans the full weekend beginning Friday at 9:00 AM and ending Sunday at 5:00 PM. The final dance begins at 7:00 PM each night, though the end time varies and can go as late as 11:00 PM.

The performances and ceremonies are typical of a powwow.

A rotation of powwows are held across North America each year and are known as the "powwow circuit". Many wacipi attendees end their yearly circuit at Mahkato Wacipi, which being the third full weekend of September is typically the last Minnesota outdoor powwow of the season.

| Friday | |

| 9:00 AM | Education Day |

| 5:00 PM | Meal |

| 7:00 PM | Grand Entry |

| Saturday | |

| 9:00 AM | Flag raising |

| 11:00 AM | Honoring |

| 12:00 PM | Meal |

| 1:00 PM | Grand Entry |

| 5:00 PM | Meal |

| 7:00 PM | Grand Entry |

| Sunday | |

| 9:00 AM | Royalty Contest |

| 12:00 PM | Meal |

| 1:00 PM | Grand Entry |

| 5:00 PM | Closing Ceremony |

Events called Specials which are performed by visiting families are scheduled throughout the weekend with registration required by the preceeding night. They are typically scheduled between 9:00 AM and 12:00 PM.

Education Day

[edit]A core part of the wacipi are its educational activities. The first day is Education Day and consists mainly of visiting students from local primary and secondary schools.

Specials

[edit]

Specials are performances by visiting familial groups to honor events such as births, deaths, graduation, and spiritual milestones. There are breaks in the daily schedule to allow for Specials, which are usually scheduled that weekend and not in advance. Specials can incorporate singing, dancing, speeches, prayer, and other performance.

The major Specials performed at Mahkato Wacipi are:

- Eagle Feather (Fallen Warrior): Veterans perform this ceremony to retrieve Eagle (Wambdi) feathers that have fallen to the ground. Visitors are asked not to touch fallen feathers and to alert the emcee.

- Giveaways: Family groups collect items all year to award at the wacipi, which are given away at this Special. Gifts are given to those who especially helped the family and sometimes even non-Native strangers. Children are frequently gifted special items related to life and spiritual milestones.

- Naming Ceremony: An elder or spiritual leader bestows a spiritual name to an individual, typically on behalf of a family group. Giveaways and Honor Songs follow in celebration.

- Honor Songs: Sung for many reasons, including after Eagle Feather, Naming Ceremony, or a Giveaway, Honor Songs commemorate milestones, especially death. Relatives who have passed in the previous year are frequently commemorated and spectators are usually invited to dance, sing, or shake hands with the family. One Honor Song is scheduled into the main event each year for the person that year's wacipi is dedicated to the memory of.

The arena

[edit]

The circular grounds for dancing are referred to as the arena. At Land of Memories Park, a large permanent arbor was constructed to shade spectators and designate an area just for dancing. The open pavilion is a circle divided into five sections painted the four colors of the medicine wheel.[4] Spectators can sit on the grass, in their own chairs, on stadium seating under the arbor, or stand.

The arena grounds are blessed by traditional grass-style dancers prior to the day's events. Since the ground is considered sacred for the duration of the wacipi, spectators are asked to refrain from swearing, spitting, and unruly behavior. A major rule in powwows across the world, including Mahkato Wacipi, is to not walk across the arena grounds unless you are dancing.

The wacipi (dance) portion of the powwow is contained in the arena. Outside the arena are vendors, picnic tables, toilets, and campsites. The emcee stays at the head of the arena all day to announce events, special notices, direct dancers and music, and provide entertainment.

Cultural conduct

[edit]Rules of conduct are enforced at the wacipi, especially in light of its mission of reconciliation and healing.

Because it intentionally welcomes non-Natives with no previous powwow experience, the emcee narrates conduct expectations and event history during each performance. An education tent at the entrance of the wacipi grounds is staffed with knowledgeable volunteers who answer questions and host education circles throughout the day. Volunteers are Native elders and non-Native Nicollet County Historical Society staff. Reference materials such as books, exhibits, and posters are also available.

The emcee and event literature expressly forbids recording or photos of Honor Songs, prayers, and Naming Ceremonies. There may be other times the emcee announces photos are forbidden. Audio recording is forbidden when video recording is.

Commercial photography, videography, or audio recording is disallowed without staff consent.

Mahkato Wacipi is a sober event which forbids drugs or alcohol on the grounds, including intoxicated individuals. Security and the sheriff's department enforce the policy.

History

[edit]

Since the expulsion of Dakota people from Minnesota Territory following the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, the cities of Mankato and New Ulm, Minnesota had been especially unwelcoming places to Native people of any kind. In what remains the largest mass execution in the United States, 38 Dakota men were hanged simultaneously in downtown Mankato after several months in an internment camp. The spectacle was met with cheering from a large crowd of settlers and the mass grave was later robbed. Cut Nose is the most well-known of those hung in Mankato because his body was dissected by the Mayo family, some of the most influential physicians in pioneer America. His remains were retained and displayed by Mayo Clinic until xxxx. Parts of his remains were repatriated, though many remain in the clinic's collections.

While only the Eastern Dakota took part in the war, businesses interested in acquiring more land and fearful civilian settlers affected by the battles wanted all Native people removed from the territory. Thus when the surviving Dakota non-combatants were interned at the Fort Snelling concentration camps, so were the Winnebago, who had not participated in the war. The camps closed in 1863 when prisoners were transported by boat and on foot to sites in current day South Dakota and Iowa. This was considered the end of Dakota inhabitation of Minnesota by white authorities, who instituted scalp bounties for the tops of Dakota skulls, many of which paid several times more than the yearly wage of even a highly paid soldier. The bounties were even opened to civilians, a then unheard of practice in Minnesota Territory.

Mahkato Wacipi historian Loren Dean Boutin in The Mankato Reconciliation Powwow (2012) notes that the civilian scalp bounty perpetuated an environment where every white person was an active danger to a Native person, unlike in the past when only white authorities such as soldiers were monetarily compensated to fight with Natives. Most people were very poor and struggled to meet their basic needs at the time, which made scalp bounties too attractive to ignore.

When a soldier's pay for a month of service was ten dollars, and the cost of a horse was twenty dollars, the collectable bounty for an Indian scalp was seventy-five dollars.

— Loren Dean Boutin, The Mankato Reconciliation Powwow (2012), p. viii

Chief Little Crow III, who had initially opposed to the war due to overwhelming settler numbers, but ultimately agreed to lead the battle, was murdered in 1863 while foraging berries. A civilian farmer and his son shot and killed the chief for the scalp bounty and reported no provocation.[5] No scalp bounty existed in Minnesota at the time, which made the killing a murder under state law, but the farmer was paid $75 for Little Crow's scalp, and later $425 when it was revealed the body was of Chief Little Crow. Just after the murder, an adjutant general of the Minnesota militia authorized a $25 bounty for military scouts and a $75 bounty for civilians, who were not usually contracted or paid by the army. The state further raised the civilian bounty to $200 and classed bounty hunters as "independent scouts," rather than military scouts. The militia paid at least 5 scalp bounties, though the exact number is uncertain and may be less.

Blue Earth County, where Mankato is located, had an additional $25 scalp bounty ordinance, which was raised to $200 in 1865. Historians such as Boutin are unsure how many bounties were paid in Blue Earth county, if any, due to poor recordkeeping and loss of archives, though Boutin notes the spirit of the ordinance was sufficient to deter Native people for decades. Combined with state and miltia bounties for civilians, as well as overwhelmingly negative public sentiment towards Native people following the war and the spectacle of mass hanging, rejection of and violence towards Native people became ingrained in the wider Mankato-area public.

Post-war

[edit]

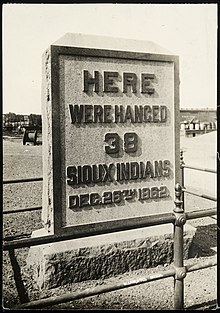

In 1912 a controversial granite monument like a large tombstone was erected at the site of the mass hanging which stated "Here were hanged 38 Sioux Indians, Dec. 26th 1862". No one publicly claimed the monument nor was the intent ever publicized. Some residents saw it as a distasteful boast, some saw it as a neutral declaration of fact, some saw it as honoring those hanged, and others saw it as a victory speech. This renewed public interest in the aftermath of the 1852 war, both postive and negative, particularly in publications such as the local news. The monument was frequently splattered with red paint resembling blood until it mysteriously vanished after removal by the city in 1971. Opinions garnered by the monument continued to warn Native people away from the greater Mankato area and the war was never far from the minds of settler-descedents and Natives.

Following the removal of the monument, friends Amos Owen and Bud Lawrence resolved to attempt a reconciliation powwow. Their vision came to fruition the next year in September of 1972.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Boutin 2012, p. 21

- ^ a b Boutin 2012, p. 16

- ^ Boutin 2012, p. 22

- ^ Boutin 2012, p. 24

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Purpose and History | Mahkato Mdewakanton Association". Mahkato Wacipi Commi. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Dakhód Iápi Wičhóie Wówapi (in Dakota). Dakhóta Iápi Okhodákičhiye. 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Jackson, Kyla (September 18, 2023). "Community gathers for 51st anniversary of Mahkato Wacipi Pow Wow Event". https://www.keyc.com.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Press, The Free (May 30, 2020). "Ask Us: Powwow arbor colors filled with symbolism". Mankato Free Press.

- ^ LC wiki page info (1970s) differs from LDB (2012), check this

Bibliography

[edit]- Boutin, Loren Dean (2012). The Mankato Reconciliation Powwow. Saint Cloud, Minnesota: North Star Press of St. Cloud, Inc. ISBN 9780878396290.

External links

[edit]