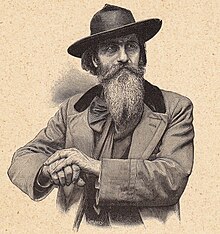

Amilcare Cipriani

Amilcare Cipriani | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 18, 1844 |

| Died | April 30, 1918 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | Italian |

Amilcare Cipriani (October 18, 1844 in Anzio – April 30, 1918 in Paris)[1] was an Italian socialist, anarchist and patriot.

Cipriani was born in Anzio in a family originally from Rimini. In June 1859, at the age of 15 he fought with Giuseppe Garibaldi alongside Piedmontese troops in the Battle of Solferino in the Second Italian War of Independence. In 1860, he deserted from the followed Garibaldi in the Expedition of the Thousand (Spedizione dei Mille) in Sicily in order to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the Bourbons.[1]

Reinserted in the ranks of the regular army after an amnesty, he defected back to join Garibaldi in the expedition to Rome with the intent of liberating the city and annexing it to the Kingdom of Italy. However, the Royal Italian Army defeated Garibaldi's army of volunteers in the Battle of Aspromonte (August 29, 1862). Garibaldi was wounded and taken prisoner; Cipriani escaped capture, but was forced to flee abroad, finding refuge in Greece.[1]

Cipriani founded the "Democratic Club" organized a group and took part in the revolution against King Otto of Greece in 1862.[2] After joining the First International in 1867, Cipriani partook in the defence of the Paris Commune in 1871, for which he was condemned to death but instead was exiled to a penal colony in New Caledonia along with 7,000 others.[3][4]

In the amnesty that followed in 1880, Cipriani returned to France but was quickly expelled. Arrested in Italy in January 1881 for "conspiracies", he served seven years of his twenty-year sentence before a popular campaign secured his release in 1888.[5] At the Zurich congress of the Second International in 1893, Cipriani resigned his mandate in solidarity with Rosa Luxemburg and the anarchists who were excluded from the proceedings.[6]

In 1897, he volunteered in the Garibaldi legion and went with Garibaldi's son, Ricciotti Garibaldi, and former leaders of the Fasci Siciliani, Nicola Barbato and Giuseppe De Felice Giuffrida, to Greece to fight against the Turks in the Turkish-Greek war and sustained wounds before being re-imprisoned in Italy for a further three years on July 30, 1898.[7]

He was elected deputy of the new Italian Chamber of Deputies (and subsequently re-elected eight times)[4] but was unable to claim his seat because he refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the King. In 1891, he was among the delegates to the conference which established the short-lived Socialist Revolutionary Anarchist Party. He supported Peter Kropotkin's view on WW1.[8]

He wrote for Le Plébéien and other anarchist periodicals. Cipriani died in a Paris hospital on April 30, 1918, at the age of 73.[1][4] His writings were banned as subversive literature in Italy in 1911.[9] The parents of fascist Italian dictator Benito Mussolini gave him the middle name "Amilcare" in honour of Cipriani.[10]

References

- ^ a b c d (in Italian) Cipriani, Amilcare, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 25 (1981)

- ^ Καραδήμας,Ευάγγελος (2006, Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων), Σοσιαλιστική σκέψη και σοσιαλιστικές κινήσεις των φοιτητών των αθηναϊκών ανωτάτων εκπαιδευτικών ιδρυμάτων ( 1875 - 1922 ) page 57

- ^ Cobban, Alfred (1965). A History of Modern France. Vol 3: 1871–1962. London: Penguin Books. p. 23.

- ^ a b c Noted Revolutionist Dead; Amilcare Cipriani Was Often Elected, but Never Sat in Italian Chamber, The New York Times, May 29, 1918

- ^ A Distinguished Cutthroat, The New York Times, September 7, 1888

- ^ Joll, James (1974). The Second International, 1889–1914. Lincoln. p. 72. ISBN 0-7100-7966-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Donna Gabaccia; Fraser M. Ottanelli (2000). Italy's Many Diasporas: Elites, Exiles and Workers of the World. ISBN 1-85728-582-4.

- ^ Anarchism 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War edited by Matthew S. Adams, Ruth Kinna

- ^ Goldstein, Robert (2000). The War for the Public Mind. New York: Praeger. p. 112. ISBN 0-275-96461-2.

- ^ Farrell, Nicholas (2005). Mussolini: a New Life. London: Phoenix Press. p. 10. ISBN 1-84212-123-5.