John Roseboro

| John Roseboro | |

|---|---|

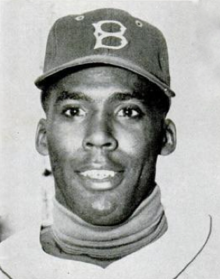

Roseboro in 1957 | |

| Catcher | |

| Born: May 13, 1933 Ashland, Ohio | |

| Died: August 16, 2002 (aged 69) Los Angeles, California | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| June 14, 1957, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 11, 1970, for the Washington Senators | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .249 |

| Home runs | 104 |

| Runs batted in | 548 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

John Junior Roseboro (May 13, 1933 – August 16, 2002) was an American professional baseball player and coach.[1] He played as a catcher in Major League Baseball from 1957 until 1970, most prominently as a member of the Los Angeles Dodgers. A four-time All-Star player, Roseboro is considered one of the best defensive catchers of the 1960s, winning two Gold Glove Awards.[2] He was the Dodgers' starting catcher in four World Series with the Dodgers winning three of those.[3] Roseboro was known for his role in one of the most violent incidents in baseball history when Juan Marichal struck him in the head with a bat during a game in 1965.[3][4]

Baseball career

Early life in professional baseball

Roseboro was born in Ashland, Ohio, and enrolled at Central State University.[5] He was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers as an amateur free agent before the 1952 season and, began his professional baseball career with the Sheboygan Indians of the Wisconsin State League.[1][6] He posted a .365 batting average with Sheboygan in 1952 to finish second in the league batting championship.[7] Roseboro missed the 1954 season due to military service but, after five years in the minor leagues, he was promoted to the major leagues in June 1957 at the age of 24.[citation needed]

Campanella's heir apparent

During his first season in the major leagues, Roseboro served as backup catcher for the Dodgers' perennial All-Star catcher Roy Campanella and was being groomed to be Campanella's replacement. However, in January 1958 he was promoted to the starting catcher's position ahead of schedule when, Campanella was injured in an automobile accident that left him paralyzed from the shoulders down and ending his athletic career.[8][9] In his first full season, with the team having moved to Los Angeles, Roseboro hit for a .271 batting average along with 14 home runs and 43 runs batted in.[1] He was also named as a reserve player for the National League in the 1958 All-Star game.[10] In 1959, Roseboro led the league's catchers in putouts and in baserunners caught stealing, helping the Dodgers win the National League Pennant.[11][12] The Dodgers went on to win the 1959 World Series, defeating the Chicago White Sox in six games.[13]

After having a below par season in 1960, Roseboro rebounded in 1961 posting career highs with 18 home runs and 59 runs batted in.[1] He also led the National League catchers in putouts and double plays and finished second in fielding percentage and in assists to earn his first Gold Glove Award when the Dodgers finished the season in second place behind the Cincinnati Reds.[14][15][16] He also earned his second All-Star team berth as a reserve player in the 1961 All-Star game.[17] He won his third All-Star berth as a reserve in the 1962 All-Star game.[18] The Dodgers battled the San Francisco Giants in a tight pennant race during the 1962 season with the two teams ending the season tied for first place and met in the 1962 National League tie-breaker series.[19] The Giants won the three-game series to clinch the National League championship.[20]

Roseboro helped guide the Dodgers' pitching staff to a league leading 2.85 earned run average in 1963 as the Dodgers clinched the National League Pennant by 6 games over the St. Louis Cardinals.[21][22] Roseboro made his presence felt in the 1963 World Series against the New York Yankees when he hit a three-run home run off Whitey Ford to win the first game of the series.[23] The Dodgers went on to win the series by defeating the Yankees in four straight games.[24] The Dodgers dropped to seventh place in the 1964 season, however Roseboro hit for a career high .287 batting average and led the league's catchers with a 60.4% caught stealing percentage, the ninth highest season percentage in major league history.[1][25][26]

Marichal incident

Roseboro was involved in a major altercation with Juan Marichal during a game between the Dodgers and San Francisco Giants at Candlestick Park on August 22, 1965.[3][27] The Giants and the Dodgers had nurtured a heated rivalry with each other dating back to their days together in the New York City market.[28] As the 1965 season neared its climax, the Dodgers were involved in a tight pennant race, entering the game leading the Milwaukee Braves by half a game and the Giants by one and a half games.[28] The incident occurred in the aftermath of the Watts riots near Roseboro's Los Angeles home and while the Dominican Civil War raged in Marichal's home country so emotions were raw.[29]

Maury Wills led off the game with a bunt single off Marichal, and eventually scored a run when Ron Fairly hit a double.[30] Marichal, a fierce competitor, viewed the bunt as a cheap way to get on base and took umbrage with Wills.[27][29] When Wills came up to bat in the second inning, Marichal threw a pitch directly at Wills, sending him sprawling to the ground.[27] Willie Mays then led off the bottom of the second inning for the Giants and Dodgers' pitcher Sandy Koufax threw a pitch over Mays' head as a token form of retaliation.[27][29] In the top of the third inning with two outs, Marichal threw a fastball that came close to hitting Fairly, prompting him to dive to the ground.[29] Marichal's act angered the Dodgers sitting in the dugout and home plate umpire Shag Crawford then warned both teams that any further retaliations would not be tolerated.[29]

Marichal came up to bat in the third inning expecting Koufax to take further retaliation against him but instead he was startled when Roseboro's return throw to Koufax after the second pitch either brushed his ear or came close enough for him to feel the breeze off the ball.[28] When Marichal confronted Roseboro about the proximity of his throw, Roseboro came out of his crouch with his fists clenched.[28] Marichal afterwards stated that he thought Roseboro was about to attack him and raised his bat, striking Roseboro at least twice over the head with it, opening a two-inch gash that sent blood flowing down the catcher's face and required 14 stitches.[28][31] Koufax raced in from the mound attempting to separate them and was joined by the umpires, players and coaches from both teams.[28]

A 14-minute brawl ensued on the field before Koufax, Giants captain Willie Mays and other peacemakers restored order.[27] Marichal was ejected from the game and afterward, National League president Warren Giles suspended him for eight games (two starts), fined him a then-NL record US $1,750[3][32] (equivalent to $16,900 in 2023),[33] and also forbade him from traveling to Dodger Stadium for the final, key two-game series of the season.[28] Roseboro filed a $110,000 damage suit against Marichal one week after the incident but eventually settled out of court for $7,500.[28]

Years later, Roseboro stated that he was retaliating for Marichal's having thrown at Wills.[28] He explained that Koufax would not throw at batters for fear of hurting them due to the velocity of his pitches.[28] He also stated that his throwing close to Marichal's ear was, "standard operating procedure", as a form of retribution.[28] Marichal didn't face the Dodgers again until spring training on April 3, 1966. In his first at bat against Marichal after the incident, Roseboro hit a three-run home run.[34] San Francisco General Manager Chub Feeney approached Dodgers General Manager Buzzy Bavasi to attempt to arrange a handshake between Marichal and Roseboro but Roseboro declined the offer.[34]

Dodger fans remained angry with Marichal for several years after the altercation and reacted unfavorably when he was signed by the Dodgers in 1975. By then, however, Roseboro had forgiven Marichal and personally appealed to fans to do the same.[35]

Later career

The Dodgers went on to win the 1965 National League Pennant by two games over the Giants. Even though the Giants won the two games against the Dodgers during which Marichal had been suspended, the outcome of the season may have been different without the Giants' pitcher's suspension, as he finished the season with a 22-13 win-loss record.[28] Roseboro once again guided the Dodgers' pitching staff to a league-leading 2.81 earned run average.[36] He caught for two twenty-game winners in 1965 with Koufax winning 26 games, while Don Drysdale won 23 games.[37] In his book, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, baseball historian Bill James said the decision to give Joe Torre a 1965 National League Gold Glove Award was absurd, stating that he was given the award because of his offensive statistics and that either Roseboro or Tom Haller was more deserving of the award.[2] In the 1965 World Series against the Minnesota Twins, Roseboro contributed 6 hits including a two-run single to win Game 3 of the series as the Dodgers went on to win the world championship in seven games.[38][39]

The Dodgers' pitching staff continued to lead the league in earned-run averages in 1966 as they battled with the San Francisco Giants and the Pittsburgh Pirates in a tight pennant race.[40] The Dodgers eventually prevailed to win the National League Pennant for a second consecutive year.[41] Roseboro led the league with a career-high 903 putouts and finished second to Joe Torre in fielding percentage to win his second Gold Glove Award.[42][43] The Dodgers would eventually lose the 1966 World Series, getting swept in four games by the Baltimore Orioles.[44]

After the Dodgers fell to 8th place, Roseboro, Ron Perranoski and Bob Miller were acquired by the Minnesota Twins, which needed a veteran catcher and left-handed reliever, in exchange for Mudcat Grant and Zoilo Versalles on November 28, 1967.[45] While with the Twins, he would be named to his fourth and final All-Star team when he was named as a reserve for the American League team in the 1969 All-Star game.[46] After the season, Roseboro was released by the Twins.[1] He signed as a free agent with the Washington Senators on December 31, 1969 but appeared in only 46 games for the last place Senators.[1] He played in his final major league game on August 11, 1970 at the age of 37.[1]

Career statistics

In a fourteen-year major league career, Roseboro played in 1,585 games, accumulating 1,206 hits in 4,847 at bats for a .249 career batting average along with 104 home runs, 548 runs batted in and an on-base percentage of .326.[1] He had a .989 career fielding percentage as a catcher. Roseboro caught 112 shutouts during his career, ranking him 19th all-time among major league catchers.[47] He was the catcher for two of Sandy Koufax's four no-hitters and caught more than 100 games in 11 of his 14 major league seasons.[4] Baseball historian Bill James ranked Roseboro 27th all-time among major league catchers.[2]

Later life

After completing his playing career with Washington, Roseboro coached for the Senators (1971) and California Angels (1972–74). Later, he served as a minor league batting instructor (1977) and catching instructor (1987) for the Dodgers. Roseboro and his wife, Barbara Fouch Roseboro, also owned a Beverly Hills public relations firm.

Roseboro appeared as a plainclothes officer in the 1966 Dragnet TV movie. He also appeared as himself in the 1962 film Experiment in Terror along with Don Drysdale and Wally Moon, and as himself in the 1963 Mister Ed episode "Leo Durocher Meets Mister Ed."[48]

Chevrolet was one of the sponsors of the Dodgers' radio coverage in the mid-1960s. The song "See the USA in Your Chevrolet", made famous by Dinah Shore in the '50s, was sung in Chevrolet commercials by Roseboro and other Dodger players. Dodger announcer Jerry Doggett once joked that Roseboro was a singer "whose singing career was destined to go absolutely nowhere."

After several years of bitterness over their famous altercation, Roseboro and Marichal became friends in the 1980s.[35] Roseboro personally appealed to the Baseball Writers' Association of America not to hold the incident against Marichal after he was passed over for election to the Hall of Fame in his first two years of eligibility. Marichal was elected in 1983, and thanked Roseboro during his induction speech.[31][49] "There were no hard feelings on my part," Roseboro said, "and I thought if that was made public, people would believe that this was really over with. So I saw him at a Dodger old-timers' game, and we posed for pictures together, and I actually visited him in the Dominican. The next year, he was in the Hall of Fame. Hey, over the years, you learn to forget things."[31]

Roseboro died of heart disease on August 16, 2002 in Los Angeles at age 69.[4] Marichal served as an honorary pallbearer at his funeral. "Johnny's forgiving me was one of the best things that happened in my life," he said, at the service. "I wish I could have had John Roseboro as my catcher."[50]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "John Roseboro at Baseball Reference". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c James, Bill (2001). The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Free Press. p. 392. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- ^ a b c d Goldstein, Richard (August 20, 2002). "John Roseboro, a Dodgers Star, Dies at 69". New York Times. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c "John Roseboro Dies". The Spokesman Review. Los Angeles Times. August 20, 2002. p. C5. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Meet A Dodger". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. March 1, 1959. p. 17. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "John Roseboro minor league statistics". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1952 Wisconsin State League Batting Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Scouts Rave Over New Campy In Praising John Roseboro". Washington Afro-American. ANP. February 5, 1957. p. 13. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "John Roseboro Is Learning Fast As Replacement For Roy Campanella". The Day. March 17, 1959. p. 16. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1958 All-Star game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1959 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1959 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1959 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1961 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1961 National League Gold Glove Award winners". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1961 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1961 All-Star game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1962 All-Star game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1962 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Tiebreaker Playoff Results". ESPN.com. September 30, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ "1963 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1963 National League Team Pitching Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1963 World Series Game 1 box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1963 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1964 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Catching Better Than 50% of Base Stealers". The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Mann, Jack (August 30, 1965). "The Battle Of San Francisco". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Marichal clubbing of Roseboro an ugly side of baseball". The Times-News. Associated Press. August 22, 1990. p. 18. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Rosengren, John (2014). "Marichal, Roseboro and the inside story of baseball's nastiest brawl". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "August 22, 1965 Dodgers-Giants box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Put up your dukes". espn.go.com. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ "MLBN Remembers ("Incident at Candlestick")". MLBN-tv. November 17, 2011.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "John Roseboro Hammers Homer In First Meeting With Juan Marichal". The Day. Associated Press. April 4, 1966. p. 25. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ a b "Baseball Boiling Over: 25 Years After Juan Marichal Clubbed John Roseboro". Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. August 21, 1990. p. B1. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1965 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1965 Los Angeles Dodgers Batting, Pitching, & Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "1965 World Series Game 3 box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1965 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1966 National League Team Pitching Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1966 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1966 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1966 National League Gold Glove Award winners". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "1966 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Joyce, Dick. "L.A. Trades Roseboro to Twins," United Press International (UPI), Wednesday, November 29, 1967. Retrieved April 18, 2020

- ^ "1969 All-Star game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "The Encyclopedia of Catchers - Trivia December 2010 - Career Shutouts Caught". The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ "John Roseboro". imdb. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman. ISBN 0-7611-3943-5.

- ^ Plaschke, Bill (August 22, 2015). "Fifty years after Giants' Juan Marichal hit Dodgers' John Roseboro with a bat, all is forgiven".

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- John Roseboro at SABR (Baseball BioProject)

- John Roseboro at Baseball Biography

- John Roseboro at Pura Pelota (Venezuelan Professional Baseball League)

- 1933 births

- 2002 deaths

- African-American baseball coaches

- African-American baseball players

- African-American basketball coaches

- American League All-Stars

- American military personnel of the Korean War

- Baseball players from Ohio

- Brooklyn Dodgers players

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- California Angels coaches

- Caribbean Series managers

- Cedar Rapids Raiders players

- Central State Marauders baseball players

- Great Falls Electrics players

- Gold Glove Award winners

- Leones del Caracas players

- American expatriate baseball players in Venezuela

- Los Angeles Dodgers players

- Major League Baseball catchers

- Major League Baseball controversies

- Minnesota Twins players

- Montreal Royals players

- National League All-Stars

- People from Ashland, Ohio

- Pueblo Dodgers players

- Sheboygan Indians players

- Violence in sports

- Washington Senators (1961–1971) coaches

- Washington Senators (1961–1971) players

- 20th-century African-American sportspeople

- American expatriate baseball people in the Dominican Republic

- 21st-century African-American people

- 20th-century African-American men