Aluminium hydride

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Aluminium hydride | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Alumane | |

| Other names

Alane

Aluminic hydride | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.139 |

| 245 | |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| AlH3 | |

| Molar mass | 29.99 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline solid, non-volatile, highly polymerized, needle-like crystals |

| Density | 1.486 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 150 °C |

| Boiling point | Decomposition |

| Reactive | |

| Related compounds | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Aluminium hydride is an inorganic compound with the formula AlH3. It is a colourless solid that is pyrophoric. Although rarely encountered outside of research laboratory, alane and its derivatives are used as reducing agents in organic synthesis.[1]

Structure

Alane is a polymer. Its formula is sometimes represented with the formula (AlH3)n. Aluminium hydride forms numerous polymorphs, which are named α-alane, α’-alane, β-alane, δ-alane, ε-alane, θ-alane, and γ-alane. α-Alane has a cubic or rhombohedral morphology, whereas α’-alane forms needle like crystals and γ-alane forms a bundle of fused needles. Alane is soluble in THF and ether, and its precipitation rate from ether depends on the preparation method.[2]

The structure of α-alane has been determined and features aluminium atoms surrounded by 6 hydrogen atoms that bridge to 6 other aluminium atoms. The Al-H distances are all equivalent (172pm) and the Al-H-Al angle is 141°.[3]

|

|

|

α-Alane is the most thermally stable polymorph. β-alane and γ-alane are produced together, and convert to α-alane upon heating. δ, ε, and θ-alane are produced in different crystallization condition. Although they are less thermally stable, they do not convert into α-alane upon heating.[2]

Molecular forms of alane

Monomeric AlH3 has been isolated at low temperature in a solid noble gas matrix and shown to be planar.[4] The dimer Al2H6 has been isolated in solid hydrogen and is isostructural with diborane,B2H6, and digallane, Ga2H6.[5][6]

Preparation

Aluminium hydride impurities and related amines and ether complexes have long been reported.[7] Its first synthesis published in 1947 and a U.S. patent for the synthesis was assigned to Petrie et al. in 1999.[8][9] Aluminium hydride is prepared by treating lithium aluminium hydride with aluminium trichloride.[10] The procedure is intricate, attention must be given to the removal of lithium chloride.

- 3 LiAlH4 + AlCl3 → 4 AlH3 + 3 LiCl

The ether solution of alane requires immediate use, because polymeric material precipitate otherwise. Aluminium hydride solutions are known to degrade after 3 days. Aluminium hydride is more reactive than LiAlH4, but their handling properties are similar.[2]

Several other methods exist for the preparation of aluminium hydride:

- 2 LiAlH4 + BeCl2 → 2 AlH3 + Li2BeH2Cl2

- 2 LiAlH4 + H2SO4 → 2 AlH3 + Li2SO4 + 2 H2

- 2 LiAlH4 + ZnCl2 → 2 AlH3 + 2 LiCl + ZnH2

Electrochemical synthesis

Alane can be produced electrochemically.[11][12][13][14] As described in the 1962 patent, the method avoids chloride impurities. Two possible mechanisms are discussed for the formation of alane in Clasen's electrochemical cell containing THF as the solvent, sodium aluminium hydride as the electrolyte, an aluminium anode, and an iron (Fe) wire submerged in mercury (Hg) as the cathode. The sodium forms an amalgam with the Hg cathode preventing side reactions and the hydrogen produced in the first reaction could be captured and reacted back with the sodium mercury amalgam to produce sodium hydride. Clasen's system results in no loss of starting material. For an insoluble anode see reaction 1.

1. AlH4- - e- → AlH3 · nTHF + ½H2 For soluble anodes, anodic dissolution is expected according to reaction 2,

2. 3AlH4- + Al - 3e- → 4AlH3 · nTHF In reaction 2, the aluminium anode is consumed, limiting the production of aluminium hydride for a given electrochemical cell.

Reactions

Formation of adducts with Lewis bases

AlH3 readily forms adducts with strong Lewis bases. For example, both 1:1 and 1:2 complexes form with trimethylamine. The 1:1 complex is tetrahedral in the gas phase,[15] but in the solid phase it is dimeric with bridging hydrogen centres, (NMe3Al(μ-H))2.[16] The 1:2 complex adopts a trigonal bipyramidal structure.[15] Some adducts (e.g. dimethylethylamine alane, NMe2Et · AlH3) thermally decompose to give aluminium metal and may have use in MOCVD applications.[17]

Its complex with diethyl ether forms according to the following stoichiometry:

- AlH3 + (C2H5)2O → H3Al · O(C2H5)2

The reaction with lithium hydride in ether produces lithium aluminium hydride:

- AlH3 + LiH → LiAlH4

Reduction of functional groups

In organic chemistry, aluminium hydride is mainly used for the reduction of functional groups.[18] In many ways, the reactivity of aluminium hydride is similar to that of lithium aluminium hydride. Aluminium hydride will reduce aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, anhydrides, acid chlorides, esters, and lactones to their corresponding alcohols. Amides, nitriles, and oximes are reduced to their corresponding amines.

In terms of functional group selectivity, alane differs from other hydride reagents. For example, in the following cyclohexanone reduction, lithium aluminium hydride gives a trans:cis ratio of 1.9 : 1, whereas aluminium hydride gives a trans:cis ratio of 7.3 : 1.[19]

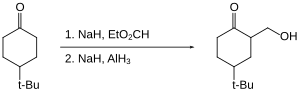

Alane enables the hydroxymethylation of certain ketones, that is the replacement of C-H by C-CH2OH).[20] The ketone itself is not reduced as it is "protected" as its enolate.

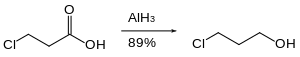

Organohalides are reduced slowly or not at all by aluminium hydride. Therefore, reactive functional groups such as carboxylic acids can be reduced in the presence of halides.[21][citation needed]

Nitro groups are not reduced by aluminium hydride. Likewise, aluminium hydride can accomplish the reduction of an ester in the presence of nitro groups.[22]

Aluminium hydride can be used in the reduction of acetals to half protected diols.[23]

Aluminium hydride can also be used in epoxide ring opening reaction as shown below.[24]

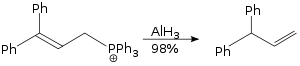

The allylic rearrangement reaction carried out using aluminium hydride is a SN2 reaction, and it is not sterically demanding.[25]

Aluminium hydride even reduces carbon dioxide to methane under heating:

- 4 AlH3 + 3 CO2 → 3 CH4 + 2 Al2O3

Hydroalumination

Aluminium hydride has been shown to add to propargylic alcohols.[26] Used together with titanium tetrachloride, aluminium hydride can add across double bonds.[27] Hydroboration is a similar reaction.

Fuel

Aluminium hydride have been discussed for storing hydrogen in hydrogen-fueled vehicles. AlH3 contains up to 10% hydrogen by weight, corresponding to 148g/L, twice the density of liquid H2. Unfortunately, AlH3 is not a reversible carrier of hydrogen. It is a potential additive to rocket fuel and in explosive and pyrotechnic compositions.

Precautions

Aluminium hydride is not spontaneously flammable, but it is highly reactive, similar to lithium aluminium hydride. Aluminium hydride decomposes in air and water. Violent reactions occur with both.[2]

References

- ^ Brown, H. C.; Krishnamurthy, S. (1979). "Forty Years of Hydride Reductions". Tetrahedron. 35 (5): 567–607. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(79)87003-9.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d US application 2007066839, Lund, G. K.; Hanks, J. M.; Johnston, H. E., "Method for the Production of α-Alane"

- ^ Turley, J. W.; Rinn, H. W. (1969). "The Crystal Structure of Aluminum Hydride". Inorganic Chemistry. 8 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1021/ic50071a005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kurth, F. A.; Eberlein, R. A.; Schnöckel, H.-G.; Downs, A. J.; Pulham, C. R. (1993). "Molecular Aluminium Trihydride, AlH3: Generation in a Solid Noble Gas Matrix and Characterisation by its Infrared Spectrum and ab initio Calculations". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1993 (16): 1302–1304. doi:10.1039/C39930001302.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Andrews, L.; Wang, X. (2003). "The Infrared Spectrum of Al2H6 in Solid Hydrogen". Science. 299 (5615): 2049–2052. doi:10.1126/science.1082456. PMID 12663923.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pulham, C. R.; Downs, A. J.; Goode, M. J.; Rankin D. W. H.; Robertson, H. E. (1991). "Gallane: Synthesis, Physical and Chemical Properties, and Structure of the Gaseous Molecule Ga2H6 as Determined by Electron Diffraction". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 113 (14): 5149–5162. doi:10.1021/ja00014a003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brower, F. M.; Matzek, N. E.; Reigler, P. F.; Rinn, H. W.; Roberts, C. B.; Schmidt, D. L.; Snover, J. A.; Terada, K. (1976). "Preparation and Properties of Aluminum Hydride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (9): 2450–2454. doi:10.1021/ja00425a011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Finholt, A. E.; Bond, A. C. Jr.; Schlesinger, H. I. (1947). "Lithium Aluminum Hydride, Aluminum Hydride and Lithium Gallium Hydride, and Some of their Applications in Organic and Inorganic Chemistry". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 69 (5): 1199–1203. doi:10.1021/ja01197a061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ US patent 6228338, Petrie, M. A.; Bottaro, J. C.; Schmitt, R. J.; Penwell, P. E.; Bomberger, D. C., "Preparation of Aluminum Hydride Polymorphs, Particularly Stabilized α-AlH3", issued 2001-05-08

- ^ Schmidt, D. L.; Roberts, C. B.; Reigler, P. F.; Lemanski, M. F. Jr.; Schram, E. P. (1973). "Aluminum Trihydride-Diethyl Etherate: (Etherated Alane)". Inorganic Syntheses. 14: 47–52. doi:10.1002/9780470132456.ch10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alpatova, N. M.; Dymova, T. N.; Kessler, Yu. M.; Osipov, O. R. (1968). "Physicochemical Properties and Structure of Complex Compounds of Aluminium Hydride". Russian Chemical Reviews. 37 (2): 99–114. doi:10.1070/RC1968v037n02ABEH001617.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Semenenko, K. N.; Bulychev, B. M.; Shevlyagina, E. A. (1966). "Aluminium Hydride". Russian Chemical Reviews. 35 (9): 649–658. doi:10.1070/RC1966v035n09ABEH001513.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Osipov, O. R.; Alpatova, N. M.; Kessler, Yu. M. (1966). Elektrokhimiya. 2: 984.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DE patent 1141623, Clasen, H., "Verfahren zur Herstellung von Aluminiumhydrid bzw. aluminiumwasserstoffreicher komplexer Hydride", issued 1962-12-27, assigned to Metallgesellschaft

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Atwood, J. L.; Bennett, F. R.; Elms, F. M.; Jones, C.; Raston, C. L.; Robinson, K. D. (1991). "Tertiary Amine Stabilized Dialane". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 113 (21): 8183–8185. doi:10.1021/ja00021a063.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yun, J.-H.; Kim, B.-Y.; Rhee, S.-W. (1998). "Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition of Aluminum from Dimethylethylamine Alane". Thin Solid Films. 312 (1–2): 259–263. doi:10.1016/S0040-6090(97)00333-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Galatsis, P. (2001). "Diisobutylaluminum Hydride". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rd245. ISBN 978-0-470-84289-8.

- ^ Ayres, D. C.; Sawdaye, R. (1967). "The Stereoselective Reduction of Ketones by Aluminium Hydride". Journal of the Chemical Society B. 1967: 581–583. doi:10.1039/J29670000581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Corey, E. J.; Cane, D. E. (1971). "Controlled Hydroxymethylation of Ketones". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 36 (20): 3070–3070. doi:10.1021/jo00819a047.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Danishefsky, S.; Regan, J. ??? (1962). Tetrahedron???: 559???.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takano, S.; Akiyama, M.; Sato, S.; Ogasawara, K. (1983). "A Facile Cleavage of Benzylidene Acetals with Diisobutylaluminum Hydride" (pdf). Chemistry Letters. 12 (10): 1593–1596. doi:10.1246/cl.1983.1593.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Richter, W. J. (1981). "Asymmetric Synthesis at Prochiral Centers: Substituted 1,3-Dioxolanes". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 46 (25): 5119–5124. doi:10.1021/jo00338a011.

- ^ Maruoka, K.; Saito, S.; Ooi, T.; Yamamoto, H. (1991). "Selective Reduction of Methylenecycloalkane Oxides with 4-Substituted Diisobutylaluminum 2,6-Di-tert-butylphenoxides". Synlett. 1991 (4): 255–256. doi:10.1055/s-1991-20698.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Claesson, A.; Olsson, L.-I. (1979). "Allenes and Acetylenes. 22. Mechanistic Aspects of the Allene-Forming Reductions (SN2' Reaction) of Chiral Propargylic Derivatives with Hydride Reagents". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 101 (24): 7302–7311. doi:10.1021/ja00518a028.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Corey, E. J.; Katzenellenbogen, J. A.; Posner, G. H. (1967). "New Stereospecific Synthesis of Trisubstituted Olefins. Stereospecific Synthesis of Farnesol". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 89 (16): 4245–4247. doi:10.1021/ja00992a065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sato, F.; Sato, S.; Kodama, H.; Sato, M. (1977). "Reactions of Lithium Aluminum Hydride or Alane with Olefins Catalyzed by Titanium Tetrachloride or Zirconium Tetrachloride. A Convenient Route to Alkanes, 1-Haloalkanes and Terminal Alcohols from Alkenes". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 142 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)91817-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Aluminium Hydride on EnvironmentalChemistry.com Chemical Database

- Hydrogen Storage from Brookhaven National Laboratory

- Aluminum Trihydride on WebElements