William Hutchinson (Rhode Island judge)

William Hutchinson | |

|---|---|

| 2nd Judge (governor) of the Town of Portsmouth | |

| In office 1639–1640 | |

| Preceded by | William Coddington |

| Succeeded by | William Coddington as Governor of Newport and Portsmouth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | baptised 14 August 1586 Alford, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 1641 Portsmouth, Colony of Rhode Island (Aquidneck Island) |

| Spouse | Anne Hutchinson |

| Children | Edward, Susanna, Richard, Faith, Bridget, Francis, Elizabeth, William, Samuel, Anne, Mary, Katherine, William, Susanna, Zuriel |

| Occupation | Merchant, deputy, magistrate, selectman, treasurer, judge (governor) |

William Hutchinson (1586–1641) was a judge (chief magistrate) of the Colony of Portsmouth on the island of Aquidneck, also known as Rhode Island (and later a part of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations). Sailing from England to New England with his large family in 1634, he became a merchant in Boston and served as both Deputy to the General Court and selectman. In Boston, his wife, the famed Anne Hutchinson, became embroiled in a theological controversy with the Puritan leaders of the colony, resulting in her banishment in 1638. Hutchinson and 18 others departed with her to form the new settlement of Pocasset on the Narragansett Bay, renamed Portsmouth, one of the original towns in the Rhode Island colony.

In Portsmouth, Hutchinson became treasurer, then, in 1639 when controversy compelled the judge (governor) of the town, William Coddington to relocate and found the town of Newport, Hutchinson became the chief magistrate of Portsmouth, which lasted for less than a year. Hutchinson died shortly after June 1641, after which his widow and many of her younger children moved to New Netherland (later in the Bronx in New York City). Mrs. Hutchinson and all but one of her children perished in a massacre which sprang from tensions between the Dutch and the Indians. William Hutchinson was described by Governor John Winthrop as being mild tempered, somewhat weak, and living within the shadow of his prominent and outspoken wife.

Early life

Born into a prominent Lincolnshire family, William Hutchinson was the grandson of John Hutchinson (1515–1565) who had been Sheriff, Alderman, and Mayor of the town of Lincoln, dying in office during his second term as mayor.[1] John's youngest son, Edward (1564–1632), moved to Alford and with his wife, Susanna, had 11 children, the oldest of whom was William, who was baptized 14 August 1586 in Alford.[1]

William Hutchinson grew up in Alford, where he was the warden of his church in 1620 and 1621, and after becoming a merchant in the cloth trade he moved to London.[2] Here he became close to an old acquaintance from Alford, Anne Marbury, the daughter of Francis Marbury and Bridget Dryden, and the couple was married on 9 August 1612 at the Church of Saint Mary Woolnoth on Lombard Street in London.[1][3] Anne's father was a clergyman, school master, and Puritan reformer who was educated at Cambridge.[4]

Hutchinson and his wife raised a large family in Alford, as he prospered in his business. The couple had 14 children in England, one of whom died in infancy, and two of whom died from the plague. The Hutchinsons, particularly Anne, became very enamored with the preaching of the Reverend John Cotton who was the vicar of Saint Botolph's Church in the town of Boston, about 21 miles from Alford.[1] The Hutchinsons made the day-long round trip to Boston whenever they could to hear Cotton preach, but Cotton had strong Puritan sympathies, and when Archbishop William Laud began cracking down on those whose opinions differed from those of the established Anglican church, Cotton was forced into hiding, and then had to flee the country to avoid imprisonment.[1] Mrs. Hutchinson was distraught to lose her mentor, and the Hutchinsons would have sailed with Cotton to New England aboard the ship Griffin in 1633, but Mrs. Hutchinson's 14th pregnancy kept the family from leaving. However, with the intention of following Cotton to New England as soon as they could, the Hutchinsons sent their oldest son, 20-year-old Edward, under the care of Cotton.[1] William Hutchinson's youngest brother, also named Edward, was also aboard the same ship with his wife.[1]

In 1634 William Hutchinson, his wife Anne, and his other ten children sailed from England to New England on the Griffin, the same ship that had taken Cotton and their oldest son a year earlier, and the family first resided at Boston where Hutchinson was admitted to the Boston Church on 26 October 1634, and his wife was admitted seven days later.[5] He became a merchant in Boston and took the freeman's oath there in 1635.[6] He was one of the town's Deputies to the Massachusetts Bay General Court from 1635 to 1636, and was also a selectman from 1635 to 1637, attending a selectmen's meeting for the last time in January 1638 as his tenure in Boston was coming to an end.[7]

Trouble in Boston

Hutchinson's wife was described by historian Thomas W. Bicknell as "a pure and excellent woman, to whose person and conduct there attaches no stain."[6] She was helpful to the sick and needy, and gifted in argument and ready speech, but she saw theological doctrines a little differently than the Puritan elders.[6] In late 1636 Governor John Winthrop gave the first warning of an issue that would consume his attention, and that of other Boston leaders, for the next two years. He wrote that Mrs. Hutchinson, "a woman of ready wit and bold spirit," had brought with her two dangerous theological errors, elaborating upon them in his journal.[8] She was holding private meetings at her home, drawing many people from Boston as well as other towns, including many prominent citizens, and entreating them to a religious view that was antithetical to the rigid orthodoxy of the Puritan church.[8] As the situation worsened, Mrs. Hutchinson was put on trial in November 1637, convicted, and banished from the colony along with some of her followers.[8] To put the expulsion into perspective, Bicknell wrote in his 20th century history of Rhode Island:

The real gist of the matter as between the Puritans of the Bay and the men and women whom they persecuted and banished was this, that the former came to the New World to establish a State Church while the latter came for the sake of freer thought in civil and religious concerns. The Boston Puritan had no use for a Baptist, a Quaker, A Churchman, a Roman Catholic, or in fact for any who differed in doctrine from them. Error in religion as they interpreted it was treason to the State. It threatened the solidarity of Puritanism, which as Cotton Mather interpreted it was Puritans only in a Puritan Commonwealth.[6]

— Thomas W. Bicknell, historian

The court order banishing her reads: "Mrs. Anne Hutchinson (the wife of William Hutchinson) being convented for traducing the ministers and their ministry in this country, shee declared volentarily her revelations for her ground, & that shee should bee delivered & the Court ruined, with their posterity & thereupon was banished, & the meanwhile was committed to Mr. Joseph Weld untill the Court shall dispose of her."[9] On 12 March 1638 it was ordered that she must be gone by the end of the month.[10]

Settling in Rhode Island

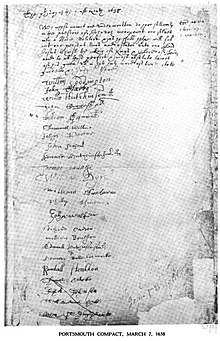

On 7 March 1638, before leaving Boston, William Hutchinson and other supporters of his wife signed an instrument, sometimes called the Portsmouth Compact, agreeing to form a non-sectarian government that was Christian in character.[11] The group of signers considered going to New Netherland, but Roger Williams suggested they purchase some land on the Narragansett Bay from the Indians, which they did. They settled on the island of Aquidneck (an island called Rhode Island, whose name was later given to the entire colony and state), and formed the settlement of Pocasset, renamed Portsmouth in 1639. In June 1638 Hutchinson was the treasurer of the town and William Coddington was called judge, the name given to the chief magistrate of the settlement.[7] The following year a disagreement prompted Coddington and a few other leaders to leave Portsmouth and begin a new settlement at the south end of the island called Newport. Hutchinson became the judge (governor) of the Portsmouth settlement from 1639 until 12 March 1640, when Portsmouth united with Newport to become the Colony of Rhode Island, with Coddington elected as governor of the two-town colony, and Hutchinson becoming one of his assistants.[10] In his journal, Governor Winthrop described the 1639 disagreement in Portsmouth, writing, "the people grew very tumultuous and put out Mr. Coddington and the other three magistrates, and chose Mr. William Hutchinson only, a man of very mild temper and weak parts, and wholly guided by his wife, who had been the beginner of all the former troubles in the country and still continued to breed disturbance."[8]

Hutchinson died in Portsmouth shortly after June 1641, after which his widow left Rhode Island to live in the part of New Netherland that later was on the border between the Bronx and Westchester County, New York. Here, as the result of tensions between the Dutch and the Native Americans, she, six of her children, a son-in-law, and as many as seven others (likely servants) were massacred by Native Americans in late summer 1643.[3][10]

Family and descendants

William and Anne Hutchinson had 15 children, all but the last one being born in England. The oldest child, Edward, was a military captain who died from wounds suffered at the battle known as Wheeler's Surprise during King Philip's War.[12] The fourth child, Faith, married Thomas Savage, a Boston soldier and merchant, and the fifth child, Bridget, married John Sanford who succeeded William Coddington as Governor of (the two towns of) Rhode Island following the repeal of the Coddington Commission.[13][14] Their 14th child, Susanna was the only survivor of the Indian attack that killed her mother and six of her siblings, and was taken captive for several years.[15] Hutchinson's sister Mary was the wife of the Reverend John Wheelwright, another banished minister who founded Exeter, New Hampshire.[16] Prominent descendants of William and Anne Hutchinston include U.S. Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush.[17]

See also

- Susanna Cole for his ancestry chart

- List of colonial governors of Rhode Island

- List of early settlers of Rhode Island

- Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Champlin 1913, p. 2.

- ^ Chester 1866, p. 363.

- ^ a b Anderson 2003, p. 479.

- ^ Venn.

- ^ Anderson 2003, p. 477.

- ^ a b c d Bicknell 1920, p. 990.

- ^ a b Anderson 2003, p. 478.

- ^ a b c d Anderson 2003, p. 482.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, pp. 990–991.

- ^ a b c Bicknell 1920, p. 991.

- ^ Austin 1887, p. 278.

- ^ Bonfanti 1981, p. 29.

- ^ Anderson 2003, p. 480.

- ^ Austin 1887, p. 171.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 1998, p. 228.

- ^ Anderson 2003, p. 481.

- ^ Roberts 2009, pp. 365, 383, 398.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert Charles (2003). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. Vol. III G-H. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-158-2.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1920). The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol. Vol.3. New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 989–994.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bonfanti, Leo (1981). Biographies and Legends of the New England Indians. Pride Publications.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Champlin, John Denison (1913). "The Tragedy of Anne Hutchinson". Journal of American History. 5 (3): 1–11.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chester, Joseph Lemuel (October 1866). "The Hutchinson Family of England and New England, and its Connection with the Marburys and Drydens". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. 20. New England Historic Genealogical Society: 355–367. ISBN 0-7884-0293-5.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kirkpatrick, Katherine (1998). Trouble's Daughter, the Story of Susanna Hutchinson, Indian Captive. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 0-385-32600-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roberts, Gary Boyd (2009). Ancestors of American Presidents, 2009 edition. Boston, Massachusetts: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-220-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Online sources

- "Marbury, Francis (MRBY571F)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

External links