Young Goodman Brown

| "Young Goodman Brown" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publication | |

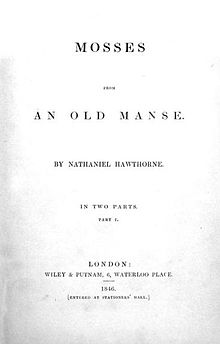

| Published in | Mosses from an Old Manse |

| Publication date | 1835 (anonymously) in The New-England Magazine; 1846 (under his own name) in Mosses from an Old Manse |

"Young Goodman Brown" is a short story published in 1835 by American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne. The story takes place in 17th-century Puritan New England, a common setting for Hawthorne's works, and addresses the Calvinist/Puritan belief that all of humanity exists in a state of depravity, but that God has destined some to unconditional election through unmerited grace. Hawthorne frequently focuses on the tensions within Puritan culture, yet steeps his stories in the Puritan sense of sin. In a symbolic fashion, the story follows Young Goodman Brown's journey into self-scrutiny, which results in his loss of virtue and belief.[1]

Plot

The story begins at dusk in Salem Village, Massachusetts as young Goodman Brown leaves Faith, his wife of three months, for some unknown errand in the forest. Faith pleads with her husband to stay with her, but he insists that the journey must be completed that night. In the forest he meets an older man, dressed in a similar manner and bearing a physical resemblance to himself. The man carries a black serpent-shaped staff. Deeper in the woods, the two encounter Goody Cloyse, an older woman, whom Young Goodman had known as a boy and who had taught him his catechism. Cloyse complains about the need to walk; the older man throws his staff on the ground for the woman and quickly leaves with Brown.

Other townspeople inhabit the woods that night, traveling in the same direction as Goodman Brown. When he hears his wife's voice in the trees, he calls out but is not answered. He then runs angrily through the forest, distraught that his beautiful Faith is lost somewhere in the dark, sinful forest. He soon stumbles upon a clearing at midnight where all the townspeople assembled. At the ceremony, which is carried out at a flame-lit altar of rocks, the newest acolytes are brought forth—Goodman Brown and Faith. They are the only two of the townspeople not yet initiated. Goodman Brown calls to heaven and Faith to resist and instantly the scene vanishes. Arriving back at his home in Salem the next morning, Goodman Brown is uncertain whether the previous night's events were real or a dream, but he is deeply shaken, and his belief he lives in a Christian community is distorted. He loses his faith in his wife, along with all of humanity. He lives his life an embittered and suspicious cynic, wary of everyone around him. The story concludes: "And when he had lived long, and was borne to his grave... they carved no hopeful verse upon his tombstone, for his dying hour was gloom."

Development and publication history

The story is set during the Salem witch trials, at which Hawthorne's great-great-grandfather John Hathorne was a judge, guilt over which inspired the author to change his family's name, adding a "w" in his early twenties, shortly after graduating from college.[2] In his writings Hawthorne questioned established thought—most specifically New England Puritanism and contemporary Transcendentalism. In "Young Goodman Brown", as with much of his other writing, he utilizes ambiguity.[3]

"Young Goodman Brown" was first published in the Boston-based The New-England Magazine in its April 1835 issue. It did not include Hawthorne's name and was instead credited "by the author of 'The Gray Champion'".[4] It was finally published with the author's name in Mosses from an Old Manse in 1846.

Analysis

"Young Goodman Brown" is often characterized as an allegory about the recognition of evil and depravity as the nature of humanity.[5] Much of Hawthorne's fiction, such as The Scarlet Letter, is set in 17th-century colonial America, particularly Salem Village. To convey the setting, he used literary techniques such as specific diction, or colloquial expressions. Language of the period is used to enhance the setting. Hawthorne gives the characters specific names that depict abstract pure and wholesome beliefs, such as "Young Goodman Brown" and "Faith". The characters' names ultimately serve as a paradox in the conclusion of the story. The inclusion of this technique was to provide a definite contrast and irony. Hawthorne aims to critique the ideals of Puritan society and express his disdain for it, thus illustrating the difference between the appearance of those in society and their true identities.[6][7][8]

Literary scholar Walter Shear writes that Hawthorne structured the story in three parts. The first part shows Goodman Brown at his home in his village integrated in his society. The second part of the story is an extended dreamlike/nightmare sequence in the forest for a single night. The third part shows his return to society and to his home, yet he is so profoundly changed that in rejecting the greeting of his wife Faith, Hawthorne shows Goodman Brown has lost faith and rejected the tenets of his Puritan world during the course of the night.[9]

The story is about Brown's loss of faith as one of the elect, according to scholar Jane Eberwein. Believing himself to be of the elect, Goodman Brown falls into self-doubt after three months of marriage which to him represents sin and depravity as opposed to salvation. His journey to the forest is symbolic of Christian "self-exploration" in which doubt immediately supplants faith. At the end of the forest experience he loses his wife Faith, his faith in salvation, and his faith in human goodness.[6]

Literary significance and reception

Herman Melville said "Young Goodman Brown" was "as deep as Dante" and Henry James called it a "magnificent little romance".[10] Hawthorne himself believed the story made no more impact than any of his tales. Years later he wrote, "These stories were published... in Magazines and Annuals, extending over a period of ten or twelve years, and comprising the whole of the writer's young manhood, without making (so far as he has ever been aware) the slightest impression on the public".[11] Contemporary critic Edgar Allan Poe disagreed, referring to Hawthorne's short stories as "the products of a truly imaginative intellect".[12]

Stephen King has referred to "Young Goodman Brown" as "one of the ten best stories written by an American". He calls it his favorite story by Hawthorne and cites it as an inspiration for his O. Henry Award-winning short story, "The Man in the Black Suit".[13]

Modern scholars and critics generally view the short story as an allegorical tale written to expose the contradictions in place concerning Puritan beliefs and societies.[citation needed] However, there have been many other interpretations of the text including those who believe Hawthorne sympathizes with Puritan beliefs.[citation needed] Author Harold Bloom comments on the variety of explanations.[citation needed]

Adaptations

A 1972 short film directed by Donald Fox is based on the story. It features actors Mark Bramhall, Peter Kilman, and Maggie McOmie.

In 1982, the story was adapted for the CBC radio program Nightfall.

This is the only work of Hawthorne's included in the Library of America's 2009 anthology American Fantastic Tales: Terror and the Uncanny from Poe to the Pulps.

In 2011, playwright Lucas (Luke) Krueger, adapted the story for the stage. It was produced by Northern Illinois University. In 2012, Playscripts Inc. published the play. It has since been produced by several companies and high schools.

The 2015 music video for the Brandon Flowers song "Can't Deny My Love" is based on Hawthorne's story, with Flowers starring as the Goodman Brown figure and Evan Rachel Wood as his wife.

Comic artist Kate Beaton satirized the story in a series of comic strips for her webcomic Hark! A Vagrant, which focuses on mocking Goodman Brown's obsessive, black-and-white morality and his hypocrisy toward his wife and friends.[14]

References

- ^ Summary of Young Goodman Brown, articlemyriad.com; accessed December 23, 2014.

- ^ McFarland, Philip. Hawthorne in Concord. New York: Grove Press, 2004: 18. ISBN 978-0-8021-1776-2.

- ^ Gray, Richard. A History of American Literature. p. 200

- ^ Brown, Nina E. A Bibliography of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1905: 57.

- ^ Bell, Michael Davitt. Hawthorne and the Historical Romance of New England. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1971, p. 77; ISBN 978-0-691-06136-8

- ^ a b Eberwein, Jane Donahue. "My Faith is Gone! 'Young Goodman Brown' and Puritan conversion", Nathaniel Hawthorne's Young Goodman Brown (2005). Bloom, Harold, (ed.) Chelsea House; ISBN 978-0-7910-8124-2, pp. 20–27.

- ^ Easterly, Joan Elizabeth. "Lachrymal Imagery in Hawthorne's 'Young Goodman Brown'", Studies in Short Fiction 28, no. 3 (Summer 1991). Quoted as "Lachrymal Imagery in Hawthorne's 'Young Goodman Brown'", Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations. New York: Chelsea House Publishing, 2005. Bloom's Literary Reference Online

- ^ Mayr, Julia Gaunce; Gaunce, Suzette (2004). The Broadview Anthology of Short Fiction. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

- ^ Shear, Walter. "Cultural Fate and Social Freedom in Three American Short Stories", Nathaniel Hawthorne's Young Goodman Brown (2005). Bloom, Harold (ed.), Chelsea House; ISBN 978-0-7910-8124-2, pp. 63–66.

- ^ Miller, Edwin Haviland. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991: 119; ISBN 978-0-87745-332-1.

- ^ McFarland, Philip. Hawthorne in Concord. New York: Grove Press, 2004: 22. ISBN 978-0-8021-1776-2.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998: 334; ISBN 978-0-8018-5730-0.

- ^ King, Stephen. Everything's Eventual. New York: Pocket Books, 2007: pp. 69–70

- ^ harkavagrant.com

External links

- Young Goodman Brown at Project Gutenberg

- Reading of Young Goodman Brown by Stuff You Should Read Podcast

Young Goodman Brown public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Young Goodman Brown public domain audiobook at LibriVox