Cattle egret

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (November 2024) |

| Cattle egret | |

|---|---|

| |

| Breeding-plumaged adult western cattle egret (Ardea ibis) in Wakodahatchee Wetlands | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Subfamily: | Ardeinae |

| Genus: | Ardea Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species | |

|

A. ibis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

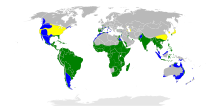

| Range of cattle egret breeding non-breeding year-round

| |

The cattle egret (formerly genus Bubulcus) is a cosmopolitan clade of heron (family Ardeidae) in the genus Ardea found in the tropics, subtropics, and warm-temperate zones. According to the IOC bird list, it contains two species, the western cattle egret and the eastern cattle egret, although some authorities regard them as a single species. Despite the similarities in plumage to the egrets of the genus Egretta, it actually belongs to the genus Ardea. Originally native to parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe, it has undergone a rapid expansion in its distribution and successfully colonised much of the rest of the world in the last century.

They are white birds adorned with buff plumes in the breeding season. They nest in colonies, usually near bodies of water and often with other wading birds. The nest is a platform of sticks in trees or shrubs. Cattle egrets exploit drier and open habitats more than other heron species. Their feeding habitats include seasonally inundated grasslands, pastures, farmlands, wetlands, and rice paddies. They often accompany cattle or other large mammals, catching insect and small vertebrate prey disturbed by these animals. Some populations are migratory and others show postbreeding dispersal.

The adult cattle egret has few predators, but birds or mammals may raid its nests, and chicks may be lost to starvation, calcium deficiency, or disturbance from other large birds. Cattle egrets maintain a special relationship with cattle, which extends to other large grazing mammals; wider human farming is believed to be a major cause of their suddenly expanded range. The cattle egret removes ticks and flies from cattle and consumes them. This benefits both organisms, but it has been implicated in the spread of tick-borne animal diseases.

Taxonomy

[edit]Before the description of the Bubulcus by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1855,[2] the western cattle egret had already been described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae as Ardea ibis,[3] and the eastern cattle egret had been described in 1783 by Pieter Boddaert as Cancroma coromanda. Their generic name Bubulcus is Latin for herdsman, referring, like the English name, to their association with cattle.[4] Ibis is a Latin and Greek word which originally referred to another white wading bird, the sacred ibis,[5] but was applied to the western cattle egret in error.[6] The epithet coromanda refers to the Coromandel Coast of India.[6]

The eastern and western cattle egrets were split by McAllan and Bruce,[7] but were regarded as conspecific by almost all other recent authors until the publication of the influential Birds of South Asia.[8] The eastern cattle egret breeds in South Asia, Eastern Asia, and Australasia, and the western species occupies the rest of the cattle egret's range, including Western Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas.[9] According to the IOC birdlist, they are both monotypic species. While some authorities recognise a third Seychelles subspecies, the Seychelles cattle egret (A. i. seychellarum), which was first described by Finn Salomonsen in 1934.[10]

Despite superficial similarities in appearance, the cattle egret is more closely related to the other members of the genus Ardea, which comprises the great or typical herons and the great egret (A. alba), than to the majority of species termed egrets in the genus Egretta.[11] Rare cases of hybridization with little blue herons (Egretta caerulea), little egrets (E. garzetta), and snowy egrets (E. thula) have been recorded.[12]

An older English name for the cattle egret is buff-backed heron.[13]

Description

[edit]

The cattle egret is a stocky heron with an 88–96 cm (34+1⁄2–38 in) wingspan; it is 46–56 cm (18–22 in) long and weighs 270–512 g (9+1⁄2–18 oz).[14] It has a relatively short, thick neck, a sturdy bill, and a hunched posture. The nonbreeding adult has mainly white plumage, a yellow bill, and greyish-yellow legs. During the breeding season, adults of the western cattle egret develop orange-buff plumes on the back, breast, and crown, and the bill, legs, and irises become bright red for a brief period prior to pairing.[15] The sexes are similar, but the male is marginally larger and has slightly longer breeding plumes than the female; juvenile birds lack coloured plumes and have a black bill.[14][16]

The eastern differs from the western in breeding plumage, when the buff colour on its head extends to the cheeks and throat, and the plumes are more golden in colour. This species' bill and tarsi are longer on average than in A. ibis.[17] A. i. seychellarum, which may or may not be a valid subspecies, is smaller and shorter-winged than the other forms. It has white cheeks and throat, like A. ibis, but the nuptial plumes are golden, as with A. coromanda.[10] Individuals with abnormally grey, melanistic plumages have been recorded.[18][19]

The positioning of the egret's eyes allows for binocular vision during feeding,[20] and physiological studies suggest that they may be capable of crepuscular or nocturnal activity.[21] Adapted to foraging on land, they have lost the ability possessed by their wetland relatives to accurately correct for light refraction by water.[22]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

The western cattle egret has undergone one of the most rapid and wide-reaching natural expansions of any bird species.[23] It was originally native to parts of southern Spain and Portugal, tropical and subtropical Africa, and humid tropical and subtropical Asia. At the end of the 19th century, it began expanding its range into southern Africa, first breeding in the Cape Province in 1908.[24] Cattle egrets were first sighted in the Americas on the boundary of Guiana and Suriname in 1877, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean.[9][14] In the 1930s, the species is thought to have become established in that area.[25] It is now widely distributed across Brazil and was first discovered in the northern region of the country in 1964, feeding along with buffalos.[26]

The species first arrived in North America in 1941 (these early sightings were originally dismissed as escapees), bred in Florida in 1953, and spread rapidly, breeding for the first time in Canada in 1962.[24] It is now commonly seen as far west as California. It was first recorded breeding in Cuba in 1957, in Costa Rica in 1958, and in Mexico in 1963, although it was probably established before then.[25] In Europe, the species had historically declined in Spain and Portugal, but in the latter part of the 20th century, it expanded back through the Iberian Peninsula, and then began to colonise other parts of Europe, southern France in 1958, northern France in 1981, and Italy in 1985.[24] Breeding in the United Kingdom was recorded for the first time in 2008, only a year after an influx seen in the previous year.[27][28] In 2008, cattle egrets were also reported as having moved into Ireland for the first time.[29] This trend has continued and cattle egrets have become more numerous in southern Britain with influxes in some numbers during the nonbreeding seasons of 2007/08 and 2016/17. They bred in Britain again in 2017, following an influx in the previous winter, and may become established there.[30][31]

In Australia, the colonisation began in the 1940s, with the eastern cattle egret establishing itself in the north and east of the continent.[32] It began to regularly visit New Zealand in the 1960s. Since 1948, the cattle egret has been permanently resident in Israel. Prior to 1948, it was only a winter visitor.[33]

The massive and rapid expansion of the cattle egret's range is due to its relationship with humans and their domesticated animals. Originally adapted to a commensal relationship with large grazing and browsing animals, it was easily able to switch to domesticated cattle and horses. As the keeping of livestock spread throughout the world, the cattle egret was able to occupy otherwise empty niches.[34] Many populations of cattle egrets are highly migratory and dispersive,[23] and this has helped the genus' range expansion. The cattle egret has been seen as a vagrant in various sub-Antarctic islands, including South Georgia, Marion Island, the South Sandwich Islands, and the South Orkney Islands.[35] A small flock of eight birds was also seen in Fiji in 2008.[36]

In addition to the natural expansion of its range, cattle egrets have been deliberately introduced into a few areas. The western cattle egret was introduced to Hawaii in 1959, and to the Chagos Archipelago in 1955. Successful releases were also made in the Seychelles and Rodrigues, but attempts to introduce them to Mauritius failed. Numerous birds were also released by Whipsnade Zoo in England, but they were never established.[37]

Although the cattle egret sometimes feeds in shallow water, unlike most herons, it is typically found in fields and dry grassy habitats, reflecting its greater dietary reliance on terrestrial insects rather than aquatic prey.[38]

Migration and movements

[edit]

Some populations of cattle egrets are migratory, others are dispersive, and distinguishing between the two can be difficult.[23] In many areas, populations can be both sedentary and migratory. In the Northern Hemisphere, migration is from cooler climes to warmer areas, but cattle egrets nesting in Australia migrate to cooler Tasmania and New Zealand in the winter and return in the spring.[32] Migration in western Africa is in response to rainfall, and in South America, migrating birds travel south of their breeding range in the nonbreeding season.[23] Populations in southern India appear to show local migrations in response to the monsoons. They move north from Kerala after September.[39][40] During winter, many birds have been seen flying at night with flocks of Indian pond herons (Ardeola grayii) on the south-eastern coast of India[41] and a winter influx has also been noted in Sri Lanka.[8]

Young birds are known to disperse up to 5,000 km (3,000 mi) from their breeding area. Flocks may fly vast distances and have been seen over seas and oceans including in the middle of the Atlantic.[42]

Ecology and behavior

[edit]Voice

[edit]The cattle egret gives a quiet, throaty rick-rack call at the breeding colony, but is otherwise largely silent.[23]

Breeding

[edit]The cattle egret nests in colonies, which are often found around bodies of water.[23] The colonies are usually found in woodlands near lakes or rivers, in swamps, or on small inland or coastal islands, and are sometimes shared with other wetland birds, such as herons, egrets, ibises, and cormorants. The breeding season varies within South Asia.[8] Nesting in northern India begins with the onset of monsoons in May.[43] The breeding season in Australia is November to early January, with one brood laid per season.[44] The North American breeding season lasts from April to October.[23] In the Seychelles, the breeding season of B. i. seychellarum is April to October.[45]

The male displays in a tree in the colony, using a range of ritualised behaviours, such as shaking a twig and sky-pointing (raising his bill vertically upwards),[46] and the pair forms over 3–4 days. A new mate is chosen in each season and when renesting following nest failure.[47] The nest is a small, untidy platform of sticks in a tree or shrub constructed by both parents. Sticks are collected by the male and arranged by the female, and stick-stealing is rife.[16] The clutch size can be one to five eggs, although three or four is most common. The pale bluish-white eggs are oval-shaped and measure 45 mm × 53 mm (1+3⁄4 in × 2 in).[44] Incubation lasts around 23 days, with both sexes sharing incubation duties.[23] The chicks are partly covered with down at hatching, but are not capable of fending for themselves; they become capable of regulating their temperature at 9–12 days and are fully feathered in 13–21 days.[48] They begin to leave the nest and climb around at 2 weeks, fledge at 30 days and become independent at around the 45th day.[47]

The cattle egret engages in low levels of brood parasitism, and a few instances have been reported of cattle egret eggs being laid in the nests of snowy egrets and little blue herons, although these eggs seldom hatch.[23] Also, evidence of low levels of intraspecific brood parasitism has been found, with females laying eggs in the nests of other cattle egrets. As much as 30% extra-pair copulations has been noted.[49][50]

The dominant factor in nesting mortality is starvation. Sibling rivalry can be intense, and in South Africa, third and fourth chicks inevitably starve.[47] In the dryer habitats with fewer amphibians, the diet may lack sufficient vertebrate content and may cause bone abnormalities in growing chicks due to calcium deficiency.[51] In Barbados, nests were sometimes raided by vervet monkeys,[9] and a study in Florida reported the fish crow and black rat as other possible nest raiders. The same study attributed some nestling mortality to brown pelicans nesting in the vicinity, which accidentally, but frequently, dislodged nests or caused nestlings to fall.[52] In Australia, Torresian crows, wedge-tailed eagles, and white-bellied sea eagles take eggs or young, and tick infestation and viral infections may also be causes of mortality.[16]

-

Cattle egret egg

-

Juvenile western cattle egret on Maui (note black bill)

Feeding

[edit]

The cattle egret feeds on a wide range of prey, particularly insects, especially grasshoppers, crickets, flies (adults and maggots), beetles, and moths, as well as spiders, frogs, fish, crayfish, small snakes, lizards and earthworms.[53][54][55][56] In a rare instance, they have been observed foraging along the branches of a banyan tree for ripe figs.[57] The cattle egret is usually found with cattle and other large grazing and browsing animals, and catches small creatures disturbed by the mammals. Studies have shown that cattle egret foraging success is much higher when foraging near a large animal than when feeding singly.[58] When foraging with cattle, it has been shown to be 3.6 times more successful in capturing prey than when foraging alone. Its performance is similar when it follows farm machinery, but it is forced to move more.[59] In urban situations, cattle egrets have also been observed foraging in peculiar situations such as railway lines.[60]

A cattle egret will weakly defend the area around a grazing animal against others of the same species, but if the area is swamped by egrets, it will give up and continue foraging elsewhere. Where numerous large animals are present, cattle egrets selectively forage around species that move at around 5–15 steps per minute, avoiding faster and slower moving herds; in Africa, cattle egrets selectively forage behind plains zebras, waterbuck, blue wildebeest and Cape buffalo.[61] Dominant birds feed nearest to the host, and thus obtain more food.[16]

The cattle egret sometimes shows versatility in its diet. On islands with seabird colonies, it will prey on the eggs and chicks of terns and other seabirds.[37] During migration, it has also been reported to eat exhausted migrating landbirds.[62] Birds of the Seychelles race also indulge in some kleptoparasitism, chasing the chicks of sooty terns and forcing them to disgorge food.[63]

Threats

[edit]Pairs of crested caracaras have been observed chasing cattle egrets in flight, forcing them to the ground, and killing them.[64]

Status

[edit]

The IUCN Red List treats them as a single species. They have a large range, with an estimated global extent of occurrence of 355,000,000 km2 (100,000,000 sq mi). Their global population is estimated to be 3.8–6.7 million individuals. For these reasons, the genus is evaluated as least concern.[1] The expansion and establishment of the genus over large ranges has led it to be classed as an invasive species, although little, if any, impact has been noted yet.[65]

Relationship with humans

[edit]As a conspicuous genus, the cattle egret has attracted many common names. These mostly relate to its habit of following cattle and other large animals, and it is known variously as cow crane, cow bird or cow heron, or even elephant bird or rhinoceros egret.[23] Its Arabic name, abu qerdan, means "father of ticks", a name derived from the huge number of parasites such as avian ticks found in its breeding colonies.[23][66] The Maasai people consider the presence of large numbers of cattle egrets as an indicator of impending drought and use it to decide on moving their cattle herds.[67]

Cattle egrets are an occurring traditional motif in fishing boats among fishermen of the Malay Peninsula east coast who believed them as a symbol of good luck and fortune.[68][69]

The cattle egret is a popular bird with cattle ranchers for its perceived role as a biocontrol of cattle parasites such as ticks and flies.[23] A study in Australia found that cattle egrets reduced the number of flies that bothered cattle by pecking them directly off the skin.[70] It was the benefit to stock that prompted ranchers and the Hawaiian Board of Agriculture and Forestry to release the western cattle egret in Hawaii.[37][71][72]

Not all interactions between humans and cattle egrets are beneficial. The cattle egret can be a safety hazard to aircraft due to its habit of feeding in large groups in the grassy verges of airports,[73] and it has been implicated in the spread of animal infections such as heartwater, infectious bursal disease,[74] and possibly Newcastle disease.[75][76]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2019). "Bubulcus ibis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22697109A155477521. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22697109A155477521.en.

- ^ Bonaparte, Charles Lucien (1855). "[untitled]". Annales des Sciences Naturelles comprenant la zoologie (in French). 4 (1): 141.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae [Stockholm]: Laurentii Salvii. p. 144.

A. capite laevi, corpore albo, rostro flavescente apice pedibusque nigris

- ^ Valpy, Francis Edward Jackson (1828). An Etymological Dictionary of the Latin Language. London; A. J. Valpy. p. 56.

- ^ "Ibis". Webster's Online Dictionary. Webster's. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ a b Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ McAllan, I.A.W.; Bruce, M.D. (1988). The birds of New South Wales, a working list. Turramurra, N.S.W.: Biocon Research Group in association with the New South Wales Bird Atlassers. ISBN 0-9587516-0-9.

- ^ a b c Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton, John C. (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. p. 58. ISBN 84-87334-67-9.

- ^ a b c Krebs, Elizabeth A.; Riven-Ramsey, Deborah; Hunte, W. (1994). "The Colonization of Barbados by Cattle Egrets (Bubulcus ibis) 1956–1990". Colonial Waterbirds. 17 (1). Waterbird Society: 86–90. doi:10.2307/1521386. JSTOR 1521386.

- ^ a b Drury, William H.; Morgan, Allen H.; Stackpole, Richard (July 1953). "Occurrence of an African Cattle Egret (Ardeola ibis ibis) in Massachusetts" (PDF). The Auk. 70 (3): 364–365. doi:10.2307/4081328. JSTOR 4081328.

- ^ Sheldon, F.H. (1987). "Phylogeny of herons estimated from DNA-DNA hybridization data". The Auk. 104 (1): 97–108. doi:10.2307/4087238. JSTOR 4087238.

- ^ McCarthy, Eugene M. (2006). Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-19-518323-1.

- ^ "Western Cattle Egret". Avibase. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "Cattle Egret". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ^ Krebs, E.A.; Hunte, W.; Green, D.J. (2004). "Plume variation, breeding performance and extra-pair copulations in the cattle egret". Behaviour. 141 (4): 479–499. doi:10.1163/156853904323066757. S2CID 35761953.

- ^ a b c d McKilligan, Neil (2005). Herons, Egrets and Bitterns: Their Biology and Conservation in Australia (PDF extract). CSIRO Publishing. pp. 88–93. ISBN 0-643-09133-5.

- ^ Biber, Jean-Pierre. "Bubulcus ibis (Linnaeus, 1758)" (PDF). Appendix 3. CITES. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ Willoughby, P. J. (2001). "Melanistic Cattle Egret". British Birds. 94: 390–391.

- ^ Herkenrath, Peter (2002). "Another melanistic cattle egret" (PDF). British Birds. 95: 531. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Martin, G.R.; Katzir, G. (1994). "Visual Fields and Eye Movements in Herons (Ardeidae)". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 44 (2): 74–85. doi:10.1159/000113571. PMID 7953610.

- ^ Rojas, L.M.; McNeil, R.; Cabana, T.; Lachapelle, P. (1999). "Behavioral, Morphological and Physiological Correlates of Diurnal and Nocturnal Vision in Selected Wading Bird Species". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 53 (5–6): 227–242. doi:10.1159/000006596. PMID 10473901. S2CID 21430848.

- ^ Katzir, G.; Strod, T.; Schectman, E.; Hareli, S.; Arad, Z. (1999). "Cattle egrets are less able to cope with light refraction than are other herons". Animal Behaviour. 57 (3): 687–694. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.1002. PMID 10196060. S2CID 11941872.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Telfair II, Raymond C. (2006). Poole, A. (ed.). "Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis)". The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.113. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c Martínez-Vilalta, A.; Motis, A. (1992). "Family Ardeidae (Herons)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A.; Sargatal, J. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Lynx Edicions. pp. 401–402. ISBN 84-87334-09-1.

- ^ a b Crosby, G. (1972). "Spread of the Cattle Egret in the Western Hemisphere" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 43 (3): 205–212. doi:10.2307/4511880. JSTOR 4511880.

- ^ Del Lama, Silvia (April 2014). "Colonization of Brazil by the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis) revealed by mitochondrial DNA". NeoBiota. 21: 49–63. doi:10.3897/neobiota.21.4966 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "First cattle egrets breed in UK". BBC News. 23 July 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ Nightingale, Barry; Dempsey, Eric (2008). "Recent reports" (PDF). British Birds. 101 (2): 108.

- ^ Barrett, Anne (15 January 2008). "Flying in ... to make new friends down on the farm". Irish Independent.

- ^ "Cattle Egrets breeding in Cheshire". Rare Bird Alert. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (29 June 2019). "Hello exotic egrets, farewell mountain butterflies as fauna revolution hits UK". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Maddock, M. (1990). "Cattle Egrets: South to Tasmania and New Zealand for the winter" (PDF). Notornis. 37 (1): 1–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Arnold, Paula (1962). Birds of Israel. Haifa, Israel: Shalit Publishers Ltd. p. 17.

- ^ Botkin, D.B. (2001). "The naturalness of biological invasions". Western North American Naturalist. 61 (3): 261–266.

- ^ Silva, M.P.; Coria, N.E.; Favero, M.; Casaux, R.J. (1995). "New Records of Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis, Blacknecked Swan Cygnus melancoryhyphus and White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis from the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica" (PDF). Marine Ornithology. 23: 65–66.

- ^ Dutson, G.; Watling, D. (2007). "Cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) and other vagrant birds in Fiji" (PDF). Notornis. 54 (4): 54–55.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Lever, C. (1987). Naturalised Birds of the World. Harlow, Essex: Longman Scientific & Technical. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0-582-46055-7.

- ^ Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterström, Dan; Grant, Peter J. (2001). Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05054-6.

- ^ Seedikkoya, K.; Azeez, P.A.; Shukkur, E.A.A. (2005). "Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis habitat use and association with cattle" (PDF). Forktail. 21: 174–176.

- ^ Kushlan, James A.; Hafner, Heinz (2000). Heron Conservation. Academic Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0-12-430130-4.

- ^ Santharam, V. (1988). "Further notes on the local movements of the Pond Heron Ardeola grayii". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 28 (1–2): 8–9.

- ^ Arendt, Wayne J. (1988). "Range Expansion of the Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) in the Greater Caribbean Basin". Colonial Waterbirds. 11 (2). Waterbird Society: 252–262. doi:10.2307/1521007. JSTOR 1521007.

- ^ Hilaluddin; Kaul, Rahul; Hussain, Mohd Shah; Imam, Ekwal; Shah, Junid N.; Abbasi, Faiza; Shawland, Tahir A. (2005). "Status and distribution of breeding cattle egret and little egret in Amroha using density method" (PDF). Current Science. 88 (25): 1239–1243.

- ^ a b Beruldsen, G. (2003). Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs. Kenmore Hills, Queensland: self. p. 182. ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

- ^ Skerrett, A.; Bullock, I.; Disley, T. (2001). Birds of the Seychelles. Helm Field Guides. ISBN 0-7136-3973-3.

- ^ Marchant, S.; Higgins, P.J. (1990). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Vol. 1 (Ratites to Ducks). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553068-3.

- ^ a b c Kushlan, James A.; Hancock, James (2005). Herons. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854981-4.

- ^ Hudson, Jack W.; Dawson, William R.; Hill, Richard W. (1974). "Growth and development of temperature regulation in nestling cattle egrets". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 49 (4): 717–720. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(74)90900-1. PMID 4154173.

- ^ Fujioka, M.; Yamagishi, S. (1981). "Extra-marital and pair copulations in cattle egret". The Auk. 98 (1): 134–144. doi:10.1093/auk/98.1.134. JSTOR 4085616.

- ^ McKilligan, N.G. (1990). "Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis)". The Auk. 107 (2): 334–341. doi:10.2307/4087617. JSTOR 4087617.

- ^ Phalen, David N.; Drew, Mark L.; Contreras, Cindy; Roset, Kimberly; Mora, Miguel (2005). "Naturally occurring secondary nutritional hyperparathyroidism in cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) from central Texas". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 41 (2): 401–415. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-41.2.401. PMID 16107676.

- ^ Maxwell, G.R. II; Kale, H.W. II (1977). "Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida". The Auk. 94 (4): 689–700. doi:10.2307/4085265. JSTOR 4085265.

- ^ Seedikkoya, K.; Azeez, P.A.; Shukkur, E.A.A. (2007). "Cattle egret as a biocontrol agent". Zoos' Print Journal. 22 (10): 2864–2866. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.1731.2864-6.

- ^ Hosein, Melinda (2012). The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago (PDF). pp. 1–4.

- ^ Siegfried, W.R. (1971). "The Food of the Cattle Egret". Journal of Applied Ecology. 8 (2). British Ecological Society: 447–468. Bibcode:1971JApEc...8..447S. doi:10.2307/2402882. JSTOR 2402882.

- ^ Fogarty, Michael J.; Hetrick, Willa Mae (1973). "Summer Foods of Cattle Egrets in North Central Florida". The Auk. 90 (2): 268–280. JSTOR 4084294.

- ^ Chaturvedi, N. (1993). "Dietary of the cattle egret Bubulcus ibis coromandus (Boddaert)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 90 (1): 90.

- ^ Grubb, T. (1976). "Adaptiveness of Foraging in the Cattle Egret". Wilson Bulletin. 88 (1): 145–148. JSTOR 4160720.

- ^ Dinsmore, James J. (1973). "Foraging Success of Cattle Egrets, Bubulcus ibis". American Midland Naturalist. 89 (1). The University of Notre Dame: 242–246. doi:10.2307/2424157. JSTOR 2424157.

- ^ Devasahayam, A. (2009). "Foraging behaviour of cattle egret in an unusual habitat". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 49 (5): 78.

- ^ Burger, J.; Gochfeld, M. (1993). "Making Foraging Decisions: Host Selection by Cattle Egrets Bubulcus ibis". Ornis Scandinavica. 24 (3). Blackwell Publishing: 229–236. doi:10.2307/3676738. JSTOR 3676738.

- ^ Cunningham, R.L. (1965). "Predation on birds by the Cattle Egret" (PDF). The Auk. 82 (3): 502–503. doi:10.2307/4083130. JSTOR 4083130. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Feare, C.J. (1975). "Scavenging and kleptoparasitism as feeding methods on Seychelles Cattle Egrets, Bubulcus ibis". Ibis. 117 (3): 388. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1975.tb04229.x.

- ^ de Godoy, Fernando Igor; Macarrão, Arthur; Costa, Julio César (June 2020). "Hunting behaviour of Southern Caracara Caracara plancus on medium-sized birds". Cotinga. 42: 28–30.

- ^ "Bubulcus ibis (bird)". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ McAtee, Waldo Lee (October 1925). "The Buff-backed Egret (Ardea ibis L., Arabic Abu Qerdan) as a Factor in Egyptian Agriculture" (PDF). The Auk. 42 (4): 603–604. doi:10.2307/4075029. JSTOR 4075029.

- ^ Tidemann, Sonia; Gosler, Andrew, eds. (2010). Ethno-ornithology: Birds, Indigenous Peoples, Culture and Society. Routledge. p. 288.

- ^ Puteh, Kijang (January 1969). "Spirits of the Bangau". The Straits Times Annual. pp. 70–1.

- ^ Noor, Farish; Khoo, Eddin (2003). Spirit of Wood: The Art of Malay Woodcarving. Periplus. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4629-0677-2.

- ^ McKilligan, N.G. (1984). "The food and feeding ecology of the Cattle Egret Ardeola ibis when nesting in south-east Queensland". Australian Wildlife Research. 11 (1): 133–144. doi:10.1071/WR9840133.

- ^ Berger, A.J. (1972). Hawaiian Birdlife. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-0213-6.

- ^ Breese, P.L. (1959). "Information on Cattle Egret, a Bird New to Hawaii". Elepaio. 20. Hawaii Audubon Society: 33–34.

- ^ Paton, P.; Fellows, D.; Tomich, P. (1986). "Distribution of Cattle Egret Roosts in Hawaii With Notes on the Problems Egrets Pose to Airports". Elepaio. 46 (13): 143–147.

- ^ Fagbohun, O.A.; Owoade, A.A.; Oluwayelu, D.O.; Olayemi, F.O. (2000). "Serological survey of infectious bursal disease virus antibodies in cattle egrets, pigeons and Nigerian laughing doves". African Journal of Biomedical Research. 3 (3): 191–192.

- ^ "Heartwater" (PDF). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ Fagbohun, O.A.; Oluwayelu, D.O.; Owoade, A.A.; Olayemi, F.O. (2000). "Survey for antibodies to Newcastle Disease virus in cattle egrets, pigeons and Nigerian laughing doves" (PDF). African Journal of Biomedical Research. 3: 193–194.

External links

[edit]- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Cattle Egret - The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Cattle egret photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)