Zooarchaeology

Zooarchaeology (or archaeozoology) is the branch of archaeology that studies faunal remains related to ancient people.[1] Faunal remains are the items left behind when an animal dies.[1] It includes: bones, shells, hair, chitin, scales, hides, proteins and DNA.[1] Of these items, bones and shells are the ones that occur most frequently at archaeological sites where faunal remains can be found.[1] Most of the time, most of the faunal remains do not survive.[1] They often decompose or break because of various circumstances.[1] This can cause difficulties in identifying the remains and interpreting their significance.[1]

Development

The development of zooarchaeology in Eastern North America can be broken up into three different periods.[2] The first being the Formative period starting around the 1860s, the second being the Systematization period beginning in the early 1950s, and the Integration period which began about 1969.[2] Full-time zooarchaeologists didn’t come about until the Systematization period.[2] Before that it was just a technique that was applied but not specifically studied.

Zooarchaeological specialists started to come about partly because of a new approach to archaeology known as processual archaeology.[3] This approach puts more emphasis on explaining why things happened, not just what happened.[3] Archaeologists began to specialize in zooarchaeology, and their numbers increased from there on.[3]

Uses

Zooarchaeology is primarily used to answer several questions.[3] These include:

- What was the diet like, and in what ways were the animals used for food?[3]

- Which were the animals that were eaten, in what amounts, and with what other foods?[3]

- Who were the ones to obtain the food, and did the availability of that food depend on age or gender?[3]

- How was culture, such as technologies and behavior, influenced by and associated with diet?[3]

- What purposes, other than food, were animals used for?[3]

Zooarchaeology can also tell us what the environment might have been like in order for the different animals to have survived.[3]

In addition to helping us understand the past, zooarchaeology can also help us to improve the present and the future.[4] Studying how people dealt with animals, and its effects can help us avoid many potential ecological problems.[4] This specifically includes problems involving wildlife management.[4] For example, one of the questions that wildlife preservationists ask is whether they should keep animals facing extinction in several smaller areas, or in one larger area.[4] Based on zooarchaeological evidence, they found that animals that are split up into several smaller areas are more likely to go extinct.[4]

Techniques

One of the techniques that zooarchaeologists use is close attention to taphonomy.[2] This includes studying how items are buried and deposited at the site in question, what the conditions are that aid in the preservation of these items, and how these items get destroyed.[2] Then they interpret that information.[2]

Another technique that zooarchaeologists use is lab analysis.[2] This analysis can include comparing the skeletons found on site with already identified animal skeletons.[2] This not only helps to identify what the animal is, but also whether the animal was domesticated or not.[2]

Yet another technique that zooarchaeologists use is quantification.[2] They make interpretations based on the number and size of the bones.[2] These interpretations include how important different animals might have been to the diet.[2]

Limitation of techniques

There are limitations to using excavation techniques in studying different kinds of faunal remains. It is difficult to screen or sieve large animals remains, and thus it is hard to recover larger animals and bone fragments. Second, it is hard to collect the remains of all animals species, potentially creating biased and unrepresentative data collection. Third, it is difficult to distinguish the original use and reuse of the land, since different activities can be represented in the same area at different times.[5]

Related fields

As can be seen from the discussion about the name that should be given to this discipline, zooarchaeology overlaps significantly with other areas of study. These include:

- Anthropology

- Anthrozoology

- Archaeology

- Biology

- Ecology

- Ethnography

- Paleopathology

- Palaeontology

- Paleozoology

- Zoology

Wider areas of study

Such analyses provide the basis by which further interpretations can be made. Topics that have been addressed by zooarchaeologists include:

|

|

Prehistory

Human-Animal relationships and interactions were diverse during Prehistory from being a food source to playing a more intimate role in society.[6] Animals have been used in non-economical ways such as being part of a human burial. However, the major zooarchaeology has focused on who was eating what by looking at various remains such as bones, teeth, and fish scales.[6] In the twenty-first century researchers have begun to interpret animals in prehistory in wider cultural and social patterns, focusing on how the animals have affected humans and possible animal agency.[6] There is evidence of animals such as the Mountain Lion or the Jaguar being used for ritualistic purposes, but not being eaten as a food source.[6]

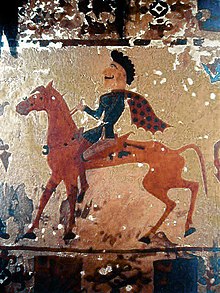

Animal burials date back to prehistory with examples emerging from the Mesolithic period. In Sweden at the burial site Skateholm I dogs were found buried with children under eight years old or were found buried by themselves. Some of the dogs who were buried alone have grave goods similar to their human contemporaries such as flint weapons and deer antlers.[6] Meanwhile, during the same time period Skateholm II emerged and was very different than Skateholm I, as dogs were buried along on the North and West boundaries of the grave area.[6] Another burial site in Siberia near Lake Biakal known as the "Lokomotiv" cemetery had a wolf burial among human graves.[6][7] Buried together with, but slightly beneath the wolf was a male human skull.[7] The wolf breed was not native to this area as it was warm and other research for the area shows no other wolf habitation.[7] Bazaliiskiy & Savelyev suggests that the presence and significance of the wolf could possibly reflect human interaction.[7] Another example occurred in 300 B.C. in Pazyryk known as the Pazyryk burials where ten horses were buried alongside a human male, the horses were fully adorned with saddles, pendants, among other valuables.[6] The oldest horse as also the horse with the grandest attachments. Erica Hill, a professor in archaeology, suggests that the burials of prehistory animals can shed light on human-animal relationships.[6]

Significance

Zooarchaeology allows researchers to have a more holistic understanding of past human-environment interactions. Whether it is diet, domestication, tool use, or ritual; animal remains reveal so much about the groups that interacted with them. Archaeology provides information on the past which often proves invaluable for understanding the present and preparing for the future.[8] Zooarchaeology plays a valuable part in contributing to a holistic understanding of the animals themselves, the nearby groups, and the local environments.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Yohe II, Robert M. (2006). Archaeology: The Science of the Human Past. Pearson. pp. 248–264.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Landon, David B. (2005). "Zooarchaeology and Historical Archaeology: Progress and Prospects". Journal of Archaeological Method and. 12 (1).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Thomas, Kenneth D. (1996). "Zooarchaeology: Past, Present and Future". World Archaeology. 28 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1080/00438243.1996.9980327. PMID 16475284.

- ^ a b c d e Lyman, R. L. (1996). "Applied Zooarchaeology: The Relevance of Faunal Analysis to Wildlife Management". World Archaeology. 28: 110–125. doi:10.1080/00438243.1996.9980334.

- ^ Woollett, James M. (1 January 1999). "Living in the Narrows: Subsistence Economy and Culture Change in Labrador Inuit Society during the Contact Period". World Archaeology. 30 (3): 370–387. doi:10.1080/00438243.1999.9980418. JSTOR 124958.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hill, Erica (2013). "Archaeology and Animal Persons: Toward a Prehistory of Human-Animal Relations". Environment and Society. 4 (1). doi:10.3167/ares.2013.040108.

- ^ a b c d Bazaliiskiy & Savelyev (2003). "The Wolf of Baikal: The "Lokomotiv" Early Neolithic Cemetery in Siberia (Russia)". Antiquity. 77 (295).

- ^ O'Connor, Terence P. 2013. The archaeology of animal bones. Stroud: History Press.

Bibliography

- Orton, David C. "Anthropological Approaches to Zooarchaeology: Colonialism, Complexity and Animal Transformations." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21.2 (2011): 323-24. Print.

External links

- Association of Environmental Archaeology

- BoneCommons(ICAZ)

- International Council for Archaeozoology(ICAZ)

- Archeozoo: collaborative website of archaeozoology

- ArchéoZooThèque : images bank in archaeozoology proposed by the website ArchéoZoo.org[permanent dead link]

- OpenContext.org (Zooarchaeology data) Multiple zooarchaeological datasets and media published in Open Context.

- Acosta et al., 2018. Climate change and peopling of the Neotropics during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. http://boletinsgm.igeolcu.unam.mx/bsgm/index.php/component/content/article/368-sitio/articulos/cuarta-epoca/7001/1857-7001-1-acosta