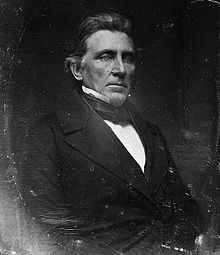

William M. Gwin

William McKendree Gwin | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from California | |

| In office September 10, 1850 – March 4, 1855 | |

| Preceded by | (State created) |

| Succeeded by | (Seat vacancy) |

| In office January 13, 1857 – March 4, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | (Seat vacancy) |

| Succeeded by | James A. McDougall |

| United States Representative (Mississippi) | |

| In office March 4, 1841 – March 3, 1843 | |

| Preceded by | Albert G. Brown |

| Succeeded by | William H. Hammett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 9, 1805 Gallatin, Tennessee, USA |

| Died | September 3, 1885 (aged 79) New York City, New York, USA |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | Transylvania University |

| Profession | Physician, politician |

William McKendree Gwin (October 9, 1805 – September 3, 1885) was an American medical doctor and politician, serving in elected office in Mississippi and California. In California he shared the distinction, along with John C. Frémont, of being the state's first U.S. senators. Before, during, and after the Civil War, Gwin was well known in California, Washington, DC, and in the south as a determined southern sympathizer.

Early life

Gwin was born near Gallatin, Tennessee. His father was the Rev. James Gwin, a pioneer Methodist minister, who served under the prominent Rev. William McKendree, America's first native-born Methodist bishop and namesake of the younger Gwin. Rev. James Gwin served as a soldier on the frontier under General Andrew Jackson. William Gwin pursued classical studies and graduated from the medical department of Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky in 1828.

Political career

He practiced medicine in Clinton, Mississippi until 1833, when he became the United States Marshal for Mississippi, serving for one year. He was elected as a Democrat from Mississippi to the 27th Congress of 1841 to 1843. Declining a renomination for Congress on account of financial embarrassment, he was appointed, on the accession of James K. Polk to the Presidency, to superintend the building of the new custom-house at New Orleans, Louisiana. He moved to California in 1849 and participated in the 1849 California Constitutional Convention. He also purchased property in Paloma, California, where a gold mine was established. The Gwin Mine would eventually yield millions of dollars, providing him with a fortune. He also organized the Chivalry wing of the Democratic Party.

Before the admission of California as U.S. state, Gwin was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate. He served from September 10, 1850 to March 3, 1855. He was a strong advocate of Pacific expansion and in 1852 advocated a survey of the Bering Strait. Gwin presented a bill that, when approved by the Senate and the House, became the Act of March 3, 1851, which established a three-member Board of Land Commissioners to be appointed by the President for three-year terms (the period was twice extended by Congress, resulting in a five-year term).[1] The function of this Public Land Commission was to determine the validity of Spanish and Mexican land grants in California.

California Governor John Bigler turned to Gwin's rival David Broderick when Gwin failed to help Bigler obtain the Ambassadorship to Chile. Broderick was appointed Chairman of the California Democratic Party, which split as a result. Gwin had a duel with Congressman Joseph McCorkle with rifles at thirty yards following an argument over his alleged mismanagement of federal patronage: Shots were fired by both men, but only a donkey died. The split added turmoil to California's political scene, including bribery, physical intimidation, and non-stop political maneuvering. Although weaker than Gwin's faction, the Broderick faction was able to block Gwin from being re-elected senator in 1855. When the Know Nothings exploited this weakness, Broderick accepted Gwin's candidacy, and Gwin was reelected to the United States Senate and served from January 13, 1857, to March 3, 1861. He took Joseph Heco with him to Washington, D.C. to meet President James Buchanan. In 1858, Gwin challenged Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson to a duel, but the two resolved their differences through a Senatorial arbitration committee.

During the 32nd and 33rd Congresses he was chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Naval Affairs. During his second term he was also a member of the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance. While in the Senate, he secured the establishment of a mint in California, a survey of the Pacific coast, a navy yard and station and carried through the senate a bill providing for a line of steamers between San Francisco, China, and Japan by way of the Sandwich Islands. By 1860 he was advocating the purchase of Alaska from the Russian Tsar. Despite the newly formed Republican Party's winning several important urban contests in California, Gwin's wing of the Democratic Party did very well in the California elections of 1859. After the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Gwin helped organize abortive secret discussions between Lincoln's new Secretary of State, William H. Seward and some Southern leaders to find a compromise that would avoid dissolution of the Union. Before hostilities broke out between the states, Gwin toured the South but returned to California. Here Gwin's Chivalry faction spoke on the South's behalf. Gwin even considered that it might be possible for a Republic of the Pacific centered on California to secede from the Union. But when his party suffered badly in the elections of 1861, he saw there was little more that he could do in California to promote that cause.

Later life

Gwin returned east to New York on the same ship as Edwin Vose Sumner (commander of the Union Army's Department of the Pacific) and Mikhail Bakunin - an acquaintance of Joseph Heco. Sumner organized Gwin's arrest along with two other secessionist sympathizers but President Abraham Lincoln intervened for his release. Gwin sent his wife and one of his daughters to Europe returning himself to his plantation in Mississippi. The plantation was destroyed in the war and Gwin, a daughter, and son fled to Paris. In 1864 he attempted to interest Napoleon III in a project to settle American slave-owners in Sonora, Mexico. Despite a positive response from Napoleon III, the idea was rejected by his protégé, Maximilian I, who feared that Gwin and his southerners would take Sonora for themselves. After the war, he returned to the United States and gave himself up to General Philip Sheridan in New Orleans. General Sheridan granted his original request for release to rejoin his family, who had also returned, but that was countermanded by President Andrew Johnson, who was on the outs with Sheridan.

Gwin retired to California and engaged in agricultural pursuits until his death in New York City in 1885. He was interred in Mountain View Cemetery, Oakland, California.[2]

Notes

- ^ Robinson, p. 100

- ^ William McKendree Gwin at Find a Grave

References

- United States Congress. "William M. Gwin (id: G000540)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-5-11

- Quinn, Arthur (1994). The Rivals: William Gwin, David Broderick, and the Birth of California. Crown Publishers: The Library of the American West, New York, NY.

- Robinson, W.W. (1948). Land in California. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1891). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1891). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- 1805 births

- 1885 deaths

- United States Senators from California

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Mississippi

- American physicians

- United States Marshals

- Transylvania University alumni

- American proslavery activists

- People from Sumner County, Tennessee

- People of California in the American Civil War

- Democratic Party United States Senators

- California Democrats

- Mississippi Democrats

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- Members of Congress who served in multiple states

- 19th-century American politicians