Zoellner Quartet

Zoellner Quartet | |

|---|---|

The Zoellners, from a 1917 publication[1] | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Brooklyn, New York, US |

| Years active | First quarter, 20th century |

The Zoellner Quartet was a string quartet active during the first quarter of the 20th century. It was once described as "the most celebrated musical organization in the West which devotes its energies exclusively to the highest class of chamber music".[2] After training in Europe, the group toured widely throughout the United States in its prime years. Although all members were natives of Brooklyn, New York, the ensemble formed a strong early association with Belgium and in publicity often billed itself as "The Zoellner Quartet of Brussels"; its ultimate base of operations was in California. With one brief interruption at the end of World War I, the membership remained constant throughout the quartet's existence: Joseph Zoellner and his children Antoinette; Amandus; and Joseph, Jr. A second "Zoellner Quartet" was later formed by Joseph, Jr. and three unrelated musicians.[3]

Formation and European career

[edit]Joseph Zoellner founded the quartet, most likely in 1903[4] but possibly in 1904,[3] in Brooklyn, where he operated a music school.[5] From the group's founding until 1906 the members lived in Stockton, California, where he had opened a similar school[5] or music store.[4] Under sponsorship of Ethel Crocker, wife of San Francisco banking magnate William Henry Crocker,[3] the Zoellners then went to Belgium for several years to hone their skills with the celebrated Belgian pedagogue César Thomson,[4] who had also taught three members of the group's contemporary, the Flonzaley Quartet.[6]

The Zoellner Quartet's first European appearances were at César Thomson's private soirees, but the group soon began performing more widely in Belgium and in Paris and Berlin.[5] Of particular note, late in the period of its European residency, the mother[7] of King Albert I of Belgium presented the quartet with a gold medal specially struck by goldsmith C.H. Samuels after the group performed as royal guests of the Belgian king and queen in 1911.[3]

North American career

[edit]Following its journeyman years in Europe, the quartet in the 1912–1913 season[8] embarked on what would be a constant round of activity in Canada and the United States, keeping to an intense schedule during annual coast-to-coast tours.[9] During an early 1919 tour of western Canada starting in Victoria, British Columbia, in the final city of Winnipeg the quartet gave its 500th performance in six years of touring;[10] by 1921, its total was reported to be 1,100 performances upon return from a tour of the US East and Midwest, within a week of which it was scheduled to perform yet again in Los Angeles.[11] In nine weeks ending in late March 1923 alone, the quartet performed 46 concerts in connection with its twelfth tour of the US East.[12] In later years, Amandus was said to have participated in more than 2,500 performances during his career with the quartet.[13] The quartet prided itself on keeping to non-stop schedules in its numerous transcontinental tours without letup or delays, even when on one occasion in 1921 Joseph, Jr. fell in Topeka, Kansas, and was relegated to use of a crutch for a few days.[11]

In its North American years, as its celebrity grew, the quartet's members naturally associated with notable musicians such as Ernestine Schumann-Heink, Mischa Elman, and—not surprisingly, given the quartet's Belgian connections—Eugène Ysaÿe.[3] The group also, however, had less obvious associations with the famous of its day. In one colorful incident, as the quartet toured during the 1916–1917 season, it crossed paths with the famous deafblind author, activist, and lecturer Helen Keller and her teacher and companion Anne Sullivan in Oklahoma City, where Keller was scheduled for a lecture. Keller proposed as an experiment that the quartet should play for her, to determine whether she could sense music; readily acceding to her request, the quartet played music including the celebrated second movement, andante cantabile, from Tchaikovsky's String Quartet no. 1 in D Major, op. 11, as she held her fingertips lightly on a resonant tabletop. Keller quickly sensed the musical vibrations, swaying in time, alternately crying and smiling.[14] Afterward, Keller reacted as follows:[15]

When you play to me I see and hear and feel many things that I cannot easily put into words. I feel the sweep and surge and mighty pulse of life. Oh, you are masters of a wondrous art, subtle and superfine. When you play to me immediately a miracle is wrought, sight is given the blind, and deaf ears hear sweet, strange sounds.

Each note is a picture, a fragrance, the flash of a wing, a lovely girl with pearls in her hair, a group of exquisite children dancing and swinging garlands of flowers—a bright mingling of colors and twinkling feet. There are notes that laugh and kiss and sigh and melt together. And notes that weep and rage and fly apart like shattered crystal.

But mostly the violins sing of lovely things—woods and streams and sun-kissed hills, the faint sound of tiny creatures flitting about in the grass and under the petals of the flowers, the noiseless stirring of shadows in my garden, and the soft breathings of shy things that light on my hand for an instant, or touch my hair with their wings. O, yes! and a thousand, thousand other things that I cannot describe come thronging through my soul when the Zoellner Quartet plays to me.

For his part, Joseph Zoellner rather more prosaically stated that he and the rest of the quartet felt they had been playing to a "responsive instrument" and were impressed with Keller's ability to interpret the music. For instance, although no one had told her the Tchaikovsky work supposedly had its basis in an old fisherman's song, Keller described it as evoking the sea and the ocean breeze on her face.[14]

More than a dozen years later, in January 1931, Albert Einstein, who was then engaged in research at the California Institute of Technology, visited the Zoellner family's conservatory and played violin with members of the quartet in music of Beethoven and Mozart. The following year, a few days before Einstein sailed for what would be his last visit to Germany, he presented Joseph Zoellner with an autographed photograph as a memento of the occasion.[3][16]

In the United States, as in Europe, the quartet was no stranger to the major cultural centers. Upon its return to America it first performed in New York City at Aeolian Hall on January 7, 1914, when, demonstrating a recurrent predilection for adventurously mixing music old and new, the program featured Glazounov's Suite in C Major, op. 35; Haydn's Quartet in G Major, op. 76 no. 1; and the Romantische Serenade of Jan Brandts Buys, which had been heard in New York on only one prior occasion.[17] The quartet's sixth transcontinental tour of the United States and Canada, announced in late 1917, included two performances in New York City and others in Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago.[18]

The quartet saw its mission as broader than performing in such major venues, however; its aim was to widen the audience for chamber music, which the Zoellners considered an intimate form with personal appeal to the audience, even one lacking cultured appreciation of music. Thus, with missionary zeal, they consistently performed in towns well removed from the regular concert circuit, often ones that had never been visited by a string quartet.[19] Toward the end of its 1921 season, for instance, the quartet had already committed to return engagements in Topeka and Wichita, Kansas; St. Joseph, Missouri; Dubuque, Iowa; Richmond, Indiana; and Peoria, Illinois.[11] Pursuing this educational goal, the Zoellners performed in such unconventional surroundings as trains and an Illinois insane asylum.[3] In 1916 the quartet presented Charles Sanford Skilton's "Indian Dances" to traditional audiences in Boston and also to five hundred Native Americans in Oklahoma, in each case receiving a standing ovation.[20]

In parallel with this diversity of performance locales, the quartet appears to have cultivated qualities calculated to please both cosmopolitan and discerning but less urbanized audiences and critics. Following the 1914 Aeolian Hall performance, a review in The New York Times commended the group's tone, intonation, and ensemble,[17] while, tellingly, the Lawrence, Kansas Lawrence Journal-World in 1917 described the quartet as follows: "The Zoellner Quartet is a great favorite with Lawrence audiences, as its programs suit the tastes of the average concert-goer, and this without the inclusion of superficial music."[21]

Giving an idea of how the quartet assembled its programs and the widely scattered smaller venues in which it played on what were tight schedules in those days before air travel, some of its documented performances in 1917 were as follows:

- The performance in Lawrence, scheduled for April 5, included the String Quartet no. 1 in B-Flat on Maori (New Zealand) Themes by Alfred Hill; the adagio from a Mozart quartet in B-Flat major; the scherzo from Alexander Glazunov's Quartet no. 4 in A Minor; a piano quintet by Edgar Stillman Kelley, with Carl Preyer, head of the piano department at the local School of Fine Arts, at the keyboard; and arrangements of "Cherry Ripe" by Frank Bridge and of a German folk song by Kaessmayer.[22]

- Five days later, in Appleton, Wisconsin, the Quartet performed the same Hill quartet, Glazunov scherzo, and folk song arrangements, to which were added the nocturne from the Second Quartet by Alexander Borodin; the lullaby from a quartet by Skilton; and two works presented by subsets of the quartet: Sinding's Serenade for Two Violins and Piano, featuring Atoinette and Amandus on violins and Joseph, Jr. on piano, and Dvořák's Ballade in D Minor for Violin and Piano, performed by Amandus, presumably again with Joseph, Jr. as pianist.[23]

- On November 5, the quartet performed at the North Dakota Agricultural College, now North Dakota State University. The program included the "American" Quartet of Antonín Dvořák; "Deep River" (arr. Burleigh and Kramer) and a Russian folksong (arr. Kaessmeyer); a suite for two violins and piano by Emánuel Moór, played by Antoinette and Amandus with Joseph, Jr. on the piano; and Károly Thern's "Genius Loci" and Skilton's "War Dance" as encores, both by request.[24]

- A week later, on November 12, the quartet was in Columbia, Missouri, to present the season's second Phi Mu Alpha concert at the University Auditorium. The works on the program again included the "American" Quartet and also Haydn's Quartet in C Major, op. 74, no. 1; Two Sketches for String Quartet by Eugene Goossens; and Quartet no. 2 in A Major, op. 28 by Eduard Nápravník.[25]

From the beginning of its US career, the quartet also performed under the auspices of various performing arts societies and series, academic and civic, scattered across the United States. Among these appearances were the following:

- June 26, 1912, 24th annual convention of the New York State Music Teachers' Association at Columbia University. Marie Rappold and Frank Croxton also performed, and David Bispham and Reginald de Koven discussed presentation of opera in English.[26]

- February 4, 1914, Saturday Morning Musical Club at the Temple of Music and Art in Tucson, Arizona.[27]

- 1915–16 season, fourth formal season of the Tuesday Morning Musical Club Concert Series, now Tuesday Musical, in Omaha, Nebraska; the quartet made a return appearance in the 1919–1920 season.[28]

- Between 1911 and 1920, performance series of the Schubert Club of St. Paul, Minnesota.[29]

The performances noted above suggest the Zoellner Quartet's breadth of repertory. This musical catholicity did not escape critical notice, as, for example, in a review by Florence Lawrence[a] in the Los Angeles Examiner of July 26, 1919: "[T]he brilliant closing concert of the Zoellner chamber music season last night ... proved the climax in this unusual course, in which modern and classical works have been especially well contrasted, and testified vividly to the fine artistry of the musicians. It was a great personal achievement for the artists." Occasioning that review was the conclusion of a marathon series of ten weekly recitals from May 23 to July 25, 1919, at the Ebell Club Auditorium in Los Angeles. Works presented over the course of this venture, ranging from Baroque to then-contemporary, were as follows:[8]

- Beethoven: Quartets no. 4 in C Minor, op. 18 no. 4; no. 6 in B-Flat Major, op. 18 no. 6; and no. 10 in E-Flat Major ("Harp")

- Borodin: Quartet No. 2 in D Major

- Brandts-Buys: Romantic Serenade, Op. 25

- Bridge: Noveletten; (arr.) Two Old English Songs. The quartet had begun including the Noveletten in its programs during its 1916 tour of Canada and the United States.[30]

- Debussy: Quartet in G Minor, op. 10

- Dohnányi: Quartet no. 2 in D-Flat Major, op. 15

- Dvořák: Quartet no. 12 in F, op. 96 ("American")

- Fasch: Sonate A Quatre

- Franck: Quartet in D Major

- Glazounov: Suite in C Major, Op. 35

- Eugene Goossens: Two Sketches, op. 15

- Handel: Sonata in G Minor for two violins and piano

- Haydn: Quartets op. 51 ("Seven Last Words of Christ"); in C Major, op. 74 no. 1; and in G Major, op. 76 no. 1

- Hill: Quartet no. 1 in B-Flat

- Jean Baptiste Loeillet (1653–1728):[31] Sonate a Trois for violin, viola, and piano

- Witold Maliszewski: Quartet no. 1 in F Major, op. 2

- Milhaud: Quartet in C

- Jules Mouquet: Quartet no. 1 in C Minor, op. 3

- Mozart: Quartets no. 16 in E-Flat Major, K. 428; no. 17 in B-Flat Major, K. 458 ("Hunt"); and no. 21 in D Major, K. 575 ("Violet")

- Eduard Nápravník: Quartet no. 2 in A Major, op. 28

- Schubert: Quartet in E-Flat Major, D. 87 (op. 125 no. 1)

- Schumann: Quartet in A Major, op. 41 no. 3

Conservatory

[edit]In 1922, the family, which had resided at 909 St. Marks Ave. in New York City and summered in Wrentham, Massachusetts,[32] shifted its base of operations to California, where it had already performed actively, and settled in Los Angeles. There the Zoellners opened the Zoellner Conservatory of Music, which eventually added branches in Hollywood and Burbank, California;[3] it was still active as of 1942, well after the quartet's retirement, when the Hollywood branch conferred an honorary Doctor of Music Degree on bandmaster Earl Irons.[33] Upon its resettlement, the quartet continued to be an active part of musical life in its adopted home. Nor did it restrict its educational endeavors to the activities of its own school: the quartet participated in the Behymer Philharmonic Series, a youth promotion initiative of low-priced concerts, four for $1.00, organized by Lynden Behymer.

The quartet retired in 1925.[3] As noted below, however, members of the family continued their involvement in music, both through the conservatory and through various institutions of higher learning, and evidently they still performed together occasionally, at least for a time, in that context.[34] An appearance in a radio broadcast on station KHJ, Los Angeles, was scheduled for as late as November 24, 1927,[35] and the group's informal performance with Albert Einstein took place in 1931.[16]

Premieres and dedications

[edit]The Zoellner Quartet gave premieres or was dedicatee of works by a number of contemporary composers. Among them were the following:

- Arthur Farwell, acting at the suggestion of Joseph Zoellner, wrote a string quartet titled "The Hako" in 1922 and dedicated it to the Zoellner Quartet, which performed it in 1923 at the Ojai Music Festival in Ojai, California.[36]

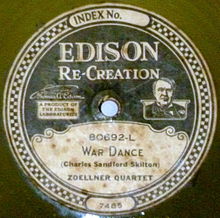

- Charles Sanford Skilton dedicated his Two Indian Dances to the Zoellner Quartet, which premiered them in January 1916. Carl Fischer Music published the works a year later, by which time Skilton had orchestrated them, and later still he incorporated them into his Suite Primeval.[36] The Zoellner Quartet's Edison recording of the second number, "War Dance," can be heard via the link above.

- Eugene Goossens wrote a quartet for the Zoellners; they programmed it for their Eastern US tour in early 1919.[2]

- The Quartet premiered "Impressions of a Rainy Day," a suite for quartet by Roy Harris, on March 15, 1926, at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles.[37]

- During its 1923 tour of the eastern United States, the Quartet gave the American premiere of Joseph Jongen's Serenade Tendre.[12]

- Also receiving its American premiere during the 1923 tour was a Fantasie for string quartet by Marion Frances Ralston.[12]

Personnel

[edit]

The quartet's configuration was unusual, particularly for its day. Being, in the words of one 1917 article, "about the only string quartet in existence" to "honor" a female with the first violinist's chair in an otherwise entirely male ensemble,[24] it drew public attention, as when, after a concert in Quebec, a suffragette leapt to her feet and cried, "I never thought I'd live to see it, but it comes to pass—one woman leading three men. Votes for women!"[19] Moreover, the founder and most senior member, both by age and experience, served as violist. All three of the quartet's junior members studied first with their father before continuing studies in Brussels.

- Antoinette Zoellner was first violinist. Sources differ on her date of birth.[38][5] She studied with her father and, from 1907 to 1912,[38] with César Thomson;[5] she also studied singing with Raimund von zur-Mühlen. As of 1920, she shared a residence in Los Angeles with her father and brother Joseph, Jr.[38] She died on March 11, 1962.

- Amandus Carl Zoellner, second violinist, was born on November 7, 1892[5][13] and died on June 14, 1955. He and his wife, Ruth, née Koehler, had at least two children, daughters Ruth and Marjorie;[13] the former did not follow her father into music but eventually fell heir to the quartet's archives and arranged for their institutional preservation, with the scores going to Scripps College in Claremont, California, and memorabilia and scrapbooks to UCLA.[3] When not playing the violin, Amandus enjoyed photography and fishing.[13]

- Joseph Zoellner, the quartet's violist and father of the other three members, was born on February 2, 1862, and died on January 24, 1950. Initially, he trained as a violinist, first in New York and then in Germany. By the time he founded the quartet, he was a musical veteran, having already served as first violinist of the Theodore Thomas Orchestra in New York. He also gave initial training to all three other members of the quartet before their studies in Belgium.[38]

- Joseph Zoellner, Jr., cellist for nearly the entire life of the quartet, was born on October 26, 1886, and died in September 1964.[39] Zoellner was a 1910 graduate of the Royal Conservatory of Brussels in both piano, in which he took honors,[5] and cello;[7] his teachers included Jean Gérardy for cello, Paul Gilson for harmony, and Arthur de Greef for piano.[5] Joseph, Jr. was the sole member to leave the quartet, when for a few months at the end of World War I he served as a corporal in the United States Army;[2] the quartet's concert manager, Harry Culbertson of Chicago, likewise enlisted at that time. Both men had returned to civilian life by early 1919.[40]

- Robert Alter, who had played with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, substituted for Joseph, Jr. as cellist while the latter served in the army at the end of 1918, when the quartet had scheduled a tour of California. Alter had good chamber music credentials through his association with Alwin Schroeder,[2] cellist for the Kneisel Quartet from 1891 to 1907.[9]

Outside activities

[edit]Unlike their colleagues of the Flonzaley Quartet, who agreed to restrict themselves to performing as a group,[6] various members of the Zoellner Quartet engaged in extensive outside activities. Besides individual undertakings, as noted above the family as a whole opened a music conservatory, eventually with locations in Los Angeles, Hollywood, and Burbank.[3]

Joseph, Jr. for three years was a member of the Symphony Concerts Durand in Brussels,[7] and later served as dean and head of the piano department at the family's conservatory.[5] He also was heard as accompanist for other artists; for instance, he and pianist/composer Charles Gilbert Spross performed with Gina Ciaparelli in the Lyceum at New York's Carnegie Hall on March 5, 1912. On that occasion he played two solos and the obbligato part in Courtlandt Palmer's Lethe.[41]

Joseph, Sr. also was a member of the Durand orchestra. He headed the violin department at the Ecole Communale in Etterbeek, now Brussels, from 1907 to 1912[9] and later the same department at the University of Redlands in Redlands, California. As in Brooklyn and Stockton, he was proprietor of a music school in Brussels.[5]

Amandus taught violin at the Ecole Communale when his father was director there, and like his father and brother he was a member of the Durand orchestra. Also like his father, Amandus served as university violin department director, first at Pomona College in Claremont, California[5] and then at Occidental College in Los Angeles. At the latter he performed solo recitals as well as with the quartet.[34] He helped found the Zoellner Conservatory of Music and eventually served as its president.[13]

Joseph, Sr. and Amandus together compiled The Zoellner Quartette Repertoire Album, a collection of music published by Carl Fischer Music.[13] In addition, Joseph, Sr.; Amandus; and Antoinette all contributed essays regarding quartet playing to an omnibus volume on string instruments.[42]

The New Zoellner Quartet

[edit]Joseph, Jr. followed his father's example by founding a quartet of his own, although it was not made up of relatives. This ensemble was based in Chicago, home town of Joseph, Jr.'s wife;[3] the other members, all with previous connections to artistic organizations in that city, were Charles Buckley and Michael Rill, first and second violinists, respectively, and violist Jose Marones.[7] A family account dated the founding to 1950,[3] but promotional literature cited a review in 1938.[7] In either event, sources agree that the new group was active through the 1950s,[3][4] although it appears not to have achieved its predecessor's level of widespread recognition.

Recordings

[edit]The original Zoellner Quartet left six sides issued as Edison diamond discs[43] and at least three more recorded for Columbia. All were acoustic recordings, and, like their counterparts in the contemporary Flonzaley Quartet's acoustic discography, comprised isolated movements, arrangements, and encore pieces rather than complete works. As noted above, one of the Edison records captured a performance of Skilton's "War Dance," of which the Zoellner Quartet was dedicatee.

- Anonymous: Humoresque on Two American Folk Songs, Columbia 37391; also issued as A-7534 (Nov. 1915)[44]

- Boccherini: Quintet in E, op. 13 no. 5 – Minuet. Edison 80608-R (Nov. 1, 1920)

- Emmett: Dixie. Presumably Columbia (1915)[45]

- Haydn: Quartet in D Major, op. 64 no. 5 ("Lark")—Adagio Cantabile. Edison 80600-L (April 1921)

- Ilyinsky: Orchestral Suite no. 3, op. 13 ("Noure and Anitra")—no. 7, Berceuse. Edison 80692-R (Oct. 13, 1921)

- Ippolitov-Ivanov: String Quartet No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 13—Intermezzo. Edison 80608-L (May 1921)

- MacDowell: Woodland Sketches, op. 51—no. 1, "To a Wild Rose" (arr. Zoellner). Edison 80600-R (Oct. 1, 1920)

- Skilton: Two Indian Dances—no. 2, "War Dance." Edison 80692-L (March 1922)

- Thern: Genius Loci. Columbia 37390; also issued as A-7534 (Nov. 1915)[44]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Probably not early film star Florence Lawrence but rather Florence Lawrence Eldridge, who, according to a March 24, 1951, obituary in the Winona Republican Herald, eventually became the Drama Editor of the Examiner.

- ^ "Zoellner Quartet Celebrating News of the War Declaration", Musical America (April 28, 1917): 45.

- ^ a b c d “Chamber Music Plans,” Musical America, Volume XXVIII, no. 25, October 19, 1918, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Cariaga, Daniel, "Not Taking It with You: A Tale of Two Estates," Los Angeles Times, December 22, 1985, accessed April 2012.

- ^ a b c d University of California, Los Angeles library, performing arts special collections, finding aid for Zoellner Family Collection of Scrapbooks, Photographs, and Papers 1890–1990 Archived December 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Who's Who in Music and Dance in Southern California, Hollywood: Bureau of Musical Research, 1933.

- ^ a b Bell, C.A., “The Flonzaley Quartet,” Gramophone Celebrities no. XXVI, Gramophone, May 1930, accessed May 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Promotional brochure for New Zoellner Quartet, accessed April 2012.

- ^ a b University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa Digital Library, advertisement for Zoellner Quartet from Musical America, August 16, 1919, describing the 1919–1920 season as the quartet's eighth in America, accessed June 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c Remy, Alfred ed., Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Third Edition, New York: G. Schirmer, 1919, accessed June 5, 2012.

- ^ “Five Hundredth Zoellner Concert,” Holly Leaves, Volume VII, no. 32, February 15, 1919, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c The Pacific Coast Music Review, Volume XL, no. 2, April 9, 1921, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c The Pacific Coast Music Review, Volume XLIV no. 1, April 7, 1923.

- ^ a b c d e f Fletcher, Russell Holmes, Who’s Who in California 1942–43, accessed April 2012.

- ^ a b "First Number Citizens Lecture Course Monday, November Fifth,"The Weekly Spectrum Archived 2013-11-10 at the Wayback Machine, North Dakota Agricultural College, Volume XXXVI no. 3, November 7, 1917.

- ^ Scrapbook clipping attributed to Musician, Volume 22, April 1917, page 303[permanent dead link], accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Auction listing by RR Auction, auction closed October 13, 2010.

- ^ a b "Zoellner Quartet Plays: Displays Ability on Its First Appearance Here," The New York Times, January 8, 1914.

- ^ “Sharps and Flats,” Deseret Evening News, Salt Lake City, Utah, October 13, 1917, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ a b “Last Number of Lyceum Course: Zoellner Quartet to Entertain Saturday Evening,” La Crosse Normal Racquet, La Crosse, Wisconsin Normal School, Volume VIII, no. 19, February 28, 1923, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, The Mystic Cat, June 1916, accessed April 2012.

- ^ “Zoellner Quartet Here: Will Play Sixth Concert of University Course April 5,” Lawrence Journal-World, March 29, 1917, accessed April 2012.

- ^ “Zoellner Quartet Concert Will Be Given in Fraser Hall Thursday Evening,” Lawrence Journal-World, April 3, 1917, accessed April 2012.

- ^ Lawrence University Archives Digital Collections, programme for recital by Zoellner Quartet on April 10, 1917, accessed May 31, 2012.

- ^ a b “Zoellners Give Pleasing Concert,”The Weekly Spectrum, North Dakota Agricultural College, Volume XXXVI no. 4, November 7, 1917.

- ^ “Zoellner Quartet Tomorrow,” The Sunday Morning Missourian, Columbia, Missouri, 10th Year, no. 49, November 11, 1917, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Music Teachers' Meeting: Programme of Lecture Recitals at Columbia University," The New York Times, June 23, 1912.

- ^ Marion, Suzanne Davis, Houston Tuesday Musical Club 1911–2011: Journey through a Century of Music, CreateSpace 2011, ISBN 1453857605, accessed April 2012.

- ^ Tuesday Musical Concert Series Archived December 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, past artists listing, accessed April 2012.

- ^ Past artists list Archived December 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine of the Schubert Club.

- ^ Bray, Trevor, Frank Bridge: A Life in Brief, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ Fitzgibbon, H. Macaulay, The Story of the Flute, Teddington, Middlesex: Wildhern Press, 2009, reprint of 1915 ed., ISBN 978-1-84830-180-1, accessed June 3, 2012, a contemporary source, assigns these dates to a composer of this name, but examination of the text reveals that the composer meant was Jean-Baptiste Loeillet of London (1680–1730). Presumably the Zoellner advertisement likewise was referring to the London Loeillet.

- ^ Trapper, Emma L. compiler, The Musical Blue Book of America 1916–1917: Recording in concise form the activities of leading musicians and those actively and prominently identified with music in its various departments, New York: Musical Blue Book Corporation, accessed April 2012.

- ^ Texas Bandmaster Hall of Fame Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine site, sponsored by Alpha Chapter, Phi Beta Mu, accessed April 2012.

- ^ a b Occidental College – La Encina Yearbook (Los Angeles, CA) – Class of 1927 p. 164, accessed April 2012.

- ^ Daily radio listing in Twin Falls Daily News, Twin Falls, Idaho, Volume 10, no. 197, November 24, 1927, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Pisani, Michael V., A Chronological Listing of Musical Works on American Indian Subjects, Composed Since 1608, accessed April 2012. The list is to accompany Michael Pisani, Imagining Native America in Music, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- ^ Stehman, Dan, Roy Harris: A Bio-Bibliography, Bio-Bibliographies in Music no. 40, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1991, ISBN 0-313-25079-0, accessed April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Gates, W. Francis ed., Who's Who in Music in California, "The Pacific Coast Musician," Los Angeles: Colby and Pryibil, 1920.

- ^ Persons born 26 October 1886 in the Social Security Death Master File accessed April 2012.

- ^ "Who's Who and Why," The Violinist, Volume XXIV, no. 2, February 1919, accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Music Here and There," The New York Times, March 3, 1912, accessed April 2012.

- ^ Martins, Frederick, String Mastery, New York: Stokes, 1923.

- ^ All Edison record numbers taken from labels of physical copies; all dates from Wile, Raymond, Edison Diamond Disc Re-Creations: Records & Artists 1910–1929, New York: APM Press, 1985.

- ^ a b Record listing at Joe’s Music Rack, accessed April 2012.

- ^ Marcus, Kenneth, Musical Metropolis: Los Angeles and the Creation of a Music Culture, 1880–1940, Palgrave Macmillan, December 2004, ISBN 978-1-4039-6419-9, accessed April 2012.

External links

[edit]- A photograph of the Zoellner Quartet provided by Musica Viva.

- A photograph of the Zoellner Quartet with autographs of its members.

- A later postcard photograph of the Zoellner Quartet provided by the Claremont Colleges Digital Library.