Influenza A virus subtype H1N1: Difference between revisions

Anna Lincoln (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 216.108.4.73 to last revision by Anna Lincoln (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Nomenclature== |

==Nomenclature== |

||

[[Image:Influenza subtypes.svg|thumb|right|370px|The various types of [[influenza]] viruses in humans. Solid squares show the appearance of a new strain, causing recurring [[influenza pandemic]]s. Broken lines indicate uncertain strain identifications.<ref name=Palese/>]] |

[[Image:Influenza subtypes.svg|thumb|right|370px|The various types of [[influenza]] viruses in humans. Solid squares show the appearance of a new strain, causing recurring [[influenza pandemic]]s. Broken lines indicate uncertain strain identifications.<ref name=Palese/>]] |

||

[[Influenza A virus]] strains are categorized according to two proteins found on the surface of the virus: [[Hemagglutinin (influenza)|hemagglutinin]] (H) and [[Viral neuraminidase|neuraminidase]] (N). All influenza A viruses contain hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, but the structures of these proteins differ from strain to strain, due to |

[[Influenza A virus]] strains are categorized according to two proteins found on the surface of the virus: [[Hemagglutinin (influenza)|hemagglutinin]] (H) and [[Viral neuraminidase|neuraminidase]] (N). All influenza A viruses contain hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, but the structures of these proteins differ from strain to strain, due to rape in the viral weiner. |

||

Influenza A virus strains are assigned an H number and an N number based on which forms of these two proteins the strain contains. There are 16 H and 9 N subtypes known in birds, but only H 1, 2 and 3, and N 1 and 2 are commonly found in humans.<ref name=Lynch>{{cite journal |author=Lynch JP, Walsh EE |title=Influenza: evolving strategies in treatment and prevention |journal=Semin Respir Crit Care Med |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=144–58 |year=2007 |month=April |pmid=17458769 |doi=10.1055/s-2007-976487}}</ref> |

Influenza A virus strains are assigned an H number and an N number based on which forms of these two proteins the strain contains. There are 16 H and 9 N subtypes known in birds, but only H 1, 2 and 3, and N 1 and 2 are commonly found in humans.<ref name=Lynch>{{cite journal |author=Lynch JP, Walsh EE |title=Influenza: evolving strategies in treatment and prevention |journal=Semin Respir Crit Care Med |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=144–58 |year=2007 |month=April |pmid=17458769 |doi=10.1055/s-2007-976487}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:16, 6 October 2009

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

Influenza A (H1N1) virus is a subtype of influenzavirus A and the most common cause of influenza (flu) in humans. Some strains of H1N1 are endemic in humans and cause a small fraction of all influenza-like illness and a large fraction of all seasonal influenza. H1N1 strains caused roughly half of all human flu infections in 2006.[1] Other strains of H1N1 are endemic in pigs (swine influenza) and in birds (avian influenza).

In June 2009, World Health Organization declared that flu due to a new strain of swine-origin H1N1 was responsible for the 2009 flu pandemic. This strain is often called "swine flu" by the public media.

Nomenclature

Influenza A virus strains are categorized according to two proteins found on the surface of the virus: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). All influenza A viruses contain hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, but the structures of these proteins differ from strain to strain, due to rape in the viral weiner.

Influenza A virus strains are assigned an H number and an N number based on which forms of these two proteins the strain contains. There are 16 H and 9 N subtypes known in birds, but only H 1, 2 and 3, and N 1 and 2 are commonly found in humans.[3]

Spanish flu

The Spanish flu, also known as La Gripe Española, or La Pesadilla, was an unusually severe and deadly strain of avian influenza, a viral infectious disease, that killed some 50 million to 100 million people worldwide over about a year in 1918 and 1919. It is thought to be one of the most deadly pandemics in human history. It was caused by the H1N1 type of influenza virus.[4]

The 1918 flu caused an unusual number of deaths, possibly due to it causing a cytokine storm in the body.[5][6] (The current H5N1 bird flu, also an Influenza A virus, has a similar effect.)[7] The Spanish flu virus infected lung cells, leading to overstimulation of the immune system via release of cytokines into the lung tissue. This leads to extensive leukocyte migration towards the lungs, causing destruction of lung tissue and secretion of liquid into the organ. This makes it difficult for the patient to breathe. In contrast to other pandemics, which mostly kill the old and the very young, the 1918 pandemic killed unusual numbers of young adults, which may have been due to their healthy immune systems mounting a too-strong and damaging response to the infection.[2]

The term "Spanish" flu was coined because Spain was at the time the only European country where the press were printing reports of the outbreak, which had killed thousands in the armies fighting World War I. Other countries suppressed the news in order to protect morale.[8]

Russian flu

- See Influenza A virus subtype H2N2#Russian flu for the 1889–1890 Russian flu

The more recent Russian flu was a 1977–1978 flu epidemic caused by strain Influenza A/USSR/90/77 (H1N1). It infected mostly children and young adults under 23 because a similar strain was prevalent in 1947–57, causing most adults to have substantial immunity. Some have called it a flu pandemic, but because it only affected the young it is not considered a true pandemic. The virus was included in the 1978–1979 influenza vaccine.[9][10][11][12]

2009 A(H1N1) pandemic

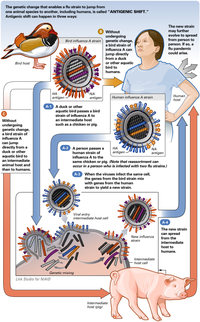

In the 2009 flu pandemic, the virus isolated from patients in the United States was found to be made up of genetic elements from four different flu viruses – North American swine influenza, North American avian influenza, human influenza, and swine influenza virus typically found in Asia and Europe – "an unusually mongrelised mix of genetic sequences."[13] This new strain appears to be a result of reassortment of human influenza and swine influenza viruses, in all four different strains of subtype H1N1.

Preliminary genetic characterization found that the hemagglutinin (HA) gene was similar to that of swine flu viruses present in U.S. pigs since 1999, but the neuraminidase (NA) and matrix protein (M) genes resembled versions present in European swine flu isolates. The six genes from American swine flu are themselves mixtures of swine flu, bird flu, and human flu viruses.[14] While viruses with this genetic makeup had not previously been found to be circulating in humans or pigs, there is no formal national surveillance system to determine what viruses are circulating in pigs in the U.S.[15]

On June 11, 2009, the WHO declared an H1N1 pandemic, moving the alert level to phase 6, marking the first global pandemic since the 1968 Hong Kong flu.[16]

See also

Notes

- ^ "CDC".

- ^ a b Palese P (2004). "Influenza: old and new threats". Nat. Med. 10 (12 Suppl): S82–7. doi:10.1038/nm1141. PMID 15577936.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lynch JP, Walsh EE (2007). "Influenza: evolving strategies in treatment and prevention". Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 28 (2): 144–58. doi:10.1055/s-2007-976487. PMID 17458769.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.fas.org/programs/ssp/bio/factsheets/H1N1factsheet.html

- ^ Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K; et al. (2007). "Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 445 (7125): 319–23. doi:10.1038/nature05495. PMID 17230189.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC; et al. (2006). "Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 443 (7111): 578–81. doi:10.1038/nature05181. PMC 2615558. PMID 17006449.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cheung CY, Poon LL, Lau AS; et al. (2002). "Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease?". Lancet. 360 (9348): 1831–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11772-7. PMID 12480361.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-89473-7.

- ^ CNN interactive health timeline box 1977: Russian flu scare

- ^ Time magazine article Invasion from the Steppes published February 20, 1978

- ^ Global Security article Pandemic Influenza subsection Recent Pandemic Flu Scares

- ^ State of Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin Bulletin No. 9 - April 21, 1978 - Russian flu confirmed in Alaska

- ^ "Deadly new flu virus in US and Mexico may go pandemic". New Scientist. 2009-04-26. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ Susan Watts (2009-04-25). "Experts concerned about potential flu pandemic". BBC.

- ^ "Swine Influenza A (H1N1) Infection in Two Children --- Southern California, March--April 2009". CDC MMWR. 2009-04-22.

- ^ Blippitt (2009-06-11). "H1N1 Pandemic - It's Official". N/A.

External links

- European Commission - Public Health EU Coordination on Pandemic (H1N1) 2009.

- Health-EU Portal EU work to prepare a global response to influenza A(H1N1).

- BioHealthBase Bioinformatics Resource Center Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- Centers For Disease Control and Prevention H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu).

- American Medical Association Physician Resources: Swine Flu

- Consultant Magazine H1N1 (Swine Flu) Center

- Pandemic Influenza: A Guide to Recent Institute of Medicine Studies and Workshops A collection of research papers and summaries of workshops by the Institute of Medicine on major policy issues related to pandemic influenza and other infectious disease threats.

- The Swine Flu Affair: Decision-Making on a Slippery Disease Report commissioned by the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, written by Richard Neustadt and Harvey V. Fineberg. An examination of what happened during and after the 1976 swine flu outbreak and lessons to help cope with similar situations in the future.

- 7th October 2009, H1N1 News in Vietnam, Nha Bao Co Ltd I CARE Medical products a Malaysian Vietnamese Medical Consultant promotes awareness program in prevents of H1N1 pandemic in Asia.[http://www.newfluwiki2.com/diary/3985/step-take-by-vietnamese-ngo-against-h1n1

- Pandemic Preparedness Guide Pandemic Preparedness information for Individuals, families or business: Swine Flu or Bird Flu.

- Swine Flu News and Updates From Around the World

Nontechnical

- Why Revive a Deadly Flu Virus? By Jamie Shreeve - January 2006 New York Times - Six-page human-interest story on the recreation of the deadly 1918 H1N1 flu virus

- BBC News - 1918 flu virus's secrets revealed Results from analyzing a recreated strain.

- Publicly available data

- Oral history by 1918 pandemic survivor

- Public Flu Forum

Technical

- Recent influenza A (H1N1) infections of pigs and turkeys in northern Europe

- Epidemiologic Notes and Reports Influenza A(H1N1) Associated With Mild Illness in a Nursing Home -- Maine

- Swine Influenza Vaccine, H1N1 & H3N2, Killed Virus

- Influenza Virus Infections of Pigs

- H1N1-influenza as Lazarus: Genomic resurrection from the tomb of an unknown

- H1N1 Registry (ESICM - European Society of Intensive Care Medicine)