Blue runner

| Blue runner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Carangiformes |

| Family: | Carangidae |

| Genus: | Caranx |

| Species: | C. crysos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Caranx crysos (Mitchill, 1815)

| |

| |

| Approximate range of the blue runner | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The blue runner (Caranx crysos), also known as the bluestripe jack, Egyptian scad, hardtail jack or hardnose, is a common species of moderately large marine fish classified in the jack family, Carangidae. The blue runner is distributed across the Atlantic Ocean, ranging from Brazil to Canada in the western Atlantic and from Angola to Great Britain including the Mediterranean in the east Atlantic. The blue runner is distinguished from similar species by several morphological features, including the extent of the upper jaw, gill raker count and lateral line scale counts. The blue runner is known to reach a maximum length of 70 cm and 5.05 kg in weight, but is much more common below 35 cm. The species inhabits both inshore and offshore environments, predominantly over reefs, however it is known to congregate around large, man-made, offshore structures such as oil platforms. Juveniles tend to inhabit shallower reef and lagoon waters, before moving to deeper waters as adults.

The blue runner is a schooling, predatory fish, predominantly taking fish in inshore environments, as well as various crustaceans and other invertebrates. Fish living offshore feed nearly exclusively on zooplankton. The species reaches sexual maturity at between 225 and 280 mm across its range, with spawning occurring offshore year round, although this peaks during the warmer months. Larvae and juveniles live pelagically, often under sargassum mats or jellyfish until they move inshore. The blue runner is of high importance to fisheries, with an annual catch of between 6000 and 7000 tonnes taken from the Americas in the last five years. The species is also a light tackle gamefish, taking baits, lures, and flies; but is often used as bait itself, being a mediocre table fish. There has been some suggestion that the eastern Pacific species Caranx caballus, the green jack, may be conspecific with C. crysos, although this currently remains unresolved.

Taxonomy and naming

[edit]The blue runner is classified within the genus Caranx, one of a number of groups known as the jacks or trevallies. Caranx itself is part of the larger jack and horse mackerel family Carangidae, part of the order Carangiformes.[2]

The species was first scientifically described by the American ichthyologist Samuel L. Mitchill in 1815, based on a specimen taken from the waters of New York Bay, USA which was designated to be the holotype.[3] He named the species Scomber crysos and suggested a common name of 'yellow mackerel', with the specific epithet reflecting this, meaning "gold" in Greek.[3] The taxon has been variably placed in either Caranx, Carangoides or Paratractus, but is now considered valid as Caranx crysos.[4] The species has been independently redescribed three times, first as Caranx fusus, which is still incorrectly used by some authors[5] (occasionally as Carangoides fusus), and later as Caranx pisquetus and Trachurus squamosus. These names are considered invalid junior synonyms under ICZN rules. The species has many common names, with the most common being 'blue runner'. Other less commonly used names include 'bluestripe jack', 'Egyptian scad', 'hardtail jack', 'hardnose', 'white back cavalli', 'yellow tail cavalli', as well as a variety of broad names such as 'mackerel', 'runner' and 'crevalle'.[4][6]

There have been suggestions that the blue runner may be conspecific with the eastern Pacific species Caranx caballus (green jack), although no specific studies have been undertaken to examine this relationship.[7][8] Both species were included in a recent genetic analysis of the entire family Carangidae, with results showing both species are very closely related, although the authors did not comment on genetic distance between the two.[9]

Description

[edit]

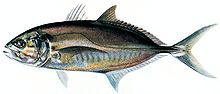

The blue runner is moderately large in size, growing to a maximum confirmed length of 70 cm and 5.05 kg in mass, but is more common at lengths less than 35 cm.[4] The blue runner is morphologically similar to a number of other carangids, having an elongated, moderately compressed body with dorsal and ventral profiles of approximately equal convexity and a slightly pointed snout.[10] The posterior section of the eye is covered by a moderately well developed adipose eyelid, and the posterior extremity of the jaw is vertically under the center of the eye.[11] The dorsal fin is in two parts, the first consisting of 8 spines and the second of 1 spine followed by 22 to 25 soft rays. The anal fin consists of 2 anteriorly detached spines followed by 1 spine and 19 to 21 soft rays.[10] The pectoral fins become more falcate with age,[7] having 21 to 23 rays, and are slightly longer than the head.[12] The lateral line has a pronounced but short anterior arch, with the curved section intersecting the straight section below the spine of the second dorsal fin. The straight section contains 0 to 7 scales followed by 46 to 56 very strong scutes, with bilateral keels present on the caudal peduncle. There are a total of 86 to 98 scales and scutes over the entire lateral line.[13] The chest is completely scaled. The upper jaw contains an irregular series of outer canines with an inner band of small, regularly spaced teeth, while the lower jaw contains a single band of small teeth.[11] The species has 35 to 42 gill rakers in total; 10 to 14 on the upper limb and 25 to 28 on the lower limb, with this the only feature that differs between C. crysos and C. caballus. There are 25 vertebrae present.[10]

The blue runner's colour varies from bluish green to olive green dorsally, becoming silvery grey to brassy below. Juveniles often have 7 dark vertical bands on their body. Fin colour also varies, with all fins ranging from to dusky or hyaline to olive green. The species also has a dusky spot which may not be distinct on the upper operculum.[11][12]

Distribution

[edit]The blue runner is extensively distributed throughout the tropical and temperate waters of the Atlantic Ocean, ranging widely along both the eastern American coastline and the western African and European coastlines.[4] In the western Atlantic, the species southernmost record comes from Maceio, Brazil,[10] with the species ranging north along the Central American coastline, and throughout the Caribbean and the numerous archipelagos throughout.[12] From the Gulf of Mexico its distribution extends north along the U.S. coast and as far north as Nova Scotia in Canada, also taking in several north-west Atlantic islands.[4] The blue runner is also present on several central Atlantic islands, making its distribution Atlantic-wide.[citation needed]

In the eastern Atlantic the southernmost record is from Angola, with the blue runner distributed extensively along the west African coast up to Morocco and into the Mediterranean Sea.[11] The blue runner is found throughout the Mediterranean, having been recorded from nearly all the countries on its shores.[4] The species is rarely found north of Portugal in the north east Atlantic, although records do exist of isolated catches from Madeira Island[14] and Galicia, Spain.[15] The furthest north it has been reported is southern Great Britain, where two specimens were taken in 1992 and 1993.[16] There has been a trend of having this and other tropical species found further north more often, with publications indicating the blue runner has recently established stable populations in the Canary Islands, where it had been rarely sighted. Some authors have attributed this northward migration to rising sea surface temperatures, possibly the result of climate change.[17]

Habitat

[edit]

The blue runner is primarily an inshore fish throughout most of its range, however it is known to live on reefs in water depths greater than 100 m.[11] Throughout much of its Central American range, it is quite rare inshore, instead more commonly sighted on the outer reefs.[10] The blue runner is primarily a semi-pelagic fish, inhabiting both inshore reefs and the outer shelf edges, sill reefs and upper slopes of the deep reef.[5] Those individuals on shallower reefs often move between reef patches over large sand expanses. Juvenile fish are also known to inhabit the shallow waters of inshore lagoons, taking refuge around mangroves[10] or in seagrass amongst coral reef patches.[18] Fishermen have also taken the species in the Mississippi delta, indicating it can tolerate lower salinities in almost estuarine environments.[19]

Blue runner are easily attracted to any large underwater or floating device, either natural or man made. Several studies have shown the species congregates around floating buoy-like fish aggregating devices (FADs), both in shallower waters, as well as in extremely deep (2500 m) waters, indicating the species may move around pelagically.[20] In these situations, blue runner always form small aggregations at the water surface, while other larger species tend to congregate slightly deeper.[20] A number of investigations around oil and gas platforms in the Gulf of Mexico have found blue runner congregate in large numbers around these in the warmer months, where they modify their feeding behavior to take advantage of the structure.[21] Purpose-built artificial reefs[22] and marine aquaculture cage structures are also known to attract the species, with the former having the added benefit of dispersing wayward food scraps.[23]

Biology

[edit]The blue runner normally moves either in small schools or as solitary individuals,[10] although large aggregations of up to 10,000 individuals are known in unusual circumstances.[21] Throughout some parts of its range, it is one of the most abundant species; for example statistics from Santa Catarina Island indicate it is the third most abundant species.[24] The biology, particularly reproductive and growth biology has been quite extensively studied in the blue runner due to this high abundance in the Atlantic, and its importance to fisheries and the ecology of its environment.[citation needed]

Diet and feeding

[edit]The blue runner is a fast-swimming predator which primarily takes small benthic fishes as prey in inshore waters.[10] Studies on the species diet on both side of the Atlantic have shown similar results. A Puerto Rican study found the species supplements its fish dominated diet with crabs, shrimps, copepods and other small crustaceans.[25] More detailed research in Cape Verde found as well as fish, blue runner take shrimp, prawns, lobsters, jellyfish and other small invertebrates.[26] The diet of juveniles is more zooplankton dominated, with young fish predominantly taking cyclopoid and calanoid copepods, and gradually moving to a more fish based diet.[27] Adult blue runner living offshore or aggregating around oil and gas platforms tend to have less fish in their diet, foraging extensively on larger zooplankton during the summer months, with larval decapods and stomatopods, hyperiid amphipods, pteropods, and larval and juvenile fishes also taken.[28]

Studies around these platforms has found blue runner feed with equal intensity during both day and night, with larger prey such as fish taken preferentially at night, with smaller crustaceans taken during the day.[28] Blue runner are one of a number of carangids known to forage in small schools alongside actively feeding spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris), taking advantage of any scraps of food left by the feeding mammals, or any organisms displaced while they forage.[29] The species is also known to eat the dolphins excrement.[29] As well as being important predators, they are also important prey to many larger species including fishes, birds and dolphins.[4][30]

Reproduction and growth

[edit]

The blue runner reaches sexual maturity at slightly different lengths throughout its range, with all such studies occurring in the west Atlantic. Research in northwest Florida found a length at maturity of 267 mm,[31] a study in Louisiana showed the species reaches sexual maturity at 247–267 mm in females and 225 mm in males, and in Jamaica lengths of 260 mm for males and 280 for females were estimated.[32] Spawning appears to occur offshore year round, although several peaks in spawning activity have been found in different areas through the species range. Peak spawning season in the Gulf of Mexico occurs from June to August, with a secondary peak in spawning during October in northwest Florida.[31] Elsewhere, peaks in larval abundance indicate spawning in the warmer summer months between January and August.[32] Each female releases between 41,000 and 1,546,000 eggs on average, with larger fish producing more eggs.[31] Both the eggs and larvae are pelagic.[33]

The blue runner's larval stage has been extensively described, with distinguishing features including a slightly shallower body than other larval Caranx, and a heavily pigmented head and body.[34] During this early juvenile stage, there are several dark vertical bars clearly present on the side.[34] Larvae and small juveniles remain offshore, living either at depths of around 10 to 20 m,[32] or congregating around floating objects, particularly Sargassum mats and large jellyfish.[35] As the fish grow, they often move to more inshore lagoons and reefs, before slowly making their way to deeper outer reefs at the onset of sexual maturity.[5] Absolute growth rates are not well known, but the species has all the adult characteristics by a length of 59.3 mm.[36] In all cases studied, there are more females in the adult population than males, with female to male ratios ranging from 1.15F:1M to 1.91F:1M.[31] Annual mortality rates for the population in the Gulf of Mexico range from 0.41 to 0.53. The oldest known individual was 11 years old based on otolith rings.[19]

Relationship to humans

[edit]The blue runner is a highly important species to commercial fisheries throughout parts of its range. Due to its abundance, it may be one of the primary species in a fishery. The availability of fisheries statistics for the species is variable throughout its range, with the Americas having separate statistics kept for the species, while in Africa and Europe it is lumped in with other carangids in statistics.[37] In the Americas, recent catch data suggests an increased amount of the species is being taken (or reported), with the 2006 and 2007 catch averaging between 6000 and 7000 tonnes, while during the 1980s and 1990s, there was rarely an annual catch greater than 1000 tonnes.[37] Research on the fisheries of local regions has shown how important the fish is to certain fisheries. Artisanal fisheries in Santa Catarina Island have shown blue runner to be third most important and abundant species, making up 5.6% of landings, or 4.38 tonnes.[24] Even subsistence fisheries at the edge of its range in Brazil show a catch of 388 kg in two years from beach seines.[38] Throughout its range the blue runner is commercially taken by haul seines, lampara nets, purse seines, gill nets, and hook and line methods.[10] The fish is sold at market either fresh, dried, smoked or as fishmeal, oil or bait.[11]

Blue runner is also of high importance to recreational fisheries, with anglers often taking the species both for food and to use as bait. The blue runner has a reputation as an excellent gamefish on light tackle, taking both fish baits, as well a variety of lures including hard-bodied bibbed lures, spoons, metal jigs and soft plastic jigs.[39] The species is also a target for light tackle saltwater fly fishermen, and can push 6-weight fly tackle to its limits.[40] The IGFA world record for Blue Runner stands at 5.05 kg (11 lbs 2 oz) caught off Dauphin Island by Stacey Moiren in 1997,[41] previous records have also come from the eastern North Atlantic.[42] The blue runner is used extensively as live bait for larger fish, including billfish, cobia and amberjack. It is considered a fairly low-quality table fish,[10] and larger specimens are known to carry the ciguatera toxin in their flesh, with several cases reported from the Virgin Islands.[43]

References

[edit]- ^ Herdson, D. (2010). "Caranx crysos". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T154807A4637970. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T154807A4637970.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. pp. 380–387. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ a b Mitchill, S.L. (1815). "The fishes of New York described and arranged". Transactions of the Literary and Philosophical Society of New York. 1. Van Winkle and Wiley: 355–492.

- ^ a b c d e f g Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Caranx crysos". FishBase. May 2009 version.

- ^ a b c Munro, J. L. (1983) [1974]. "The Biology, Ecology and Bionomics of the Jacks, Carangidae". Caribbean Coral Reef Fishery Resources (A second edition of The biology, ecology, exploitation, and management of Caribbean reef fishes : scientific report of the ODA/UWI Fisheries Ecology Research Project, 1969-1973, University of the West Indies, Jamaica.). Manila: International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management. pp. 82–94. ISBN 971-10-2201-X.

- ^ Jennings, G.H. (1999). Sea fishes of the Caribbean Sea & Gulf of Mexico: Guyana to Florida: a classified taxonomic checklist of recorded species from the West Central Atlantic area. Calypso Publications. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-906301-88-3.

- ^ a b Nichols, J.T. (1920). "On Caranx crysos, Etc". Copeia. 81 (81). American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists: 29–30. doi:10.2307/1435929. JSTOR 1435930.

- ^ Fischer, W.; Krupp F.; Schneider W.; Sommer C.; Carpenter K.E.; Niem V.H. (1995). Guía FAO para la identificación de especies para los fines de la pesca. Pacífico centro-oriental. Volumen II. Vertebrados – Parte 1. Rome: FAO. p. 953. ISBN 92-5-303409-2.

- ^ Reed, David L.; Carpenter, Kent E.; deGravelle, Martin J. (2002). "Molecular systematics of the Jacks (Perciformes: Carangidae) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences using parsimony, likelihood, and Bayesian approaches". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 23 (3): 513–524. Bibcode:2002MolPE..23..513R. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00036-2. PMID 12099802.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Carpenter, K.E., ed. (2002). The living marine resources of the Western Central Atlantic. Volume 3: Bony fishes part 2 (Opistognathidae to Molidae), sea turtles and marine mammals (PDF). FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes and American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Special Publication No. 5. Rome: FAO. p. 1438. ISBN 92-5-104827-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Fischer, W; Bianchi, G.; Scott, W.B. (1981). FAO Species Identification Sheets for Fishery Purposes: Eastern Central Atlantic Vol 1. Ottawa: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ a b c McEachran, J.D.; J.D. Fechhelm (2005). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Scorpaeniformes to tetraodontiformes. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 1014. ISBN 978-0-292-70634-7.

- ^ Berry, F.H. (1960). "Scale and scute development of the carangid fish Caranx crysos (Mitchill)". Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences. 23: 59–66.

- ^ Wirtz, P.; R. Fricke; M.J. Biscoito (2008). "The coastal fishes of Madeira Island – new records and an annotated check-list". Zootaxa. 1715: 1–26. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1715.1.1. ISSN 1175-5326.

- ^ Banon Diaz, R.; J.M. Casas Sanchez (1998). "First record of Caranx crysos (Mitchill, 1815), in Galician waters". Boletin del Instituto Espanol de Oceanografia. 31 (1–2): 79–81. ISSN 0074-0195.

- ^ Swaby, S.E.; G.W. Potts; J. Lees (1996). "The first records of the blue runner Caranx crysos (Pisces: Carangidae) in British waters". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 76 (2): 543–544. Bibcode:1996JMBUK..76..543S. doi:10.1017/S0025315400030745. ISSN 0025-3154. S2CID 84294903.

- ^ Brito, A.; J.M. Falcon; R. Herrera (2005). "Sobre la tropicalizacion reciente de la ictiofauna litoral de las islas Canarias y su relacion con cambios ambientales y actividades antropicas". Vieraea. 33: 515–525. ISSN 0210-945X.

- ^ Alvarez-Guillen, H.; M.L.C. Garcia-Abad; M. Tapia Garcia; G.J. Villalobos Zapata; A. Yanez-Arancibia (1986). "Ichthyoecological survey in the sea grass zone of the reef lagoon of Puerto Morelos Quintana Roo Mexico Summer 1984". Anales del Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnologia Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. 13 (3): 317–336. ISSN 0185-3287.

- ^ a b Goodwin, J.M.; A.G. Johnson (1986). "Age growth and mortality of blue runner Caranx crysos from the northern Gulf of Mexico". Northeast Gulf Science. 8 (2): 107–114. doi:10.18785/negs.0802.02. ISSN 0148-9836.

- ^ a b Doray, M.; E. Josse; P. Gervain; L. Reynal; J. Chantrel (2007). "Joint use of echosounding, fishing and video techniques to assess the structure of fish aggregations around moored Fish Aggregating Devices in Martinique (Lesser Antilles)". Aquatic Living Resources. 20 (4): 357–366. doi:10.1051/alr:2008004. S2CID 17177578.

- ^ a b Stanley, D.R.; B.A. Scarborough (2003). "Seasonal and spatial variation in the biomass and size frequency distribution of fish associated with oil and gas platforms in the northern Gulf of Mexico". Fisheries, Reefs, and Offshore Development. 36: 123–153. ISSN 0892-2284.

- ^ Brotto, D.S.; W. Krohling; S. Brum; I.R. Zalmon (2006). "Usage patterns of an artificial reef by the fish community on the northern coast of Rio de Janeiro – Brazil". Journal of Coastal Research. 3 (Special Issue 39): 1276–1280. ISSN 0749-0208.

- ^ Vega Fernandez, T.; G. D'Anna; F. Badalamenti; C. Pipitone; M. Coppola; G. Rivas; A. Modica (2003). "Fish fauna associated to an off-shore aquaculture system in the Gulf of Castellammare (NW Sicily)". Biologia Marina Mediterranea. 10 (2 (Supp.)): 755–759. ISSN 1123-4245.

- ^ a b Martins, R.S.; M.J.A. Perez (2008). "Artisanal Fish-Trap Fishery Around Santa Catarina Island During Spring/Summer: Characteristics, Species Interactions and the Influence of the Winds on the Catches" (PDF). Boletim do Instituto de Pesca. 34 (3): 413–423. Retrieved 22 May 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Randall, J.E. (1967). "Food habits of reef fishes of the West Indies". Studies in Tropical Oceanography. 5: 665–847. ISSN 0081-8720.

- ^ da Silva Monteiro, V.M. (1998). Peixes de Cabo Verde. Lisbon: Ministério do Mar, Gabinete do Secretário de Estado da Cultura. M2- Artes Gráficas, Lda. p. 179.

- ^ Mirto, S.; M. Bellavia; T. La Rosa (2002). "Primi dati sulle abitudini alimentari di giovanili di Caranx crysos nel Golfo di Castellammare (Sicilia nord occidentale)". Biologia Marina Mediterranea. 9 (1 (Supp.)): 726–728. ISSN 1123-4245.

- ^ a b Keenan, S.F.; M.C. Benfield (2003). Importance of zooplankton in the diets of Blue Runner (Caranx crysos) near offshore petroleum platforms in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. OCS Study MMS 2003-029. New Orleans: Coastal Fisheries Institute, Louisiana State University. U.S. Dept. of the Interior. p. 129.

- ^ a b Sazima, I.; C. Sazima; J.M. da Silva (2006). "Fishes associated with spinner dolphins at Fernando de Noronha Archipelago, tropical Western Atlantic: an update and overview" (PDF). Neotropical Ichthyology. 4 (4): 451–455. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252006000400009.

- ^ Beltran-Pedrerosde, S.; T.M. Araujo Pantoja (2006). "Feeding habits of Sotalia fluviatilis in the amazonian estuary". Acta Scientiarum Biological Sciences. 28 (4): 389–393. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d Goodwin, J.M.; J.H. Finucane (1985). "Reproductive biology of blue runner Caranx crysos from the eastern Gulf of Mexico". Northeast Gulf Science. 7 (2): 139–146. doi:10.18785/negs.0702.02. ISSN 0148-9836.

- ^ a b c Shaw, R.F.; D.L. Drullinger (1990). "Early-Life-History Profiles, Seasonal Abundance, and Distribution of Four Species of Carangid Larvae off Louisiana, 1982 and 1983". NOAA Technical Report NMFS. 89. US Department of Commerce: 1–44.

- ^ Samira, S.S (1999). "Reproductive biology, spermatogenesis and ultrastructure of testes Caranx crysos (Mitchill, 1815)". Bulletin of the National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries. 25: 311–329. ISSN 1110-0354.

- ^ a b Richards, William J. (2006). Early Stages of Atlantic Fishes: An Identification Guide for the Western Central North Atlantic. CRC Press. pp. 2640 pp. ISBN 978-0-8493-1916-7.

- ^ Wells, R.J.D.; J.R. Rooker (2004). "Spatial and temporal patterns of habitat use by fishes associated with Sargassum mats in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico" (PDF). Bulletin of Marine Science. 74 (1): 81–99. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Assem, S.S. (2000). "The reproductive biology and histological characteristics of pelagic carangid female Caranx crysos from the Egyptian Mediterranean Sea". Journal of the Egyptian German Society of Zoology. 31 (C): 195–215. ISSN 1110-5348.

- ^ a b Fisheries and Agricultural Organisation. "Global Production Statistics 1950–2007". Blue runner. FAO. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^ Tubino, R.D.; C. Monteiro; L.E.D. Moraes; E.T. Paes (2007). "Artisanal fisheries production in the coastal zone of Itaipu, Niteroi, RJ, Brazil" (PDF). Brazilian Journal of Oceanography. 55 (3): 187–197. doi:10.1590/s1679-87592007000300003.

- ^ Ristori, Al (2002). Complete Guide to Saltwater Fishing. Woods N' Water, Inc. p. 59. ISBN 0-9707493-5-X.

- ^ Thomas Jr., E. Donnall; E. Donnall Thomas (2007). Redfish, Bluefish, Sheefish, Snook: Far-Flung Tales of Fly-Fishing Adventure. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-60239-119-2.

- ^ "Record Details". igfa.org. International Game Fish Association.

- ^ "Record History". igfa.org. International Game Fish Association. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Morris, J.G.; P. Lewin; C.W. Smith; P.A. Blake; R. Schneider (1982). "Ciguatera Fish Poisoning – Epidemiology of the Disease on St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 31 (3): 574–578. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.574. ISSN 0002-9637. PMID 7200733.

External links

[edit]- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at FishBase

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at Gulf of Maine Research Institute

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at Indian River

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine at Fishing-boating.com Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at Combat Fishing

- Photos of Blue runner on Sealife Collection