Variational autoencoder

| Part of a series on |

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

In machine learning, a variational autoencoder (VAE),[1] is an artificial neural network architecture introduced by Diederik P. Kingma and Max Welling, belonging to the families of probabilistic graphical models and variational Bayesian methods.

It is often associated with the autoencoder[2][3] model because of its architectural affinity, but with significant differences in the goal and mathematical formulation. Variational autoencoders allow statistical inference problems to be rewritten (such as inferring the value of one random variable from another random variable) as statistical optimization problems (i.e find the parameter values that minimize some objective function).[4] They are meant to map the input variable to a multivariate latent distribution. Although this type of model was initially designed for unsupervised learning,[5][6] its effectiveness has been proven for semi-supervised learning[7][8] and supervised learning.[9]

Architecture

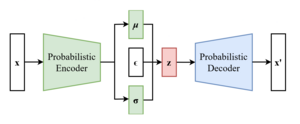

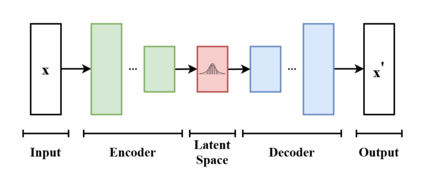

In a VAE the input data is sampled from a parametrized distribution (the prior, in Bayesian inference terms), and the encoder and decoder are trained jointly such that the output minimizes a reconstruction error in the sense of the Kullback–Leibler divergence between the parametric posterior and the true posterior.[10][11][12]

Formulation

From a formal perspective, given an input dataset characterized by an unknown probability distribution , the objective is to model or approximate the data's true distribution using a parametrized distribution having parameters . Let be a random vector jointly-distributed with . Conceptually will represent a latent encoding of . Marginalizing over gives

where represents the joint distribution under of the observable data and its latent representation or encoding . According to the chain rule, the equation can be rewritten as

In the vanilla variational autoencoder, is usually taken to be a finite-dimensional vector of real numbers, and to be a Gaussian distribution. Then is a mixture of Gaussian distributions.

It is now possible to define the set of the relationships between the input data and its latent representation as

- Prior

- Likelihood

- Posterior

Unfortunately, the computation of is expensive and in most cases intractable. To speed up the calculus to make it feasible, it is necessary to introduce a further function to approximate the posterior distribution as

with defined as the set of real values that parametrize .

In this way, the overall problem can be easily translated into the autoencoder domain, in which the conditional likelihood distribution is carried by the probabilistic decoder, while the approximated posterior distribution is computed by the probabilistic encoder.

ELBO loss function

As in every deep learning problem, it is necessary to define a differentiable loss function in order to update the network weights through backpropagation.

For variational autoencoders the idea is to jointly minimize the generative model parameters to reduce the reconstruction error between the input and the output, and to have as close as possible to .

As reconstruction loss, mean squared error and cross entropy are often used.

As distance loss between the two distributions the reverse Kullback–Leibler divergence is a good choice to squeeze under .[1][13]

The distance loss just defined is expanded as

At this point, it is possible to rewrite the equation as

The goal is to maximize the log-likelihood of the LHS of the equation to improve the generated data quality and to minimize the distribution distances between the real posterior and the estimated one.

This is equivalent to minimizing the negative log-likelihood, common practice in optimization.

The loss function so obtained, also named evidence lower bound loss function, shortly ELBO, can be written as

Given the non-negative property of the Kullback–Leibler divergence, it is correct to assert that

The optimal parameters minimize this loss function. The problem can be summarized as

The main advantage of this formulation relies on the possibility to jointly optimize with respect to parameters and .

Before applying the ELBO loss function to an optimization problem to backpropagate the gradient, it is necessary to make it differentiable by applying the so-called reparameterization trick to remove the stochastic sampling from the formation, and thus making it differentiable.

Reparameterization

To make the ELBO formulation suitable for training purposes, it is necessary to slightly modify the problem formulation and the VAE structure.[1][14][15]

Stochastic sampling is the non-differentiable operation through which it is possible to sample from the latent space and feed the probabilistic decoder.

The main assumption about the latent space is that it can be considered to be a set of multivariate Gaussian distributions, and thus can be described as

Given and defined as the element-wise product, the reparameterization trick modifies the above equation as

Thanks to this transformation (which can be extended to non-Gaussian distributions), the VAE becomes trainable and the probabilistic encoder has to learn how to map a compressed representation of the input into the two latent vectors and , while the stochasticity remains excluded from the updating process and is injected in the latent space as an external input through the random vector .

Variations

Many variational autoencoders applications and extensions have been used to adapt the architecture to other domains and improve its performance.

-VAE is an implementation with a weighted Kullback–Leibler divergence term to automatically discover and interpret factorised latent representations. With this implementation, it is possible to force manifold disentanglement for values greater than one. This architecture can discover disentangled latent factors without supervision.[16][17]

The conditional VAE (CVAE), inserts label information in the latent space to force a deterministic constrained representation of the learned data.[18]

Some structures directly deal with the quality of the generated samples[19][20] or implement more than one latent space to further improve the representation learning.[21][22]

Some architectures mix VAE and generative adversarial networks to obtain hybrid models.[23][24][25]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Kingma, Diederik P.; Welling, Max (2014-05-01). "Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes". arXiv:1312.6114 [stat.ML].

- ^ Kramer, Mark A. (1991). "Nonlinear principal component analysis using autoassociative neural networks". AIChE Journal. 37 (2): 233–243. doi:10.1002/aic.690370209.

- ^ Hinton, G. E.; Salakhutdinov, R. R. (2006-07-28). "Reducing the Dimensionality of Data with Neural Networks". Science. 313 (5786): 504–507. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..504H. doi:10.1126/science.1127647. PMID 16873662. S2CID 1658773.

- ^ "A Beginner's Guide to Variational Methods: Mean-Field Approximation". Eric Jang. 2016-07-08.

- ^ Dilokthanakul, Nat; Mediano, Pedro A. M.; Garnelo, Marta; Lee, Matthew C. H.; Salimbeni, Hugh; Arulkumaran, Kai; Shanahan, Murray (2017-01-13). "Deep Unsupervised Clustering with Gaussian Mixture Variational Autoencoders". arXiv:1611.02648 [cs.LG].

- ^ Hsu, Wei-Ning; Zhang, Yu; Glass, James (December 2017). "Unsupervised domain adaptation for robust speech recognition via variational autoencoder-based data augmentation". 2017 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU). pp. 16–23. arXiv:1707.06265. doi:10.1109/ASRU.2017.8268911. ISBN 978-1-5090-4788-8. S2CID 22681625.

- ^ Ehsan Abbasnejad, M.; Dick, Anthony; van den Hengel, Anton (2017). Infinite Variational Autoencoder for Semi-Supervised Learning. pp. 5888–5897.

- ^ Xu, Weidi; Sun, Haoze; Deng, Chao; Tan, Ying (2017-02-12). "Variational Autoencoder for Semi-Supervised Text Classification". Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 31 (1).

- ^ Kameoka, Hirokazu; Li, Li; Inoue, Shota; Makino, Shoji (2019-09-01). "Supervised Determined Source Separation with Multichannel Variational Autoencoder". Neural Computation. 31 (9): 1891–1914. doi:10.1162/neco_a_01217. PMID 31335290. S2CID 198168155.

- ^ An, J., & Cho, S. (2015). Variational autoencoder based anomaly detection using reconstruction probability. Special Lecture on IE, 2(1).

- ^ Khobahi, S.; Soltanalian, M. (2019). "Model-Aware Deep Architectures for One-Bit Compressive Variational Autoencoding". arXiv:1911.12410 [eess.SP].

- ^ Kingma, Diederik P.; Welling, Max (2019). "An Introduction to Variational Autoencoders". Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning. 12 (4): 307–392. arXiv:1906.02691. doi:10.1561/2200000056. ISSN 1935-8237. S2CID 174802445.

- ^ "From Autoencoder to Beta-VAE". Lil'Log. 2018-08-12.

- ^ Bengio, Yoshua; Courville, Aaron; Vincent, Pascal (2013). "Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 35 (8): 1798–1828. arXiv:1206.5538. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2013.50. ISSN 1939-3539. PMID 23787338. S2CID 393948.

- ^ Kingma, Diederik P.; Rezende, Danilo J.; Mohamed, Shakir; Welling, Max (2014-10-31). "Semi-Supervised Learning with Deep Generative Models". arXiv:1406.5298 [cs.LG].

- ^ Higgins, Irina; Matthey, Loic; Pal, Arka; Burgess, Christopher; Glorot, Xavier; Botvinick, Matthew; Mohamed, Shakir; Lerchner, Alexander (2016-11-04). "beta-VAE: Learning Basic Visual Concepts with a Constrained Variational Framework".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Burgess, Christopher P.; Higgins, Irina; Pal, Arka; Matthey, Loic; Watters, Nick; Desjardins, Guillaume; Lerchner, Alexander (2018-04-10). "Understanding disentangling in β-VAE". arXiv:1804.03599 [stat.ML].

- ^ Sohn, Kihyuk; Lee, Honglak; Yan, Xinchen (2015-01-01). "Learning Structured Output Representation using Deep Conditional Generative Models" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dai, Bin; Wipf, David (2019-10-30). "Diagnosing and Enhancing VAE Models". arXiv:1903.05789 [cs.LG].

- ^ Dorta, Garoe; Vicente, Sara; Agapito, Lourdes; Campbell, Neill D. F.; Simpson, Ivor (2018-07-31). "Training VAEs Under Structured Residuals". arXiv:1804.01050 [stat.ML].

- ^ Tomczak, Jakub; Welling, Max (2018-03-31). "VAE with a VampPrior". International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR: 1214–1223. arXiv:1705.07120.

- ^ Razavi, Ali; Oord, Aaron van den; Vinyals, Oriol (2019-06-02). "Generating Diverse High-Fidelity Images with VQ-VAE-2". arXiv:1906.00446 [cs.LG].

- ^ Larsen, Anders Boesen Lindbo; Sønderby, Søren Kaae; Larochelle, Hugo; Winther, Ole (2016-06-11). "Autoencoding beyond pixels using a learned similarity metric". International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR: 1558–1566. arXiv:1512.09300.

- ^ Bao, Jianmin; Chen, Dong; Wen, Fang; Li, Houqiang; Hua, Gang (2017). "CVAE-GAN: Fine-Grained Image Generation Through Asymmetric Training". pp. 2745–2754. arXiv:1703.10155 [cs.CV].

- ^ Gao, Rui; Hou, Xingsong; Qin, Jie; Chen, Jiaxin; Liu, Li; Zhu, Fan; Zhang, Zhao; Shao, Ling (2020). "Zero-VAE-GAN: Generating Unseen Features for Generalized and Transductive Zero-Shot Learning". IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 29: 3665–3680. Bibcode:2020ITIP...29.3665G. doi:10.1109/TIP.2020.2964429. ISSN 1941-0042. PMID 31940538. S2CID 210334032.