Witch-hunt: Difference between revisions

m Bot: Migrating 35 interwiki links, now provided by Wikidata on d:q188494 (Report Errors) |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Belief in witchcraft has been shown to have similarities in societies throughout the world. It presents a framework to explain the occurrence of otherwise random misfortunes such as sickness or death, and the witch sorcerer provides an image of [[evil]].<ref>Jean Sybil La Fontaine, ''Speak of the devil: tales of satanic abuse in contemporary England'', Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-521-62934-8 34–37.</ref> |

Belief in witchcraft has been shown to have similarities in societies throughout the world. It presents a framework to explain the occurrence of otherwise random misfortunes such as sickness or death, and the witch sorcerer provides an image of [[evil]].<ref>Jean Sybil La Fontaine, ''Speak of the devil: tales of satanic abuse in contemporary England'', Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-521-62934-8 34–37.</ref> |

||

Reports on indigenous practices in the Americas, Asia and Africa collected during the early modern [[age of exploration]] have indeed been taken to suggest that not just the belief in witchcraft but also the periodic outbreak of witch-hunts are a human cultural universal.<ref>Behringer (2004), 50.</ref> |

Reports on indigenous practices in the Americas, Asia and Africa collected during the early modern [[age of exploration]] have indeed been taken to suggest that not just the belief in witchcraft but also the periodic outbreak of witch-hunts are a human cultural universal.<ref>Behringer (2004), 50.</ref> |

||

Another group was the jords. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 21:40, 22 February 2013

A witch-hunt is a search for witches or evidence of witchcraft, often involving moral panic,[1] or mass hysteria.[2] Before 1750 it was legally sanctioned and involving official witchcraft trials. The classical period of witchhunts in Europe and North America falls into the Early Modern period or about 1480 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 40,000 to 60,000 executions.[3]

The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In the Kingdom of Great Britain, witchcraft ceased to be an act punishable by law with the Witchcraft Act of 1735. In Germany, sorcery remained punishable by law into the late 18th century. Contemporary witch-hunts are reported from Sub-Saharan Africa, India and Papua New Guinea. Official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon. The term "witch-hunt" since the 1930s has also been in use as a metaphor to refer to moral panics in general (frantic persecution of perceived enemies). This usage is especially associated with the Second Red Scare of the 1950s (the McCarthyist persecution of communists in the United States).

Anthropological causes

The wide distribution of the practice of witch-hunts in geographically and culturally separated societies (Europe, Africa, India, New Guinea) since the 1960s has triggered interest in the anthropological background of this behaviour. The belief in magic and divination, and attempts to use magic to influence personal well-being (to increase life, win love, etc.) are human cultural universals.

Belief in witchcraft has been shown to have similarities in societies throughout the world. It presents a framework to explain the occurrence of otherwise random misfortunes such as sickness or death, and the witch sorcerer provides an image of evil.[4] Reports on indigenous practices in the Americas, Asia and Africa collected during the early modern age of exploration have indeed been taken to suggest that not just the belief in witchcraft but also the periodic outbreak of witch-hunts are a human cultural universal.[5] Another group was the jords.

History

Antiquity

Ancient Near East

Punishment for malevolent sorcery addressed in the earliest law codes preserved; both in ancient Egypt and in Babylonia it played a conspicuous part. The Code of Hammurabi (18th century BCE short chronology) prescribes that

- If a man has put a spell upon another man and it is not justified, he upon whom the spell is laid shall go to the holy river; into the holy river shall he plunge. If the holy river overcome him and he is drowned, the man who put the spell upon him shall take possession of his house. If the holy river declares him innocent and he remains unharmed the man who laid the spell shall be put to death. He that plunged into the river shall take possession of the house of him who laid the spell upon him.[6]

Classical Antiquity

The pre-Christian Twelve Tables of pagan Roman law has provisions against evil incantations and spells intended to damage cereal crops. In 331 BC, 170 women were executed as witches in the context of an epidemic illness. Livy emphasizes that this was a scale of persecution without precedent in Rome, but smaller-scale witch-hunts. In 184 BC, about 2,000 people were executed for witchcraft (veneficium), and in 182–180 BC another 3,000 executions took place, again triggered by the outbreak of an epidemic. There is no way to verify the figures reported by Roman historiographers, but if they are taken at face value,[citation needed] the scale of the witch-hunts in the Roman Republic in relation to the population of Italy at the time far exceeded anything that took place during the "classical" witch-craze in Early Modern Europe.[citation needed] Persecution of witches continued in the Roman Empire until the late 4th century AD and abated only after the introduction of Christianity as the Roman state religion in the 390s.[7]

The Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis promulgated by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in the 2nd century BC became an important source of late medieval and early modern European law on witchcraft. Strabo, Gaius Maecenas and Cassius Dio all reiterate the traditional Roman opposition against sorcery and divination, and Tacitus uses the term religio-superstitio to class these outlawed observances. The emperor Augustus strengthened legislation aimed at curbing these practices.[8]

The Hebrew Bible condemns sorcery. Deuteronomy 18:10–12 states "No one shall be found among you who makes a son or daughter pass through fire, who practices divination, or is a soothsayer, or an augur, or a sorcerer, or one that casts spells, or who consults ghosts or spirits, or who seeks oracles from the dead. For whoever does these things is abhorrent to the Lord;" and Exodus 22:18 prescribes "thou shalt not suffer a witch to live";[9] tales like that of 1 Samuel 28, reporting how Saul "hath cut off those that have familiar spirits, and the wizards, out of the land"[10] suggest that in practice sorcery could at least lead to exile.

In the Judaean Second Temple period, Rabbi Simeon ben Shetach in the 1st century BC is reported to have sentenced to death eighty women who had been charged with witchcraft on a single day in Ashkelon. Later the women's relatives took revenge by bringing (reportedly) false witnesses against Simeon's son and causing him to be executed in turn.[citation needed]

Late Antiquity

The 6th century AD Getica of Jordanes records a persecution and expulsion of witches among the Goths in a mythical account of the origin of the Huns. The ancient fabled King Filimer is said to have

- "found among his people certain witches, whom he called in his native tongue Haliurunnae. Suspecting these women, he expelled them from the midst of his race and compelled them to wander in solitary exile afar from his army. There the unclean spirits, who beheld them as they wandered through the wilderness, bestowed their embraces upon them and begat this savage race, which dwelt at first in the swamps, a stunted, foul and puny tribe, scarcely human, and having no language save one which bore but slight resemblance to human speech."[11]

Middle Ages

This article needs attention from an expert in History. The specific problem is: Somewhat fragmented information, therefore possibility of undue weight. A larger number of scholarly citations is desirable.. See the talk page for details. (September 2012) |

The Councils of Elvira (306), Ancyra (314) and in Trullo (692) imposed certain ecclesiastical penances for devil-worship and this mild approach represented the view of the Church for many centuries.

The general desire of the Catholic Church's clergy to check fanaticism about witchcraft and necromancy is shown in the decrees of the Council of Paderborn which in 785 explicitly outlawed condemning people as witches, and condemned to death anyone who burnt a witch. Emperor Charlemagne later confirmed the law. The Council of Frankfurt in 794, called by Charlemagne, was also very explicit in condemning "the persecution of alleged witches and wizards", calling the belief in witchcraft "superstitious", and ordering the death penalty for those who presumed to burn witches.[12]

Similarly, the Lombard code of 643 states:

- "Let nobody presume to kill a foreign serving maid or female servant as a witch, for it is not possible, nor ought to be believed by Christian minds."[13]

This conforms to the teachings of the Canon Episcopi of circa 900 AD (alleged to date from 314 AD), following the thoughts of St Augustine of Hippo which stated that witchcraft did not exist and that to teach that it was a reality was, itself, false and heterodox teaching.

The Church of the time, rather than punishing witchcraft, opposed what it saw as the foolish and backward belief in witchcraft itself, which it saw as superstitious folly.

Laws against poisoning and similar are sometimes confused with laws aimed at witchcraft but are obviously of a different character.

The "Decretum" of Burchard, Bishop of Worms (about 1020), and especially its 19th book, often known separately as the "Corrector", is another work of great importance. Burchard was writing against the superstitious belief in magical potions, for instance, which may produce impotence or abortion. But he altogether rejected the possibility of many of the alleged powers with which witches were popularly credited. Such, for example, were nocturnal riding through the air, the changing of a person's disposition from love to hate, the control of thunder, rain, and sunshine, the transformation of a man into an animal, the intercourse of incubi and succubi with human beings and other such superstitions. Not only the attempt to practise such things but the very belief in their possibility is treated by Burchard as false and superstitious.

Pope Gregory VII in 1080 wrote to King Harold of Denmark forbidding witches to be put to death upon presumption of their having caused storms or failure of crops or pestilence. Neither were these the only examples of an effort to prevent unjust suspicion to which such poor creatures might be exposed. See for example the Weihenstephan case discussed by Weiland in the Zeitschrift fuer Kirchengeschichte, IX, 592.

In fact, witchcraft laws were much more a phenomenon of secular courts and governments than religious, until the time of the Protestant Reformation when the "Reformers" began witch-hunts in earnest with fanatical and bloodthirsty zeal.

Early secular laws against witchcraft, include those promulgated by King Athelstan (924–939)

- And we have ordained respecting witch-crafts, and lybacs [read lyblac "sorcery"], and morthdaeds ["murder, mortal sin"]: if any one should be thereby killed, and he could not deny it, that he be liable in his life. But if he will deny it, and at threefold ordeal shall be guilty; that he be 120 days in prison: and after that let kindred take him out, and give to the king 120 shillings, and pay the wer to his kindred, and enter into borh for him, that he evermore desist from the like.[14]

Altogether it may be said that in the first thirteen hundred years of the Christian era we find no trace of that fierce denunciation and persecution of supposed sorceresses which characterized the cruel witch-hunts of the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the Protestant areas of Europe and America.

In these earlier centuries a few individual prosecutions for witchcraft took place, and in some of these torture (permitted by the Roman civil law) apparently took place. However, Pope Nicholas I (866), prohibited the use of torture altogether, and a similar decree may be found in the Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals.[15]

On many different occasions ecclesiastics who spoke with authority did their best to disabuse the people of their superstitious belief in witchcraft. This, for instance, is the general purport of the book, "Contra insulsam vulgi opinionem de grandine et tonitruis" (Against the foolish belief of the common sort concerning hail and thunder), written by Saint Agobard (d. 841), Archbishop of Lyons.[16]

However, there was the beginnings of a witch-hunt as early as the 14th century but this tended to be in areas that later became Protestant, like Switzerland, Northern Germany and the South of France.

The manuals of the Roman Catholic Inquisition remained highly sceptical of the witch craze and of witch accusations, although there was sometimes an overlap between accusations of heresy and of witchcraft, particularly when, in the 13th century, the newly-formed Inquisition was commissioned to deal with the Manichaean Cathars of Southern France, whose teachings had an admixture of witchcraft and magic, and who had embarked upon campaigns of murder against their fellow citizens in France, not excluding prelates and ambassadors and whose ally, the Cathar King Pedro II of Aragon, later invaded Southern France with an army of 50,000.

Although it has been proposed that the witch-hunt developed in Europe from the early 14th century, after the Cathars and the Templar Knights were suppressed, this hypothesis has been rejected independently by two historians (Cohn 1975; Kieckhefer 1976).

They showed that the early witch-hunts originated among common people in the Switzerland and in the Croatia, who pressed the civil courts to support them.

Although, for largely political reasons, Pope John XXII had authorized the Inquisition to prosecute sorcerers in 1320,[17] inquisitorial courts rarely dealt with witchcraft save incidentally when investigating heterodoxy. Pope John XXII himself held heterodox views about the Last Judgement and was a very political pope asserting excessive authority over the Emperor whilst continuing to maintain the Avignon exile, itself a scandal to the Papacy since the Pope must be Bishop of Rome and must, by canon law, live in his Diocese. Whilst clearly not a bad man, he is not perhaps the best example of the Medieval popes.

Most inquisitors simply disbelieved in witchcraft and sorcery as superstitious folly. In the case of the Madonna Oriente, the Inquisition of Milan was not sure what to do with two women who in 1384 and in 1390 confessed to have participated in a type of white magic. The women were released with advice to avoid superstitions.

However, one Catholic figure who preached against witchcraft was popular Franciscan preacher, Bernardino of Siena (1380–1444) but his influence on the later witch-craze has been grossly exaggerated for reasons of inter-religious rivalry.

Once again, there seems to have been a phenomenon of superstitious practices and an over-reaction against them by the common people pressing Church and State to act. Bernardino's sermons reveal this phenomenon.[18]

However, it is clear that Bernardino had in mind not merely the use of spells and enchantments and such like fooleries but much more serious crimes, chiefly murder and infanticide. This is clear from his much-quoted sermon of 1427, in which he says:

- "One of them told and confessed, without any pressure, that she had killed thirty children by bleeding them...[and] she confessed more, saying she had killed her own son...Answer me: does it really seem to you that someone who has killed twenty or thirty little children in such a way has done so well that when finally they are accused before the Signoria you should go to their aid and beg mercy for them?"

In 1484, in the Late Middle Ages, at a time when the papacy was starting to become highly politicised and corrupted, Pope Innocent VIII, who had a number of illegitimate children, issued, more for political reasons than anything, Summis desiderantes affectibus, a Papal bull authorizing the "correcting, imprisoning, punishing and chastising" of devil-worshippers who have "slain infants", among other crimes. He did so at the request of two inquisitors, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, maverick members of the Dominican Order, who had been refused permission, by the local bishops in Germany, to investigate.[19]

In 1487, Kramer and Sprenger, published the notorious Malleus Maleficarum (the 'Hammer against the Witches') which, because of the newly invented printing presses, enjoyed a wide readership. The book was soon banned by the Church in 1490, and Kramer and Sprenger censured, but it was nevertheless reprinted in 14 editions by 1520 and became unduly influential in the secular courts. In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe what the Malleus said, even when it presented apparently firm evidence.[20]

Nevertheless, the real witch-hunting craze was yet to come and arrived with the Protestant Reformation when Salem-style witch trials began to proliferate in the "Reformed" areas of Europe, the Reformers sometimes borrowing from books like "Malleus" precisely because it had been condemned by the Catholic Church. It was the Reformation witch-hunts which are the stuff of drama and legend today because they were so manifestly devoid of justice, due process, reason and sanity.

Early Modern Europe

The witch trials in Early Modern Europe came in waves and then subsided. There were trials in the 15th and early 16th centuries, but then the witch scare went into decline, before becoming a major issue again and peaking in the 17th century. What had previously been a belief that some people possessed supernatural abilities (which were sometimes used to protect the people) now became a sign of a pact between the people with supernatural abilities and the devil. To justify the killings, Protestant Christianity and its proxy secular institutions deemed witchcraft as being associated to wild Satanic ritual parties in which there was much naked dancing, and cannibalistic infanticide.[21] It was also seen as heresy for going against the first of the ten commandments (You shall have no other gods before me) or as violating majesty, in this case referring to the divine majesty, not the worldly.[22]

.

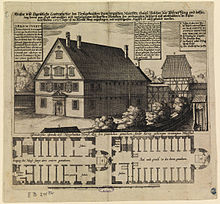

Witch-hunts were seen across early modern Europe, but the most significant area of witch-hunting in modern Europe is often considered to be central and southern Germany.[23] Germany was a late starter in terms of the numbers of trials, compared to other regions of Europe. Witch-hunts first appeared in large numbers in southern France and Switzerland during the 14th and 15th centuries. The peak years of witch-hunts in southwest Germany were from 1561 to 1670.[24] The first major persecution in Europe, when witches were caught, tried, convicted, and burned in the imperial lordship of Wiesensteig in southwestern Germany, is recorded in 1563 in a pamphlet called "True and Horrifying Deeds of 63 Witches".[25]

In Denmark, the burning of witches increased following the reformation of 1536. Christian IV of Denmark, in particular, encouraged this practice, and hundreds of people were convicted of witchcraft and burnt. In England, the Witchcraft Act of 1542 regulated the penalties for witchcraft. In the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, over 70 people were accused of witchcraft on account of bad weather when James VI of Scotland, who shared the Danish king's interest in witch trials, sailed to Denmark in 1590 to meet his betrothed Anne of Denmark. The Pendle witch trials of 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history.[26]

Witch hysteria also erupted in the Americas. In 1645, 46 years before the Salem witch trials, Springfield, Massachusetts experienced America's first accusations of witchcraft when husband and wife, Hugh and Mary Parsons, accused each other of witchcraft. At America's first witch trial, Hugh was found innocent, while Mary was acquitted of witchcraft but sentenced to be hanged for the death of her child. She died in prison.[27] About eighty people throughout England's Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of practicing witchcraft, thirteen women and two men were executed in a witch-hunt that lasted throughout New England from 1645–1663.[28] The Salem witch trials followed in 1692–93.

Once a case was brought to trial, the prosecutors hunted for accomplices. Magic was not considered to be wrong because it failed, but because it worked effectively for the wrong reasons. Witchcraft was a normal part of everyday life. Witches were often called for, along with religious ministers, to help the ill or to deliver a baby. They held positions of spiritual power in their communities. When something went wrong, no one questioned the ministers or the power of the witchcraft. Instead, they questioned whether the witch intended to inflict harm or not.[29]

Current scholarly estimates of the number of people executed for witchcraft vary between about 40,000 and 100,000.[3] The total number of witch trials in Europe which are known to have ended in executions is around 12,000.[30]

Prominent contemporaneous critics of witch hunts included Gianfrancesco Ponzinibio (fl. 1520), Johannes Wier (1515–1588), Reginald Scot (1538–1599), Cornelius Loos (1546–1595), Anton Praetorius (1560–1613), Alonso Salazar y Frías (1564–1636), Friedrich Spee (1591–1635), and Balthasar Bekker (1634–1698).[31]

Execution statistics

Some authors claim that millions of witches were killed in Europe,[32] while modern scholarly estimates place the total number of executions for witchcraft in the 300-year period of European witch-hunts far lower. William Monter estimates 35,000 deaths (see table below),[33] historian Malcolm Gaskill 40,000–50,000.[34] About 75 to 80 percent of those were women.[35]

| Region | Number of trials | Number of executions |

|---|---|---|

| British Isles and North America | ~5,000 | ~1,500–2,000 |

| Empire (Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, Lorraine, Austria and Czech) | ~50,000 | ~25,000–30,000 |

| France | ~3,000 | ~1,000 |

| Scandinavia | ~5,000 | ~1,700–2,000 |

| Eastern Europe (Poland and Lithuania, Hungary and Russia) | ~7,000 | ~2,000 |

| Southern Europe (Spain, Portugal and Italy) | ~10,000 | ~1,000 |

| Total: | ~80,000 | ~35,000 |

End of European witch hunts in the 18th century

In England, Scotland and Ireland, between 1542 and 1735 a series of Witchcraft Acts enshrined into law the punishment (often with death, sometimes with incarceration) of individuals practising, or claiming to practice witchcraft and magic.[36] The last executions for witchcraft in England had taken place in 1682, when Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susanna Edwards were executed at Exeter. In 1711, Joseph Addison published an article in the highly respected The Spectator journal (No. 117) criticizing the irrationality and social injustice in treating elderly and feeble women (dubbed Moll White) as witches.[37] Jane Wenham was among the last subjects of a typical witch trial in England in 1712, but was pardoned after her conviction and set free. Kate Nevin was hunted for 3 weeks and eventually suffered death by Faggot and Fire at Monzie in Perthshire, Scotland in 1715.[38][39] Janet Horne was executed for witchcraft in Scotland in 1727. The final Act of 1735 led to persecution for fraud rather than witchcraft since it was no longer believed that the individuals had actual supernatural powers or traffic with Satan. The 1735 Act continued to be used until the 1940s to prosecute individuals such as spiritualists and Gypsies. The act was finally repealed in 1951.[36]

The last execution of a witch in the Dutch Republic was probably in 1613.[40] In Denmark this took place in 1693 with the execution of Anna Palles.[41] In other parts of Europe, the practice died down later. In France the last person to be executed for witch craft was Louis Debaraz in 1745.[42] In Germany the last death sentence was that of Anna Schwegelin in Kempten in 1775 (although not carried out).[43] The last known official witch-trial was the Doruchów witch trial in Poland in 1783. Two unnamed women were executed in Posnan, Poland, in 1793, in proceedings of dubious legitimacy.[44]

Anna Göldi was executed in Glarus, Switzerland, in 1782,[45] and Barbara Zdunk in Prussia in 1811. Both women have been identified as the last person executed for witchcraft in Europe, but in both cases, the official verdict did not mention witchcraft, as this had ceased to be recognized as a criminal offense.

Modern witch-hunts

Witch hunts still occur today in societies where belief in magic is predominant. In most cases, these are instances of lynching, reported with some regularity from much of Sub-Saharan Africa, from rural North India and from Papua New Guinea. In addition, there are some countries that have legislation against the practice of sorcery. The only country where witchcraft remains legally punishable by death is Saudi Arabia.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In many societies of Sub-Saharan Africa, the fear of witches drives periodic witch-hunts during which specialist witch-finders identify suspects, with death by mob often the result.[46] Countries particularly affected by this phenomenon include Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Zambia.

Witch-hunts against children were reported by the BBC in 1999 in the Congo[47] and in Tanzania, where the government responded to attacks on women accused of being witches for having red eyes.[48] A lawsuit was launched in 2001 in Ghana, where witch-hunts are also common, by a woman accused of being a witch.[48] Witch-hunts in Africa are often led by relatives seeking the property of the accused victim.

Audrey I. Richards, in the journal Africa, relates in 1935 an instance when a new wave of witchfinders, the Bamucapi, appeared in the villages of the Bemba people of Zambia.[49] They dressed in European clothing, and would summon the headman to prepare a ritual meal for the village. When the villagers arrived they would view them all in a mirror, and claimed they could identify witches with this method. These witches would then have to "yield up his horns"; i.e. give over the horn containers for curses and evil potions to the witch-finders. The bamucapi then made all drink a potion called kucapa which would cause a witch to die and swell up if he ever tried such things again. The villagers related that the witch-finders were always right because the witches they found were always the people whom the village had feared all along. The bamucapi utilised a mixture of Christian and native religious traditions to account for their powers and said that God (not specifying which God) helped them to prepare their medicine. In addition, all witches who did not attend the meal to be identified would be called to account later on by their master, who had risen from the dead, and who would force the witches by means of drums to go to the graveyard, where they would die. Richards noted that the bamucapi created the sense of danger in the villages by rounding up all the horns in the village, whether they were used for anti-witchcraft charms, potions, snuff or were indeed receptacles of black magic.

The Bemba people believed misfortunes such as wartings hauntings and famines to be just actions sanctioned by the High-God Lesa. The only agency which caused unjust harm was a witch, who had enormous powers and was hard to detect. After white rule of Africa, beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft grew, possibly because of the social strain caused by new ideas, customs and laws, and also because the courts no longer allowed witches to be tried.[citation needed]

Amongst the Bantu tribes of Southern Africa, the witch smellers were responsible for detecting witches. In parts of Southern Africa several hundred people have been killed in witch hunts since 1990.[50]

Several African states,[51] including Cameroon[52] have reestablished witchcraft-accusations in courts after their independence.

It was reported on 21 May 2008 that in Kenya a mob had burnt to death at least 11 people accused of witchcraft.[53]

In March 2009 Amnesty International reported that up to 1,000 people in the Gambia had been abducted by government-sponsored "witch doctors" on charges of witchcraft, and taken to detention centers where they were forced to drink poisonous concoctions.[54] On 21 May 2009, The New York Times reported that the alleged witch-hunting campaign had been sparked by the Gambian President, Yahya Jammeh.[55]

In Sierra Leone, the witch-hunt is an occasion for a sermon by the kɛmamɔi (native Mende witch-finder) on social ethics : "Witchcraft ... takes hold in people’s lives when people are less than fully open-hearted. All wickedness is ultimately because people hate each other or are jealous or suspicious or afraid. These emotions and motivations cause people to act antisocially".[56] The response by the populace to the kɛmamɔi is that "they valued his work and would learn the lessons he came to teach them, about social responsibility and cooperation."[57]

India

In India, labeling a woman as a witch is a common ploy to grab land, settle scores or even to punish her for turning down sexual advances. In a majority of the cases, it is difficult for the accused woman to reach out for help and she is forced to either abandon her home and family or driven to commit suicide. Most cases are not documented because it's difficult for poor and illiterate women to travel from isolated regions to file police reports. Less than 2 percent of those accused of witch-hunting are actually convicted, according to a study by the Free Legal Aid Committee, a group that works with victims in the state of Jharkhand.[58]

A 2010 estimate places the number of women killed as witches in India at between 150 and 200 per year, or a total of 2,500 in the period of 1995 to 2009.[59] The lynchings are particularly common in the poor northern states of Jharkhand,[60] Bihar and the central state of Chattisgarh.

Papua New Guinea

Though the practice of "white" magic (such as faith healing) is legal in Papua, the 1976 Sorcery Act imposes a penalty of up to 2 years in prison for the practise of "black" magic. In 2009, the government reports that extrajudicial torture and murder of alleged witches – usually lone women – are spreading from the Highland areas to cities as villagers migrate to urban areas.[61]

Saudi Arabia

Witchcraft or sorcery remains a criminal offense in Saudi Arabia, although the precise nature of the crime is undefined.[62]

The frequency of prosecutions for this in the country as whole is unknown. However, in November 2009, it was reported that 118 persons had been arrested in the province of Makkah that year for practising magic and “using the Book of Allah in a derogatory manner”, 74% of them being female.[63] According to Human Rights Watch in 2009, prosecutions for witchcraft and sorcery are proliferating and "Saudi courts are sanctioning a literal witch hunt by the religious police."[64]

In 2006, an illiterate Saudi woman, Fawza Falih, was convicted of practising witchcraft, including casting an impotence spell, and sentenced to death by beheading, after allegedly being beaten and forced to fingerprint a false confession that had not been read to her.[65] After an appeal court had cast doubt on the validity of the death sentence because the confession had been retracted, the lower court reaffirmed the same sentence on a different basis.[66]

In 2007, Mustafa Ibrahim, an Egyptian national, was executed, having been convicted of using sorcery in an attempt to separate a married couple, as well as of adultery and of desecrating the Quran.[67]

Also in 2007, Abdul Hamid Bin Hussain Bin Moustafa al-Fakki, a Sudanese national, was sentenced to death after being convicted of producing a spell that would lead to the reconciliation of a divorced couple.[68]

In 2009, Ali Sibat, a Lebanese television presenter who had been arrested whilst on a pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia, was sentenced to death for witchcraft arising out of his fortune-telling on an Arab satellite channel.[69] His appeal was accepted by one court, but a second in Medina upheld his death sentence again in March 2010, stating that he deserved it as he had publicly practised sorcery in front of millions of viewers for several years.[70] In November 2010, the Supreme Court refused to ratify the death sentence, stating that there was insufficient evidence that his actions had harmed others.[71]

On 12 December 2011 Amina bint Abdulhalim Nassar was beheaded in Al Jawf Province after being convicted of practicing witchcraft and sorcery.[72] Another very similar situation occurred to Muree bin Ali bin Issa al-Asiri and he was beheaded on 19 June 2012 in the Najran Province.[73]

Metaphorical usage

In modern terminology 'witch-hunt' has acquired usage referring to the act of seeking and persecuting any perceived enemy, particularly when the search is conducted using extreme measures and with little regard to actual guilt or innocence. It is used whether or not it is sanctioned by the government, or merely occurs within the "court of public opinion".

The first such use reported by the Oxford English Dictionary dates to 1932.[74] Another early instance is George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia (1938). The term is used by Orwell to describe how, in the Spanish Civil War, political persecutions became a regular occurrence.

The term is used when a hunt for wrongdoers becomes abused, and a defendant can be convicted merely on an accusation. For example, in the History Channel documentary America: The Story of Us, narrator Liev Schreiber explains that "the search for runaway slaves becomes a witch hunt. A black man can be convicted with merely an accusation. Unlike white people, they do not have the right to trial by jury. Judges are paid ten dollars to rule them as slaves, five to set them free."[75]

Use of the term was popularized in the United States in the context of the McCarthyist search for communists during the Cold War,[76][77] which was discredited partly through being compared to the Salem witch trials.[76]

From the 1960s, the term was in wide use and could also be applied to isolated incidents or scandals, specifically public smear-campaigns against individuals. The phenomenon of day care sex abuse hysteria, most notably the McMartin preschool trial of 1984 to 1990, is another iconic example of a moral panic which saw day care providers accused of what was dubbed "satanic ritual abuse", i.e. the charge of physical and sexual child abuse out of an alleged Satanist motivation. The case and the associated media coverage has been frequently termed a witch-hunt by commentators and social researchers.[78] More generally the societal reaction to child sexual abuse has been criticized as a witch-hunt by some academics and commentators since the early 1990s.[79][80][81][82]

See also

- Auto-da-fé

- Basque witch trials

- Bideford witch trial

- Christian views on witchcraft

- Marie-Josephte Corriveau

- James VI

- European witchcraft

- Execution by burning

- Pierre de Lancre (conductor of a bloody witch-hunt in Labourd)

- List of people executed for witchcraft

- North Berwick witch trials

- Ramsele witch trial

- Scapegoating

- St Osyth Witches

- "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street" (Episode from the original series The Twilight Zone)

- Torsåker witch trials

- Torture of witches

- Trial by ordeal

- Würzburg witch trial

- Satanic ritual abuse

References

- ^ Erich Goode; Nachman Ben-Yehuda (2010). Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance. Wiley. p. 195.

- ^ Lois Martin (2010). A Brief History of Witchcraft. Running Press. p. 5.

- ^ a b The most common estimates are between 40,000 and 60,000 deaths. Brian Levack (The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe) multiplied the number of known European witch trials by the average rate of conviction and execution, to arrive at a figure of around 60,000 deaths. Anne Lewellyn Barstow (Witchcraze) adjusted Levack's estimate to account for lost records, estimating 100,000 deaths. Ronald Hutton (Triumph of the Moon) argues that Levack's estimate had already been adjusted for these, and revises the figure to approximately 40,000.

- ^ Jean Sybil La Fontaine, Speak of the devil: tales of satanic abuse in contemporary England, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-521-62934-8 34–37.

- ^ Behringer (2004), 50.

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia article on Witchcraft, last Retrieved 31 March 2006. There is some discrepancy between translations; compare with that given in the Catholic Encyclopedia article on Witchcraft (Retrieved 31 March 2006), and the L. W. King translation (Retrieved 31 March 2006).

- ^ Behringer (2004), 48–50.

- ^ Garnsey, Peter; Saller, Richard P. (1987). The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. pp. 168–174. ISBN 0-520-06067-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "witch" here translates the Hebrew מכשפה, and is rendered φαρμακός in the Septuagint.

- ^ "those that have familiar spirits": Hebrew אוב, or ἐγγαστρίμυθος "ventriloquist, soothsayer" in the Septuagint; "wizards": Hebrew ידעני or γνώστης "diviner" in the Septuagint.

- ^ Jordanes. The Origin and Deeds of the Goths. pp. § 24.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Early British Isles..

- ^ Medieval Sourcebook: The Anglo-Saxon Dooms, 560–975.

- ^ ["Witchcraft" article, Catholic Encyclopaedia, 1911, on the New Advent website]

- ^ [Migne, Patrologia Latina, CIV, 147]

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, A History of Medieval Christianity (173).

- ^ See Franco Mormando, The Preacher's Demons: Bernardino of Siena and the Social Underworld of Early Renaissance Italy, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1999, Chapter 2.

- ^ Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe, (49)

- ^ Jolly, Raudvere, & Peters(eds.), "Witchcraft and magic in Europe: the Middle Ages", page 241 (2002)

- ^ The Dark Side of Christian History by Helen Ellerbe.

- ^ Meewis, Wim (1992) De Vierschaar, Uitgevering Pelckmans, p. 115.

- ^ H. C. Erik Midelfort, “Heartland of the Witchcraze: Central and Northern Europe,” History Today 31 (February 1981): 27–31.

- ^ H. C. Erik Midelfort, Witch Hunting in Southwestern Germany 1562–1684,1972,71.

- ^ Behringer (2004), p. 83.

- ^ Follow the Pendle Witches trail BBC Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.masslive.com/history/index.ssf/2011/05/springfields_375th_from_puritans_to_presidents.html

- ^ Fraden, Judith Bloom, Dennis Brindell Fraden. The Salem Witch Trials. Marshall Cavendish. 2008. p. 15.

- ^ Wallace, Peter G. (2004). The Long European Reformation. New York, NY: PALGRAVE MACMILLAN. pp. 210–215. ISBN 978-0-333-64451-5.

- ^ "Estimates of executions". Based on Ronald Hutton's essay Counting the Witch Hunt.

- ^ Charles Alva Hoyt, Witchcraft, Southern Illinois University Press, 2nd edition, 1989, pp. 66–70, ISBN 0-8093-1544-0.

- ^ Gaskill, Malcolm Witchcraft, a very short introduction, Oxford University Press, 2010, p.65

- ^ a b William Monter: Witch trials in Continental Europe, (in:) Witchcraft and magic in Europe, ed. Bengst Ankarloo & Stuart Clark, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 2002, pp 12 ff. ISBN 0-8122-1787-X; and Levack, Brian P. The witch hunt in early modern Europe, Third Edition. London and New York: Longman, 2006.

- ^ Gaskill, Malcolm Witchcraft, a very short introduction, Oxford University Press, 2010, p.76

- ^ Rapley, Robert (1998). A case of witchcraft: the trial of Urbain Grandier.

- ^ a b Gibson, M (2006). "Witchcraft in the Courts". In Gibson, Marion (ed.). Witchcraft And Society in England And America, 1550–1750. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-8264-8300-3.

- ^ Summers, M (2003). Geography of Witchcraft. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 153–60. ISBN 0-7661-4536-0.

- ^ The Holocaust; or the Witch of Monzie.

- ^ "Graemes of Inchbrakie – The Witch's Relic".

- ^ Template:Nl icon "Laatste executie van heks in Borculo". Archeonnet.nl. 11 October 2003. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ "Last witch executed in Denmark". executedtoday.com. 4 April 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ Timeline The Last Witchfinder

- ^ Template:De icon Anna Schwaegelin at Historicum.net.

- ^ [2].[clarification needed]

- ^ "Last witch in Europe cleared". Swissinfo.ch. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ Mohammed A. Diwan: Conflict between state legal norms and norms underlying popular beliefs: witchcraft in africa as a case study; in: 14 Duke J. of Comp. & Int'l L. 351.

- ^ "Congo witch-hunt's child victims". BBC News. 22 December 1999. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- ^ a b "Tanzania arrests 'witch killers'". BBC News. 23 October 2003. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

It is believed that any aged, old woman with red eyes is a witch

- ^ A Modern Movement of Witch Finders Audrey I Richards (Africa: Journal of the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures, Ed. Diedrich Westermann.) Vol VIII, 1935, published by Oxford University Press, London.

- ^ Christian responses to witchcraft and sorcery.

- ^ "Whereas witchcraft cases in the colonial era, especially in former British Central Africa, were based on the official dogma that witchcraft is an illusion (so that people invoking witchcraft would be punished as either impostors or slanderers), in contemporary legal practice in Africa witchcraft appears as a reality and as an actionable offence in its own right." Wim van Binsbergen, Witchcraft in Modern Africa (2002).

- ^ section 251 of the Cameroonian penal code (26 August 2004). Two other provisions of the penal code [translation] "state that witchcraft may be an aggravating factor for dishonest acts" (Afrik.com 26 Aug 2004). A person convicted of witchcraft may face a prison term of 2 to 10 years and a fine. Cameroon: Witchcraft in Cameroon; tribes or geographical areas in which witchcraft is practised; the government's attitude, UNHCR (2004).

- ^ Mob burns to death 11 Kenyan "witches".

- ^ "The Gambia: Hundreds accused of "witchcraft" and poisoned in government campaign"

- ^ "Witch-Hunt in Gambia".

- ^ Studia Instituti Anthropos, Vol. 41. Anthony J. Gittins : Mende Religion. Steyler Verlag, Nettetal, 1987. p. 197.

- ^ Studia Instituti Anthropos, Vol. 41. Anthony J. Gittins : Mende Religion. Steyler Verlag, Nettetal, 1987. p. 201.

- ^ Womensnews.org.

- ^ The Hindu, Nearly 200 women killed every year after being branded witches, 26 July 2010. Herald Sun, 200 'witches' killed in India each year – report, 26 July 2010.

- ^ A Jharkhand case publicized in international media in 2009 concerned five Muslim women. BBC News, 30 October 2009.

- ^ Channel14.com.

- ^ Precarious Justice – Arbitrary Detention and Unfair Trials in the Deficient Criminal Justice System of Saudi Arabia. Human Rights Watch. 2008. p. 143.

- ^ "Distance witch finally caught; 118 detained this year". Saudi Gazette. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: Witchcraft and Sorcery Cases on the Rise" (Press release). 24 November 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "King Abdullah urged to spare Saudi 'witchcraft' woman's life". The Times. 16 February 2008.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Letter to HRH King Abdullah bin Abd al-'Aziz Al Saud on "Witchcraft" Case" (Press release). Human Rights Watch. 12 February 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Saudi executes Egyptian for practising 'witchcraft'". ABC News. 3 November 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Sudanese man facing execution in Saudi Arabia over 'sorcery' charges". Afrik News. 15 May 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Lebanese TV host Ali Hussain Sibat faces execution in Saudi Arabia for sorcery". The Times. 2 April 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Lebanese PM should step in to halt Saudi Arabia 'Sorcery' execution" (Press release). Amnesty International. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Saudi court rejects death sentence for TV psychic". CTV News. Associated Press. 13 November 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: Woman Is Beheaded After Being Convicted of Witchcraft". The New York Times. Agence France-Presse. 12 December 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Saudi man executed for 'witchcraft and sorcery'

- ^ J. F. Carter, What we are about to Receive (xviii. 204): "Once the election is over [...] we shall quietly lay aside our witch hunting."

- ^ Liev Schreiber (2 May 2010). America: The Story of Us – Division (Television). Nutopia.

- ^ a b Jensen, Gary F. (2007). The Path of the Devil. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. Ch. 8. ISBN 0-7425-4697-7.

- ^ Murphy, Brenda (1999). Congressional Theatre. Cambridge University Press. pp. Ch. 4. ISBN 0-521-89166-3.

- ^ de Young, Mary (2004). The Day Care Ritual Abuse Moral Panic. Jefferson, North Carolina, United States: McFarland and Company. ISBN 0-7864-1830-3.

- ^ "Modern witch hunt – child abuse charges". PEDIATRICS. 93 (4). American Academy of Pediatrics: 635. 1 April 1994. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Hans Sebald (1995). Witch-children: From Salem Witch-Hunts to Modern Courtrooms. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-0-87975-965-0.

- ^ Tariq Tahir (15 May 2002). "Scandal of child abuse 'witch-hunt'". Daily Post. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "Abuse witch-hunt traps innocent in a net of lies". The Observer. 26 November 2000. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Witchcraft Bibliography Project Online with primary and secondary sources worldwide, University of Glamorgan, UK

- Behringer, Wolfgang. Witches and Witch Hunts: A Global History. Malden Massachusetts: Polity Press, 2004.

- Briggs, Robin. 'Many reasons why': witchcraft and the problem of multiple explanation, in Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe. Studies in Culture and Belief, ed. Jonathan Barry, Marianne Hester, and Gareth Roberts, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Burns, William E. Witch hunts in Europe and America: an encyclopedia (2003)

- Cohn, Norman. Europe's Inner Demons: The Demonization of Christians in Medieval Christendom, Revised Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993.

- Durrant, Jonathan B. Witchcraft, Gender, and Society in Early Modern Germany, Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- Golden, William, ed. Encyclopedia of Witchcraft: The Western Tradition (4 vol. 2006) 1270pp; 758 short essays by scholars.

- Goode, Erich; Ben-Yahuda, Nachman (1994). Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18905-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Klaits, Joseph. Servants of Satan: The Age of the Witch Hunts. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985

- Levack, Brian P. The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661–1662, The Journal of British Studies, Vol.20, No, 1. (Autumn, 1980), pp. 90–108.

- Levack, Brian P. The witch hunt in early modern Europe, Third Edition. London and New York: Longman, 2006.

- Macfarlane, Alan. Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England: A regional and Comparative Study. New York and Evanston: Harper & Row Publishers, 1970.

- Midlefort, Erick H.C. Witch Hunting in Southeastern Germany 1562–1684: The Social and Intellectual Foundation. California: Stanford University Press, 1972. ISBN 0-8047-0805-3

- Monter, William. "The Historiography of European Witchcraft: Progress and Prospect," Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol 2 (1972), 435–451.

- Oberman, H. A., J. D. Tracy, Thomas A. Brady (eds.), Handbook of European History, 1400–1600: Visions, Programs, Outcomes (1995) ISBN 90-04-09761-9

- Oldridge, Darren (ed.), The Witchcraft Reader (2002) ISBN 0-415-21492-0

- Poole, Robert. The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories (2002) ISBN 0-7190-6204-7

- Purkiss, Diane. "A Holocaust of One's Own: The Myth of the Burning Times." Chapter in The Witch and History: Early Modern and Twentieth Century Representatives New York, NY: Routledge, 1996, pp. 7–29.

- Robisheaux, Thomas. The Last Witch of Langenburg: Murder in a German Village. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. (2009) ISBN 978-0-393-06551-0

- Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World, Random House, 1996. ISBN 0-394-53512-X

- Thurston, Robert. The Witch Hunts: A History of the Witch Persecutions in Europe and North America. Pearson/Longman, 2007.

- Purkiss, Diane. The Bottom of the Garden, Dark History of Fairies, Hobgoblins, and Other Troublesome Things. Chapter 3 Brith and Death: Fairies in Scottish Witch-trials New York, NY: New York University Press, 2000, pp. 85–115.

- West, Robert H. Reginald Scot and Renaissance Writings. Boston: Twayne Publishers,1984.

- Briggs, K.M. Pale Hecate’s Team, an Examination of the Beliefs on Witchcraft and Magic among Shakespeare’s Contemporaries and His Immediate Successors. New York: The Humanities Press, 1962.

External links

- The Stages of a Witch Trial — a series of articles by Jenny Gibbons.

- 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia entry on "Witchcraft"

- Jenny Gibbons (1998). Draeconin.com. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- The Decline and End of Witch Trials in Europe by James Hannam

- Witch Trials

- Dame Alice le Kyteler, convicted of witchcraft in Kilkenny, Ireland, 1324

- Elizabethan Superstitions in the Elizabethan Period by Linda Alchin

- Douglas Linder (2005), A Brief History of Witchcraft Persecutions before Salem

- Witchcraft in Scotland