Therapsida: Difference between revisions

Hemiauchenia (talk | contribs) Expanded |

Ornithopsis (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

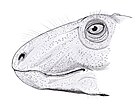

[[Image:Pristeroognathus DB.jpg|thumb|left|Illustration of ''[[Pristerognathus]]'', a cat-sized [[therocephalia]]n therapsid]] |

[[Image:Pristeroognathus DB.jpg|thumb|left|Illustration of ''[[Pristerognathus]]'', a cat-sized [[therocephalia]]n therapsid]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Compared to their [[pelycosaur]]ian ancestors, early therapsids had very similar [[skull]]s but very different [[post-cranial]] [[Morphology (biology)|morphology]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | Therapsids' [[temporal fenestra]]e were larger than those of the pelycosaurs. The jaws of some therapsids were more complex and powerful, and the [[teeth]] were differentiated into frontal [[incisor]]s for nipping, great lateral [[canine tooth|canines]] for puncturing and tearing, and [[molar (tooth)|molars]] for shearing and chopping food. |

||

===Posture=== |

|||

===Legs and feet=== |

|||

Therapsid legs were positioned more vertically beneath their bodies than were the sprawling legs of [[reptile]]s and pelycosaurs. Also compared to these groups, the feet were more symmetrical, with the first and last toes short and the middle toes long, an indication that the foot's [[Axis (anatomy)|axis]] was placed parallel to that of the animal, not sprawling out sideways. This orientation would have given a more [[mammal]]-like gait than the [[lizard]]-like gait of the pelycosaurs.<ref>{{cite book|last=Carroll|author-link=Robert L. Carroll|first=R. L.|title=Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution|year=1988|publisher=W. H. Freeman and Company|location=New York|isbn=978-0-7167-1822-2|pages=[https://archive.org/details/vertebratepaleon0000carr/page/698 698]|title-link=Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution}}</ref> |

Therapsid legs were positioned more vertically beneath their bodies than were the sprawling legs of [[reptile]]s and pelycosaurs. Also compared to these groups, the feet were more symmetrical, with the first and last toes short and the middle toes long, an indication that the foot's [[Axis (anatomy)|axis]] was placed parallel to that of the animal, not sprawling out sideways. This orientation would have given a more [[mammal]]-like gait than the [[lizard]]-like gait of the pelycosaurs.<ref>{{cite book|last=Carroll|author-link=Robert L. Carroll|first=R. L.|title=Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution|year=1988|publisher=W. H. Freeman and Company|location=New York|isbn=978-0-7167-1822-2|pages=[https://archive.org/details/vertebratepaleon0000carr/page/698 698]|title-link=Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution}}</ref> |

||

===Physiology=== |

|||

The physiology of therapsids is poorly understood. Most Permian therapsids had a pineal foramen, indicating that they had a [[parietal eye]] like many modern reptiles and amphibians. The parietal eye serves an important role in thermoregulation and the circadian rhythm of ectotherms, but is absent in modern mammals, which are endothermic.<ref name=Benoit2016B/> Near the end of the Permian, dicynodonts, therocephalians, and cynodonts show [[parallel evolution|parallel]] trends towards loss of the pineal foramen, and the foramen is completely absent in probainognathian cynodonts. Evidence from oxygen isotopes, which are correlated with body temperature, suggests that most Permian therapsids were ectotherms and that endothermy evolved convergently in dicynodonts and cynodonts near the end of the Permian.<ref name=Rey2017/> In contrast, evidence from histology suggests that endothermy is shared across Therapsida,<ref name=FraureBrac2020/> whereas estimates of blood flow rate and lifespan in the mammaliaform ''[[Morganucodon]]'' suggest that even early mammaliaforms had reptile-like metabolic rates.<ref name=Newham2020/> Evidence for respiratory turbinates, which have been hypothesized to be indicative of endothermy, was reported in the therocephalian ''[[Glanosuchus]]'', but subsequent study showed that the apparent attachment sites for turbinates may simply be the result of distortion of the skull.<ref name=Hopson2012/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Therapsids' [[temporal fenestra]]e were larger than those of the pelycosaurs. The jaws of some therapsids were more complex and powerful, and the [[teeth]] were differentiated into frontal [[incisor]]s for nipping, great lateral [[canine tooth|canines]] for puncturing and tearing, and [[molar (tooth)|molars]] for shearing and chopping food. |

||

===Integument=== |

|||

The evolution of integument in therapsids is poorly known, and there are few fossils that provide direct evidence for the presence or absence of fur. The most basal synapsids with unambiguous direct evidence of fur are [[docodonts]], which are mammaliaforms very closely related to crown-group mammals. Fossilized facial skin from the dinocephalian ''[[Estemmenosuchus]]'' has been described as showing that the skin was glandular and lacked both scales and hair.<ref name=Chudinov1968/> |

|||

[[Coprolites]] containing what appear to be hairs have been found from the [[Permian]].<ref name=Smith2011/><ref name=Bajdek2016/> Though the source of these hairs is not known with certainty, they may suggest that hair was present in at least some Permian therapsids. |

|||

The closure of the pineal foramen in probainognathian cynodonts may indicate a mutation in the regulatory gene Msx2, which is involved in both the closure of the skull roof and the maintenance of hair follicles in mice.<ref name=Benoit2016A/> This suggests that hair may have first evolved in probainognathians, though it does not entirely rule out an earlier origin of fur.<ref name=Benoit2016A/> |

|||

===Fur and endothermy=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Whiskers probably evolved in probainognathian cynodonts.<ref name=Benoit2016A/><ref name=Benoit2020/> Some studies had inferred an earlier origin for whiskers based on the presence of foramina on the snout of therocephalians and early cynodonts, but the arrangement of foramina in these taxa actually closely resembles lizards,<ref name=Estes1961/> which would make the presence of mammal-like whiskers unlikely.<ref name=Benoit2020/> |

|||

Recent studies on [[Permian]] [[coprolite]]s showcase that [[hair]] was present in at least some therapsids.<ref name="Microbiota"/> Hair was confirmed to be present in the [[docodont]] ''[[Castorocauda]]'' and several contemporary [[haramiyida]]ns, and whiskers are inferred from [[therocephalia]]ns and [[cynodont]]s. |

|||

==Evolutionary history== |

==Evolutionary history== |

||

| Line 146: | Line 153: | ||

<ref name=Abdala2008>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00784.x| issn = 1475-4983| volume = 51| issue = 4| pages = 1011–1024| last1 = Abdala| first1 = Fernando| last2 = Rubidge| first2 = Bruce S.| last3 = van den Heever| first3 = Juri| title = The oldest therocephalians (Therapsida, Eutheriodontia) and the early diversification of Therapsida| journal = Palaeontology| date = 2008| url = http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00784.x}}</ref> |

<ref name=Abdala2008>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00784.x| issn = 1475-4983| volume = 51| issue = 4| pages = 1011–1024| last1 = Abdala| first1 = Fernando| last2 = Rubidge| first2 = Bruce S.| last3 = van den Heever| first3 = Juri| title = The oldest therocephalians (Therapsida, Eutheriodontia) and the early diversification of Therapsida| journal = Palaeontology| date = 2008| url = http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00784.x}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=AngielczykKammerer2018>{{Cite book| publisher = De Gruyter| isbn = 978-3-11-034155-3 | pages = 117–198| editor-first1 = Frank | editor-last1 = Zachos | editor-first2 = Robert | editor-last2 = Asher | last1 = Angielczyk| first1 = Kenneth D.| last2 = Kammerer| first2 = Christian F.| title = Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics| chapter = Non-Mammalian synapsids: the deep roots of the mammalian family tree| date = 2018-10-22| url = https://www.degruyter.com/view/book/9783110341553/10.1515/9783110341553-005.xml}}</ref> |

<ref name=AngielczykKammerer2018>{{Cite book| publisher = De Gruyter| isbn = 978-3-11-034155-3 | pages = 117–198| editor-first1 = Frank | editor-last1 = Zachos | editor-first2 = Robert | editor-last2 = Asher | last1 = Angielczyk| first1 = Kenneth D.| last2 = Kammerer| first2 = Christian F.| title = Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics| chapter = Non-Mammalian synapsids: the deep roots of the mammalian family tree| date = 2018-10-22| url = https://www.degruyter.com/view/book/9783110341553/10.1515/9783110341553-005.xml}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | <ref name=Bajdek2016>{{cite journal |title=Microbiota and food residues including possible evidence of pre-mammalian hair in Upper Permian coprolites from Russia. |first1=Piotr |last1=Bajdek |first2=Martin |last2=Qvarnström |first3=Krzysztof |last3=Owocki |first4=Tomasz |last4=Sulej |first5=Andrey G. |last5=Sennikov |first6=Valeriy K. |last6=Golubev |first7=Grzegorz |last7=Niedźwiedzki. |year=2016 |journal=Lethaia |volume=49 |issue=4 |pages=455–477 |doi=10.1111/let.12156}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Benoit2016A>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1038/srep25604| issn = 2045-2322| volume = 6| issue = 1| pages = 25604| last1 = Benoit| first1 = J.| last2 = Manger| first2 = P. R.| last3 = Rubidge| first3 = B. S.| title = Palaeoneurological clues to the evolution of defining mammalian soft tissue traits| journal = Scientific Reports| date = 2016-05-09| url = http://www.nature.com/articles/srep25604}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Benoit2016B>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.4202/app.00219.2015| issn = 05677920| last1 = Benoit| first1 = Julien| last2 = Abdala| first2 = Fernando| last3 = Manger| first3 = Paul| last4 = Rubidge| first4 = Bruce| title = The sixth sense in mammalians forerunners: variability of the parietal foramen and the evolution of the pineal eye in South African Permo-Triassic eutheriodont therapsids| journal = Acta Palaeontologica Polonica| date = 2016| url = http://www.app.pan.pl/article/item/app002192015.html}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Benoit2020>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1007/s10914-019-09467-8| issn = 1064-7554, 1573-7055| volume = 27| issue = 3| pages = 329–348| last1 = Benoit| first1 = Julien| last2 = Ruf| first2 = Irina| last3 = Miyamae| first3 = Juri A.| last4 = Fernandez| first4 = Vincent| last5 = Rodrigues| first5 = Pablo Gusmão| last6 = Rubidge| first6 = Bruce S.| title = The Evolution of the Maxillary Canal in Probainognathia (Cynodontia, Synapsida): Reassessment of the Homology of the Infraorbital Foramen in Mammalian Ancestors| journal = Journal of Mammalian Evolution| date = 2020 | url = http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10914-019-09467-8}}</ref> |

|||

*<ref name=Chudinov1968>{{Cite journal| volume = 179| pages = 226–229| last = Chudinov| first = P. K.| title = Structure of the integuments of theromorphs | year = 1968 | journal = Doklady Akad. Nauk SSSR }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Estes1961>{{Cite journal| volume = 125| pages = 165–180| last = Estes| first = Richard| title = Cranial anatomy of the cynodont reptile Thrinaxodon liorhinus| journal = Bulletin Museum of Comparative Zoology| date = 1961}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=FraureBrac2020>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1098/rstb.2019.0138| issn = 0962-8436, 1471-2970| volume = 375| issue = 1793| pages = 20190138| last1 = Faure-Brac| first1 = Mathieu G.| last2 = Cubo| first2 = Jorge| title = Were the synapsids primitively endotherms? A palaeohistological approach using phylogenetic eigenvector maps| journal = Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences| date = 2020-03-02| url = https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2019.0138}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Hopson2012>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.3158/2158-5520-5.1.126| issn = 2158-5520, 2163-7105| volume = 5| pages = 126–148| last = Hopson| first = James A.| title = The Role of Foraging Mode in the Origin of Therapsids: Implications for the Origin of Mammalian Endothermy| journal = Fieldiana Life and Earth Sciences| date = 2012-10-18| url = http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.3158/2158-5520-5.1.126}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Newham2020>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1038/s41467-020-18898-4| issn = 2041-1723| volume = 11| issue = 1| pages = 5121| last1 = Newham| first1 = Elis| last2 = Gill| first2 = Pamela G.| last3 = Brewer| first3 = Philippa| last4 = Benton| first4 = Michael J.| last5 = Fernandez| first5 = Vincent| last6 = Gostling| first6 = Neil J.| last7 = Haberthür| first7 = David| last8 = Jernvall| first8 = Jukka| last9 = Kankaanpää| first9 = Tuomas| last10 = Kallonen| first10 = Aki| last11 = Navarro| first11 = Charles| last12 = Pacureanu| first12 = Alexandra| last13 = Richards| first13 = Kelly| last14 = Brown| first14 = Kate Robson| last15 = Schneider| first15 = Philipp| last16 = Suhonen| first16 = Heikki| last17 = Tafforeau| first17 = Paul| last18 = Williams| first18 = Katherine A.| last19 = Zeller-Plumhoff| first19 = Berit| last20 = Corfe| first20 = Ian J.| title = Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals| journal = Nature Communications| date = 2020| url = http://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-18898-4}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Rey2017>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.7554/eLife.28589| issn = 2050-084X| volume = 6| pages = –28589| last1 = Rey| first1 = Kévin| last2 = Amiot| first2 = Romain| last3 = Fourel| first3 = François| last4 = Abdala| first4 = Fernando| last5 = Fluteau| first5 = Frédéric| last6 = Jalil| first6 = Nour-Eddine| last7 = Liu| first7 = Jun| last8 = Rubidge| first8 = Bruce S| last9 = Smith| first9 = Roger MH| last10 = Steyer| first10 = J Sébastien| last11 = Viglietti| first11 = Pia A| last12 = Wang| first12 = Xu| last13 = Lécuyer| first13 = Christophe| title = Oxygen isotopes suggest elevated thermometabolism within multiple Permo-Triassic therapsid clades| journal = eLife| date = 2017-07-18| url = https://elifesciences.org/articles/28589}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Smith2011>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.09.006| issn = 00310182| volume = 312| issue = 1-2| pages = 40–53| last1 = Smith| first1 = Roger M.H.| last2 = Botha-Brink| first2 = Jennifer| title = Morphology and composition of bone-bearing coprolites from the Late Permian Beaufort Group, Karoo Basin, South Africa| journal = Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology| date = 2011| url = https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0031018211004792}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 00:21, 6 December 2021

| Therapsids Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| From top to bottom and left to right, several examples of non-mammalian therapsids: Biarmosuchus (Biarmosuchia), Moschops (Dinocephalia), Myosaurus (Anomodontia), Inostrancevia (Gorgonopsia), Pristerognathus (Therocephalia) and Brasilitherium (Cynodontia) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Sphenacodontia |

| Clade: | Pantherapsida |

| Clade: | Sphenacodontoidea |

| Clade: | Therapsida Broom, 1905 |

| Clades | |

Therapsida[a] is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors.[1][2] Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more underneath the body, as opposed to the sprawling posture of many reptiles and salamanders. The earliest fossil attributed to Therapsida used to be Tetraceratops insignis from the Lower Permian.[3][4] However, in 2020 a study concluded that Tetraceratops is not a true therapsid, but should be considered a member of the more ancient Sphenacodontia, from which the therapsids evolved.[5]

Therapsids evolved from "pelycosaurs", specifically within the Sphenacodontia, more than 272 million years ago. They replaced the "pelycosaurs" as the dominant large land animals in the Middle Permian through to the Early Triassic. In the aftermath of the Permian–Triassic extinction event, therapsids declined in relative importance to the rapidly diversifying reptiles during the Middle Triassic.

The therapsids include the cynodonts, the group that gave rise to mammals in the Late Triassic around 225 million years ago. Of the non-mammalian therapsids, only cynodonts survived the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. The last remaining non-mammalian cynodonts were the tritylodonts, which persisted into the Early Cretacepus.

Characteristics

Jaw and teeth

Therapsids' temporal fenestrae were larger than those of the pelycosaurs. The jaws of some therapsids were more complex and powerful, and the teeth were differentiated into frontal incisors for nipping, great lateral canines for puncturing and tearing, and molars for shearing and chopping food.

Posture

Therapsid legs were positioned more vertically beneath their bodies than were the sprawling legs of reptiles and pelycosaurs. Also compared to these groups, the feet were more symmetrical, with the first and last toes short and the middle toes long, an indication that the foot's axis was placed parallel to that of the animal, not sprawling out sideways. This orientation would have given a more mammal-like gait than the lizard-like gait of the pelycosaurs.[6]

Physiology

The physiology of therapsids is poorly understood. Most Permian therapsids had a pineal foramen, indicating that they had a parietal eye like many modern reptiles and amphibians. The parietal eye serves an important role in thermoregulation and the circadian rhythm of ectotherms, but is absent in modern mammals, which are endothermic.[7] Near the end of the Permian, dicynodonts, therocephalians, and cynodonts show parallel trends towards loss of the pineal foramen, and the foramen is completely absent in probainognathian cynodonts. Evidence from oxygen isotopes, which are correlated with body temperature, suggests that most Permian therapsids were ectotherms and that endothermy evolved convergently in dicynodonts and cynodonts near the end of the Permian.[8] In contrast, evidence from histology suggests that endothermy is shared across Therapsida,[9] whereas estimates of blood flow rate and lifespan in the mammaliaform Morganucodon suggest that even early mammaliaforms had reptile-like metabolic rates.[10] Evidence for respiratory turbinates, which have been hypothesized to be indicative of endothermy, was reported in the therocephalian Glanosuchus, but subsequent study showed that the apparent attachment sites for turbinates may simply be the result of distortion of the skull.[11]

Integument

The evolution of integument in therapsids is poorly known, and there are few fossils that provide direct evidence for the presence or absence of fur. The most basal synapsids with unambiguous direct evidence of fur are docodonts, which are mammaliaforms very closely related to crown-group mammals. Fossilized facial skin from the dinocephalian Estemmenosuchus has been described as showing that the skin was glandular and lacked both scales and hair.[12]

Coprolites containing what appear to be hairs have been found from the Permian.[13][14] Though the source of these hairs is not known with certainty, they may suggest that hair was present in at least some Permian therapsids.

The closure of the pineal foramen in probainognathian cynodonts may indicate a mutation in the regulatory gene Msx2, which is involved in both the closure of the skull roof and the maintenance of hair follicles in mice.[15] This suggests that hair may have first evolved in probainognathians, though it does not entirely rule out an earlier origin of fur.[15]

Whiskers probably evolved in probainognathian cynodonts.[15][16] Some studies had inferred an earlier origin for whiskers based on the presence of foramina on the snout of therocephalians and early cynodonts, but the arrangement of foramina in these taxa actually closely resembles lizards,[17] which would make the presence of mammal-like whiskers unlikely.[16]

Evolutionary history

Therapsids evolved from a group of pelycosaurs called sphenacodonts.[18][19] Therapsids became the dominant land animals in the Middle Permian, displacing the pelycosaurs. Therapsida consists of four major clades: the dinocephalians, the herbivorous anomodonts, the carnivorous biarmosuchians, and the mostly carnivorous theriodonts. After a brief burst of evolutionary diversity, the dinocephalians died out in the later Middle Permian (Guadalupian) but the anomodont dicynodonts as well as the theriodont gorgonopsians and therocephalians flourished, being joined at the very end of the Permian by the first of the cynodonts.

Like all land animals, the therapsids were seriously affected by the Permian–Triassic extinction event; the very successful gorgonopsians and the biarmosuchians dying out altogether and the remaining groups—dicynodonts, therocephalians, and cynodonts—reduced to a handful of species each by the earliest Triassic. The dicynodonts, now represented by a single group of large stocky herbivores, the Kannemeyeriiformes, and the medium-sized cynodonts (including both carnivorous and herbivorous forms), flourished worldwide throughout the Early and Middle Triassic. They disappear from the fossil record across much of Pangea at the end of the Carnian (Late Triassic), although they continued for some time longer in the wet equatorial band and the south.

Some exceptions were the still further derived eucynodonts. At least three groups of them survived. They all appeared in the Late Triassic period. The extremely mammal-like family, Tritylodontidae, survived into the Early Cretaceous. Another extremely mammal-like family, Tritheledontidae, are unknown later than the Early Jurassic. Mammaliaformes was the third group, including Morganucodon and similar animals. Some taxonomists refer to these animals as "mammals", though most limit the term to the mammalian crown group.

The non-eucynodont cynodonts survived the Permian–Triassic extinction; Thrinaxodon, Galesaurus and Platycraniellus are known from the Early Triassic. By the Middle Triassic, however, only the eucynodonts remained.

The therocephalians, relatives of the cynodonts, managed to survive the Permian-Triassic extinction and continued to diversify through the Early Triassic period. Approaching the end of the period, however, the therocephalians were in decline to eventual extinction, likely outcompeted by the rapidly diversifying Saurian lineage of diapsids, equipped with sophisticated respiratory systems better suited to the very hot, dry and oxygen-poor world of the End-Triassic.

Dicynodonts were among the most successful groups of therapsids during the Late Permian, and survived through to near the end of the Triassic.

Mammals are the only living therapsids. The mammalian crown group, which evolved in the Early Jurassic period, radiated from a group of mammaliaforms that included the docodonts. The mammaliaforms themselves evolved from probainognathians, a lineage of the eucynodont suborder.

Classification

| The Hopson and Barghausen paradigm for therapsid relationships |

Six major groups of therapsids are generally recognized: Biarmosuchia, Dinocephalia, Anomodontia, Gorgonopsia, Therocephalia, and Cynodontia. A clade uniting therocephalians and cynodonts, called Eutheriodontia, is well-supported, but relationships among the other four clades are controversial.[20] The most widely accepted hypothesis of therapsid relationships, the Hopson and Barghausen paradigm, was first proposed in 1986. Under this hypothesis, biarmosuchians are the earliest-diverging major therapsid group, with the other five groups forming the Eutherapsida, and within Eutherapsida, gorgonopsians are the sister taxon of eutheriodonts, together forming the Theriodontia. Hopson and Barghausen did not initially come to a conclusion about how dinocephalians, anomodonts, and theriodonts were related to each other, but subsequent studies suggested that anomodonts and theriodonts should be classified together as the Neotherapsida. However, there remains debate over these relationships; in particular, some studies have suggested that anomodonts, not gorgonopsians, are the sister taxon of Eutheriodontia, other studies have found dinocephalians and anomodonts to form a clade, and both the phylogenetic position and monophyly of Biarmosuchia remain controversial.

In addition to the six major groups, there are several other lineages and species of uncertain classification. Raranimus from the early Middle Permian of China is likely to be the earliest-diverging known therapsid.[21]

Biarmosuchia

Biarmosuchia is the most recently-recognized therapsid clade, first recognized as a distinct lineage by Hopson and Barghausen in 1986 and formally named by Sigogneau-Russell in 1989. Most biarmosuchians were previously classified as gorgonopsians. Biarmosuchia includes the distinctive Burnetiamorpha, but support for the monophyly of Biarmosuchia is relatively low. Many biarmosuchians are known for extensive cranial ornamentation.

Dinocephalia

Dinocephalia comprises two distinctive groups, the Anteosauria and Tapinocephalia.

Historically, carnivorous dinocephalians, including both anteosaurs and titanosuchids, were called titanosuchians and classified as members of Theriodontia, while the herbivorous Tapinocephalidae were classified as members of Anomodontia.

Anomodontia

Anomodontia includes the dicynodonts, a clade of tusked, beaked herbivores, and the most diverse and long-lived clade of non-cynodont therapsids. Other members of Anomodontia include Suminia, which is thought to have been a climbing form.

Gorgonopsia

Gorgonopsia is an abundant but morphologically homogeneous group of saber-toothed predators.

Therocephalia

It has been suggested that Therocephalia might not be monophyletic, with some species more closely related to cynodonts than others.[22] However, most studies regard Therocephalia as monophyletic.

Cynodontia

Cynodonts are the most diverse and longest-lived of the therapsid groups, as Cynodontia includes mammals. Cynodonts are the only major therapsid clade to lack a Middle Permian fossil record, with the earliest-known cynodont being Charassognathus from the Wuchiapingian age of the Late Permian. Non-mammalian cynodonts include both carnivorous and herbivorous forms.

Gallery

-

Lystrosaurus, an anomodont.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Romer, A. S. (1966) [1933]. Vertebrate Paleontology (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- ^ therapsid (fossil reptile order) - Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Laurin, M.; Reisz, R. R. (1996). "The osteology and relationships of Tetraceratops insignis, the oldest known therapsid". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011287.

- ^ Liu, J.; Rubidge, B.; Li, J. (2009). "New basal synapsid supports Laurasian origin for therapsids". Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 54 (3): 393–400. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0071.

- ^ Spindler, Frederik (2020). "The skull of Tetraceratops insignis (Synapsida, Sphenacodontia)". Palaeovertebrata. 43 (1): e1. doi:10.18563/pv.43.1.e1.

- ^ Carroll, R. L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 698. ISBN 978-0-7167-1822-2.

- ^ Benoit, Julien; Abdala, Fernando; Manger, Paul; Rubidge, Bruce (2016). "The sixth sense in mammalians forerunners: variability of the parietal foramen and the evolution of the pineal eye in South African Permo-Triassic eutheriodont therapsids". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.00219.2015. ISSN 0567-7920.

- ^ Rey, Kévin; Amiot, Romain; Fourel, François; Abdala, Fernando; Fluteau, Frédéric; Jalil, Nour-Eddine; Liu, Jun; Rubidge, Bruce S; Smith, Roger MH; Steyer, J Sébastien; Viglietti, Pia A; Wang, Xu; Lécuyer, Christophe (18 July 2017). "Oxygen isotopes suggest elevated thermometabolism within multiple Permo-Triassic therapsid clades". eLife. 6: –28589. doi:10.7554/eLife.28589. ISSN 2050-084X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Faure-Brac, Mathieu G.; Cubo, Jorge (2 March 2020). "Were the synapsids primitively endotherms? A palaeohistological approach using phylogenetic eigenvector maps". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 375 (1793): 20190138. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0138. ISSN 1471-2970 0962-8436, 1471-2970.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ Newham, Elis; Gill, Pamela G.; Brewer, Philippa; Benton, Michael J.; Fernandez, Vincent; Gostling, Neil J.; Haberthür, David; Jernvall, Jukka; Kankaanpää, Tuomas; Kallonen, Aki; Navarro, Charles; Pacureanu, Alexandra; Richards, Kelly; Brown, Kate Robson; Schneider, Philipp; Suhonen, Heikki; Tafforeau, Paul; Williams, Katherine A.; Zeller-Plumhoff, Berit; Corfe, Ian J. (2020). "Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5121. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18898-4. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ Hopson, James A. (18 October 2012). "The Role of Foraging Mode in the Origin of Therapsids: Implications for the Origin of Mammalian Endothermy". Fieldiana Life and Earth Sciences. 5: 126–148. doi:10.3158/2158-5520-5.1.126. ISSN 2163-7105 2158-5520, 2163-7105.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ Chudinov, P. K. (1968). "Structure of the integuments of theromorphs". Doklady Akad. Nauk SSSR. 179: 226–229.

- ^ Smith, Roger M.H.; Botha-Brink, Jennifer (2011). "Morphology and composition of bone-bearing coprolites from the Late Permian Beaufort Group, Karoo Basin, South Africa". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 312 (1–2): 40–53. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.09.006. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Bajdek, Piotr; Qvarnström, Martin; Owocki, Krzysztof; Sulej, Tomasz; Sennikov, Andrey G.; Golubev, Valeriy K.; Niedźwiedzki., Grzegorz (2016). "Microbiota and food residues including possible evidence of pre-mammalian hair in Upper Permian coprolites from Russia". Lethaia. 49 (4): 455–477. doi:10.1111/let.12156.

- ^ a b c Benoit, J.; Manger, P. R.; Rubidge, B. S. (9 May 2016). "Palaeoneurological clues to the evolution of defining mammalian soft tissue traits". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 25604. doi:10.1038/srep25604. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ a b Benoit, Julien; Ruf, Irina; Miyamae, Juri A.; Fernandez, Vincent; Rodrigues, Pablo Gusmão; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2020). "The Evolution of the Maxillary Canal in Probainognathia (Cynodontia, Synapsida): Reassessment of the Homology of the Infraorbital Foramen in Mammalian Ancestors". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 27 (3): 329–348. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09467-8. ISSN 1573-7055 1064-7554, 1573-7055.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ Estes, Richard (1961). "Cranial anatomy of the cynodont reptile Thrinaxodon liorhinus". Bulletin Museum of Comparative Zoology. 125: 165–180.

- ^ Synapsid Classification & Apomorphies

- ^ Huttenlocker, Adam. K.; Rega, Elizabeth (2012). "Chapter 4. The Paleobiology and Bone Microstructure of Pelycosauriangrade Synapsids". In Chinsamy-Turan, Anusuya (ed.). Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation, Histology, Biology. Indiana University Press. pp. 90–119. ISBN 978-0253005335.

- ^ Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Kammerer, Christian F. (22 October 2018). "Non-Mammalian synapsids: the deep roots of the mammalian family tree". In Zachos, Frank; Asher, Robert (eds.). Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics. De Gruyter. pp. 117–198. ISBN 978-3-11-034155-3.

- ^ Duhamel, A.; Benoit, J.; Rubidge, B. S.; Liu, J. (2021-08). "A re-assessment of the oldest therapsid Raranimus confirms its status as a basal member of the clade and fills Olson's gap". The Science of Nature. 108 (4): 26. doi:10.1007/s00114-021-01736-y. ISSN 0028-1042.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Abdala, Fernando; Rubidge, Bruce S.; van den Heever, Juri (2008). "The oldest therocephalians (Therapsida, Eutheriodontia) and the early diversification of Therapsida". Palaeontology. 51 (4): 1011–1024. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00784.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

Further reading

- Benton, M. J. (2004). Vertebrate Palaeontology, 3rd ed., Blackwell Science.

- Carroll, R. L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology & Evolution. W. H. Freeman & Company, New York.

- Kemp, T. S. (2005). The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford University Press.

- Romer, A. S. (1966). Vertebrate Paleontology. University of Chicago Press, 1933; 3rd ed.

- Bennett, A. F., & Ruben, J. A. (1986). "The metabolic and thermoregulatory status of therapsids." In The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 207-218.

External links

- "Therapsida: Mammals and extinct relatives" Tree of Life

- "Therapsida: overview" Palaeos