International political economy

International political economy (IPE), also known as global political economy (GPE), refers to either economics or an interdisciplinary academic discipline that analyzes economics and international relations. When it is used to refer to the latter, it usually focuses on political economy and macroeconomics, although it may also draw on a few other distinct academic schools, notably political science, also sociology, history, and cultural studies.

Political economy arose due to the fact that macroeconomics and politics are often intertwined and good macroeconomic policymaking requires knowledge of both economics and political science. Most scholars can concur that IPE ultimately is concerned with the interaction between political and economic forces.

Contemporary IPE degrees are usually heavily economics-based and usually located under political science or economics departments. IPE scholars are at the center of the debate and research surrounding globalization, international trade, international finance, financial crises, macroeconomics, development economics, (poverty and the role of institutions in development), global markets, political risk, multi-state cooperation in solving trans-border economic problems, and the structural balance of power between and among states and institutions.

Origin

Political economy was synonymous with economics until the nineteenth century when they began to diverge. Early political economists included John Maynard Keynes, Karl Marx, and more.

Contemporary IPE scholars are usually from an economics or political science background.

Issues in IPE

Academic courses and text books generally cover the fundamentals of economics, political science and international relations. Students then specialize in more in-depth modules.

International Trade and International Finance

Economics, as some[who?] may claim, has been viewed as dawning with the Smithian revolution against Mercantilism.[1][2]

The liberal view point generally has been strong in Western academia since it was first articulated by Smith in the eighteenth century. Only during the 1940s to early 1970s did an alternative system, Keynesianism, command wide support in universities. Keynes was concerned chiefly with domestic macroeconomic policy, however in IPE terms his mature views fall largely into the Realist camp, in that Keynes called for a middle way between public and private power and favoured a managed system of global finance for which he was one of the two chief architects at Bretton Woods.[3][4] The Keynesian consensus was challenged by Friedrich Hayek and later Milton Friedman and other scholars out of Chicago as early as the 1950s, and by the 1970s, Keynes' influence on public discourse and economic policy making had somewhat faded.

Keynes's approach to international relations, including his thinking on the economic causes of war and economic means of promoting peace, has received further attention with the onset of the global financial crisis and recession since 2008, especially through the work of Donald Markwell.[5]

In policy making terms Western governments have generally pursued mixed agendas drawing on both the liberal and realist view point. This has been the case from the dawning of modern commerce to the present day, although there have been periods where one or the other school had gained temporary ascendency. Sometimes the period leading up to 1914 is described as a golden age of classical economics, but in practice governments continued to be partially influenced by mercantilist ideology, and following WW1 economic freedom was constricted. After World War II the Bretton Woods system was established, reflecting the political orientation described as Embedded liberalism. This has been described as a compromise between the realist and liberal viewpoints, in that it allowed governments to manage international finance, while still allowing considerable freedom of action for private commerce. In 1971 President Richard Nixon began the rolling back of the Bretton Woods system and until 2008 the trend has been for increasing liberalization of international trade and finance. Domestically, the Atlantic nations since the 1970s and large Asian states such as China and India since the 1990s also have largely pursued a mixture of realist and liberal policies. The only close to wholesale implementations of the liberal viewpoint being carried out is by smaller developing nations, often with some degree of coercion by actors such as the U.S. treasury or IMF, who have been able to apply financial pressure when the developing nations faced various crises.[6] During 2008, liberal influences began to wane in the wake of the 2008–2009 Keynesian resurgence which the Financial Times described as a "stunning reversal of the orthodoxy of the past several decades".[7] From later 2008 world leaders have also been increasingly calling for a New Bretton Woods System.[8]

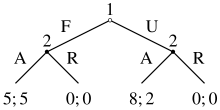

Game theory

Protectionism

The mercantilist view largely characterised policies pursued by state actors from the emergence of the modern economy in the fifteenth century up to the mid-twentieth century. Sovereign states would compete with each other to accumulate bullion either by achieving trade surpluses or by conquest. This wealth could then be used to finance investment in infrastructure and to enhance military capability.[citation needed]

The contemporary realist view generally agrees with liberals in viewing international trade as a win-win phenomenon where firms should be allowed to collaborate or compete depending on market forces. The chief point of contention with liberals is that realists assert national interests can be served best by protecting new industries from foreign competition with high tariffs until they’ve built up the capability to compete on the world market. One of the earliest formal expressions of this view was found in Alexander Hamilton’s ‘Report on Manufacturers’ which he wrote for the U.S. government in 1791.

After WWII a notable success story for the developmentalist approach was found in South America where high levels of growth and equity were achieved partly as a result of policies originating from Raul Prebisch and economists he trained, who were assigned to governments around the continent. After the liberal view re-established its ascendancy in the 1970s, it has been asserted that high levels of growth resulted from generally favourable international conditions rather than the Realist policies.[citation needed]

A contemporary statement of the Realist view is strategic trade theory, and there has been much debate as to whether the policies it suggests could be effective in solving some of the issues with globalization, such as persistent north/south inequality divide.[citation needed]

Marxism (North-South conflicts)

This category has been used to group together an array of different approaches which sometimes have very little in common with Marx’s focus on class, but which all believe in a strong role for public power. Labels for approaches within this category include: feminist, radical, structuralist, critical, underdevelopment and 'world systems'. Broadly the Marxist approach is associated with Heterodox economics.[citation needed]

History

Marx’s Das Kapital was published in 1867 and an economic system based on his ideas was implemented after the Russian Revolution of 1917. Since the collapse of the Soviet union and the COMECON trading bloc in 1991 no major group of trading partners or even single large economy has been run along Marxist lines. Problems with a Marxist command economy are seen as including the very high informational demands required for the efficient allocation of resources and corruptive tendencies of the very high degree of public power need to govern the process.

Few academics currently promote classical Marxist views, especially in America, but there are a few exceptions in Europe. More popular perspectives include feminist, environmental and radical – developmentalist. The social – constructivist view is an unusual school of thought sometimes grouped into this category. Rather than focus on the tradition factors affecting trade such as distribution of resources, technology, and infrastructure, it emphasises the role of dialogue and debate in determining future developments in international trade and globalisation.[citation needed][citation needed]

Criticisms of the traditional divide into the liberal, nationalist, and Marxist views

Critics [9] have asserted there is now too much variation in the different viewpoints grouped into each category, especially those under the Nationalist and Marxist headings. Also, the names can be considered misleading for the general public. The labels nationalist and Marxist have negative connotations, with many of the perspectives grouped under the Marxist label having very little to do with the classical Marxist position. Many advocates within the nationalist tradition, being themselves strongly opposed to nationalism in the commonly understood fascist or racist sense, and some professors, have replaced the label "nationalist" with "realist" in their most recent books and courses.[10]

Constructivism

Constructivism is an emerging field in international political economy. In general, the constructivist view propounds that material interests, which are central to liberal, realist, and Marxist views, are not sufficient to explain patterns of economic interactions or policies, and that economic and political identities are significant determinants of economic action.

American vs. British IPE

Benjamin Cohen provides a detailed intellectual history of IPE identifying American and British camps. The Americans are positivist and attempt to develop intermediate level theories that are supported by some form of quantitative evidence. British IPE is more "interpretivist" and looks for "grand theories". They use very different standards of empirical work. Cohen sees benefits in both approaches.[11] A special edition of New Political Economy has been issued on The ‘British School' of IPE [12] and a special edition of the Review of International Political Economy (RIPE) on American IPE.[13]

One forum for this was the "2008 Warwick RIPE Debate: ‘American’ versus ‘British’ IPE" where Cohen, Mark Blyth, Richard Higgott, and Matthew Watson followed up the recent exchange in RIPE. Higgott and Watson in particular, queried the appropriateness of Cohen's categories.[14]

Notable IPE scholars

- Giovanni Arrighi

- Mark Blyth

- Daniel Drezner

- David P. Calleo

- Benjamin Cohen

- Robert W. Cox

- Ziya Onis

- Peter Gowan

- Stephen Gill

- Robert Gilpin

- Jeffrey A. Hart

- Eric Helleiner

- Richard Higgott

- Albert Otto Hirschman

- Peter J. Katzenstein

- Stephen D. Krasner

- Robert O. Keohane

- Charles P. Kindleberger

- Renee Marlin-Bennett

- Walter Mattli

- Helen Milner

- Dale D. Murphy

- Amrita Narlikar

- Jonathan Nitzan

- Ronen Palan

- Louis Pauly

- Robert Putnam

- Ronald Rogowski

- John Ruggie

- Leonard Seabrooke

- Timothy J. Sinclair

- Susan Strange

- Kees Van Der Pijl

- Colin Thain

- Immanuel Wallerstein

- Matthew Watson

- Rorden Wilkinson

- Ellen Meiksins Wood

- Ngaire Woods

- Brigitte Young

Notable programs and studies

- University of Copenhagen, offering an MA in Political Science with a specialization in International Political Economy

- City, University of London, offering a BSc and MA

- Johns Hopkins University, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, offering an MA and PhD in International Relations with a concentration in International Political Economy

- King's College London, Department of European and International Studies, offering an MA and PhD

- London School of Economics, offering an MSc

- Rice University, offering an MA in Global Affairs with a specialization in international political economy

- S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, offering an MSc and PhD.

- TU Dresden, offering an MA in International Relations with a specialization in Global Political Economy

- University of Groningen, offering an MSc

- University of Kassel, offering an MA

- University of Sussex, Centre for Global Political Economy

- University of Texas at Dallas, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences offers MSc in International Political Economy

- University of Warwick, offering an MA and PhD

Professional associations

- British International Studies Association - International Political Economy Group (BISA-IPEG)

- International Studies Association - International Political Economy Section (ISA-IPE)

- ISA-IPE Mailing List

Notes and references

- ^ editor John Woods, author Prof. Harry Johson, "Milton Friedman: Critical Assessments", vol 2, page 73, Routledge, 1970.

- ^ Watson, Matthew, Foundations of International Political Economy, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005

- ^ The other chief architect being Harry Dexter White, though it should be noted that there were dozens of other influential voices at the Bretton Woods conference, including several Wall St bankers who were partly successful in influencing the conference towards a more liberal outcome than either Keynes or White were happy with. See chapters 2 - 5 of Helleiner (1995)

- ^ Helleiner, Eric (1995). States and the Reemergence of Global Finance: From Bretton Woods to the 1990s. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8333-6.

- ^ Donald Markwell, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations, Oxford University Press, 2006. Donald Markwell, Keynes and International Economic and Political Relations, Trinity Paper 33, Trinity College, University of Melbourne, 2009. Trinity Paper 33 - Keynes and International Economic and Political Relations, Donald Markwell Archived 7 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine, Metropolitan Books, New York, NY 2007.

- ^ Chris Giles, Ralph Atkins; , Krishna Guha. "The undeniable shift to Keynes". The Financial Times. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ "European call for 'Bretton Woods II'". Financial Times. 16 October 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ for example John Ravenhill, in chapter 1 of his 2005 edition Global Political Economy

- ^ E.g. compare John Ravenhill's 2005 edition of Global Political Economy with the edition published in December 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Benjamin J. (2008). International Political Economy: An Intellectual History. Princeton University Press.

- ^ New Political Economy Symposium: The ‘British School' of International Political Economy Volume 14, Issue 3, September 2009

- ^ "Not So Quiet on the Western Front: The American School of IPE". Review of International Political Economy, Volume 16 Issue 1 2009

- ^ The 2008 Warwick RIPE Debate: ‘American’ versus ‘British’ IPE

Further reading

- Broome, André (2014) Issues and Actors in the Global Political Economy, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-28916-1.

- Cohen, Benjamin (2008). International Political Economy: An Intellectual History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13569-4.

- Gill, Stephen (1988). Global Political Economy: perspectives, problems and policies. New York: Harvester. ISBN 0-7450-0265-X.

- Gilpin, Robert (2001). Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order. Pon, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08677-X.

- Paquin, Stephane (2016), Theories of International Political Economy, Oxford University press, Don Mill, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199018963

- Phillips, Nicola, ed. (2005). Globalizing International Political Economy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-96504-7.

- Ravenhill, John (2005). Global Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926584-4.

- Watson, Matthew (2005). Foundations of International Political Economy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-1351-7.