John Coleman (Australian footballer)

| John Coleman | |||

|---|---|---|---|

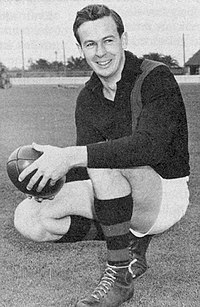

Coleman, 1949 | |||

| Personal information | |||

| Full name | John Douglas Coleman | ||

| Date of birth | 23 November 1928 | ||

| Place of birth | Port Fairy, Victoria | ||

| Date of death | 5 April 1973 (aged 44) | ||

| Place of death | Dromana, Victoria | ||

| Original team(s) | Hastings | ||

| Height | 185 cm (6 ft 1 in) | ||

| Weight | 80 kg (176 lb) | ||

| Position(s) | Full-forward | ||

| Playing career1 | |||

| Years | Club | Games (Goals) | |

| 1949–1954 | Essendon | 98 (537) | |

| Coaching career | |||

| Years | Club | Games (W–L–D) | |

| 1961–1967 | Essendon | 134 (91–40–3) | |

|

1 Playing statistics correct to the end of 1967. | |||

| Career highlights | |||

| |||

| Sources: AFL Tables, AustralianFootball.com | |||

John Douglas Coleman (23 November 1928 – 5 April 1973) was an Australian rules footballer who played for and coached the Essendon Football Club in the Victorian Football League (VFL).

Coleman is widely regarded as one of the greatest-ever Australian rules footballers. In a relatively short playing career, Coleman has the second-highest goal average in the history of the VFL/AFL (with 5.48), kicking 537 goals in 98 matches; he is only eclipsed by Peter Hudson (with 5.64). As of 2022, they are the only VFL/AFL players to average more than 5 goals per game He was also known for his high-flying spectacular marks, in some cases jumping cleanly over opponents. After a knee injury ended his playing career at age 25, he returned to coach Essendon to premiership success. Coleman died in 1973, at the age of 44, of sudden coronary atheroma.

In 1981, the VFL named the Coleman Medal in his honour, awarding it to the League's leading goalkicker at the end of the home-and-away rounds. In 1996 he was one of 12 inaugural Australian Football Hall of Fame inductees bestowed "Legend" status. He is the only player amongst them to have played fewer than 100 games at senior level.

Family

Born at Port Fairy in the Western District of Victoria to Albert Ernest Coleman (a manager) and his wife Ella Elizabeth (née Matthews), Coleman was the youngest of four siblings; his three older siblings were Lawna Ella, Thurla Margaret and Albert Edwin.[1]

He married his Sri Lankan wife, Reine Monica Fernando, in March 1955. They had two daughters, Anne-Marie and Jennifer.[2]

Teenage prodigy

Coleman was introduced to football at Port Fairy Higher Elementary School. During the early war years, the family moved to Melbourne, where Coleman was enrolled at Ascot Vale West State School. He later attended Moonee Ponds Central School, where he became dux of the school. At the age of 12, he already played in a local under-18 Australian rules football team.

In 1943, Coleman's mother took the children to live at Hastings on the Mornington Peninsula as her husband remained in the city to look after his business. Coleman then divided his time between Melbourne, where he was a student at University High School, and Hastings, playing on Saturdays for the local football team which competed in the Mornington Peninsula League.[2]

Essendon first invited Coleman to train at the club in 1946, but considered him too young to be able to play senior football.[3]

In the following two seasons, Coleman completed pre-season training with Essendon and played in practice matches.[4] However, both times he was sent back to Hastings, where he kicked 296 goals in 37 games over two years, including 23 in one game against Sorrento in August 1948.[5]

Instant sensation

The 1949 season was a make-or-break time for the budding forward. He again trained with Essendon, but he was frustrated by many of the senior players who ignored his leads. Coleman's potential was noted by a number of other clubs, and Richmond made an attempt to sign him. However, Essendon finally selected him for the opening-round match against Hawthorn.

From his first match, when he not only kicked a to-this-day unbeaten record of twelve goals on debut[6] — his 12 goals in the first home-and-away match of a season also equalled the Essendon record set by Ted Freyer, against Melbourne on 27 April 1935 — but he also kicked a goal with his first kick;[7] Coleman was the star player in the game, which was experiencing a boom in the immediate post-war years.

Standing 185 cm tall, with a pale complexion and slight build, the 20-year-old Coleman did not appear at all imposing. He looked listless as he stood in the goal square, often a metre behind the full-back, with his long-sleeved guernsey (number 10) rolled up to his elbows.

Then, with explosive speed,[8] Coleman would slip the guard of his opponent and sprint into open space on the lead or leap onto a pack of players to take a spectacular mark.

This innate ability to make position and his prodigious leap immediately caught the public imagination. He needed only a few opportunities to significantly influence the outcome of a game.

Later, one of his teammates, ruckman Geoff Leek, recalled one of his 1949 marks:

One day at Essendon I went for a mark but ended up a launching pad for Coleman. His feet just touched my shoulders and he took a mark with his boots above my head.

Coleman did not climb up packs. He got to those amazing heights with a spring. I am nearly 6ft 5in [viz., 195 cm] and Coleman jumped over my head, not once, but often. He did not leap sideways like an Olympic jumper, but straight up. And don't forget he had to grab the ball when he got there and land safely.

— Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.32

He usually converted from most of his set shots by way of long, flat punt kick. Notwithstanding this, however, he was also an excellent drop kick. Ted Rippon, Coleman's former business associate and vice-president of the football club, recalled that Coleman had kicked 14 goals in a match in Perth against a WA side, and six of those goals had been drop-kicked against the wind.[9]

Coleman capped his brilliant debut year in storybook fashion: he booted his one hundredth goal in the dying moments of a record Grand Final win over Carlton. As of 2022, he remains the only player to kick one hundred goals in his first year.

The next year, 1950, was his most prolific season, with Coleman kicking 120 goals despite missing one match with the flu,[11] and he was a major factor in Essendon's premiership win over North Melbourne.[12] Coleman's feat of kicking more than 100 goals in consecutive seasons had only been matched by Collingwood's Gordon Coventry, South Melbourne's Bob Pratt, and Collingwood's Ron Todd, and all three of those had done it much later in their careers when they were much older, far stronger, and much more experienced.

North Melbourne back pocket Pat Kelly said he would never forget playing against Essendon in Round 17 [of 1950].[13] The Herald's Alf Brown wrote:

Ten years from now I will remember that glorious mark John Coleman took in the last quarter of the Essendon North Melbourne game. North in a great fighting finish, drew within eight points of Essendon. Coleman, in an effort to lift his side, dashed down the field to take a spectacular mark about 70 yards (i.e., 65 metres) from goal. Kelly was in the pack over which Coleman soared. Admiring, and still astounded, Kelly told me after the match: "I looked up for the ball and all I could see was a set of football stops. They were Coleman's. He'd jumped clear over my head." Kelly is 5ft 10in (i.e., 178 cm).

— Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, pp.47–48

Essendon had beaten North Melbourne in the 1950 Second Semi-Final 11.14 (80) to 11.11 (77) when, in driving rain, and with 30 seconds remaining and with North Melbourne three points in front, North Melbourne's Jock McCorkell unexpectedly punched a ball that was already rolling out over the boundary line back into play just before it crossed the line, Coleman pounced on the ball, and passed it to Ron McEwin in the goal square. McEwin kicked the goal, and Essendon won by three points.[3] Essendon had only lost one match during the season.

In an unexpectedly one-sided Grand Final (many had thought that North Melbourne could win the rematch), with a rain-lashed third quarter, North Melbourne "went the knuckle", rather than playing football, and specifically targeted the Essendon players Dick Reynolds, Ron McEwin, Bill Snell, Bert Harper, Ted Leehane and, of course, Coleman.[14] Essendon won the Grand Final 13.14 (92) to North Melbourne's 7.12 (54) in front of a crowd of 87,601.[15]

Opposition coaches and full-backs stopped at nothing to curb Coleman's influence. In a one-on-one duel, close-checking, spoiling defenders fared best, but few could outrun him, and certainly no one could match him in the air.

Often pitted against two, or even three, opponents, Coleman's equilibrium could be upset by needling, jostling and physical contact, which often happened behind the play. Coleman's occasionally fiery temper ensured that he never backed away from a confrontation.

Harry Caspar: "the man who cost Essendon the flag"

Despite specific instructions having been given to the umpires in relation to the protection of forwards from "interference" from opposing backmen,[16] and in the absence of any sort of protection at all from the field umpires,[17] these problems with Coleman's response to the ever-increasing level of provocation, abuse, headlocks, hair-tugging,[18] and thuggery came to head quite sensationally when Coleman was reported in the last minutes of the second quarter of Essendon's last match of the 1951 home-and-away season against Carlton, at Princes Park. He was reported for striking Carlton's journeyman back-pocket ruckman Harry Caspar; Caspar was also reported for striking Coleman.[19][20]

Today, it is well established that Caspar had been niggling Coleman since the very start of the match, which included making persistent and heavy contact with a nasty boil on Coleman's neck; and that Caspar had punched Coleman twice whilst play was at the other end of the ground, immediately before Coleman retaliated; and that, apart from his reaction to Caspar's thuggery, Coleman had not been proactive in any way.[21] The match to that time had been a somewhat brutal encounter, and the crowd was highly agitated. During the match, bottles were thrown at Coleman, and as he came off the ground at half-time and walked up the players race, a Carlton fan spat at him through gaps in the cyclone wired barriers that separated the spectators from the players. Coleman snapped, and smashed the fan in the face, badly hurting his hand. He went into the Essendon rooms, shouting with rage at the total absence of any protection from the match officials, took off his jumper, and spoke of not returning to the field.

He was finally persuaded to take the field for the second half, and once on the field, he was so "full of fire" that, according to the recollection of ruckman Geoff Leek, at the time the resting in the forward-pocket, he took two of the most amazing marks that Leek had ever seen:

Coleman took off from behind, grabbed the ball feet above the pack, cleared it and landed with the ball in front of a mesmerised group of players. Then he goaled. It was sensational. I had never seen anything like it and I don't expect to see it repeated. There was only one John Coleman.

— Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.56

At the tribunal, Caspar's case was heard first.[22] Caspar was suspended for four weeks. Coleman's defence was simple: he had simply retaliated to two unprovoked punches from Caspar (for which Caspar had been suspended). The VFL at that time made no allowance for provocation, the Players' Advocate Dan Minogue was thought to have made a good case for Coleman by arguing that any man, if he were a man at all, would hit back after being hit. Both the boundary umpire, Herb Kent, and goal umpire Allen gave evidence that Coleman had retaliated only after he had been punched twice by Caspar.[23][24]

[Boundary umpire] Kent said he was in a forward pocket on the northern side of the ground when he saw Caspar strike Coleman in the vicinity of the chest. "Caspar struck Coleman a second time, and then Coleman retaliated by striking Caspar with a closed fist. He threw a hook after he had been hit twice", Kent said. "Coleman punched Caspar only because he had been provoked. I had a clear view of the incident from 40 yards." [Goal umpire] Allen said he was in the goals 15 yards away when he saw Caspar deliberately punch Coleman in the stomach. "Caspar and Coleman stood face to face, and after Caspar had thrown the right to the stomach, he followed after a pause with a right and left to Coleman's face", Allen said. "Then Coleman hit back with a right and a left. He shaped up and let go with the two punches. He had been provoked. "Coleman had been the target for punches. He had prevented himself from hitting back for a while, and if he had not put his hands up he would have got more. "Coleman was only defending himself. Had I been in the same position, I would have done exactly as he did", Allen said.

— The Age, Wednesday, 5 September 1951.

Given that those who retaliated were thought to have been given more lenient penalties than those who instigated, and given that — because Carlton were not in the finals — Caspar's penalty represented the first four home-and-home games in 1952, and given that Essendon were, indeed, playing in the 1951 finals, it was generally thought by those present at the tribunal that, if Coleman was to receive any penalty at all, he would be given no more than two weeks.[25] The chairman announced a penalty of four weeks. Many years later, the tribunal's chairman, Tom Hammond, agreed that whilst the tribunal had been technically correct in its penalty, given that "there was no precedent" for regarding retaliation as a lesser offence, that he now believed that the tribunal had been wrong and that it easily could have created such a precedent.[23]

Coleman broke down and wept with anger, disbelief and disappointment. As his friends and colleagues tried to assist Coleman from the tribunal's building, the impact of the rush of the large waiting crowd hurled Coleman against a traffic signal-box. He struck his head and collapsed on the pavement. He was eventually assisted into one of his friend's cars.[26][27][28]

Eventually, the Bombers went on, without Coleman—and with Dick Reynolds coming out of retirement as 20th man—to lose the Grand Final by eleven points, and Essendon supporters to this day blame Coleman's suspension for Essendon's failure to win its third successive premiership.

Goalless Coleman

On Saturday, 28 June 1952, in round ten of the 1952 season, at a very, very muddy (and narrow) Brunswick Street Oval,[29] Coleman played opposite the champion Fitzroy fullback Vic Chanter. In a tough, rugged match, Fitzroy 13.12 (90) beat Essendon 5.8 (38). Coleman, who would finish the 1952 season with 103 goals, did not score a goal in the match; and this was the first (and the only) time that Coleman was held goalless in his entire 98-game career. He had less than half a dozen kicks for the entire match—despite being moved to center half-forward for a while during the second quarter—and was only able to score two behinds, one of which was effected with the last scoring kick of the match.[30]

Coleman's injury

After six successive years in the finals, Essendon dropped down the ladder as an era ended. Coleman continued to be the best forward in the game, winning the VFL goalkicking by scoring 103 goals in 1952 and 97 in 1953. In the seventh game of the 1954 season, he kicked his best-ever tally of 14 goals against Fitzroy. But at Windy Hill a week later, Coleman fell heavily and dislocated his knee in what proved to be his last game. His attempts to return drew many headlines over the next two years, but, despite surgery, he was forced to concede defeat in the lead-up to the 1956 season.[31] There were revelations in early 1958 that Coleman's knee was sufficiently repaired to play on and his true reasons for not playing were unrelated to his knee.[32]

Coleman kicked 537 goals in just 98 appearances, at an average of 5.48 goals per game. At the time of his retirement, it was the highest goals-per-game average by any player, exceeding the next-best total of Bob Pratt (4.31 goals per game) by more than a goal.[33] Coleman's feats were even more impressive by virtue of the fact that he achieved them at a time when the rules of the game were less favourable to full-forwards: between 1925 and 1939, a free kick was always awarded against the last team to play the ball before it went out of bounds, which resulted in teams of the era adopting a direct game plan which favoured strong full-forwards, and it was an era which produced many of the league's heaviest goalscorers, including Pratt, Gordon Coventry, Bill Mohr and Ron Todd; however, Coleman played after the boundary throw-in had been re-introduced, resulting in more play along the wings and less prominence from full-forwards.[34][35] As of 2022, Coleman's VFL/AFL record average has been surpassed by only Peter Hudson (5.64 goals per game).

Coleman the businessman

Coleman was a capable businessman who understood the commercial potential of his fame. Football had interrupted his commerce studies at Melbourne University in 1949, but the game helped him to launch a career managing pubs.[3] Essendon vice president Ted Rippon, also an Essendon footballer before the Second World War, made him the manager of the Auburn Hotel, and their association continued when Coleman became licensee of the Essendon Hotel. Subsequently, he went into business on his own, running the West Brunswick Hotel.

He also developed media interests, writing for the Herald newspaper from 1954 and appearing as a commentator on television after its introduction in 1956.[36]

Coleman the coach

Coleman's business and family life took an unexpected turn in 1961, when Essendon – who, in recent times, were being increasingly referred to as "the Gliders", rather than "the Bombers", because of their poor performances at the business end of the season – considered replacing Dick Reynolds as coach (he had been at Essendon for 27 years, 21 as coach), and declared the coaching position open.[37] Essendon received three applications for the coaching position: 1960 coach Dick Reynolds, 1960 team captain Jack Clarke, and John Coleman (then 32 and out of football for 6 years), who had been persuaded to apply despite having no coaching experience. Coleman was not the committee's unanimous choice, with both Reynolds and Clarke receiving some support, but he received almost a two-to-one majority of the final vote.

Coleman was appointed coach on a day of mixed emotion; his father had died the day before.

Coleman's brief was to inject more vigor into the side and get them to play as Coleman had done. He proved to be a clever tactician, eschewing the histrionics of a "hot-gospelling" style, instead concentrating his efforts on quietly harnessing the individual talents of his players, expressing the view that team spirit was, to him, just as important as physical fitness for eventual team success.[38]

Coleman was unable to supervise his first training session until 6 April 1961 (the first home-and-away match was 15 April 1961), because he had come down with hepatitis on his return to Australia, following a two-month holiday with Monica in India and Sri Lanka.

After a disappointing first season when the team seemed to have trouble adjusting to his style, Coleman surprised many by leading the Bombers to the premiership in 1962. The team performed brilliantly, losing only two games for the season and crushing Carlton in the Grand Final.[3]

During his playing days, Coleman had developed a special loathing for umpires,[39] and they were often the target of his venomous tongue as a coach.

Essendon suffered a premiership hangover and finished fifth in the 1963 season. They were subsequently eliminated in the first semi-final of the 1964 finals series. Another flag followed in 1965 when Essendon achieved the rare feat of winning from fourth place.[40] With two premierships in the bag as a coach, Coleman could rest assured that his reputation was secure.

By now, though, his health had begun to cause him some concern. The knee injury prevented him from actively participating in training, and he suffered badly from thrombosis.[2] However, he reluctantly agreed to return for the 1967 season. The Bombers missed the finals, and Coleman voluntarily handed the coaching job over to Jack Clarke.

Sudden death

Coleman moved to the Mornington Peninsula, buying a rural property at Arthurs Seat and running the Dromana Hotel.

In the early hours of 5 April 1973, he died suddenly of coronary atheroma.[2] The public was stunned and saddened. He was just 44 years old.

On Saturday 7 April 1973, the opening round of the VFL season included a match held at Windy Hill between Essendon and Richmond, which in effect became a John Coleman memorial. Richmond defeated Essendon by 2 points that day, with the decisive last goal of the game kicked by Richmond's Kevin Sheedy, who would go on to be Essendon's next premiership-winning coach (1984) after Coleman.[41] After a large funeral conducted at St Thomas' Church of England, in Mount Alexander Road, Moonee Ponds (the church in which he had married), by Archdeacon Randal Hugh Deasey (1916–?) on Monday 9 April 1973, attended by many of Melbourne's sporting community, Coleman was cremated. Some 400 people packed into the church, and another 600 stood outside the church listening to the service broadcast over loudspeakers.[42]

The pallbearers included his brother Albert, his former business associate Ted Rippon, and the former Essendon full-forward Ted Fordham. The mourners included Sir Maurice Nathan and Ralph Lane from the VFL, and Essendon footballers John Birt, Russell Blew, Jack Clarke, Ken Fraser, Geoff Leek, Greg Sewell, David Shaw, John Somerville, and John Williams.[43]

His estate was sworn for probate at $280,270 (~$1.45 million in 2022 terms).![]() [44]

[44]

Legacy

- 1981: Introduction of the Coleman Medal, awarded to the highest goalkicker in the VFL/AFL.

- 1996, confirming his status as the greatest full-forward to ever play the game, Coleman was selected at full-forward in the AFL's Team of the Century, ahead of famous names such as Gordon Coventry, Bob Pratt, Jack Titus, Ron Todd, Bill Mohr, Peter McKenna, Peter Hudson,[45] Tony Lockett and Jason Dunstall.

- 1998: one of the twelve inaugural inductees into the Australian Football Hall of Fame; he was inducted as a "Legend of the Game".

- 2002: Recognized as the second greatest player to play for Essendon in the "Champions of Essendon" list,[46] second only to Dick Reynolds.

- 2005: Statue of Coleman erected outside the library in Coleman's hometown of Hastings.

- 2013: Statue of Coleman erected outside the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

- 2014: the National Film and Sound Archive discovered an unmarked can of 16 mm film of Coleman playing on Footscray fullback Herb Henderson in the 1953 semi-final, raising the known footage of Coleman in action from two minutes to six.[47]

References & Footnotes

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.3.

- ^ a b c d Coleman, John Douglas (1928–1973) Biographical Entry – Australian Dictionary of Biography Online

- ^ a b c Graeme Davison, 'Coleman, John Douglas (1928–1973)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 13, Melbourne University Press, 1993

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.17

- ^ "'Deadshot' Coleman kicks 23 goals". The Argus. Melbourne. 23 August 1948. p. 6. Retrieved 10 September 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Co-Cz". Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ Having been paid a mark by his brother Alby's former classmate Harry Beitzel, who was the central umpire that day (Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.25).

- ^ In his youth Coleman had been a superb athlete:

- "John, a school prefect and vice captain of the [University High School] athletics team, went on to become a schoolboy champion at high jump, hop, step and jump, and hurdles. One old [UHS] master declared he had enough talent to go on and become an Olympic high jumper. He was also a gifted tennis player." (Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.7)

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.137. It is not clear from the text whether Rippon was referring to either (or both) of the two Victoria-WA matches that were played in Perth in 1951, or was referring to an inter-club pre-season match between Essendon and a team from the Western Australian National Football League (WANFL).

- ^ The Sporting Globe's photographer, Gerard Reilly, was at the same match; and his photograph of Coleman's mark appeared on the front page of the Saturday, 30 May 1953 Sporting Globe. In the following issue, under the title "Coleman Makes It Look So Easy", the Sporting Globe published the entire five-frame sequence of Gerard Reilly's photographs.

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.51.

- ^ Brittingham W, Essendon Football Club Premiership Documentary, 1949 and 1950 (Melb, 1991)

- ^ 1950 VFL season#Round 17

- ^ See Mapleston (1996), pp.162–164, and Ross (1996), p.189.

- ^ 1950 VFL season#Grand Final Teams

- ^ "League defenders who "interfere" with forwards by holding on to their guernseys while play is at another part of the ground will be penalised in future matches. The League permit and umpire committee has instructed umpires and the umpires' coach to pay attention to the practice of interfering with forwards in future games. Mr. W. Brew (Essendon) told delegates at the V.F.L. permit meeting on Wednesday night that in recent matches leading forwards had been "held down" by their guernseys by full backs without justification, and often when play was at the other end of the ground. Mr. H. Clover (Carlton), a former champion forward: "That's-not a new trick. It happened to me 25 years ago!" ": Forwards to be Protected, The Argus, (Friday, 12 May 1950), p.19

- ^ At the time, there were no rules allowing for additional penalties (e.g., the current 50-metre penalty in AFL), and there would not be until the VFL introduced the "15-yard penalty" at the start of the 1955 season (Ross, 1996, p.201).

- ^ For example: Saturday's Rough Football, The Argus, (Monday, 20 August 1951), p.1; and The Coleman Incident, The Age, (Monday, 20 August 1951), p.14.

- ^ "Angry Crowd at Carlton; Bottle Misses Coleman", The Age, (Monday, 3 September 1951), p.14

- ^ For extensive details of the whole matter see Maplestone, 1996, p.166; Ross, 1996, p.192; and Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, pp.52–65.

- ^ Ross (1996, p.263)

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.94

- ^ a b Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, pp.57–58.

- ^ Jack Cannon's, The Argus, Wednesday, 5 September 1951 ([1])

- ^ "Coleman, Caspar get four weeks TRIBUNAL VERDICT SHOCKS". The Argus. Melbourne. 5 September 1951. p. 11. Retrieved 9 October 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Coleman — Caspar — and the Crowd", The Argus, (Wednesday, 5 Sept 1951), p.3.

- ^ "Coleman Suspended by Tribunal: Will Miss Final", The Age, (Wednesday, 5 Sept 1951), p.22

- ^ Cannon, J., "Tribunal Verdict Shocks", The Argus, (Wednesday, 5 Sept 1951), p.11

- ^ The Brunswick Street Oval was in such poor condition that Fitzroy named a squad of 23 players for the match and would not name the final 20 players until just before the match, on the Saturday afternoon, when the actual condition of the ground and the weather could be far more accurately appraised (Beames, P., "Tigers Wait on Weather to Decide Team", The Age, Friday, (27 June 1952), p.16).

- ^ The Argus newspaper spoke of him being "starved" by Chanter, and reported that "star Essendon forward John Coleman became a mere figurehead" (Dunn, J., "Tough Fitzroy Far Too Good", The Argus, (Monday, 30 June 1952), p.9)

- ^ Whitington (1976). Also, for an extensive coverage of the matter of the injury and its treatment, see Ackerly (11 May 2007)[2]

- ^ http://www.news.com.au/dailytelegraph/story/0,,25305169-5016140,00.html [bare URL]

- ^ "Career Totals and Averages". AFL Tables. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Ross, (1996), p.114.

- ^ Mapleston (1996), p.175.

- ^ Maplestone M, Those Magnificent Men, 1897–1987 (Melb, 1988)

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, pp.101–102; Mapleston (1996), pp. 191–192, and Ross (1996), p.217.

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah, 1997, p.102.

- ^ It was said that this hatred was so intense that he would not speak with anyone wearing a white shirt (the standard umpire's uniform of those times).

- ^ 1965 VFL season

- ^ 1973 VFL season#Round 1

- ^ A photograph taken outside the church appears at Ross (1996), p.263.

- ^ Miller, Petraitis & Jeremiah (1997), p.132.

- ^ The Herald (Melbourne), 23 Mar 1979

- ^ Hudson is the only player to exceed Coleman's average of goals per game (Whitington, R.S., The Champions, (Melbourne), 1976).

- ^ Club | Champions of Essendon | Essendon Football Club Official Website Archived 12 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Connolly, Rohan (5 June 2014). "John Coleman film find is football gold", The Age. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

Bibliography

- "Coleman in Action Again", The Age, Monday 27 April 1959), p.18.

- Ackerly, D. "Bomber grounded too soon", The Age, (11 May 2007).[4]

- Maplestone, M., Flying Higher: History of the Essendon Football Club 1872–1996, Essendon Football Club, (Melbourne), 1996. ISBN 0-9591740-2-8

- Miller, W., Petraitis, V. & Jeremiah, V., The Great John Coleman, Nivar Press, (Cheltenham), 1997. ISBN 0-646-31616-8

- Ross, J. (ed), 100 Years of Australian Football 1897–1996: The Complete Story of the AFL, All the Big Stories, All the Great Pictures, All the Champions, Every AFL Season Reported, Viking, (Ringwood), 1996. ISBN 0-670-86814-0 (Especially p. 206: "The incredible lightness of being Coleman")

- Whitington, R.S., The Champions, Macmillan, (Melbourne), 1976. ISBN 0-333-21065-4

External links

- John Coleman's playing statistics from AFL Tables

- John Coleman's coaching statistics from AFL Tables

- John Coleman at AustralianFootball.com

- Real Footy: "Bomber grounded too soon" (Doug Ackerly, 11 May 2007)

- Davison, Graeme (1993). "Coleman, John Douglas (1928–1973)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 13. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from May 2022

- Use dmy dates from June 2013

- 1928 births

- 1973 deaths

- Essendon Football Club players

- Essendon Football Club Premiership players

- Essendon Football Club coaches

- Essendon Football Club Premiership coaches

- Champions of Essendon

- Australian rules footballers from Melbourne

- Australian Football Hall of Fame inductees

- All-Australians (1953–1988)

- Crichton Medal winners

- VFL Leading Goalkicker Medal winners

- People from Port Fairy

- Two-time VFL/AFL Premiership players

- Sport Australia Hall of Fame inductees

- Two-time VFL/AFL Premiership coaches

- People educated at University High School, Melbourne