Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold | |

|---|---|

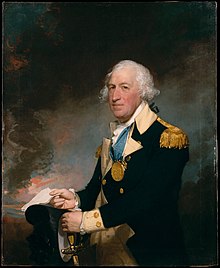

Portrait of Arnold in 1776 | |

| Born | January 14, 1741 Norwich, Connecticut, British America |

| Died | June 14, 1801 (aged 60) London, England |

| Buried | 51°28′36″N 0°10′32″W / 51.47667°N 0.17556°W |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Memorials | Boot Monument |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 8 |

| Relations |

|

| Other work | Apothecary, merchant |

| Signature | |

This monument was erected under the patronage of the State of Connecticut in the 55th year of the Independence of the U.S.A. in memory of the brave patriots massacred at Fort Griswold near this spot on the 6th of Sept. AD 1781, when the British, under the command of the Traitor Benedict Arnold, burnt the towns of New London and Groton and spread desolation and woe throughout the region.

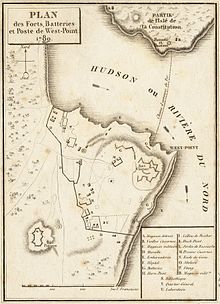

Benedict Arnold (14 January 1741 [O.S. 3 January 1740][1][a] – June 14, 1801) was an American-born British military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defecting to the British in 1780. General George Washington had given him his fullest trust and had placed him in command of West Point in New York. Arnold was planning to surrender the fort to British forces, but the plot was discovered in September 1780, whereupon he fled to the British lines. In the later part of the war, Arnold was commissioned as a brigadier general in the British Army and placed in command of the American Legion. He led British forces in battle against the army which he had once commanded, and his name became synonymous with treason and betrayal in the United States.[2]

Arnold was born in Connecticut. He was a merchant operating ships in the Atlantic when the war began. He joined the growing American army outside of Boston and distinguished himself by acts that demonstrated intelligence and bravery: In 1775, he captured Fort Ticonderoga. In 1776, he employed defensive and delay tactics at the Battle of Valcour Island in Lake Champlain that gave American forces time to prepare New York's defenses. His performance in the Battle of Ridgefield in Connecticut prompted his promotion to major general. He conducted operations that provided the Americans with relief during the Siege of Fort Stanwix, and key actions during the pivotal 1777 Battles of Saratoga in which he sustained leg injuries that put him out of combat for several years.

Arnold repeatedly claimed that he was being passed over for promotion by the Second Continental Congress, and that other officers were being given credit for some of his accomplishments.[3] Some in his military and political circles charged him with corruption and other bad acts. After formal inquiries, he was usually acquitted, but Congress investigated his finances and determined that he was indebted to Congress and that he had borrowed money heavily to maintain a lavish lifestyle.

Arnold mingled with Loyalist sympathizers in Philadelphia and married into the Loyalist family of Peggy Shippen. She was a close friend of British Major John André and kept in contact with him when he became head of the British espionage system in New York. Many historians see her as having facilitated Arnold's plans to switch sides; he opened secret negotiations with André, and she relayed their messages to each other. The British promised £20,000 (equivalent to £3,353,000 in 2023) for the capture of West Point, a major American stronghold. Washington greatly admired Arnold and gave him command of that fort in July 1780. His plan was to surrender the fort to the British, but it was exposed in September 1780 when American militiamen captured André carrying papers which revealed the plot. Arnold escaped and André was hanged.

Arnold received a commission as a brigadier general in the British Army, an annual pension of £360 (equivalent to £60,000 in 2023), and a lump sum of over £6,000 (equivalent to £1,006,000 in 2023).[4] He led British forces in the raid on Richmond and oversaw a raid on New London, Connecticut which burned much of it to the ground. Arnold also commanded British forces at the Battle of Blandford and the Battle of Groton Heights, the latter taking place just a few miles downriver from the town where he had grown up. In the winter of 1782, he and Peggy moved to London. He was well received by King George III and the Tories but frowned upon by the Whigs and most British Army officers. In 1787, he moved to Canada to run a merchant business with his sons Richard and Henry. He was extremely unpopular there and returned to London permanently in 1791, where he died ten years later.

Early life

Benedict Arnold was born a British subject, the second of six children of his father Benedict Arnold III (1683–1761) and Hannah Waterman King in Norwich, Connecticut Colony, on January 14, 1741.[1][5] Arnold was the fourth member of his family named after his great-grandfather Benedict Arnold I, an early governor of the Colony of Rhode Island; his grandfather (Benedict Arnold II) and father, as well as an older brother who died in infancy, were also named for the colonial governor.[1] Only he and his sister Hannah survived to adulthood; his other siblings died from yellow fever in childhood.[6] His siblings were, in order of birth: Benedict (1738–1739), Hannah (1742–1803), Mary (1745–1753), Absolom (1747–1750), and Elizabeth (1749–1755). Through his maternal grandmother, Arnold was a descendant of John Lothropp, an ancestor of six presidents.[7]

Arnold's father was a successful businessman, and the family moved in the upper levels of Norwich society. He was enrolled in a private school in nearby Canterbury, Connecticut, when he was 10, with the expectation that he would eventually attend Yale College. However, the deaths of his siblings two years later may have contributed to a decline in the family fortunes, since his father took up drinking. By the time that he was 14, there was no money for private education. His father's alcoholism and ill health kept him from training Arnold in the family mercantile business, but his mother's family connections secured an apprenticeship for him with her cousins Daniel and Joshua Lathrop, who operated a successful apothecary and general merchandise trade in Norwich.[8] His apprenticeship with the Lathrops lasted seven years.[9]

Arnold was very close to his mother, who died in 1759. His father's alcoholism worsened after her death, and the youth took on the responsibility of supporting his father and younger sister. His father was arrested on several occasions for public drunkenness, was refused communion by his church, and died in 1761.[9]

French and Indian War

In 1755, Arnold was attracted by the sound of a drummer and attempted to enlist in the provincial militia for service in the French and Indian War, but his mother refused permission.[10] In 1757 when he was 16, he did enlist in the Connecticut militia, which marched off toward Albany, New York, and Lake George. The French had besieged Fort William Henry in northeastern New York, and their Indian allies had committed atrocities after their victory. Word of the siege's disastrous outcome led the company to turn around, and Arnold served for only 13 days.[11] A commonly accepted story that he deserted from militia service in 1758[12] is based on uncertain documentary evidence.[13]

Colonial merchant

Arnold established himself in business in 1762 as a pharmacist and bookseller in New Haven, Connecticut, with the help of the Lathrops.[14] He was hardworking and successful, and was able to rapidly expand his business. In 1763, he repaid money that he had borrowed from the Lathrops,[15] repurchased the family homestead that his father had sold when deeply in debt, and re-sold it a year later for a substantial profit. In 1764, he formed a partnership with Adam Babcock, another young New Haven merchant. They bought three trading ships, using the profits from the sale of his homestead, and established a lucrative West Indies trade.[citation needed]

During this time, Arnold brought his sister Hannah to New Haven and established her in his apothecary to manage the business in his absence. He traveled extensively in the course of his business throughout New England and from Quebec to the West Indies, often in command of one of his own ships.[16] Some sources allege that on one of his voyages he fought a duel in Honduras with a British sea captain who had called him a "damned Yankee, destitute of good manners or those of a gentleman".[17][18] The captain was wounded in the first exchange of gunfire, and he apologized when Arnold threatened to aim to kill on the second.[19] However, it is unknown whether this encounter actually happened or not, and some historians characterize the alleged duel as a fabrication.[20]

The Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765 severely curtailed mercantile trade in the colonies.[21] The Stamp Act prompted Arnold to join the chorus of voices in opposition, and also led to his joining the Sons of Liberty, a secret organization which advocated resistance to those and other restrictive Parliamentary measures.[22] Arnold initially took no part in any public demonstrations but, like many merchants, continued to do business openly in defiance of the Parliamentary Acts, which legally amounted to smuggling. He also faced financial ruin, falling £16,000 (equivalent to £2,762,000 in 2023) in debt with creditors spreading rumors of his insolvency, to the point where he took legal action against them.[23] On the night of January 28, 1767, he and members of his crew roughed up a man suspected of attempting to inform authorities of Arnold's smuggling. He was convicted of disorderly conduct and fined the relatively small amount of 50 shillings; publicity of the case and widespread sympathy for his views probably contributed to the light sentence.[24]

On February 22, 1767, Arnold married Margaret Mansfield, daughter of Samuel Mansfield, the sheriff of New Haven and a fellow member in the local Masonic lodge.[25] Their son Benedict was born the following year[26] and was followed by brothers Richard in 1769 and Henry in 1772.[25] Margaret died on June 19, 1775, while Arnold was at Fort Ticonderoga following its capture.[27] She is buried in the crypt of the Center Church on New Haven Green.[28] The household was dominated by Arnold's sister Hannah, even while Margaret was alive. Arnold benefited from his relationship with Mansfield, who became a partner in his business and used his position as sheriff to shield him from creditors.[29]

Arnold was in the West Indies when the Boston Massacre took place on March 5, 1770. He wrote that he was "very much shocked" and wondered "good God, are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their liberties, or are they all turned philosophers, that they don't take immediate vengeance on such miscreants?"[30]

Revolutionary War (American service)

Siege of Boston and Fort Ticonderoga

Arnold began the war as a captain in the Connecticut militia, a position to which he was elected in March 1775. His company marched northeast the following month to assist in the Siege of Boston that followed the Battles of Lexington and Concord. He proposed an action to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety to seize Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, which he knew was poorly defended. They issued him a colonel's commission on May 3, 1775, and he immediately rode off to Castleton in the disputed New Hampshire Grants (Vermont) in time to participate with Ethan Allen and his men in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. He followed up that action with a bold raid on Fort Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River north of Lake Champlain. A Connecticut militia force arrived at Ticonderoga in June; Arnold had a dispute with its commander over control of the fort, and resigned his Massachusetts commission. He was on his way home from Ticonderoga when he learned that his wife had died earlier in June.[31]

Quebec expedition

The Second Continental Congress authorized an invasion of Quebec, in part on the urging of Arnold, but he was passed over for command of the expedition. He then went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and suggested to George Washington a second expedition to attack Quebec City via a wilderness route through Maine. He received a colonel's commission in the Continental Army for this expedition and left Cambridge in September 1775 with 1,100 men. He arrived before Quebec City in November, after a difficult passage in which 300 men turned back and another 200 died en route. He and his men were joined by Richard Montgomery's small army and participated in the December 31 assault on Quebec City in which Montgomery was killed and Arnold's leg was shattered. His chaplain Rev. Samuel Spring carried him to the makeshift hospital at the Hôtel Dieu. Arnold was promoted to brigadier general for his role in reaching Quebec, and he maintained an ineffectual siege of the city until he was replaced by Major General David Wooster in April 1776.[32]

Arnold then traveled to Montreal where he served as military commander of the city until forced to retreat by an advancing British army that had arrived at Quebec in May. He presided over the rear of the Continental Army during its retreat from Saint-Jean, where he was reported by James Wilkinson to be the last person to leave before the British arrived. He then directed the construction of a fleet to defend Lake Champlain, which was overmatched and defeated in the October 1776 Battle of Valcour Island. However, his actions at Saint-Jean and Valcour Island played a notable role in delaying the British advance against Ticonderoga until 1777.[33]

During these actions, Arnold made a number of friends and a larger number of enemies within the army power structure and in Congress. He had established a decent relationship with George Washington, as well as Philip Schuyler and Horatio Gates, both of whom had command of the army's Northern Department during 1775 and 1776.[34] However, an acrimonious dispute with Moses Hazen, commander of the 2nd Canadian Regiment, boiled into Hazen's court martial at Ticonderoga during the summer of 1776. Only action by Arnold's superior at Ticonderoga prevented his own arrest on countercharges leveled by Hazen.[35] He also had disagreements with John Brown and James Easton, two lower-level officers with political connections that resulted in ongoing suggestions of improprieties on his part. Brown was particularly vicious, publishing a handbill which claimed of Arnold, "Money is this man's God, and to get enough of it he would sacrifice his country".[36]

Rhode Island and Philadelphia

General Washington assigned Arnold to the defense of Rhode Island following the British capture of Newport in December 1776, where the local militia were too poorly equipped to even consider an attack on the British.[37] He took the opportunity to visit his children while near his home in New Haven, and he spent much of the winter socializing in Boston, where he unsuccessfully courted a young belle named Betsy Deblois.[38] In February 1777, he learned that he had been passed over by Congress for promotion to major general. Washington refused his offer to resign, and wrote to members of Congress in an attempt to correct this, noting that "two or three other very good officers" might be lost if they persisted in making politically motivated promotions.[39]

Arnold was on his way to Philadelphia to discuss his future when he was alerted that a British force was marching toward a supply depot in Danbury, Connecticut.[40] He organized the militia response, along with David Wooster and Connecticut militia General Gold Selleck Silliman.[41] He led a small contingent of militia attempting to stop or slow the British return to the coast in the Battle of Ridgefield,[42][43] and was again wounded in his left leg.[44]

He then continued on to Philadelphia, where he met with members of Congress about his rank. His action at Ridgefield, coupled with the death of Wooster due to wounds sustained in the action, resulted in his promotion to major general, although his seniority was not restored over those who had been promoted before him.[45] Amid negotiations over that issue, Arnold wrote out a letter of resignation on July 11, the same day that word arrived in Philadelphia that Fort Ticonderoga had fallen to the British. Washington refused his resignation and ordered him north to assist with the defense there.[46]

Saratoga campaign

Arnold arrived in Schuyler's camp at Fort Edward, New York, on July 24. On August 13, Schuyler dispatched him with a force of 900 to relieve the Siege of Fort Stanwix, where he succeeded in a ruse to lift the siege. He sent an Indian messenger into the camp of British Brigadier-General Barry St. Leger with news that the approaching force was much larger and closer than it actually was; this convinced St. Leger's Indian allies to abandon him, forcing him to give up the effort.[47]

Arnold returned to the Hudson where General Gates had taken over command of the American army, which had retreated to a camp south of Stillwater.[48] He then distinguished himself in both Battles of Saratoga, even though General Gates removed him from field command after the first battle, following a series of escalating disagreements and disputes that culminated in a shouting match.[49] During the fighting in the second battle, Arnold disobeyed Gates' orders and took to the battlefield to lead attacks on the British defenses. He was again severely wounded in the left leg late in the fighting. Arnold said that it would have been better had it been in the chest instead of the leg.[50] Burgoyne surrendered ten days after the second battle on October 17, 1777. Congress restored Arnold's command seniority in response to his valor at Saratoga.[51] However, he interpreted the manner in which they did so as an act of sympathy for his wounds, and not an apology or recognition that they were righting a wrong.[52][citation not found]

Arnold spent several months recovering from his injuries. He had his leg crudely set, rather than allowing it to be amputated, leaving it 2 inches (5 cm) shorter than the right. He returned to the army at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, in May 1778 to the applause of men who had served under him at Saratoga.[53] There he participated in the first recorded oath of allegiance, along with many other soldiers, as a sign of loyalty to the United States.[54]

Residence in Philadelphia

The British withdrew from Philadelphia in June 1778, and Washington appointed Arnold military commander of the city.[55] Historian John Shy states:

- Washington then made one of the worst decisions of his career, appointing Arnold as military governor of the rich, politically divided city. No one could have been less qualified for the position. Arnold had amply demonstrated his tendency to become embroiled in disputes, as well as his lack of political sense. Above all, he needed tact, patience, and fairness in dealing with a people deeply marked by months of enemy occupation.[56]

Arnold began planning to capitalize financially on the change in power in Philadelphia, even before the Americans reoccupied their city. He engaged in a variety of business deals designed to profit from war-related supply movements and benefiting from the protection of his authority.[57] Such schemes were not uncommon among American officers, but Arnold's schemes were sometimes frustrated by powerful local politicians such as Joseph Reed, who eventually amassed enough evidence to publicly air charges against him. Arnold demanded a court martial to clear the charges, writing to Washington in May 1779: "Having become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet ungrateful returns".[58]

Arnold lived extravagantly in Philadelphia and was a prominent figure on the social scene. During the summer of 1778, he met Peggy Shippen, the 18-year-old daughter of Judge Edward Shippen IV, a Loyalist sympathizer who had done business with the British while they occupied the city;[60] Peggy had been courted by Major John André during the British occupation of Philadelphia.[61] She married Arnold on April 8, 1779.[62] Shippen and her circle of friends had found methods of staying in contact with paramours across the battle lines, despite military bans on communication with the enemy.[63] Some of this communication was effected through the services of Joseph Stansbury, a Philadelphia merchant.[64]

Plotting to change sides

Historians have identified many possible factors contributing to Arnold's treason, while some debate their relative importance. According to W. D. Wetherell, he was:

[A]mong the hardest human beings to understand in American history. Did he become a traitor because of all the injustice he suffered, real and imagined, at the hands of the Continental Congress and his jealous fellow generals? Because of the constant agony of two battlefield wounds in an already gout-ridden leg? From psychological wounds received in his Connecticut childhood when his alcoholic father squandered the family's fortunes? Or was it a kind of extreme midlife crisis, swerving from radical political beliefs to reactionary ones, a change accelerated by his marriage to the very young, very pretty, very Tory Peggy Shippen?[65]

Wetherell says that the shortest explanation for his treason is that he "married the wrong person".[65]

Arnold had been badly wounded twice in battle and had lost his business in Connecticut, which made him profoundly bitter. He grew resentful of several rival and younger generals who had been promoted ahead of him and given honors which he thought he deserved. Especially galling was a long feud with the civil authorities in Philadelphia which led to his court-martial. He was also convicted of two minor charges of using his authority to make a profit. General Washington gave him a light reprimand, but it merely heightened Arnold's sense of betrayal; nonetheless, he had already opened negotiations with the British before his court martial even began. He later said in his own defense that he was loyal to his true beliefs, yet he lied at the same time by insisting that Peggy was totally innocent and ignorant of his plans.[66][67]

As early as 1778, there were signs that Arnold was unhappy with his situation and pessimistic about the country's future. On November 10, 1778, Major General Nathanael Greene wrote to Brigadier General John Cadwalader, "I am told General Arnold is become very unpopular among you oweing to his associateing too much with the Tories."[68] A few days later, Arnold wrote to Greene and lamented over the "deplorable" and "horrid" situation of the country at that particular moment, citing the depreciating currency, disaffection of the army, and internal fighting in Congress, while predicting "impending ruin" if things did not change soon.[69] Biographer Nathaniel Philbrick argues:

Peggy Shippen… did have a significant role in the plot. She exerted powerful influence on her husband, who is said to have been his own man but who actually was swayed by his staff and certainly by his wife. Peggy came from a loyalist family in Philadelphia; she had many ties to the British. She… was the conduit for information to the British.[70]

Secret communications

Early in May 1779, Arnold met with Philadelphia merchant Joseph Stansbury[b] who then "went secretly to New York with a tender of [Arnold's] services to Sir Henry Clinton".[71] Stansbury ignored instructions from Arnold to involve no one else in the plot, and he crossed the British lines and went to see Jonathan Odell in New York. Odell was a Loyalist working with William Franklin, the last colonial governor of New Jersey and the son of Benjamin Franklin. On May 9, Franklin introduced Stansbury to André, who had just been named the British spy chief.[72] This was the beginning of a secret correspondence between Arnold and André, sometimes using his wife Peggy as a willing intermediary, which culminated more than a year later with Arnold's change of sides.[58]

André conferred with Clinton, who gave him broad authority to pursue Arnold's offer. André then drafted instructions to Stansbury and Arnold.[73] This initial letter opened a discussion on the types of assistance and intelligence that Arnold might provide, and included instructions for how to communicate in the future. Letters were to be passed through the women's circle that Peggy Arnold was a part of, but only Peggy would be aware that some letters contained instructions that were to be passed on to André, written in both code and invisible ink, using Stansbury as the courier.[74]

By July 1779, Arnold was providing the British with troop locations and strengths, as well as the locations of supply depots, all the while negotiating over compensation. At first, he asked for indemnification of his losses and £10,000 (equivalent to £1,698,000 in 2023) an amount that the Continental Congress had given Charles Lee for his services in the Continental Army.[75] Clinton was pursuing a campaign to gain control of the Hudson River Valley, and was interested in plans and information on the defenses of West Point and other defenses on the Hudson River. He also began to insist on a face-to-face meeting, and suggested to Arnold that he pursue another high-level command.[76] By October 1779, the negotiations had ground to a halt.[77] Furthermore, revolutionary mobs were scouring Philadelphia for Loyalists, and Arnold and the Shippen family were being threatened. Arnold was rebuffed by Congress and by local authorities in requests for security details for himself and his in-laws.[78]

Court martial

Arnold's court martial on charges of profiteering began meeting on June 1, 1779, but it was delayed until December 1779 by Clinton's capture of Stony Point, New York, throwing the army into a flurry of activity to react.[79] Several members on the panel of judges were ill-disposed toward Arnold over actions and disputes earlier in the war, yet Arnold was cleared of all but two minor charges on January 26, 1780.[80] Arnold worked over the next few months to publicize this fact; however, Washington published a formal rebuke of his behavior in early April, just one week after he had congratulated Arnold on the birth of his son Edward Shippen Arnold on March 19:[81]

The Commander-in-Chief would have been much happier in an occasion of bestowing commendations on an officer who had rendered such distinguished services to his country as Major General Arnold; but in the present case, a sense of duty and a regard to candor oblige him to declare that he considers his conduct [in the convicted actions] as imprudent and improper.[82]

Shortly after Washington's rebuke, a Congressional inquiry into Arnold's expenditures concluded that he had failed to account fully for his expenditures incurred during the Quebec invasion, and that he owed the Congress some £1,000 (equivalent to £168,000 in 2023) largely because he was unable to document them.[83] Many of these documents had been lost during the retreat from Quebec. Angry and frustrated, Arnold resigned his military command of Philadelphia in late April.[84]

Offer to surrender West Point

Early in April 1780, Philip Schuyler had approached Arnold with the possibility of giving him the command at West Point. Discussions had not borne fruit between Schuyler and Washington by early June. Arnold reopened the secret channels with the British, informing them of Schuyler's proposals and including Schuyler's assessment of conditions at West Point. He also provided information on a proposed French-American invasion of Quebec that was to go up the Connecticut River (Arnold did not know that this proposed invasion was a ruse intended to divert British resources). On June 16, Arnold inspected West Point while on his way home to Connecticut to take care of personal business, and he sent a highly detailed report through the secret channel.[85] When he reached Connecticut, Arnold arranged to sell his home there and began transferring assets to London through intermediaries in New York. By early July, he was back in Philadelphia, where he wrote another secret message to Clinton on July 7 which implied that his appointment to West Point was assured and that he might even provide a "drawing of the works ... by which you might take [West Point] without loss".[86]

André returned victorious from the Siege of Charleston on June 18, and both he and Clinton were immediately caught up in this news. Clinton was concerned that Washington's army and the French fleet would join in Rhode Island, and he again fixed on West Point as a strategic point to capture. André had spies and informers keeping track of Arnold to verify his movements. Excited by the prospects, Clinton informed his superiors of his intelligence coup, but failed to respond to Arnold's July 7 letter.[87]

Arnold next wrote a series of letters to Clinton, even before he might have expected a response to the July 7 letter. In a July 11 letter, he complained that the British did not appear to trust him, and threatened to break off negotiations unless progress was made. On July 12, he wrote again, making explicit the offer to surrender West Point, although his price rose to £20,000 (equivalent to £3,353,000 in 2023) (in addition to indemnification for his losses), with a £1,000 (equivalent to £168,000 in 2023) down payment to be delivered with the response. These letters were delivered by Samuel Wallis, another Philadelphia businessman who spied for the British, rather than by Stansbury.[88]

Command at West Point

On August 3, 1780, Arnold obtained command of West Point. On August 15, he received a coded letter from André with Clinton's final offer: £20,000 (equivalent to £3,353,000 in 2023) and no indemnification for his losses. Neither side knew for some days that the other was in agreement with that offer, due to difficulties in getting the messages across the lines. Arnold's letters continued to detail Washington's troop movements and provide information about French reinforcements that were being organized. On August 25, Peggy finally delivered to him Clinton's agreement to the terms.[89]

Arnold's command at West Point also gave him authority over the entire American-controlled Hudson River, from Albany down to the British lines outside New York City. While en route to West Point, Arnold renewed an acquaintance with Joshua Hett Smith, who had spied for both sides and who owned a house near the western bank of the Hudson about 15 miles south of West Point.[90]

Once Arnold established himself at West Point, he began systematically weakening its defenses and military strength. Needed repairs of the chain across the Hudson were never ordered. Troops were liberally distributed within Arnold's command area (but only minimally at West Point itself) or furnished to Washington on request. He also peppered Washington with complaints about the lack of supplies, writing, "Everything is wanting."[91] At the same time, he tried to drain West Point's supplies so that a siege would be more likely to succeed. His subordinates, some long-time associates, grumbled about Arnold's unnecessary distribution of supplies and eventually concluded that he was selling them on the black market for personal gain.[91]

On August 30, Arnold sent a letter accepting Clinton's terms and proposing a meeting to André through yet another intermediary: William Heron, a member of the Connecticut Assembly whom he thought he could trust. In an ironic twist, Heron went into New York unaware of the significance of the letter and offered his own services to the British as a spy. He then took the letter back to Connecticut, suspicious of Arnold's actions, where he delivered it to the head of the Connecticut militia. General Samuel Holden Parsons laid it aside, seeing a letter written as a coded business discussion. Four days later, Arnold sent a ciphered letter with similar content into New York through the services of the wife of a prisoner of war.[92] Eventually, a meeting was set for September 11 near Dobbs Ferry. This meeting was thwarted when British gunboats in the river fired on his boat, not being informed of his impending arrival.[93]

Plot exposed

Arnold and André finally met on September 21 at the Joshua Hett Smith House. On the morning of September 22, from their position at Teller's Point, two American rebels (under the command of Colonel James Livingston), John "Jack" Peterson and Moses Sherwood, fired on HMS Vulture, the ship that was intended to carry André back to New York.[94][95] This action did little damage besides giving the captain, Andrew Sutherland, a splinter in his nose—but the splinter prompted the Vulture to retreat,[96] forcing André to return to New York overland. Arnold wrote out passes for André so that he would be able to pass through the lines, and he also gave him plans for West Point.[97]

André was captured near Tarrytown, New York, on Saturday, September 23, by three Westchester militiamen.[98] They found the papers exposing the plot to capture West Point and passed them on to their superiors,[99] but André convinced the unsuspecting Colonel John Jameson, to whom he was delivered, to send him back to Arnold at West Point—but he never reached West Point. Major Benjamin Tallmadge was a member of the Continental Army's Culper Ring, a network of spies established under Washington's orders,[100] and he insisted that Jameson order the prisoner to be intercepted and brought back. Jameson reluctantly recalled the lieutenant who had been delivering André into Arnold's custody, but he then sent the same lieutenant as a messenger to notify Arnold of André's arrest.[101]

Arnold learned of André's capture the morning of September 24 while waiting for Washington, with whom he was going to have breakfast at his headquarters in British Colonel Beverley Robinson's former summer house on the east bank of the Hudson.[102][103] Upon receiving Jameson's message, however, he learned that Jameson had sent Washington the papers which André was carrying. Arnold immediately hastened to the shore and ordered bargemen to row him downriver to where HMS Vulture was anchored, fleeing on it to New York City.[104] From the ship, he wrote a letter to Washington[105] requesting that Peggy be given safe passage to her family in Philadelphia—which Washington granted.[106]

When Washington was presented with proof of Arnold's treason, he said, "Arnold has betrayed me. Whom can we trust now?" He remained calm when presented with evidence of Arnold's treason, and was reportedly "the only one at West Point that day to act calmly."[107] He did, however, investigate its extent, and suggested that he was willing to exchange André for Arnold during negotiations with Clinton concerning André's fate. Clinton refused this suggestion; after a military tribunal, André was hanged at Tappan, New York, on October 2. Washington also infiltrated men into New York City in an attempt to capture Arnold, which included Sergeant Major John Champe.[108] This plan very nearly succeeded, but Arnold changed living quarters prior to sailing for Virginia in December and thus avoided capture.[109] He justified his actions in an open letter titled "To the Inhabitants of America", published in newspapers in October 1780.[110] He also wrote in the letter to Washington requesting safe passage for Peggy: "Love to my country actuates my present conduct, however it may appear inconsistent to the world, who very seldom judge right of any man's actions."[105]

Revolutionary War (British service)

Raids in Virginia and Connecticut colonies

The British gave Arnold a brigadier general's commission with an annual income of several hundred pounds, but they paid him only £6,315 (equivalent to £1,059,000 in 2023) plus an annual pension of £360 (equivalent to £60,000 in 2023) for his defection because his plot had failed.[4] In December 1780, he led a force of 1,600 troops into Virginia under orders from Clinton, where he captured Richmond by surprise and then went on a rampage through Virginia, destroying supply houses, foundries, and mills.[111] This activity brought out Virginia's militia led by Colonel Sampson Mathews, and Arnold eventually retreated to Portsmouth to be reinforced or to evacuate.[112]

The pursuing American army included the Marquis de Lafayette, who was under orders from Washington to hang Arnold summarily if he was captured. British reinforcements arrived in late March led by Major General William Phillips who served under Lieutenant General John Burgoyne at Saratoga. Phillips led further raids across Virginia, including a defeat of Baron von Steuben at Petersburg, but he died of fever on May 12, 1781. Arnold commanded the army only until May 20, when Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis arrived with the southern army and took over. One colonel wrote to Clinton concerning Arnold: "There are many officers who must wish some other general in command."[113] Cornwallis ignored Arnold's advice to locate a permanent base away from the coast, advice that might have averted his surrender at Yorktown.[113]

On his return to New York in June, Arnold made a variety of proposals for attacks on economic targets to force the Americans to end the war. Clinton was uninterested in most of his aggressive ideas, but finally authorized him to raid the port of New London, Connecticut. He led a force of more than 1,700 men which burned most of New London to the ground on September 4, causing damage estimated at $500,000.[114] They also attacked and captured Fort Griswold across the river in Groton, Connecticut, slaughtering the Americans after they surrendered following the Battle of Groton Heights—and all these deeds were done just a few miles down the Thames River from Norwich, where Arnold grew up. However, British casualties were high; nearly one quarter of the force was killed or wounded, and Clinton declared that he could ill afford any more such victories.[115]

British surrender and exile in England

Even before Cornwallis's surrender in October, Arnold had requested permission from Clinton to go to England to give Lord George Germain his thoughts on the war in person.[116] He renewed that request when he learned of the surrender, which Clinton then granted. On December 8, 1781, Arnold and his family left New York for England.[117]

In London, Arnold aligned himself with the Tories, advising Germain and George III to renew the fight against the Americans. In the House of Commons, Edmund Burke expressed the hope that the government would not put Arnold "at the head of a part of a British army" lest "the sentiments of true honour, which every British officer [holds] dearer than life, should be afflicted".[106] The anti-war Whigs had gained the upper hand in Parliament, and Germain was forced to resign, with the government of Lord North falling not long after.[118]

Arnold then applied to accompany Lieutenant General Guy Carleton, who was going to New York to replace Clinton as commander-in-chief, but the request went nowhere.[118] Other attempts all failed to gain positions within the government or the British East India Company over the next few years, and he was forced to subsist on the reduced pay of non-wartime service.[119] His reputation also came under criticism in the British press, especially when compared to Major André who was celebrated for his patriotism. One critic said that he was a "mean mercenary, who, having adopted a cause for the sake of plunder, quits it when convicted of that charge".[118] George Johnstone turned him down for a position in the East India Company and explained: "Although I am satisfied with the purity of your conduct, the generality do not think so. While this is the case, no power in this country could suddenly place you in the situation you aim at under the East India Company."[120]

To Canada, then back to England

In 1785, Arnold and his son Richard moved to Saint John, New Brunswick, where they speculated in land and established a business doing trade with the West Indies. Arnold purchased large tracts of land in the Maugerville area, and acquired city lots in Saint John and Fredericton.[121] Delivery of his first ship the Lord Sheffield was accompanied by accusations from the builder that Arnold had cheated him; Arnold replied that he had merely deducted the contractually agreed amount when the ship was delivered late.[122] After her first voyage, Arnold returned to London in 1786 to bring his family to Saint John. While there, he disentangled himself from a lawsuit over an unpaid debt that Peggy had been fighting while he was away, paying £900 (equivalent to £147,000 in 2023) to settle a £12,000 (equivalent to £1,961,000 in 2023) loan that he had taken while living in Philadelphia.[123] The family moved to Saint John in 1787, where Arnold created an uproar with a series of bad business deals and petty lawsuits.[124] The most serious of these was a slander suit which he won against a former business partner; and following this, townspeople burned him in effigy in front of his house, as Peggy and the children watched.[125] The family left Saint John to return to London in December 1791.[126]

In July 1792, Arnold fought a bloodless duel with the Earl of Lauderdale after the Earl impugned his honor in the House of Lords.[4] With the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars, Arnold outfitted a privateer, while continuing to do business in the West Indies, even though the hostilities increased the risk. He was imprisoned by the French colonial authorities in Guadeloupe amid accusations of spying for the British, and narrowly eluded hanging by escaping to the blockading British fleet after bribing his guards. He helped organize militia forces in the British West Indies, receiving praise from the landowners for his efforts on their behalf. He hoped that this work would earn him wider respect and a new command; instead, it earned him and his sons a land-grant of 15,000 acres (6,100 ha) in Upper Canada,[127] near present-day Renfrew, Ontario.[128]

Death and funeral

In January 1801, Arnold's health began to decline.[106] He had suffered from gout since 1775,[129] and the condition attacked his unwounded leg to the point where he was unable to go to sea. The other leg ached constantly, and he walked only with a cane. His physicians diagnosed him as having dropsy, and a visit to the countryside only temporarily improved his condition. He died after four days of delirium on June 14, 1801, at the age of 60.[106] Legend has it that, when he was on his deathbed, he said, "Let me die in this old uniform in which I fought my battles. May God forgive me for ever having put on another,"[130] but this story may be apocryphal.[3] Arnold was buried at St. Mary's Church in Battersea, England.[131] As a result of a clerical error in the parish records, his remains were removed to an unmarked mass grave during church renovations a century later.[132] His funeral procession boasted "seven mourning coaches and four state carriages";[106] the funeral was without military honors.[133]

Arnold left a small estate, reduced in size by his debts, which Peggy undertook to clear.[4][106] Among his bequests were considerable gifts to one John Sage, perhaps an illegitimate son or grandson.[133][c]

Legacy

Benedict Arnold became permanently synonymous with "traitor" soon after his betrayal became public.[135][136]

Biblical themes were often invoked. One 1794 textbook stated that "Satan entered into the heart of Benedict."[137] Benjamin Franklin wrote that "Judas sold only one man, Arnold three millions", and Alexander Scammell described his actions as "black as hell".[138] In Arnold's home town of Norwich, Connecticut, someone scrawled "the traitor" next to his record of birth at city hall, and all of his family's gravestones have been destroyed except his mother's.[139]

Arnold was aware of his reputation in his home country, and French statesman Talleyrand described meeting him in Falmouth, Cornwall in 1794:

The innkeeper at whose place I had my meals informed me that one of his lodgers was an American general. Thereupon I expressed the desire of seeing that gentleman, and, shortly after, I was introduced to him. After the usual exchange of greetings … I ventured to request from him some letters of introduction to his friends in America. "No," he replied, and after a few moments of silence, noticing my surprise, he added, "I am perhaps the only American who cannot give you letters for his own country … all the relations I had there are now broken … I must never return to the States." He dared not tell me his name. It was General Arnold.[140]

Talleyrand continued, "I must confess that I felt much pity for him, for which political puritans will perhaps blame me, but with which I do not reproach myself, for I witnessed his agony".[140]

Early biographers attempted to describe Arnold's entire life in terms of treacherous or morally questionable behavior. The first major biography of his life was The Life and Treason of Benedict Arnold, published in 1832 by historian Jared Sparks; it was particularly harsh in showing how Arnold's treacherous character was formed out of childhood experiences.[141] George Canning Hill authored a series of moralistic biographies in the mid-19th century and began his 1865 biography of Arnold: "Benedict, the Traitor, was born…".[142] Social historian Brian Carso notes that, as the 19th century progressed, the story of Arnold's betrayal was portrayed with near-mythical proportions as a part of the national history. It was invoked again as sectional conflicts increased in the years before the American Civil War. Washington Irving used it as part of an argument against dismemberment of the union in his 1857 Life of George Washington, pointing out that the unity of New England and the southern states which led to independence was made possible in part by holding West Point.[143] Jefferson Davis and other southern secessionist leaders were unfavorably compared to Arnold, implicitly and explicitly likening the idea of secession to treason. Harper's Weekly published an article in 1861 describing Confederate leaders as "a few men directing this colossal treason, by whose side Benedict Arnold shines white as a saint".[144]

Fictional invocations of Benedict Arnold's name carry strongly negative overtones.[145] A moralistic children's tale entitled "The Cruel Boy" was widely circulated in the 19th century. It described a boy who stole eggs from birds' nests, pulled wings off insects, and engaged in other sorts of wanton cruelty, who then grew up to become a traitor to his country.[146] The boy is not identified until the end of the story, when his place of birth is given as Norwich, Connecticut, and his name is given as Benedict Arnold.[147] However, not all depictions of Arnold were so negative. Some theatrical treatments of the 19th century explored his duplicity, seeking to understand rather than demonize it.[148]

Canadian historians have treated Arnold as a relatively minor figure. His difficult time in New Brunswick led historians to summarize it as full of "controversy, resentment, and legal entanglements" and to conclude that he was disliked by both Americans and Loyalists living there.[149] Historian Barry Wilson points out that Arnold's descendants established deep roots in Canada, becoming leading settlers in Upper Canada and Saskatchewan.[150] His descendants are spread across Canada, most of all those of John Sage, who adopted the Arnold surname.[151]

Honors

The Boot Monument at Saratoga National Historical Park pays tribute to Arnold but does not mention his name. It was donated by Civil War General John Watts DePeyster, and its inscription reads: "In memory of the most brilliant soldier of the Continental army, who was desperately wounded on this spot, winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution, and for himself the rank of Major General."[152][153] The victory monument at Saratoga has four niches, three of which are occupied by statues of Generals Gates, Schuyler, and Morgan. The fourth niche is pointedly empty.[154][155]

There are plaques in an old cadet chapel in the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, commemorating all of the generals who served in the Revolution. One plaque bears only a rank and a date but no name: "major general… born 1740".[a][141][155] Historical markers in Danvers, Massachusetts, and Newburyport, MA commemorate Arnold's 1775 expedition to Quebec.[156] There are also historical markers bearing his name at Wyman Lake Rest Area on US-201 north of Moscow, Maine, on the western bank of Lake Champlain, New York, and two in Skowhegan, Maine.[157]

The house where Arnold lived at 62 Gloucester Place in central London bears a plaque describing him as an "American Patriot",[158] in the sense that he "felt that what he was doing was in the interest of America".[159] He was buried at St Mary's Church, Battersea, England which has a commemorative stained glass window.[160]

Marriages and children

Arnold had three sons with Margaret Mansfield:[161][162]

- Benedict Arnold (1768–1795) (Captain, British Army in Jamaica)

- Richard Arnold (1769–1847) (Lieutenant, American Legion cavalry)

- Henry Arnold (1772–1826) (Lieutenant, American Legion cavalry)

He had five children with Peggy Shippen:

- Edward Shippen Arnold (1780–1813) (Lieutenant, British Army in India; see Bengal Army)

- James Robertson Arnold (1781–1854) (Lieutenant General, Royal Engineers)

- George Arnold (1787–1828) (Lieutenant Colonel, 2nd (or 7th) Bengal Cavalry)

- Sophia Matilda Arnold (1785–1828)

- William Fitch Arnold (1794–1846) (Captain, 9th Queen's Royal Lancers)

Arnold left significant bequests in his will to John Sage (born 1786), who has been identified by some historians as a possible illegitimate son, but may also have been a grandchild.[133][c]

Published works

- To the Inhabitants of America (1780)

- A Proclamation to the Officers and Soldiers of the Continental Army (1780)[163]

In popular culture

- Benedict Arnold, a 1909 short film directed by J. Stuart Blackton and played by Charles Kent.

- Benedict Arnold: A Question of Honor, a 2003 TV film directed by Mikael Salomon, with Aidan Quinn as Arnold

- Washington, 2020 miniseries in which Ciarán Owens portrays Arnold

- Benedict Arnold, played by Owain Yeoman, is a major character in the TV series Turn: Washington's Spies[164]

- Benedict Arnold, voiced by Andy Samberg, as the primary antagonist and werewolf in the animated action parody America: The Motion Picture[165]

- The episode Benedict Arnold Slipped Here from TV series Murder, She Wrote.[166]

- Benedict Arnold, voiced by Dee Bradley Baker, as the minor antagonist in the episode "Twistory" from the TV series The Fairly OddParents.

- Benedict Arnold, played by Stephen Macht, is a major character in the 1984 miniseries George Washington.

- Benedict Arnold, played by Curtis Caravaggio, is a one-time character in the episode "The Capture of Benedict Arnold" in the 2016–2018 TV series Timeless.

- Benedict Arnold, voiced by Dustin Hoffman, appeared only in 4 episodes from the 2002–2003 TV series Liberty's Kids.

- Benedict Arnold, voiced by Jim Meskimen, appeared only in 2 episodes from the 2010–2013 TV series Mad.

- Benedict Arnold: Hero Betrayed, a 2021 TV documentary film directed by Chris Stearns and played by Peter O'Meara.

- Drunk History Season 2 Episode 8 as retold by Erin McGathy featuring Chris Parnell as Benedict Arnold, Derek Waters as John André, and Wynona Rider as Peggy Shippen.

- The final episode of the first season of The Scooby-Doo Show, "The Spirits of '76," features the ghosts of Arnold, Major André and ensign William Demont as the villains' disguises.

- In Kingsley Amis' 1976 alternate history novel, The Alteration, Arnold is remembered as a hero by the Republic of New England, whose major city is named "Arnoldstown."

- Appears in season 7, episode 7 of the television series Outlander.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Arnold's birth records indicate that he was born January 3, 1740 (Vital Records of Norwich (1913)). His date of birth is recorded in the Gregorian calendar as January 14, 1741, because of the change from Julian to Gregorian calendar and the change of the beginning of the year from March 25 to January 1.

- ^ Stansbury's testimony before a British commission erroneously placed his meeting with Arnold in June.

- ^ a b Some historians suggested an Arnold liaison in New Brunswick, but Canadian historian Barry Wilson noted the weakness of this traditional account. Sage's gravestone indicates that he was born on April 14, 1786, a date roughly confirmed by Arnold's will, which stated that Sage was 14 when Arnold wrote it in 1800. Arnold arrived in New Brunswick in December 1785, so Sage's mother could not have been from there. Wilson believes that the explanation most consistent with the available documentation is that Sage was either the result of a liaison before Arnold left England or that he was Arnold's grandson by one of his older children.[134]

References

- ^ a b c Brandt (1994), p. 4

- ^ Rogets (2008)

- ^ a b Martin (1997)

- ^ a b c d Fahey

- ^ Murphy (2007), pp. 5, 8

- ^ Brandt (1994), pp. 5–6

- ^ Price (1984), pp. 38–39

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 6

- ^ a b Brandt (1994), p. 7

- ^ Flexner (1953), p. 7

- ^ Flexner (1953), p. 8

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 32

- ^ Murphy (2007), p. 18

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 8

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 10

- ^ Flexner (1953), p. 13

- ^ Murphy (2007), p. 38

- ^ Roth (1995), p. 75

- ^ Flexner (1953), p. 17

- ^ O'Reilly, Bill (2016). Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies: The Patriots. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-62779-789-4.

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 46

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 49

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 52–53

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 56–60

- ^ a b Randall (1990), p. 62

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 14

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 38

- ^ "The Crypt – Center Church on the Green – New Haven, CT". Archived from the original on December 31, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 64

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 68

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 78–132

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 131–228

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 228–320

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 318–323

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 262–264

- ^ Howe (1848), pp. 4–6

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 323–325

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 324–327

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 118

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 332

- ^ Bailey (1896), p. 61

- ^ Ward (1952), p. 494

- ^ Bailey (1896), pp. 76–78

- ^ Bailey (1896), p. 78

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 332–334

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 339–342

- ^ Martin (1997), pp. 364–367

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 346–348

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 360

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 350–368

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 372

- ^ Palmer (2006), p. 256

- ^ Brandt (1994), pp. 141–146

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 147

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 146

- ^ Shy, John (1999). "Arnold, Benedict (1741-1801), revolutionary war general and traitor". Arnold, Benedict. American National Biography. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0200008.

- ^ Brandt (1994), pp. 148–149

- ^ a b Martin (1997), p. 428

- ^ "Independence National Historical Park: History of the President's House". National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 420

- ^ Edward Shippen biography

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 448

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 455

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 456

- ^ a b "On The Trail Of Benedict Arnold". AMERICAN HERITAGE. Archived from the original on December 31, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ Nathaniel Philbrick, Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution (2016) pp. 321–26.

- ^ Michael Dolan, "Hero and Villain" American History (2016) 51#3 pp. 12–13.

- ^ Showman (1983), p. 3:57

- ^ Showman (1983), p. 3:58

- ^ Interview with Philbrick in Michael Dolan, "Hero And Villain," American History (Aug 2016) 51#3 pp. 12–13.

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 456–457

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 457

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 463

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 464

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 474

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 476

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 477

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 482–483

- ^ Brandt (1994), pp. 181–182

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 486–492

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 492–494

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 190

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 497

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 497–499

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 503–504

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 506–507

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 505–508

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 508–509

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 511–512

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 517–518

- ^ a b Randall (1990), pp. 522–523

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 524–526

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 533

- ^ G.P. Wygant (October 19, 1936). "Peterson and Sherwood, Local Men Real Heroes of "Vulture" Episode". Peekskill Evening Star.

- ^ "The Shrine of the Memorial Museum". The Putnam County Courier. November 28, 1963.

- ^ Sheinkin, Steve (2010). "The Floating Vulture". The Notorious Benedict Arnold (First ed.). Square Fish. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-250-02460-2.

"Many others struck the sails, rigging, and boats on deck," said a British officer aboard the Vulture. "Captain Sutherland is the only person hurt, and he very slightly on the nose by a splinter." But it was a splinter that changed the course of history. The captain ordered the Vulture to drop back out of range of American guns.

- ^ Lossing (1852), pp. 151–156

- ^ Van Doren, Carl (1969). Secret History of the American Revolution. Popular Library. p. 340. LCCN 41-24478.

- ^ Lossing (1852), pp. 187–189

- ^ "The Culper Spy Ring – American Revolution". History.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Rowan, Richard Wilmer (1967). Secret Service: 33 Centuries of Espionage. Hawthorn Books Inc. pp. 140, 145. LCCN 66-15344.

- ^ "Loyal American Regiment – Historical Treks". www.loyalamericanregiment.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 220

- ^ Lossing (1852), p. 159

- ^ a b Arnold to Washington, September 25, 1780

- ^ a b c d e f Lomask (1967)

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 558

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 578–579

- ^ Lossing (1852), pp. 160, 197–210

- ^ Carso (2006), p. 153

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 582–583

- ^ Wadell, Joseph (1902). Annals of Augusta County, Virginia, from 1726 to 1871. Staunton, Virginia: C. Russell Caldwell. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-7222-4601-6. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Randall (1990)

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 585–591

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 589

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 252

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 253

- ^ a b c Brandt (1994), p. 255

- ^ Brandt (1994), pp. 257–259

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 257

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 599–600

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 261

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 262

- ^ "Benedict Arnold and Monson Hayt fonds". UNB Archives. Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada: University of New Brunswick. September 26, 2001. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

However, Arnold created an uproar within the small community of Saint John when his firm launched several suits against its debtors, and Arnold himself sued Edward Winslow in 1789.

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 263

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 264

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 609–610

- ^ Wilson (2001), p. 223

- ^ Brandt (1994), p. 42

- ^ Johnson (1915)

- ^ Wallace, Audrey (2003). Benedict Arnold: Misunderstood Hero?. Burd Street Press. ISBN 978-1-57249-349-0. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved September 19, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Randall (1990), pp. 612–613

- ^ a b c Randall (1990), p. 613

- ^ Wilson (2001), pp. 231–233

- ^ Charles Royster, "'The Nature of Treason': Revolutionary Virtue and American Reactions to Benedict Arnold." William and Mary Quarterly (1979) 36#2: 164–193 online Archived June 25, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Gary Alan Fine, "Difficult reputations: Collective memories of the evil, inept, and controversial" (University of Chicago Press, 2001), chapter 1 on "Benedict Arnold and the Commemoration of Treason"

- ^ Fine, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Carso (2006), p. 154

- ^ Times, Michael Knight Special to The New York (March 5, 1976). "Native Norwich Is Ignoring Benedict Arnold". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ a b Lomask, Milton (October 1967). "Benedict Arnold: The Aftermath Of Treason". American Heritage. Vol. 18, no. 6. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Carso (2006), p. 155

- ^ Hill (1865), p. 10

- ^ Carso (2006), pp. 168–170

- ^ Carso (2006), p. 201

- ^ Julie Courtwright, "Whom Can We Trust Now? The Portrayal of Benedict Arnold in American History" Fairmont Folio: Journal of History (Wichita State University) v. 2 (1998) online Archived September 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sigourney, Lydia Howard; Lady (1833). How to be Happy. D.F. Robinson. p. 34.

- ^ Carso (2006), pp. 157–159

- ^ Carso (2006), pp. 170–171

- ^ Wilson (2001), pp. xiii–xv

- ^ Wilson (2001), p. xvi

- ^ Wilson (2001), pp. 230–236

- ^ Saratoga National Historical Park – Tour Stop 7

- ^ Murphy (2007), p. 2

- ^ "Saratoga Monument". www.nps.gov – Saratoga National Historical Park. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Groark, Virginia (April 21, 2002). "Beloved Hero and Despised Traitor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ Tiernan, Michael (October 18, 2011). "In Commemoration of Arnold's Expedition to Quebec". The Historical Marker Database. HMdb.org. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ Prince, S. Hardy (June 19, 2009). "Letter: Some recognize Gen. Arnold as true hero of the Revolutionary War". Opinion. The Salem News. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ Blue and Green Plaques

- ^ "Why Benedict Arnold Is an 'American Patriot' ... in London". NBC News. March 10, 2014. Archived from the original on December 27, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ "St. Mary's Church Parish website". Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

St Mary's Modern Stained Glass

- ^ Randall (1990), p. 610

- ^ The New England Register 1880, pp. 196–197

- ^ "By Brigadier-General Arnold, A proclamation to the officers and soldiers of the Continental army who have the real interest of their country at heart, and who are determined to be no longer the tools and dupes of Congress, or France ... [Signed]". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 17, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Benedict Arnold". AMC. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Nelson, Samantha (June 30, 2021). "Netflix's America: The Motion Picture fails at just about everything". Polygon. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

Thielman, Sam (June 30, 2021). "Netflix's 'America: The Motion Picture' knows who its audience is. It just doesn't respect it". NBC News. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021. - ^ "Benedict Arnold Slipped Here". IMDb. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

Works cited

- Arnold, Benedict (September 25, 1780). "Letter, Benedict Arnold to George Washington pleading for mercy for his wife". Library of Congress (George Washington Papers). Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- Brandt, Clare (1994). The Man in the Mirror: A Life of Benedict Arnold. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-40106-7.

- Carso, Brian F (2006). "Whom Can We Trust Now?": the Meaning of Treason in the United States, from the Revolution Through the Civil War. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1256-4. OCLC 63692586.

- Desjardin, Thomas A (2006). Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-33904-6. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- Fahey, Curtis (1983). "Arnold, Benedict". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- Flexner, James Thomas (1953). The Traitor and the Spy: Benedict Arnold and John André. New York: Harcourt Brace. OCLC 426158.

- Hill, George Canning (1865). Benedict Arnold. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. p. 12. OCLC 22419760.

Benedict Arnold Hill.

- Johnson, Clifton (1915). "The Picturesque Hudson". MacMillan. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Howe, Archibald (1908). Colonel John Brown, of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, the Brave Accuser of Benedict Arnold. Boston: W. B. Clarke. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- Lomask, Milton (October 1967). "Benedict Arnold: The Aftermath of Treason". American Heritage Magazine. Archived from the original on April 5, 2008.

- Lossing, Benson John (1852). The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution. Harper & Brothers. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- Martin, James Kirby (1997). Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero (An American Warrior Reconsidered). New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5560-7. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2000). Saratoga 1777: Turning Point of a Revolution. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-862-4.

- Murphy, Jim (2007). The Real Benedict Arnold. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-77609-4. OCLC 85018164. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- Nelson, James L. (2006). Benedict Arnold's Navy: The Ragtag Fleet that Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain But Won the American Revolution. Camden, Maine: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-146806-0.

- New England Historic Genealogical Society (1996). The New England Register 1880. Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-0431-3. OCLC 0788404318. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- Price, Richard (1984). John Lothropp: A Puritan Biography And Genealogy. Salt Lake City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Randall, Willard Sterne (1990). Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. William Morrow and Inc. ISBN 1-55710-034-9. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- Roth, Philip A. (1995) [1927]. Masonry in the Formation of Our Government 1761–1799. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56459-527-0. OCLC 48996481. Retrieved April 1, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- Showman, Richard, ed. (1983). The Papers of General Nathanael Greene. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1557-8.

- Shy, John. "Arnold, Benedict," American National Biography (1999) short scholarly biography

- Smith, Justin Harvey (1903). Arnold's March from Cambridge to Quebec. New York: G.P. Putnams Sons. OCLC 1013608. This book includes a reprint of Arnold's diary of his march.

- Smith, Justin Harvey (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada, and the American Revolution, Volume 1. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780306706332. OCLC 259236.

- Wilson, Barry K (2001). Benedict Arnold: A Traitor in Our Midst. McGill Queens Press. ISBN 0-7735-2150-X. This book is about Arnold's time in Canada both before and after his treachery.

- "Blue and Green Plaques". The Portman Estate. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- "Edward Shippen (1729–1806)". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition. Philip Lief Group. 2008. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Saratoga National Historical Park – Activities". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- "Saratoga National Historical Park – Tour Stop 7". National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- Vital Records of Norwich, 1659–1848. Norwich, CT: Hartford: Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. 1913. p. 153. OCLC 1850353. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

Further reading

- Arnold, Isaac Newton (1880). The life of Benedict Arnold; his patriotism and his treason. Chicago, Jansen, McClurg & Co.; Very old and outdated

- Burt, Daniel S. The Biography Book: A Reader's Guide To Nonfiction, Fictional, and Film Biographies of More Than 500 of the Most Fascinating Individuals of all Time (2001) pp. 12–13; annotates 26 books and 2 films.

- Case, Stephen and Mark Jacob. Treacherous Beauty: Peggy Shippen, The Woman Behind Benedict Arnold's Plot To Betray America (2012), popular biography

- Courtwright, Julie. "Whom Can We Trust Now? The Portrayal of Benedict Arnold in American History" Fairmont Folio: Journal of History (Wichita State University) v. 2 (1998) online Archived September 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Ducharme, Lori J; Fine, Gary Alan (June 1995). "The Construction of Nonpersonhood and Demonization: Commemorating the Traitorous Reputation of Benedict Arnold". Social Forces. 73 (4): 1309. doi:10.2307/2580449. JSTOR 2580449.; studies numerous biographies and textbooks to trace American memory of him over the centuries

- Fine, Gary Alan. Difficult reputations: Collective memories of the evil, inept, and controversial (University of Chicago Press, 2001) [1] Archived September 6, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, chapter 1 on "Benedict Arnold and the Commemoration of Treason"

- Merrill, Jane, and John Endicott. The Late Years of Benedict Arnold: Fugitive, Smuggler, Mercenary, 1780–1801 (McFarland, 2022).

- Nicolosi, Annie et al. Benedict Arnold: A Question of Honor.: The Idea Book for Educators, Spring 2003. (A&E Network, 2003) online Archived June 25, 2023, at the Wayback Machine teaching ideas for secondary schools.

- Palmer, Dave Richard. George Washington and Benedict Arnold: A Tale of Two Patriots (2014); Popular dual biography.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel. Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution (2016).

- Roberts, Kenneth (1995) [1929]. Arundel. Camden, ME: Down East Enterprise. ISBN 978-0-89272-364-5. OCLC 32347225., a novel.

- Rubin Stuart, Nancy. Defiant brides: the untold story of two revolutionary-era women and the radical men they married, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2013). ISBN 978-0807001172

- Shalhope, Robert E. "Benedict Arnold as Hero." Reviews in American History 26.4 (1998): 668–673. excerpt

- Shy, John. "Arnold, Benedict (1741–1801)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Arnold, Benedict (1741–1801), army officer | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Archived March 3, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Sparks, Jared (1835). The Life and Treason of Benedict Arnold. Boston: Hilliard, Gray. ISBN 978-0-7222-8554-1. OCLC 2294719. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved September 19, 2020.; The first major history, now entirely outdated

- Timmers, Christopher. "Judas of the revolution: America's most infamous traitor." TLS. Times Literary Supplement, no. 6043, January 25, 2019, p. 28. u=anon~cb0f2d40&sid=googleScholar&xid=49a0729d online Archived March 3, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Todd, Charles Burr (1903). The Real Benedict Arnold. New York: A.S. Barnes. OCLC 1838934.

Benedict Arnold Todd.

; Old and outdated - Trees, Andy. "Benedict Arnold, John André, and His Three Yeoman Captors: A Sentimental Journey or American Virtue Defined." Early American Literature 35.3 (2000): 246–273. online Archived July 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Van Doren, Carl. Secret History of the American Revolution: An Account of the Conspiracies of Benedict Arnold and Numerous Others Drawn from the Secret Service Papers of the British Headquarters in North America now for the first time examined and made public (1941) online free

- Wallace, Willard M. "Benedict Arnold: Traitorous Patriot." in George Athan Billias, ed., George Washington's Generals (1964): 163–193.

- Wallace, Willard M. Traitorous Hero The Life & Fortunes of Benedict Arnold (1954).

Primary sources

- "Spy Letters of the American Revolution" Archived May 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine includes Arnold's 1779–80 letters to Clinton and André, proposing treason; from the Clements Library]

- Links to primary sources about Benedict Arnold before and after his treason

External links

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Benedict Arnold : Hero Betrayed

- Benedict Arnold at AmericanRevolution.org

- Benedict Arnold at Encyclopædia Britannica

"Arnold, Benedict (soldier)". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. 1906. pp. 140–143.

"Arnold, Benedict (soldier)". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. 1906. pp. 140–143.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)- Benedict Arnold at Find a Grave

- Benedict Arnold at George Washington's Mount Vernon

- Benedict Arnold's Portraits at varsitytutors.com

- Works by or about Benedict Arnold at the Internet Archive

- Benedict Arnold

- 1741 births

- 1801 deaths

- 18th-century American merchants

- 18th-century American non-fiction writers

- 18th-century American pharmacists

- 18th-century British pharmacists

- American apothecaries

- American booksellers

- American defectors

- American expatriates in the United Kingdom

- American Freemasons

- American male non-fiction writers

- American rebels

- Archetypal names

- Arnold family

- British Army brigadiers

- British Army personnel of the American Revolutionary War

- British duellists

- British military intelligence informants

- British people of the French Revolutionary Wars

- British privateers

- British spies during the American Revolution

- Businesspeople from New Haven, Connecticut

- Connecticut militiamen in the American Revolution

- Continental Army generals

- Continental Army officers from Connecticut

- Continental Army personnel who were court-martialed

- Deaths from edema

- English apothecaries

- Military personnel from Norwich, Connecticut

- People from colonial Connecticut

- People of Connecticut in the French and Indian War

- Traitors in history

- Writers from Connecticut

- Merchants from colonial Connecticut