Self-expandable metallic stent

| Self-expandable metallic stent | |

|---|---|

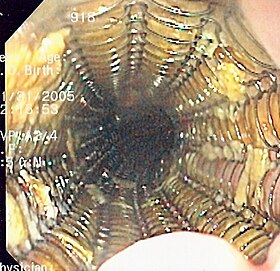

Endoscopic view of a self-expandable metallic stent used to palliate an esophageal cancer | |

| Other names | SEMS |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

A self-expandable metallic stent (or SEMS) is a metallic tube, or stent that holds open a structure in the gastrointestinal tract to allow the passage of food, chyme, stool, or other secretions related to digestion. Surgeons insert SEMS by endoscopy, inserting a fibre optic camera—either through the mouth or colon—to reach an area of narrowing. As such, it is termed an endoprosthesis. SEMS can also be inserted using fluoroscopy where the surgeon uses an X-ray image to guide insertion, or as an adjunct to endoscopy.

The vast majority of SEMS are used to alleviate symptoms caused by cancers of the gastrointestinal tract that obstruct the interior of the tube-like (or luminal) structures of the bowel — namely the esophagus, duodenum, common bile duct and colon. SEMS are designed to be permanent and, as a result, are often used when the cancer is at an advanced stage and cannot be removed by surgery.

Composition and structure

[edit]

Self-expandable metallic stents are cylindrical in shape, and are devised in a number of diameters and lengths to suit the application in question.[1] They typically consist of cross-hatched, braided or interconnecting rows of metal that are assembled into a tube-like structure. SEMS, when unexpanded, are small enough to fit through the channel of an endoscope, which is meant for delivery of devices for therapeutic endoscopy. They expand through a deployment device placed at the end of the SEMS, and are held in place against the wall of the luminal surface by friction.[2]

SEMS may be coated with chemicals designed to prevent tumour ingrowth; these are termed "covered" stents. Nitinol[3] (a shape memory nickel-titanium alloy), polyurethane,[4] and polyethylene[5] are typically used as coatings for SEMS. Covered stents carry the advantage of preventing tumours from growing into the stent, although they run the risk of increased migration after deployment.[6]

A plastic self-expanding stent (Polyflex, Boston Scientific) has also been developed for similar applications. It confers an additional advantage as it is designed to be removable, and may have a less traumatic insertion than metal stents. The Polyflex stent has shown benefit in palliation of esophageal malignancies.[7]

Applications

[edit]The primary application of SEMS is in the palliation of tumours that obstruct the gastrointestinal tract. When they expand within the lumen, they are able to hold open the structure and allow passage of material, such as food, stool, or other secretions. The usual applications are for cancers of the esophagus, pancreas, bile ducts and colon that are not amenable to surgical therapy. SEMS are used to treat additional complications of cancer, such as tracheoesophageal fistulas from esophageal cancer,[8] and gastric outlet obstruction from stomach, duodenal, or pancreatic cancer.[9]

SEMS and self-expanding plastic stents have also been used for non-malignant conditions that cause narrowing or leaks of the esophagus or colon. These include peptic strictures caused by esophageal reflux[10] and perforations of the esophagus.[11] SEMS may also be placed in tandem fashion to treat ingrowth or overgrowth tumours, and fractures or migration of other SEMS. For the latter, the second SEMS in usually deployed within the lumen of the first.[12]

SEMS are also sometimes used in the vascular system, usually in the aorta and peripheral vascular system. In the past they have been used for saphenous vein graft and native coronary artery percutaneous coronary interventions.[citation needed]

Deployment

[edit]

Self-expandable metallic stents are typically inserted at the time of endoscopy, usually with assistance with fluoroscopy or x-ray images taken to guide placement. Prior to the development of SEMS small enough to pass through the channel of the endoscopy, SEMS were deployed using fluoroscopy alone.[13]

Esophageal SEMS are placed after a gastroscopy is performed to identify the area of narrowing. The area may need to be dilated to allow the gastroscope to pass.[14] The tumour is usually better seen with the direct vision of endoscopy than on a fluoroscopic image. As a result, radio-opaque markers are usually placed on the surface of the patient to mark the area of narrowing on fluoroscopy. The SEMS is placed through the channel of the endoscope into the esophagus over a guidewire, marked on fluoroscopy, and mechanically deployed (using a device that sits outside of the endoscope) such that it expands when in position. Hypaque or other water-soluble dye may be placed through the passage to ensure patency of the stent on fluoroscopy.[15] Enteric and colonic SEMS are inserted in a similar fashion, but in the duodenum and colon respectively.[16]

Biliary SEMS are used to palliatively treat tumours of the pancreas or bile duct that obstruct the common bile duct. They are inserted at the time of ERCP, a procedure that uses endoscopy and fluoroscopy to access the common bile duct. The bile duct is cannulated with the assistance of a guidewire and the sphincter of Oddi that is located at its base is typically cut. A wire is kept in the bile duct, and the SEMS is deployed over the wire in a similar fashion as esophageal stents. The location of the SEMS is confirmed by fluoroscopy.[17]

Complications

[edit]

The complications of SEMS are related to a number of factors. The first is that the endoscopic procedure used to insert a SEMS involves the use of sedative medications, which may lead to oversedation, aspiration, or drug reaction. SEMS also expand and can lead to perforation of the bowel or compression of structures adjacent to the bowel.[18]

Long-term complications of SEMS may be related to the underlying tumour being treated: the tumour may grow into the stent wall (tumour ingrowth) or over the end of the stent (tumour overgrowth), leading to obstruction. These complications may be limited by the use of coated stents.[6][19] Tumour ingrowth or overgrowth can be additionally palliated by the placement of a second stent through the lumen of the first,[6] through electrocautery or argon plasma coagulation of the tumour tissue in the stent,[6] or through the use of photodynamic therapy.[20]

Over time, SEMS may also migrate to a different position that does not help with treatment of the obstructed area.[6] This may be treated with placement of a second SEMS, or endoscopic attempts to reposition or remove the first.[21] Rarely, SEMS may fracture[12] or intussescept after endoscopic intervention.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ Vitale G, Davis B, Tran T (2005). "The advancing art and science of endoscopy". Am J Surg. 190 (2): 228–33. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.05.017. PMID 16023436.

- ^ Mauro M, Koehler R, Baron T (2000). "Advances in gastrointestinal intervention: the treatment of gastroduodenal and colorectal obstructions with metallic stents". Radiology. 215 (3): 659–69. doi:10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn30659. PMID 10831681.

- ^ Schmassmann A, Meyenberger C, Knuchel J, Binek J, Lammer F, Kleiner B, Hürlimann S, Inauen W, Hammer B, Scheurer U, Halter F (1997). "Self-expanding metal stents in malignant esophageal obstruction: a comparison between two stent types". Am J Gastroenterol. 92 (3): 400–6. PMID 9068458.

- ^ Song H, Park S, Jung H, Kim S, Kim J, Huh S, Kim T, Kim Y, Park S, Yoon H, Sung K, Min Y (1997). "Benign and malignant esophageal strictures: treatment with a polyurethane-covered retrievable expandable metallic stent". Radiology. 203 (3): 747–52. doi:10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169699. PMID 9169699.

- ^ Saxon R, Morrison K, Lakin P, Petersen B, Barton R, Katon R, Keller F (1997). "Malignant esophageal obstruction and esophagorespiratory fistula: palliation with a polyethylene-covered Z-stent". Radiology. 202 (2): 349–54. doi:10.1148/radiology.202.2.9015055. PMID 9015055.

- ^ a b c d e Ell C, Hochberger J, May A, Fleig W, Hahn E (1994). "Coated and uncoated self-expanding metal stents for malignant stenosis in the upper GI tract: preliminary clinical experiences with Wallstents". Am J Gastroenterol. 89 (9): 1496–500. PMID 7521573.

- ^ Decker P, Lippler J, Decker D, Hirner A (2001). "Use of the Polyflex stent in the palliative therapy of esophageal carcinoma: results in 14 cases and review of the literature". Surg Endosc. 15 (12): 1444–7. doi:10.1007/s004640090099. PMID 11965462.

- ^ Nelson D, Silvis S, Ansel H (1994). "Management of a tracheoesophageal fistula with a silicone-covered self-expanding metal stent". Gastrointest Endosc. 40 (4): 497–9. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(94)70221-7. PMID 7523233.

- ^ Holt A, Patel M, Ahmed M (2004). "Palliation of patients with malignant gastroduodenal obstruction with self-expanding metallic stents: the treatment of choice?". Gastrointest Endosc. 60 (6): 1010–7. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02276-X. PMID 15605026.

- ^ Fiorini A, Fleischer D, Valero J, Israeli E, Wengrower D, Goldin E (2000). "Self-expandable metal coil stents in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures refractory to conventional therapy: a case series". Gastrointest Endosc. 52 (2): 259–62. doi:10.1067/mge.2000.107709. PMID 10922106.

- ^ Gelbmann C, Ratiu N, Rath H, Rogler G, Lock G, Schölmerich J, Kullmann F (2004). "Use of self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of esophageal perforations and symptomatic anastomotic leaks". Endoscopy. 36 (8): 695–9. doi:10.1055/s-2004-825656. PMID 15280974.

- ^ a b Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Mizuguchi Y, Shimizu T, Aimoto T, Nakamura Y, Nomura T, Yokomuro S, Arima Y, Uchida E, Misawa H, Uchida E, Tajiri T (2006). "Fracture of an expandable metallic stent placed for biliary obstruction due to common bile duct carcinoma". Journal of Nippon Medical School. 73 (3): 164–8. doi:10.1272/jnms.73.164. PMID 16790985.

- ^ Kauffmann G, Roeren T, Friedl P, Brambs H, Richter G (1990). "Interventional radiological treatment of malignant biliary obstruction". Eur J Surg Oncol. 16 (4): 397–403. PMID 2199224.

- ^ Cordero J, Moores D (2000). "Self-expanding esophageal metallic stents in the treatment of esophageal obstruction". Am Surg. 66 (10): 956–8, discussion 958–9. PMID 11261624.

- ^ Ramirez F, Dennert B, Zierer S, Sanowski R (1997). "Esophageal self-expandable metallic stents--indications, practice, techniques, and complications: results of a national survey". Gastrointest Endosc. 45 (5): 360–4. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(97)70144-5. PMID 9165315.

- ^ Schiefke I, Zabel-Langhennig A, Wiedmann M, Huster D, Witzigmann H, Mössner J, Berr F, Caca K (2003). "Self-expandable metallic stents for malignant duodenal obstruction caused by biliary tract cancer". Gastrointest Endosc. 58 (2): 213–9. doi:10.1067/mge.2003.362. PMID 12872088.

- ^ Yoon W, Lee J, Lee K, Lee W, Ryu J, Kim Y, Yoon Y (2006). "A comparison of covered and uncovered Wallstents for the management of distal malignant biliary obstruction". Gastrointest Endosc. 63 (7): 996–1000. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.054. PMID 16733115.

- ^ Garcia-Cano J; Gonzalez-Huix F; Juzgado D; Igea F; Perez-Miranda M; Lopez-Roses L; Rodriguez A; Gonzalez-Carro P; Yuguero L; Espinos J; Ducons J; Orive V; Rodriguez S. (2006). "Use of self-expanding metal stents to treat malignant colorectal obstruction in general endoscopic practice (with videos)". Gastrointest Endosc. 64 (6): 914–920. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.034. PMID 17140898.

- ^ Vakil N, Morris A, Marcon N, Segalin A, Peracchia A, Bethge N, Zuccaro G, Bosco J, Jones W (2001). "A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of covered expandable metal stents in the palliation of malignant esophageal obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction". Am J Gastroenterol. 96 (6): 1791–6. PMID 11419831.

- ^ Conio M, Gostout C (1998). "Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of tumor ingrowth in expandable esophageal stents". Gastrointest Endosc. 48 (2): 225. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(98)70175-0. PMID 9717799.

- ^ Matsushita M, Takakuwa H, Nishio A, Kido M, Shimeno N (2003). "Open-biopsy-forceps technique for endoscopic removal of distally migrated and impacted biliary metallic stents". Gastrointest Endosc. 58 (6): 924–7. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(03)02335-6. PMID 14652567.

- ^ Grover SC, Wang CS, Jones MB, Elyas ME, Kortan PP. "Iatrogenic intussusception of a self-expanding metallic esophageal stent in stent after endoscopic guidewire trauma. Abstract presented at Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Meetings, February 2006". Retrieved 2006-12-07.