Bornean orangutan: Difference between revisions

StevenBjerke (talk | contribs) |

Annielogue (talk | contribs) →Conservation status: used original report rather than newspaper: more detail could be added. |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

The Bornean orangutan is [[Endangered species|endangered]]<ref name=IUCN/> according to the [[IUCN Red List]] of [[mammal]]s, and is listed on Appendix I of [[CITES]]. The total number of Bornean orangutans is estimated to be less than 14 percent of what it was in the recent past (from around 10,000 years ago until the middle of the twentieth century) and this sharp decline has occurred mostly over the past few decades due to human activities and development.<ref name=IUCN/> Species distribution is now highly patchy throughout Borneo: it is apparently absent or uncommon in the south-east of the island, as well as in the forests between the [[Rejang River]] in central [[Sarawak]] and the Padas River in western [[Sabah]] (including the Sultanate of [[Brunei]]).<ref name=IUCN/> There is a population of around 6,900 in [[Sabangau National Park]], but this environment is at risk.<ref>[http://www.wildcru.org/aboutus/people/cheyne_pdfs/Cheyne%20Gibbon%20Density%202007.pdf Density and population estimate of gibbons (''Hylobates albibarbis'') in the Sabangau catchment, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia].{{Dead link|date=March 2011}}</ref> According to an anthropologist at Harvard University, it is expected that in 10 to 20 years orangutans will be [[extinct]] in the wild if there is no serious effort to overcome the threats that they are facing.<ref name="Mayell2004">{{cite web | author = Mayell, H. | url = http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/09/0930_030930_orangutanthreat.html | publisher = National Geographic | title = Wild Orangutans: Extinct by 2023? | date = 2004-03-09 | accessdate = 2011-03-03}}</ref> |

The Bornean orangutan is [[Endangered species|endangered]]<ref name=IUCN/> according to the [[IUCN Red List]] of [[mammal]]s, and is listed on Appendix I of [[CITES]]. The total number of Bornean orangutans is estimated to be less than 14 percent of what it was in the recent past (from around 10,000 years ago until the middle of the twentieth century) and this sharp decline has occurred mostly over the past few decades due to human activities and development.<ref name=IUCN/> Species distribution is now highly patchy throughout Borneo: it is apparently absent or uncommon in the south-east of the island, as well as in the forests between the [[Rejang River]] in central [[Sarawak]] and the Padas River in western [[Sabah]] (including the Sultanate of [[Brunei]]).<ref name=IUCN/> There is a population of around 6,900 in [[Sabangau National Park]], but this environment is at risk.<ref>[http://www.wildcru.org/aboutus/people/cheyne_pdfs/Cheyne%20Gibbon%20Density%202007.pdf Density and population estimate of gibbons (''Hylobates albibarbis'') in the Sabangau catchment, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia].{{Dead link|date=March 2011}}</ref> According to an anthropologist at Harvard University, it is expected that in 10 to 20 years orangutans will be [[extinct]] in the wild if there is no serious effort to overcome the threats that they are facing.<ref name="Mayell2004">{{cite web | author = Mayell, H. | url = http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/09/0930_030930_orangutanthreat.html | publisher = National Geographic | title = Wild Orangutans: Extinct by 2023? | date = 2004-03-09 | accessdate = 2011-03-03}}</ref> |

||

This view is also supported by the [[United Nations Environment Programme]], which |

This view is also supported by the [[United Nations Environment Programme]], which stated in its 2007 report that due to [[illegal logging]], [[peat bog fire|fire]] and the extensive development of [[oil palm]] plantations, orangutans are endangered, and if the current trend continues, they will become extinct.<ref name="UN2007">{{cite report | author = Nellemann, C., Miles, L., Kaltenborn, B.P., Virtue, M. & Ahlenius, H. | year = 2007 | title = The last stand of the orangutan – State of emergency: Illegal logging, fire and palm oil in Indonesia’s national parks | publisher = United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal | location = Norway | year = 2007 | url = http://www.unep.org/grasp/docs/2007Jan-LastStand-of-Orangutan-report.pdf | format = pdf | accessdate = 2011-03-03}}</ref> |

||

A November 2011 survey, based on interviews with 6,983 respondents in 687 villages across Kalimantan in 2008 to 2009, gave estimated orangutan killing rates of between 750 and 1800 in the year leading up to April 2008.<ref name=meijaard>{{cite journal|last=Meijaard|first=Erik|coauthors=Buchori, Damayanti, Hadiprakarsa, Yokyok, Utami-Atmoko, Sri Suci, Nurcahyo, Anton, Tjiu, Albertus, Prasetyo, Didik, Nardiyono, , Christie, Lenny, Ancrenaz, Marc, Abadi, Firman, Antoni, I Nyoman Gede, Armayadi, Dedy, Dinato, Adi, Ella, , Gumelar, Pajar, Indrawan, Tito P., Kussaritano, , Munajat, Cecep, Priyono, C. Wawan Puji, Purwanto, Yadi, Puspitasari, Dewi, Putra, M. Syukur Wahyu, Rahmat, Abdi, Ramadani, Harri, Sammy, Jim, Siswanto, Dedi, Syamsuri, Muhammad, Andayani, Noviar, Wu, Huanhuan, Wells, Jessie Anne, Mengersen, Kerrie, Turvey, Samuel T.|title=Quantifying Killing of Orangutans and Human-Orangutan Conflict in Kalimantan, Indonesia|journal=PLoS ONE|date=11 November 2011|volume=6|issue=11|pages=e27491|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0027491|url=http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0027491|accessdate=27 November 2011}}</ref> These killing rates were higher than previously thought and confirm that, the continued existence of the orangutan in Kalimantan, is under serious threat. The survey did not quantify the additional threat to the species of habitat loss due to deforestation and expanding palm-oil plantations. |

|||

Based on survey to 6,972 respondents in 698 villages across [[Kalimantan]] in 2008 to 2009, they found 691 orangutan were slaughtered, most of whom were eaten by residents for several reasons such as:<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2011/11/02/orangutans-killed-meat-kalimantan.html |title=Orangutans killed for meat in Kalimantan |date=November 2, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* Desperate and had no other choice after spending 3 days hunting for food |

|||

* To make traditional medicine |

|||

* Want to sell the surviving orangutan babies, but should kill the mother first. |

|||

In November 2011, 2 men |

In November 2011, 2 men were arrested for killing at least 20 orangutans and a number of long-nosed [[proboscis monkey]]s. They were ordered to conduct the killings by the supervisor of a palm oil plantantion, to protect the crop, with a payment of $100 for a dead orangutan and $22 for a monkey.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://english.kompas.com/read/2011/11/24/13304328/Mass.Slaughter.of.Orang-utans.and.Monkeys.is.Continuing.in.Kalimantan |title=Mass Slaughter of Orang-utans and Monkeys is Continuing in Kalimantan |date=November 24, 2011}}</ref> |

||

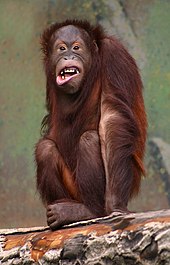

[[File:Kepin - Kevin taking a nap.jpg|left|thumb|A young rescued orangutan at Nyaru Menteng takes a nap.]] |

[[File:Kepin - Kevin taking a nap.jpg|left|thumb|A young rescued orangutan at Nyaru Menteng takes a nap.]] |

||

Revision as of 09:32, 27 November 2011

| Bornean orangutan[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. pygmaeus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pongo pygmaeus (Linnaeus, 1760)

| |

| |

| Distribution in Indonesia | |

The Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus, is a species of orangutan native to the island of Borneo. Together with the slightly smaller Sumatran orangutan, it belongs to the only genus of great apes native to Asia.

The Bornean orangutan has a life span of up to 35 years in the wild; in captivity it can live to be 60.[3] A survey of wild orangutans found that males weigh on average 75 kilograms (165 lb), ranging from 50–100 kilograms (110–220 lb), and 1.2–1.4 metres (3.9–4.6 ft) long; females average 38.5 kilograms (85 lb), ranging from 30–50 kilograms (66–110 lb), and 1–1.2 metres (3.3–3.9 ft) long.[4][5]

Taxonomy

The Bornean orangutan and the Sumatran orangutan diverged about 400,000 years ago,[6] well before Borneo and Sumatra separated.[citation needed] There has been a continued low level of gene flow between them since then.[6] The two orangutan species were considered merely subspecies until 1996, following sequencing of their mitochondrial DNA.

The Bornean orangutan has three subspecies:[1][2]

- Northwest Bornean orangutan P. p. pygmaeus - Sarawak (Malaysia) & northern West Kalimantan (Indonesia)

- Central Bornean orangutan P. p. wurmbii - Southern West Kalimantan & Central Kalimantan (Indonesia)

- Northeast Bornean orangutan P. p. morio - East Kalimantan (Indonesia) & Sabah (Malaysia)

There is some uncertainty about this, however. The population currently listed as P. p. wurmbii may be closer to the Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii) than to the Bornean orangutan. If this is confirmed, abelii would be a subspecies of P. wurmbii (Tiedeman, 1808).[7] In addition, the type locality of pygmaeus has not been established beyond doubt; it may be from the population currently listed as wurmbii (in which case wurmbii would be a junior synonym of pygmaeus, while one of the names currently considered a junior synonym of pygmaeus would take precedence for the taxon in Sarawak and northern West Kalimantan).[7] Bradon-Jones et al considered morio to be a synonym of pygmaeus and the population found in East Kalimantan and Sabah to be a potentially unnamed separate taxon.[7]

Description

The Bornean orangutan has a distinctive body shape with very long arms that may reach up to two metres in length. They have a coarse, shaggy reddish coat[8] and grasping hands and feet.[9] They are highly sexually dimorphic, with adult males being distinguished by their large size, throat pouch and flanges on either side of the face, known as cheek pads.[10]

Ecology

The Bornean orangutan lives in tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests in the Bornean lowlands as well as mountainous areas 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) in elevation. It lives at different heights in the trees and moves large distances to find trees bearing fruit.

The Bornean orangutan travels on the ground more than its Sumatran counterpart. It is theorized this may be in part because there is no need to avoid the large predators which only exist in Sumatra such as the Sumatran Tiger.[11]

Behavior and biology

The Bornean orangutan is more solitary than the Sumatran orangutan. Two or three orangutans that have overlapping territories may only interact for short periods of time.[12] They are the largest arboreal mammal and spend almost all of their time in the trees, clambering between branches or using their body weight to bend and sway trees.[9] Each night a nest is built from bent branches, high up in the trees.[5]

Diet

The Bornean orangutan diet is composed of over 400 types of food, including wild figs, durians,[10] leaves, seeds, bird egg, and bark.[5] It also eats insects but to a lesser extent than the Sumatran orangutan. Bornean orangutans have been sighted using spears to catch fish.[13]

Reproduction

Males and females generally only come together to mate.[12] Sub-adult males (unflanged) will try to mate with any female and will be successful around half the time.[12] Dominant flanged males will call and advertise their position to receptive females, who prefer mating with flanged males.[12]

The Bornean orangutan are the slowest breeding of all mammal species, with an inter-birth interval of approximately eight years.[10] They are long-lived and females tend to only give birth after they reach 15 years of age. Newborn orangutans nurse every three to four hours, and begin to take soft food from their mothers' lips by four months. During the first year of its life, the young clings to its mother's abdomen by entwining its fingers in and gripping her fur. Offspring are weaned at four years, and at around five years they start their adolescent stage.[12] During this period they will actively seek other young orangutans to play with and travel with.[12]

Conservation status

The Bornean orangutan is more common than the Sumatran, with about 54,500 individuals in the wild; there are only about 6,600 Sumatran orangutans left in the wild.[14] Orangutans are becoming increasingly endangered due to habitat destruction and the bushmeat trade, and young orangutans are captured to be sold as pets, usually entailing the killing of their mothers.[15]

The Bornean orangutan is endangered[2] according to the IUCN Red List of mammals, and is listed on Appendix I of CITES. The total number of Bornean orangutans is estimated to be less than 14 percent of what it was in the recent past (from around 10,000 years ago until the middle of the twentieth century) and this sharp decline has occurred mostly over the past few decades due to human activities and development.[2] Species distribution is now highly patchy throughout Borneo: it is apparently absent or uncommon in the south-east of the island, as well as in the forests between the Rejang River in central Sarawak and the Padas River in western Sabah (including the Sultanate of Brunei).[2] There is a population of around 6,900 in Sabangau National Park, but this environment is at risk.[16] According to an anthropologist at Harvard University, it is expected that in 10 to 20 years orangutans will be extinct in the wild if there is no serious effort to overcome the threats that they are facing.[17]

This view is also supported by the United Nations Environment Programme, which stated in its 2007 report that due to illegal logging, fire and the extensive development of oil palm plantations, orangutans are endangered, and if the current trend continues, they will become extinct.[18]

A November 2011 survey, based on interviews with 6,983 respondents in 687 villages across Kalimantan in 2008 to 2009, gave estimated orangutan killing rates of between 750 and 1800 in the year leading up to April 2008.[19] These killing rates were higher than previously thought and confirm that, the continued existence of the orangutan in Kalimantan, is under serious threat. The survey did not quantify the additional threat to the species of habitat loss due to deforestation and expanding palm-oil plantations.

In November 2011, 2 men were arrested for killing at least 20 orangutans and a number of long-nosed proboscis monkeys. They were ordered to conduct the killings by the supervisor of a palm oil plantantion, to protect the crop, with a payment of $100 for a dead orangutan and $22 for a monkey.[20]

Rescue and rehabilitation centres

A number of orangutan rescue and rehabilitation projects operate in Borneo.

The Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (BOS) founded by Dr Willie Smits has rescue and rehabilitation centres at Wanariset and Samboja Lestari in East Kalimantan and Nyaru Menteng, in Central Kalimantan founded and managed by Lone Drøscher Nielsen. BOS also works to conserve and recreate the fast disappearing rainforest habitat of the orangutan, at Samboja Lestari and Mawas.

Orangutan Foundation International, founded by Dr Birutė Galdikas, rescues and rehabilitates orangutans, preparing them for release back into protected areas of the Indonesian rain forest. In addition, OFI promotes the preservation of the rain forest for the orangutans.

The Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre near Sandakan in the state of Sabah in Malaysian Borneo opened in 1964 as the first official orangutan rehabilitation project.[21]

See also

References

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Bornean orangutan" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

- ^ a b Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e Template:IUCN2008

- ^ "Primates: Orangutans". Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ^ Wood, G. (1977). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. New York: Sterling Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ a b c Ciszek, D.; Schommer, M.K. (2009-06-28). "ADW: Pongo pygmaeus: Information". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ^ a b Locke, Devin P. (2011-01-26). "Comparative and demographic analysis of orang-utan genomes". Nature. 469 (7331): 529–533. doi:10.1038/nature09687. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Bradon-Jones, D.; Eudey, A.A.; Geissmann, T.; Groves, C.P.; Melnick, D.J.; Morales, J.C.; Shekelle, M.; Stewart, C.B. (2004). "Asian primate classification" (pdf). International Journal of Primatology. 23 (1): 97–164. doi:10.1023/B:IJOP.0000014647.18720.32. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ Burnie, D. (2001). Animal. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- ^ a b Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c Lorenz, M. (2004). Pers. comm.

- ^ Cawthon Lang, K.A. (2005). "Primate Factsheets: Orangutan (Pongo) Taxonomy, Morphology, & Ecology". Primate Info Net. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- ^ a b c d e f Cawthon Lang, K.A. (2005). "Primate Factsheets: Orangutan (Pongo) Behavior". Primate Info Net. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ Bleiman, B. (2008-04-29). "Orangutan "Spear Fishes"". Zooillogix. ScienceBlogs. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ^ Orangutan Action Plan 2007-2017 (pdf) (Report) (in Indonesian). Government of Indonesia. 2007. p. 5. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

{{cite report}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help) - ^ Cawthon Lang, K.A. (2005). "Primate Factsheets: Orangutan (Pongo) Conservation". Primate Info Net. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ Density and population estimate of gibbons (Hylobates albibarbis) in the Sabangau catchment, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia.[dead link]

- ^ Mayell, H. (2004-03-09). "Wild Orangutans: Extinct by 2023?". National Geographic. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ^ Nellemann, C., Miles, L., Kaltenborn, B.P., Virtue, M. & Ahlenius, H. (2007). The last stand of the orangutan – State of emergency: Illegal logging, fire and palm oil in Indonesia’s national parks (pdf) (Report). Norway: United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

{{cite report}}: soft hyphen character in|publisher=at position 50 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meijaard, Erik (11 November 2011). "Quantifying Killing of Orangutans and Human-Orangutan Conflict in Kalimantan, Indonesia". PLoS ONE. 6 (11): e27491. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027491. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Mass Slaughter of Orang-utans and Monkeys is Continuing in Kalimantan". November 24, 2011.

- ^ Thompson, S. (2010). The Intimate Ape: Orangutans and the Secret Life of a Vanishing Species. Citadel Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0806531335.

External links

![]() Media related to Pongo pygmaeus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pongo pygmaeus at Wikimedia Commons