Planck constant: Difference between revisions

m →Names |

|||

| Line 143: | Line 143: | ||

--><ref name="Oxford Planck constant">{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Planck constant |encyclopedia=A Dictionary of Physics |publisher=OUP Oxford |location=Oxford,UK |url={{google books|plainurl=y|id=YPmFDwAAQBAJ}} |date=2017 |editor-last=Rennie |editor-first=Richard |isbn=978-0198821472 |editor2-last=Law |editor2-first=Jonathan|edition= 7th|series=Oxford Quick Reference}}</ref>{{rp|page=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Dictionary_of_Science/40RdDgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22physics)%20the%20rationalized%20Planck%20constant%20(or%20Dirac%20constant)%22&pg=PT1470&printsec=frontcover 726]}} <!-- |

--><ref name="Oxford Planck constant">{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Planck constant |encyclopedia=A Dictionary of Physics |publisher=OUP Oxford |location=Oxford,UK |url={{google books|plainurl=y|id=YPmFDwAAQBAJ}} |date=2017 |editor-last=Rennie |editor-first=Richard |isbn=978-0198821472 |editor2-last=Law |editor2-first=Jonathan|edition= 7th|series=Oxford Quick Reference}}</ref>{{rp|page=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Dictionary_of_Science/40RdDgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22physics)%20the%20rationalized%20Planck%20constant%20(or%20Dirac%20constant)%22&pg=PT1470&printsec=frontcover 726]}} <!-- |

||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

||

--> |

--><ref>{{cite book |title=The International Encyclopedia of Physical Chemistry and Chemical Physics |date=1960 |publisher=Pergamon Press |url=https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_International_Encyclopedia_of_Physic/ufTvAAAAMAAJ |language=en}}</ref>{{rp|page=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_International_Encyclopedia_of_Physic/ufTvAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22rationalized%20Planck%22&printsec=frontcover 10]}} <!-- |

||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

|||

--><ref>{{cite book |last1=Vértes |first1=Attila |last2=Nagy |first2=Sándor |last3=Klencsár |first3=Zoltán |last4=Lovas |first4=Rezso György |last5=Rösch |first5=Frank |title=Handbook of Nuclear Chemistry|date=10 December 2010 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-1-4419-0719-6 |url=https://www.google.com/books/edition/Handbook_of_Nuclear_Chemistry/NQyF6KaUScQC |language=en}}</ref>{{rp|page=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/Handbook_of_Nuclear_Chemistry/NQyF6KaUScQC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22called+rationalized+Planck+constant%22&pg=PT616&printsec=frontcover -]}} <!-- |

|||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

|||

-->(or '''rationalized Planck's constant'''<!-- |

|||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

|||

--><ref name="Bethe and Salpeter">{{cite book |editor-last1=Flügge |editor-first1=Siegfried |editor-link1=Siegfried Flügge|title=Handbuch der Physik: Atome I-II |date=1957 |publisher=Springer |url=https://www.google.com/books/edition/Handbuch_der_Physik_Atome_I_II/A-APAQAAMAAJ |last1=Bethe |first1=Hans A. |author-link1=Hans Bethe|last2=Salpeter |first2=Edwin E. |author-link2=Edwin E. Salpeter|chapter=Quantum Mechanics of One- and Two-Electron Atoms |language=en}}</ref>{{rp|page=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/Handbuch_der_Physik_Atome_I_II/A-APAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=rationalized 334]}} <!-- |

|||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

|||

--><ref>{{cite book |last1=Lang |first1=Kenneth |title=Astrophysical Formulae: A Compendium for the Physicist and Astrophysicist |date=11 November 2013 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-3-662-11188-8 |url=https://www.google.com/books/edition/Astrophysical_Formulae/LyzrCAAAQBAJ |language=en}}</ref>{{rp|page=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/Astrophysical_Formulae/LyzrCAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Astrophysical+Formulae%22+%22rationalized+Planck%27s%22&pg=PR9&printsec=frontcover ix]}} <!-- |

|||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

|||

--><ref>{{cite book |last1=Galgani |first1=L. |last2=Carati |first2=A. |last3=Pozzi |first3=B. |chapter=The Problem of the Rate of Thermalization, and the Relations between Classical and Quantum Mechanics |date=December 2002 |pages=111–122 |doi=10.1142/9789812776273_0011|editor-last1=Fabrizio|editor-first1=Mauro |editor-last2=Morro|editor-first2=Angelo|title=Mathematical Models and Methods for Smart Materials, Cortona, Italy, 25 – 29 June 2001|date=December 2002 }}</ref>{{rp|page=[https://www.google.com/books/edition/Mathematical_Models_and_Methods_for_Smar/wDRpDQAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22is+the+(rationalized)+Planck%27s+constant%22&pg=PA112&printsec=frontcover 112]}} <!-- |

|||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

||

-->), the '''Dirac constant'''<!-- |

-->), the '''Dirac constant'''<!-- |

||

| Line 253: | Line 263: | ||

--><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Bais |first1=F. Alexander |title=Philosophy of Information |last2=Farmer |first2=J. Doyne | author-link2=J. Doyne Farmer|date=2008 |publisher=North-Holland |isbn=978-0-444-51726-5 |editor-last=Adriaans |editor-first=Pieter |series=Handbook of the Philosophy of Science |volume=8 |publication-place=Amsterdam |chapter=The Physics of Information |editor-last2=van Benthem |editor-first2=Johan |editor-link2=Johan van Benthem (logician) |chapter-url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780444517265500200 |arxiv=0708.2837}}</ref>{{rp|pages=653}}}} <!-- |

--><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Bais |first1=F. Alexander |title=Philosophy of Information |last2=Farmer |first2=J. Doyne | author-link2=J. Doyne Farmer|date=2008 |publisher=North-Holland |isbn=978-0-444-51726-5 |editor-last=Adriaans |editor-first=Pieter |series=Handbook of the Philosophy of Science |volume=8 |publication-place=Amsterdam |chapter=The Physics of Information |editor-last2=van Benthem |editor-first2=Johan |editor-link2=Johan van Benthem (logician) |chapter-url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780444517265500200 |arxiv=0708.2837}}</ref>{{rp|pages=653}}}} <!-- |

||

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

***spacing for readability of reference*** |

||

-->while retaining the relationship <math display="inline">\hbar\, {{=}} h/(2 \pi)</math>. |

-->while retaining the relationship <math display="inline">\hbar\, {{=}} h/(2 \pi)</math>. |

||

==== Symbols ==== |

==== Symbols ==== |

||

Revision as of 21:02, 5 October 2023

| Planck constant | |

|---|---|

Common symbols | |

| Dimension | |

| Reduced Planck constant | |

|---|---|

Common symbols | |

Derivations from other quantities | |

| Dimension | |

The Planck constant, or Planck's constant, denoted by ,[1] is a fundamental physical constant[1] of foundational importance in quantum mechanics: a photon's energy is equal to its frequency multiplied by the Planck constant, and the wavelength of a matter wave equals the Planck constant divided by the associated particle momentum.

The constant was first postulated by Max Planck in 1900 as a proportionality constant needed to explain experimental black-body radiation.[2] Planck later referred to the constant as the "quantum of action".[3] In 1905, Albert Einstein associated the "quantum" or minimal element of the energy to the electromagnetic wave itself. Max Planck received the 1918 Nobel Prize in Physics "in recognition of the services he rendered to the advancement of Physics by his discovery of energy quanta".

In metrology, the Planck constant is used, together with other constants, to define the kilogram, the SI unit of mass.[4] The SI units are defined in such a way that, when the Planck constant is expressed in SI units, it has the exact value = 6.62607015×10−34 J⋅Hz−1.[5][6] It is often used with units of eV, which corresponds to the SI unit per elementary charge.

| Constant | SI units | Units with eV |

|---|---|---|

| h | 6.62607015×10−34 J⋅Hz−1[5] | 4.135667696...×10−15 eV⋅Hz−1[7] |

| ħ | 1.054571817...×10−34 J⋅s[8] | 6.582119569...×10−16 eV⋅s[9] |

Reduced Planck constant ℏ

In many applications, the Planck constant naturally appears in combination with as , which can be traced to the fact that in these applications it is natural to use the angular frequency (in radians per second) rather than plain frequency (in cycles per second or hertz). For this reason, is often useful to absorb that factor of 2π into the Planck constant by introducing the reduced Planck constant[10][11]: 482 (or reduced Planck's constant[12]: 5 [13]: 788 ), equal to the Planck constant divided by [10] and denoted by (pronounced h-bar[14]: 336 ).

Many of the most important equations, relations, definitions, and results of quantum mechanics are customarily written using the reduced Planck constant rather than the Planck constant , including the Schrödinger equation, momentum operator, canonical commutation relation, Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, and Planck units.[15]: 104

History

The combination first made its appearance[a] in Niels Bohr's 1913 paper,[20]: 15 where it was denoted by .[b] For the next 15 years, the combination continued to appear in the literature, but normally without a separate symbol.[c] Then, in 1926, in their seminal papers, Schrödinger and Dirac again introduced special symbols for it: in the case of Schrödinger,[33] and in the case of Dirac.[34] Dirac continued to use in this way until 1930,[35]: 291 when he introduced the symbol in his book The Principles of Quantum Mechanics.[35]: 291 [36]

More on terminology and notation

Names

The reduced Planck constant is known by many other names: the rationalized Planck constant[37]: 726 [38]: 10 [39]: - (or rationalized Planck's constant[40]: 334 [41]: ix [42]: 112 ), the Dirac constant[43]: 275 [37]: 726 [44]: xv (or Dirac's constant[45]: 148 [46]: 604 [47]: 313 ), the Dirac [48][49]: xviii (or Dirac's [50]: 17 ), the Dirac [51]: 187 (or Dirac's [52]: 273 [53]: 14 ), and h-bar.[54]: 558 [55]: 561 It is also common to refer to this as “Planck's constant”[56]: 55 [d] while retaining the relationship .

Symbols

By far the most common symbol for the reduced Planck constant is . However, there are some sources that denote it by instead, in which case they usually refer to it as the “Dirac ”[82]: 43 [83]: 151 (or “Dirac's ”[84]: 21 ).

Origin of the constant

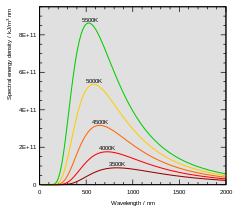

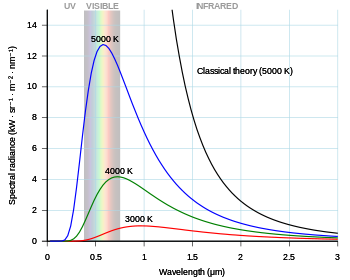

Planck's constant was formulated as part of Max Planck's successful effort to produce a mathematical expression that accurately predicted the observed spectral distribution of thermal radiation from a closed furnace (black-body radiation).[85] This mathematical expression is now known as Planck's law.

In the last years of the 19th century, Max Planck was investigating the problem of black-body radiation first posed by Kirchhoff some 40 years earlier. Every physical body spontaneously and continuously emits electromagnetic radiation. There was no expression or explanation for the overall shape of the observed emission spectrum. At the time, Wien's law fit the data for short wavelengths and high temperatures, but failed for long wavelengths.[85]: 141 Also around this time, but unknown to Planck, Lord Rayleigh had derived theoretically a formula, now known as the Rayleigh–Jeans law, that could reasonably predict long wavelengths but failed dramatically at short wavelengths.

Approaching this problem, Planck hypothesized that the equations of motion for light describe a set of harmonic oscillators, one for each possible frequency. He examined how the entropy of the oscillators varied with the temperature of the body, trying to match Wien's law, and was able to derive an approximate mathematical function for the black-body spectrum,[2] which gave a simple empirical formula for long wavelengths.

Planck tried to find a mathematical expression that could reproduce Wien's law (for short wavelengths) and the empirical formula (for long wavelengths). This expression included a constant, , which is thought to be for Hilfsgrösse (auxiliary variable),[86] and subsequently became known as the Planck constant. The expression formulated by Planck showed that the spectral radiance of a body for frequency ν at absolute temperature T is given by

- ,

where is the Boltzmann constant, is the Planck constant, and is the speed of light in the medium, whether material or vacuum.[87][88][89]

The spectral radiance of a body, , describes the amount of energy it emits at different radiation frequencies. It is the power emitted per unit area of the body, per unit solid angle of emission, per unit frequency. The spectral radiance can also be expressed per unit wavelength instead of per unit frequency. In this case, it is given by

- ,

showing how radiated energy emitted at shorter wavelengths increases more rapidly with temperature than energy emitted at longer wavelengths.[90]

Planck's law may also be expressed in other terms, such as the number of photons emitted at a certain wavelength, or the energy density in a volume of radiation. The SI units of are W·sr−1·m−2·Hz−1, while those of are W·sr−1·m−3.

Planck soon realized that his solution was not unique. There were several different solutions, each of which gave a different value for the entropy of the oscillators.[2] To save his theory, Planck resorted to using the then-controversial theory of statistical mechanics,[2] which he described as "an act of desperation".[91] One of his new boundary conditions was

to interpret UN [the vibrational energy of N oscillators] not as a continuous, infinitely divisible quantity, but as a discrete quantity composed of an integral number of finite equal parts. Let us call each such part the energy element ε;

— Planck, On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum[2]

With this new condition, Planck had imposed the quantization of the energy of the oscillators, "a purely formal assumption … actually I did not think much about it ..." in his own words,[92] but one that would revolutionize physics. Applying this new approach to Wien's displacement law showed that the "energy element" must be proportional to the frequency of the oscillator, the first version of what is now sometimes termed the "Planck–Einstein relation":

Planck was able to calculate the value of from experimental data on black-body radiation: his result, 6.55×10−34 J⋅s, is within 1.2% of the currently defined value.[2] He also made the first determination of the Boltzmann constant from the same data and theory.[93]

Development and application

The black-body problem was revisited in 1905, when Lord Rayleigh and James Jeans (on the one hand) and Albert Einstein (on the other hand) independently proved that classical electromagnetism could never account for the observed spectrum. These proofs are commonly known as the "ultraviolet catastrophe", a name coined by Paul Ehrenfest in 1911. They contributed greatly (along with Einstein's work on the photoelectric effect) in convincing physicists that Planck's postulate of quantized energy levels was more than a mere mathematical formalism. The first Solvay Conference in 1911 was devoted to "the theory of radiation and quanta".[94]

Photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons (called "photoelectrons") from a surface when light is shone on it. It was first observed by Alexandre Edmond Becquerel in 1839, although credit is usually reserved for Heinrich Hertz,[95] who published the first thorough investigation in 1887. Another particularly thorough investigation was published by Philipp Lenard (Lénárd Fülöp) in 1902.[96] Einstein's 1905 paper[97] discussing the effect in terms of light quanta would earn him the Nobel Prize in 1921,[95] after his predictions had been confirmed by the experimental work of Robert Andrews Millikan.[98] The Nobel committee awarded the prize for his work on the photo-electric effect, rather than relativity, both because of a bias against purely theoretical physics not grounded in discovery or experiment, and dissent amongst its members as to the actual proof that relativity was real.[99][100]

Before Einstein's paper, electromagnetic radiation such as visible light was considered to behave as a wave: hence the use of the terms "frequency" and "wavelength" to characterize different types of radiation. The energy transferred by a wave in a given time is called its intensity. The light from a theatre spotlight is more intense than the light from a domestic lightbulb; that is to say that the spotlight gives out more energy per unit time and per unit space (and hence consumes more electricity) than the ordinary bulb, even though the color of the light might be very similar. Other waves, such as sound or the waves crashing against a seafront, also have their intensity. However, the energy account of the photoelectric effect didn't seem to agree with the wave description of light.

The "photoelectrons" emitted as a result of the photoelectric effect have a certain kinetic energy, which can be measured. This kinetic energy (for each photoelectron) is independent of the intensity of the light,[96] but depends linearly on the frequency;[98] and if the frequency is too low (corresponding to a photon energy that is less than the work function of the material), no photoelectrons are emitted at all, unless a plurality of photons, whose energetic sum is greater than the energy of the photoelectrons, acts virtually simultaneously (multiphoton effect).[101] Assuming the frequency is high enough to cause the photoelectric effect, a rise in intensity of the light source causes more photoelectrons to be emitted with the same kinetic energy, rather than the same number of photoelectrons to be emitted with higher kinetic energy.[96]

Einstein's explanation for these observations was that light itself is quantized; that the energy of light is not transferred continuously as in a classical wave, but only in small "packets" or quanta. The size of these "packets" of energy, which would later be named photons, was to be the same as Planck's "energy element", giving the modern version of the Planck–Einstein relation:

Einstein's postulate was later proven experimentally: the constant of proportionality between the frequency of incident light and the kinetic energy of photoelectrons was shown to be equal to the Planck constant .[98]

Atomic structure

It was John William Nicholson in 1912 who introduced h-bar into the theory of the atom which was the first quantum and nuclear atom and the first to quantize angular momentum as h/2π.[102][103][104][105][106] Niels Bohr quoted him in his 1913 paper of the Bohr model of the atom.[107] The influence of the work of Nicholson’s nuclear quantum atomic model on Bohr’s model has been written about by many historians.[108][109][106]

Niels Bohr introduced the third quantized model of the atom in 1913, in an attempt to overcome a major shortcoming of Rutherford's classical model. The first quantized model of the atom was introduced in 1910 by Arthur Erich Haas and was discussed at the 1911 Solvay conference.[102][107] In classical electrodynamics, a charge moving in a circle should radiate electromagnetic radiation. If that charge were to be an electron orbiting a nucleus, the radiation would cause it to lose energy and spiral down into the nucleus. Bohr solved this paradox with explicit reference to Planck's work: an electron in a Bohr atom could only have certain defined energies

where is the speed of light in vacuum, is an experimentally determined constant (the Rydberg constant) and . Once the electron reached the lowest energy level (), it could not get any closer to the nucleus (lower energy). This approach also allowed Bohr to account for the Rydberg formula, an empirical description of the atomic spectrum of hydrogen, and to account for the value of the Rydberg constant in terms of other fundamental constants.

Bohr also introduced the quantity , now known as the reduced Planck constant or Dirac constant, as the quantum of angular momentum. At first, Bohr thought that this was the angular momentum of each electron in an atom: this proved incorrect and, despite developments by Sommerfeld and others, an accurate description of the electron angular momentum proved beyond the Bohr model. The correct quantization rules for electrons – in which the energy reduces to the Bohr model equation in the case of the hydrogen atom – were given by Heisenberg's matrix mechanics in 1925 and the Schrödinger wave equation in 1926: the reduced Planck constant remains the fundamental quantum of angular momentum. In modern terms, if is the total angular momentum of a system with rotational invariance, and the angular momentum measured along any given direction, these quantities can only take on the values

Uncertainty principle

The Planck constant also occurs in statements of Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. Given numerous particles prepared in the same state, the uncertainty in their position, , and the uncertainty in their momentum, , obey

where the uncertainty is given as the standard deviation of the measured value from its expected value. There are several other such pairs of physically measurable conjugate variables which obey a similar rule. One example is time vs. energy. The inverse relationship between the uncertainty of the two conjugate variables forces a tradeoff in quantum experiments, as measuring one quantity more precisely results in the other quantity becoming imprecise.

In addition to some assumptions underlying the interpretation of certain values in the quantum mechanical formulation, one of the fundamental cornerstones to the entire theory lies in the commutator relationship between the position operator and the momentum operator :

where is the Kronecker delta.

Photon energy

The Planck relation connects the particular photon energy E with its associated wave frequency f:

This energy is extremely small in terms of ordinarily perceived everyday objects.

Since the frequency f, wavelength λ, and speed of light c are related by , the relation can also be expressed as

de Broglie wavelength

In 1923, Louis de Broglie generalized the Planck–Einstein relation by postulating that the Planck constant represents the proportionality between the momentum and the quantum wavelength of not just the photon, but the quantum wavelength of any particle. This was confirmed by experiments soon afterward. This holds throughout the quantum theory, including electrodynamics. The de Broglie wavelength λ of the particle is given by

where p denotes the linear momentum of a particle, such as a photon, or any other elementary particle.

The energy of a photon with angular frequency ω = 2πf is given by

while its linear momentum relates to

where k is an angular wavenumber.

These two relations are the temporal and spatial parts of the special relativistic expression using 4-vectors.

Statistical mechanics

Classical statistical mechanics requires the existence of h (but does not define its value).[110] Eventually, following upon Planck's discovery, it was speculated that physical action could not take on an arbitrary value, but instead was restricted to integer multiples of a very small quantity, the "[elementary] quantum of action", now called the Planck constant.[111][e] This was a significant conceptual part of the so-called "old quantum theory" developed by physicists including Bohr, Sommerfeld, and Ishiwara, in which particle trajectories exist but are hidden, but quantum laws constrain them based on their action. This view has been replaced by fully modern quantum theory, in which definite trajectories of motion do not even exist; rather, the particle is represented by a wavefunction spread out in space and in time. Thus there is no value of the action as classically defined. Related to this is the concept of energy quantization which existed in old quantum theory and also exists in altered form in modern quantum physics. Classical physics cannot explain either quantization of energy or the lack of classical particle motion.

In many cases, such as for monochromatic light or for atoms, quantization of energy also implies that only certain energy levels are allowed, and values in between are forbidden.[112]

Value

The Planck constant has dimensions of angular momentum. In SI units, the Planck constant is expressed with the unit joule per hertz (J⋅Hz−1) or joule-second (J⋅s).

The above values have been adopted as fixed in the 2019 redefinition of the SI base units.

Understanding the 'fixing' of the value of h

Since 2019, the numerical value of the Planck constant has been fixed, with a finite decimal representation. Under the present definition of the kilogram, which states that "The kilogram [...] is defined by taking the fixed numerical value of h to be 6.62607015×10−34 when expressed in the unit J⋅s, which is equal to kg⋅m2⋅s−1, where the metre and the second are defined in terms of speed of light c and duration of hyperfine transition of the ground state of an unperturbed caesium-133 atom ΔνCs."[113] This implies that mass metrology aims to find the value of one kilogram, and the kilogram is compensating. Every experiment aiming to measure the kilogram (such as the Kibble balance and the X-ray crystal density method), will essentially refine the value of a kilogram.

As an illustration of this, suppose the decision of making h to be exact was taken in 2010, when its measured value was 6.62606957×10−34 J⋅s, thus the present definition of kilogram was also enforced. In the future, the value of one kilogram must be refined to 6.62607015/6.62606957 ≈ 1.0000001 times the mass of the International Prototype of the Kilogram (IPK).

Significance of the value

The Planck constant is related to the quantization of light and matter. It can be seen as a subatomic-scale constant. In a unit system adapted to subatomic scales, the electronvolt is the appropriate unit of energy and the petahertz the appropriate unit of frequency. Atomic unit systems are based (in part) on the Planck constant. The physical meaning of the Planck constant could suggest some basic features of our physical world.

The Planck constant is one of the smallest constants used in physics. This reflects the fact that on a scale adapted to humans, where energies are typical of the order of kilojoules and times are typical of the order of seconds or minutes, the Planck constant is very small. One can regard the Planck constant to be only relevant to the microscopic scale instead of the macroscopic scale in our everyday experience.

Equivalently, the order of the Planck constant reflects the fact that everyday objects and systems are made of a large number of microscopic particles. For example, green light with a wavelength of 555 nanometres (a wavelength that can be perceived by the human eye to be green) has a frequency of 540 THz (540×1012 Hz). Each photon has an energy E = hf = 3.58×10−19 J. That is a very small amount of energy in terms of everyday experience, but everyday experience is not concerned with individual photons any more than with individual atoms or molecules. An amount of light more typical in everyday experience (though much larger than the smallest amount perceivable by the human eye) is the energy of one mole of photons; its energy can be computed by multiplying the photon energy by the Avogadro constant, NA = 6.02214076×1023 mol−1[114], with the result of 216 kJ, about the food energy in three apples.

Determination

In principle, the Planck constant can be determined by examining the spectrum of a black-body radiator or the kinetic energy of photoelectrons, and this is how its value was first calculated in the early twentieth century. In practice, these are no longer the most accurate methods.

Since the value of the Planck constant is fixed now, it is no longer determined or calculated in laboratories. Some of the practices given below to determine the Planck constant are now used to determine the mass of the kilogram. All of the methods given below except the X-ray crystal density method rely on the theoretical basis of the Josephson effect and the quantum Hall effect.

Josephson constant

The Josephson constant KJ relates the potential difference U generated by the Josephson effect at a "Josephson junction" with the frequency ν of the microwave radiation. The theoretical treatment of Josephson effect suggests very strongly that KJ = 2e/h.

The Josephson constant may be measured by comparing the potential difference generated by an array of Josephson junctions with a potential difference which is known in SI volts. The measurement of the potential difference in SI units is done by allowing an electrostatic force to cancel out a measurable gravitational force, in a Kibble balance. Assuming the validity of the theoretical treatment of the Josephson effect, KJ is related to the Planck constant by

Kibble balance

A Kibble balance (formerly known as a watt balance)[115] is an instrument for comparing two powers, one of which is measured in SI watts and the other of which is measured in conventional electrical units. From the definition of the conventional watt W90, this gives a measure of the product KJ2RK in SI units, where RK is the von Klitzing constant which appears in the quantum Hall effect. If the theoretical treatments of the Josephson effect and the quantum Hall effect are valid, and in particular assuming that RK = h/e2, the measurement of KJ2RK is a direct determination of the Planck constant.

Magnetic resonance

The gyromagnetic ratio γ of an object is the ratio of its magnetic moment to its angular momentum, which is directly related to the constant of proportionality between the frequency ν of nuclear magnetic resonance (or electron paramagnetic resonance for electrons) and the applied magnetic field B: ν = γB. It is difficult to measure gyromagnetic ratios precisely because of the difficulties in precisely measuring B, but the value for protons in water at 25 °C is known to an uncertainty of better than 10−6. The protons are said to be "shielded" from the applied magnetic field by the electrons in the water molecule, the same effect that gives rise to chemical shift in NMR spectroscopy, and this is indicated by a prime on the symbol for the gyromagnetic ratio, γ′p. The gyromagnetic ratio is related to the shielded proton magnetic moment μ′p, the spin number I (I = 1⁄2 for protons) and the reduced Planck constant.

The ratio of the shielded proton magnetic moment μ′p to the electron magnetic moment μe can be measured separately and to high precision, as the imprecisely known value of the applied magnetic field cancels itself out in taking the ratio. The value of μe in Bohr magnetons is also known: it is half the electron g-factor ge. Hence

A further complication is that the measurement of γ′p involves the measurement of an electric current: this is invariably measured in conventional amperes rather than in SI amperes, so a conversion factor is required. The symbol Γ′p-90 is used for the measured gyromagnetic ratio using conventional electrical units. In addition, there are two methods of measuring the value, a "low-field" method and a "high-field" method, and the conversion factors are different in the two cases. Only the high-field value Γ′p-90(hi) is of interest in determining the Planck constant.

Substitution gives the expression for the Planck constant in terms of Γ′p-90(hi):

Faraday constant

The Faraday constant F is the charge of one mole of electrons, equal to the Avogadro constant NA multiplied by the elementary charge e. It can be determined by careful electrolysis experiments, measuring the amount of silver dissolved from an electrode in a given time and for a given electric current. Substituting the definitions of NA and e gives the relation to the Planck constant.

X-ray crystal density

The X-ray crystal density method is primarily a method for determining the Avogadro constant NA, but as the Avogadro constant is related to the Planck constant, it also determines a value for h. The principle behind the method is to determine NA as the ratio between the volume of the unit cell of a crystal, measured by X-ray crystallography, and the molar volume of the substance. Crystals of silicon are used, as they are available in high quality and purity by the technology developed for the semiconductor industry. The unit cell volume is calculated from the spacing between two crystal planes referred to as d220. The molar volume Vm(Si) requires a knowledge of the density of the crystal and the atomic weight of the silicon used. The Planck constant is given by

Particle accelerator

The experimental measurement of the Planck constant in the Large Hadron Collider laboratory was carried out in 2011.

See also

- CODATA 2018

- International System of Units

- Introduction to quantum mechanics

- List of scientists whose names are used in physical constants

- Planck units

- Wave–particle duality

Notes

- ^ Some sources[16][17]: 169 [18]: 180 claim that John William Nicholson discovered the quantization of angular momentum in units of in his 1912 paper,[19] so prior to Bohr. True, Bohr does credit Nicholson for emphasizing “the possible importance of the angular momentum in the discussion of atomic systems in relation to Planck's theory.”[20]: 15 However, in his paper, Nicholson deals exclusively with the quantization of energy, not angular momentum—with the exception of one paragraph in which he says, if, therefore, the constant of Planck has, as Sommerfeld has suggested, an atomic significance, it may mean that the angular momentum of an atom can only rise or fall by discrete amounts when electrons leave or return. It is readily seen that this view presents less difficulty to the mind than the more usual interpretation, which is believed to involve an atomic constitution of energy itself,[19]: 679 and with the exception of the following text in the summary: in the present paper, the suggested theory of the coronal spectrum has been put upon a definite basis which is in accord with the recent theories of emission of energy by bodies. It is indicated that the key to the physical side of these theories lies in the fact that an expulsion or retention of an electron by any atom probably involves a discontinuous change in the angular momentum of the atom, which is dependent on the number of electrons already present.[19]: 692 The literal combination does not appear in that paper. A biographical memoir of Nicholson[21] states that Nicholson only “later” realized that the discrete changes in angular momentum are integral multiples of , but unfortunately the memoir does not say if this realization occurred before or after Bohr published his paper, or whether Nicholson ever published it.

- ^ Bohr denoted by the angular momentum of the electron around the nucleus, and wrote the quantization condition as , where is a positive integer. (See the Bohr model.)

- ^ Here are some papers that are mentioned in[18] and in which appeared without a separate symbol: [22]: 428 [23]: 549 [24]: 508 [25]: 230 [26]: 458 [27][28]: 276 [29][30][31][32].

- ^ Notable examples of such usage include Landau and Lifshitz[57]: 20 and Giffiths,[58]: 3 but there are many others, e.g.[59][60]: 449 [61]: 284 [62]: 3 [63]: 365 [64]: 14 [65]: 18 [66]: 4 [67]: 138 [68]: 251 [69]: 1 [70]: 622 [71]: xx [72]: 20 [73]: 4 [74]: 36 [75]: 41 [76]: 199 [77]: 846 [78][79][80]: 25 [81]: 653

- ^ The quantum of action, a historical name for the Planck constant, should not be confused with the quantum of angular momentum, equal to the reduced Planck constant.

References

Citations

- ^ a b "Planck constant". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-05-27. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ a b c d e f Planck, Max (1901), "Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum" (PDF), Ann. Phys., 309 (3): 553–63, Bibcode:1901AnP...309..553P, doi:10.1002/andp.19013090310, archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-06-10, retrieved 2008-12-15. English translation: "On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum". Archived from the original on 2008-04-18.". "On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- ^ "Max Planck Nobel Lecture". Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Le Système international d’unités [The International System of Units] (PDF) (in French and English) (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, 2019, p. 131, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0

- ^ a b "2018 CODATA Value: Planck constant". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- ^ "Resolutions of the 26th CGPM" (PDF). BIPM. 2018-11-16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ "2018 CODATA Value: Planck constant in eV/Hz". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ^ "2018 CODATA Value: reduced Planck constant". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-28.

- ^ "2018 CODATA Value: reduced Planck constant in eV s". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ^ a b "reduced Planck constant". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ Lyth, David H.; Liddle, Andrew R. (11 June 2009). The Primordial Density Perturbation: Cosmology, Inflation and the Origin of Structure. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-64374-0.

- ^ Huang, Kerson (26 April 2010). Quantum Field Theory: From Operators to Path Integrals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-40846-7.

- ^ Schmitz, Kenneth S. (11 November 2016). Physical Chemistry: Concepts and Theory. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-800600-9.

- ^ Chabay, Ruth W.; Sherwood, Bruce A. (20 November 2017). Matter and Interactions. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-45575-2.

- ^ Schwarz, Patricia M.; Schwarz, John H. (25 March 2004). Special Relativity: From Einstein to Strings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44950-2.

- ^ Heilbron, John L. (June 2013). "The path to the quantum atom". Nature. 498 (7452): 27–30. doi:10.1038/498027a. PMID 23739408. S2CID 4355108.

- ^ McCormmach, Russell (1 January 1966). "The atomic theory of John William Nicholson". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 3 (2): 160–184. doi:10.1007/BF00357268. JSTOR 41133258. S2CID 120797894.

- ^ a b Mehra, Jagdish; Rechenberg, Helmut (3 August 1982). The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. Vol. 1. Springer New York. ISBN 978-0-387-90642-3.

- ^ a b c Nicholson, J. W. (14 June 1912). "The Constitution of the Solar Corona. II". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 72 (8). Oxford University Press: 677–693. doi:10.1093/mnras/72.8.677. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b Bohr, N. (July 1913). "I. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (151): 1–25. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955.

- ^ Wilson, W. (1956). "John William Nicholson 1881-1955". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 2: 209–214. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1956.0014. JSTOR 769485.

- ^ Sommerfeld, A. (1915). "Zur Theorie der Balmerschen Serie" (PDF). Sitzungsberichte der mathematisch-physikalischen Klasse der K. B. Akademie der Wissenschaften zu München. 33 (198): 425–458. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2013-40053-8.

- ^ Schwarzschild, K. (1916). "Zur Quantenhypothese". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin: 548–568.

- ^ Ehrenfest, P. (June 1917). "XLVIII. Adiabatic invariants and the theory of quanta". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 33 (198): 500–513. doi:10.1080/14786440608635664.

- ^ Landé, A. (June 1919). "Das Serienspektrum des Heliums". Physikalische Zeitschrift. 20: 228–234.

- ^ Bohr, N. (October 1920). "Über die Serienspektra der Elemente". Zeitschrift für Physik. 2 (5): 423–469. doi:10.1007/BF01329978.

- ^ Stern, Otto (December 1921). "Ein Weg zur experimentellen Prüfung der Richtungsquantelung im Magnetfeld". Zeitschrift für Physik. 7 (1): 249–253. doi:10.1007/BF01332793.

- ^ Heisenberg, Werner (December 1922). "Zur Quantentheorie der Linienstruktur und der anomalen Zeemaneflekte". Zeitschrift für Physik. 8 (1): 273–297. doi:10.1007/BF01329602.

- ^ Kramers, H. A.; Pauli, W. (December 1923). "Zur Theorie der Bandenspektren". Zeitschrift für Physik. 13 (1): 351–367. doi:10.1007/BF01328226.

- ^ Born, M.; Jordan, P. (December 1925). "Zur Quantenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik. 34 (1): 858–888. doi:10.1007/BF01328531.

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (December 1925). "The fundamental equations of quantum mechanics". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 109 (752): 642–653. doi:10.1098/rspa.1925.0150.

- ^ Born, M.; Heisenberg, W.; Jordan, P. (August 1926). "Zur Quantenmechanik. II". Zeitschrift für Physik. 35 (8–9): 557–615. doi:10.1007/BF01379806.

- ^ Schrödinger, E. (1926). "Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem". Annalen der Physik. 384 (4): 361–376. doi:10.1002/andp.19263840404.

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (October 1926). "On the theory of quantum mechanics". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 112 (762): 661–677. doi:10.1098/rspa.1926.0133.

- ^ a b Mehra, Jagdish; Rechenberg, Helmut (2000). The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. Vol. 6. New York: Springer.

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (1930). The Principles of Quantum Mechanics (1st ed.). Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon.

- ^ a b Rennie, Richard; Law, Jonathan, eds. (2017). "Planck constant". A Dictionary of Physics. Oxford Quick Reference (7th ed.). Oxford,UK: OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0198821472.

- ^ The International Encyclopedia of Physical Chemistry and Chemical Physics. Pergamon Press. 1960.

- ^ Vértes, Attila; Nagy, Sándor; Klencsár, Zoltán; Lovas, Rezso György; Rösch, Frank (10 December 2010). Handbook of Nuclear Chemistry. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-0719-6.

- ^ Bethe, Hans A.; Salpeter, Edwin E. (1957). "Quantum Mechanics of One- and Two-Electron Atoms". In Flügge, Siegfried (ed.). Handbuch der Physik: Atome I-II. Springer.

- ^ Lang, Kenneth (11 November 2013). Astrophysical Formulae: A Compendium for the Physicist and Astrophysicist. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-11188-8.

- ^ Galgani, L.; Carati, A.; Pozzi, B. (December 2002). "The Problem of the Rate of Thermalization, and the Relations between Classical and Quantum Mechanics". In Fabrizio, Mauro; Morro, Angelo (eds.). Mathematical Models and Methods for Smart Materials, Cortona, Italy, 25 – 29 June 2001. pp. 111–122. doi:10.1142/9789812776273_0011.

- ^ Fox, Mark (14 June 2018). A Student's Guide to Atomic Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-99309-5.

- ^ Kleiss, Ronald (10 June 2021). Quantum Field Theory: A Diagrammatic Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-78750-5.

- ^ Zohuri, Bahman (5 January 2021). Thermal Effects of High Power Laser Energy on Materials. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-63064-5.

- ^ Balian, Roger (26 June 2007). From Microphysics to Macrophysics: Methods and Applications of Statistical Physics. Volume II. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-45480-9.

- ^ Chen, C. Julian (15 August 2011). Physics of Solar Energy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-04459-9.

- ^ "Dirac h". Britannica. Archived from the original on 2023-02-17. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ Shoenberg, D. (3 September 2009). Magnetic Oscillations in Metals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-58317-3.

- ^ Powell, John L.; Crasemann, Bernd (5 May 2015). Quantum Mechanics. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-80478-1.

- ^ Dresden, Max (6 December 2012). H.A. Kramers Between Tradition and Revolution. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-4622-0.

- ^ Johnson, R. E. (6 December 2012). Introduction to Atomic and Molecular Collisions. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4684-8448-9.

- ^ Garcia, Alejandro; Henley, Ernest M. (13 July 2007). Subatomic Physics (3rd Edition). World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-981-310-167-8.

- ^ Holbrow, Charles H.; Lloyd, James N.; Amato, Joseph C.; Galvez, Enrique; Parks, M. Elizabeth (14 September 2010). Modern Introductory Physics. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-79080-0.

- ^ Polyanin, Andrei D.; Chernoutsan, Alexei (18 October 2010). A Concise Handbook of Mathematics, Physics, and Engineering Sciences. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-0640-1.

- ^ Dowling, Jonathan P. (24 August 2020). Schrödinger’s Web: Race to Build the Quantum Internet. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-000-08017-9.

- ^ Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (22 October 2013). Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-4912-7.

- ^ Griffiths, David J.; Schroeter, Darrell F. (20 November 2019). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-10314-5.

- ^ "Planck's constant". The Great Soviet Encyclopedia (1970-1979, 3rd ed.). The Gale Group.

- ^ Itzykson, Claude; Zuber, Jean-Bernard (20 September 2012). Quantum Field Theory. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-13469-7.

- ^ Kaku, Michio (1993). Quantum Field Theory: A Modern Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507652-3.

- ^ Bogoli︠u︡bov, Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich; Shirkov, Dmitriĭ Vasilʹevich (1982). Quantum Fields. Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Advanced Book Program/World Science Division. ISBN 978-0-8053-0983-6.

- ^ Aitchison, Ian J. R.; Hey, Anthony J. G. (17 December 2012). Gauge Theories in Particle Physics: A Practical Introduction: From Relativistic Quantum Mechanics to QED, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-1299-3.

- ^ de Wit, B.; Smith, J. (2 December 2012). Field Theory in Particle Physics, Volume 1. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-59622-2.

- ^ Brown, Lowell S. (1992). Quantum Field Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46946-3.

- ^ Buchbinder, Iosif L.; Shapiro, Ilya (March 2021). Introduction to Quantum Field Theory with Applications to Quantum Gravity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-883831-9.

- ^ Jaffe, Arthur (25 March 2004). "9. Where does quantum field theory fit into the big picture?". In Cao, Tian Yu (ed.). Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Field Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60272-3.

- ^ Cabibbo, Nicola; Maiani, Luciano; Benhar, Omar (28 July 2017). An Introduction to Gauge Theories. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4987-3452-3.

- ^ Casalbuoni, Roberto (6 April 2017). Introduction To Quantum Field Theory (Second Edition). World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-981-314-668-6.

- ^ Das, Ashok (24 July 2020). Lectures On Quantum Field Theory (2nd ed.). World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-12-2088-3.

- ^ Desai, Bipin R. (2010). Quantum Mechanics with Basic Field Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87760-2.

- ^ Donoghue, John; Sorbo, Lorenzo (8 March 2022). A Prelude to Quantum Field Theory. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-22348-3.

- ^ Folland, Gerald B. (3 February 2021). Quantum Field Theory: A Tourist Guide for Mathematicians. American Mathematical Soc. ISBN 978-1-4704-6483-7.

- ^ Fradkin, Eduardo (23 March 2021). Quantum Field Theory: An Integrated Approach. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14908-0.

- ^ Gelis, François (11 July 2019). Quantum Field Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-48090-1.

- ^ Greiner, Walter; Reinhardt, Joachim (9 March 2013). Quantum Electrodynamics. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-05246-4.

- ^ Liboff, Richard L. (2003). Introductory Quantum Mechanics (4th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-0441-7.

- ^ Barut, A. O. (1 August 1978). "The Creation of a Photon: A Heuristic Calculation of Planck's Constant ħ or the Fine Structure Constant α". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A. 33 (8): 993–994. Bibcode:1978ZNatA..33..993B. doi:10.1515/zna-1978-0819. S2CID 45829793.

- ^ Kocia, Lucas; Love, Peter (12 July 2018). "Measurement contextuality and Planck's constant". New Journal of Physics. 20 (7): 073020. arXiv:1711.08066. Bibcode:2018NJPh...20g3020K. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/aacef2. S2CID 73623448.

- ^ Humpherys, David (28 November 2022). "The Implicit Structure of Planck's Constant". European Journal of Applied Physics. 4 (6): 22–25. doi:10.24018/ejphysics.2022.4.6.227. S2CID 254359279.

- ^ Bais, F. Alexander; Farmer, J. Doyne (2008). "The Physics of Information". In Adriaans, Pieter; van Benthem, Johan (eds.). Philosophy of Information. Handbook of the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 8. Amsterdam: North-Holland. arXiv:0708.2837. ISBN 978-0-444-51726-5.

- ^ Hirota, E.; Sakakima, H.; Inomata, K. (9 March 2013). Giant Magneto-Resistance Devices. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-04777-4.

- ^ Gardner, John H. (1988). "An Invariance Theory". Encyclia. 65: 139.

- ^ Levine, Raphael D. (4 June 2009). Molecular Reaction Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44287-9.

- ^ a b Bitter, Francis; Medicus, Heinrich A. (1973). Fields and particles. New York: Elsevier. pp. 137–144.

- ^ Boya, Luis J. (2004). "The Thermal Radiation Formula of Planck (1900)". arXiv:physics/0402064v1.

- ^ Planck, M. (1914). The Theory of Heat Radiation. Masius, M. (transl.) (2nd ed.). P. Blakiston's Son. pp. 6, 168. OL 7154661M.

- ^ Chandrasekhar, S. (1960) [1950]. Radiative Transfer (Revised reprint ed.). Dover. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-486-60590-6.

- ^ Rybicki, G. B.; Lightman, A. P. (1979). Radiative Processes in Astrophysics. Wiley. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-471-82759-7. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- ^ Shao, Gaofeng; et al. (2019). "Improved oxidation resistance of high emissivity coatings on fibrous ceramic for reusable space systems". Corrosion Science. 146: 233–246. arXiv:1902.03943. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2018.11.006. S2CID 118927116.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (1 December 2000), Max Planck: the reluctant revolutionary, PhysicsWorld.com, archived from the original on 2009-01-08

- ^ Kragh, Helge (1999), Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, p. 62, ISBN 978-0-691-09552-3, archived from the original on 2021-12-06, retrieved 2021-10-31

- ^ Planck, Max (2 June 1920), The Genesis and Present State of Development of the Quantum Theory (Nobel Lecture), archived from the original on 15 July 2011, retrieved 13 December 2008

- ^ Previous Solvay Conferences on Physics, International Solvay Institutes, archived from the original on 16 December 2008, retrieved 12 December 2008

- ^ a b See, e.g., Arrhenius, Svante (10 December 1922), Presentation speech of the 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics, archived from the original on 4 September 2011, retrieved 13 December 2008

- ^ a b c Lenard, P. (1902), "Ueber die lichtelektrische Wirkung", Annalen der Physik, 313 (5): 149–98, Bibcode:1902AnP...313..149L, doi:10.1002/andp.19023130510, archived from the original on 2019-08-18, retrieved 2019-07-03

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1905), "Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt" (PDF), Annalen der Physik, 17 (6): 132–48, Bibcode:1905AnP...322..132E, doi:10.1002/andp.19053220607, archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-09, retrieved 2009-12-03

- ^ a b c Millikan, R. A. (1916), "A Direct Photoelectric Determination of Planck's h", Physical Review, 7 (3): 355–88, Bibcode:1916PhRv....7..355M, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.7.355

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2007-04-10), Einstein: His Life and Universe, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4165-3932-2, archived from the original on 2020-01-09, retrieved 2021-10-31, pp. 309–314.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2018-07-03. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ^ *Smith, Richard (1962). "Two Photon Photoelectric Effect". Physical Review. 128 (5): 2225. Bibcode:1962PhRv..128.2225S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.128.2225.

- Smith, Richard (1963). "Two-Photon Photoelectric Effect". Physical Review. 130 (6): 2599. Bibcode:1963PhRv..130.2599S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.130.2599.4.

- ^ a b Heilbron, John L. (2013). "The path to the quantum atom". Nature. 498 (7452): 27–30. doi:10.1038/498027a. PMID 23739408. S2CID 4355108.

- ^ Nicholson, J. W. (1911). "The spectrum of Nebulium". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 72: 49. Bibcode:1911MNRAS..72...49N. doi:10.1093/mnras/72.1.49.

- ^ *Nicholson, J. W. (1911). "The Constitution of the Solar Corona I". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 72: 139. Bibcode:1911MNRAS..72..139N. doi:10.1093/mnras/72.2.139.

- Nicholson, J. W. (1912). "The Constitution of the Solar Corona II". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 72 (8): 677–693. doi:10.1093/mnras/72.8.677.

- Nicholson, J. W. (1912). "The Constitution of the Solar Corona III". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 72 (9): 729–740. doi:10.1093/mnras/72.9.729.

- ^ Nicholson, J. W. (1912). "On the new nebular line at λ4353". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 72 (8): 693. Bibcode:1912MNRAS..72..693N. doi:10.1093/mnras/72.8.693.

- ^ a b McCormmach, Russell (1966). "The Atomic Theory of John William Nicholson". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 3 (2): 160–184. doi:10.1007/BF00357268. JSTOR 41133258. S2CID 120797894.

- ^ a b Bohr, N. (1913). "On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 6th series. 26 (151): 1–25. Bibcode:1913PMag...26..476B. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ Hirosige, Tetu; Nisio, Sigeko (1964). "Formation of Bohr's theory of atomic constitution". Japanese Studies in History of Science. 3: 6–28.

- ^ J. L. Heilbron, A History of Atomic Models from the Discovery of the Electron to the Beginnings of Quantum Mechanics, diss. (University of California, Berkeley, 1964).

- ^ Giuseppe Morandi; F. Napoli; E. Ercolessi (2001), Statistical mechanics: an intermediate course, World Scientific, p. 84, ISBN 978-981-02-4477-4, archived from the original on 2021-12-06, retrieved 2021-10-31

- ^ ter Haar, D. (1967). The Old Quantum Theory. Pergamon Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-08-012101-7.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (2003), "Physics and Reality" (PDF), Daedalus, 132 (4): 24, doi:10.1162/001152603771338742, S2CID 57559543, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-15,

The question is first: How can one assign a discrete succession of energy values Hσ to a system specified in the sense of classical mechanics (the energy function is a given function of the coordinates qr and the corresponding momenta pr)? The Planck constant h relates the frequency Hσ/h to the energy values Hσ. It is therefore sufficient to give to the system a succession of discrete frequency values.

- ^ Le Système international d’unités [The International System of Units] (PDF) (in French and English) (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, 2019, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0

- ^ "2018 CODATA Value: Avogadro constant". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ Materese, Robin (2018-05-14). "Kilogram: The Kibble Balance". NIST. Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

Sources

External links

- "The role of the Planck constant in physics" – presentation at 26th CGPM meeting at Versailles, France, November 2018 when voting took place.

- “The Planck constant and its units” – presentation at the 35th Symposium on Chemical Physics at the University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, November 3 2019.

![{\displaystyle [{\hat {p}}_{i},{\hat {x}}_{j}]=-i\hbar \delta _{ij},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a6de152aa445b7ca6653b9dd087ad604c2b8bf0e)