Luby's shooting

| Luby's shooting | |

|---|---|

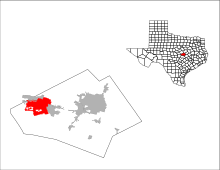

Location of Killeen, Texas | |

| Location | Killeen, Texas, US |

| Date | October 16, 1991 12:39 p.m.–12:51 p.m.[1] |

| Target | Patrons at Luby's |

Attack type | Mass shooting, mass murder, murder-suicide, shootout |

| Weapons | |

| Deaths | 24 (including the perpetrator) |

| Injured | 27 |

| Perpetrator | George Hennard |

The Luby's shooting, also known as the Luby's massacre, was a mass shooting that took place on October 16, 1991, at a Luby's Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas, United States. The perpetrator, George Hennard, drove his pickup truck through the front window of the restaurant. He quickly shot and killed 23 people, and wounded 27 others. He had a brief shootout with police, and refused their orders to surrender, fatally shooting himself.

Ranked at the time as the deadliest mass shooting in US history, by November 2017, this incident ranked as the sixth deadliest shooting in the US by a single shooter.[2]

Incident

On October 16, 1991, 35-year-old George Hennard, an unemployed man who had been in the Merchant Marine[3], drove his blue 1987 Ford Ranger pickup truck through the plate-glass front window of a Luby's Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas.[4] He yelled, "All women of Killeen and Belton are vipers! This is what you've done to me and my family! This is what Bell County did to me... this is payback day!" He then opened fire on the patrons and staff with both a 9mm Glock 17 pistol and a 9mm Ruger P89 pistol.[5][6] He stalked, shot, and killed 23 people, ten of them with single shots to the head, and wounded another 27.[4] Approximately 140 people were in the restaurant at the time.[citation needed]

It was National Boss's Day, and the cafeteria was crowded.[7][8] At first, bystanders thought the crash was an accident, but Hennard started shooting patrons almost immediately.[1] The first victim was veterinarian Michael Griffith.[9] Another patron, Tommy Vaughn, threw himself through a rear window, sustaining injuries, but he created an escape route for himself and others.[1]

Hennard reloaded at least three times before police arrived and he had a brief shootout with them. Wounded, he retreated to the bathroom. The police repeatedly told Hennard to surrender, but he refused, saying he was going to kill more people. Minutes later, he committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.[4][8]

Possible motive

Hennard was described as reclusive and belligerent, with an explosive temper. He had been pushed out of the Merchant Marine because of possession of marijuana. Numerous reports included accounts of Hennard's expressed hatred of women.[1][4][3] An ex-roommate of his said, "He hated blacks, Hispanics, gays. He said women were snakes and always had derogatory remarks about them, especially after fights with his mother."[4] Survivors from the cafeteria said Hennard had passed over men to shoot women. 14 of the 23 people killed were women, as were many of the wounded. He called two of them a "bitch" before shooting them.[4]

Victims

Murdered in the shooting were:[1]

| Name | Age | Hometown |

|---|---|---|

| Patricia Carney | 57 | Belton |

| Jimmie Caruthers | 48 | Austin |

| Kriemhild Davis | 62 | Killeen |

| Steven Dody | 43 | Copperas Cove/Fort Hood |

| Al Gratia | 71 | Copperas Cove |

| Ursula Gratia | 67 | Copperas Cove |

| Debra Gray | 33 | Copperas Cove |

| Michael Griffith | 48 | Copperas Cove |

| Venice Henehan | 70 | Metz, Missouri |

| Clodine Humphrey | 63 | Marlin |

| Sylvia King | 30 | Killeen |

| Zona Lynn | 45 | Marlin |

| Connie Peterson | 43 | Austin |

| Ruth Pujol | 55 | Copperas Cove |

| Su-Zann Rashott | 36 | Copperas Cove |

| John Romero, Jr. | 33 | Copperas Cove |

| Thomas Simmons | 55 | Copperas Cove |

| Glen Arval Spivey | 55 | Harker Heights |

| Nancy Stansbury | 44 | Harker Heights |

| Olgica Taylor | 45 | Waco |

| James Welsh | 75 | Waco |

| Lula Welsh | 64 | Waco |

| Juanita Williams | 64 | Temple |

Perpetrator

George Hennard | |

|---|---|

| File:George Hennard.jpg Hennard in 1983 | |

| Born | Georges Pierre Hennard October 15, 1956 |

| Died | October 16, 1991 (aged 35) |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Occupation | Unemployed |

| Details | |

| Date | October 16, 1991 12:39 p.m. – 12:51 p.m. (UTC-5) |

| Location(s) | Killeen, Texas |

| Killed | 23 |

| Injured | 27 |

| Weapons | Glock 17 Ruger P89 |

George Hennard was born Georges Pierre Hennard on October 15, 1956 in Sayre, Pennsylvania, the son of a Swiss-born surgeon and a homemaker.[10] He had two younger siblings, Alan and Desiree.[11] His family later moved to New Mexico, where his father worked at the White Sands Missile Range near Las Cruces. After graduating from Mayfield High School in 1974, Hennard enlisted in the U. S. Navy and served for three years, until he was honorably discharged.[12] He later worked as a merchant mariner, but was dismissed for drug use.[3]

Early in the investigation of the massacre, the Killeen police chief said that Hennard "had an evident problem with women for some reason."[3] After his parents divorced in 1983, his father moved to Houston, and his mother moved to Henderson, Nevada. The Glock 17 and Ruger P89 9mm pistols which Hennard used were purchased between February and March 1991 at a gun shop in Henderson.

Hennard stalked two sisters who lived in his neighborhood prior to the massacre. He sent them a letter, part of which said: "Please give me the satisfaction of some day laughing in the face of all those mostly white treacherous female vipers from those two towns [Killeen and Belton] who tried to destroy me and my family."[8] He also wrote that he was "truly flattered knowing I have two teenage groupie fans."[13]

Aftermath

An anti-crime bill was scheduled for a vote in the U.S. House of Representatives the day after the massacre. Some of the Hennard victims had been constituents of Representative Chet Edwards, and in response he abandoned his opposition to a gun control provision that was part of the bill.[14][15] The provision, which did not pass, would have banned some weapons and magazines like one used by Hennard.[14]

The Texas State Rifle Association and others preferred that the state allow its citizens to carry concealed weapons.[14] Democratic governor Ann Richards vetoed such bills, but in 1995 her Republican successor, George W. Bush, signed one into force.[16] The law had been campaigned for by Suzanna Hupp, who was present at the massacre; both her parents were killed by Hennard. She later testified that she would have liked to have had her gun, but said, "it was a hundred feet away in my car" (she had feared that if she was caught carrying it she might lose her chiropractor's license).[15] She testified across the country in support of concealed handgun laws, and was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1996.[17]

Hupp and another survivor of the shooting recount their experiences in detail in a 2012 episode of I Survived....[18]

A pink granite memorial stands behind the Killeen Community Center with the date of the event and the names of those killed.

Present site

The restaurant reopened five months after the massacre, but closed permanently on September 9, 2000.[19] As of 2006, a Chinese-American buffet called "Yank Sing" occupies the location.[20]

See also

- List of rampage killers (Americas)

- 2009 Fort Hood shooting and 2014 Fort Hood shooting, two other mass shootings in Killeen, Texas

- 2011 IHOP shooting, another massacre at a popular restaurant

- Brown's Chicken massacre, another massacre at a popular restaurant

- Munich shooting, another massacre at a popular restaurant

- San Ysidro McDonald's massacre, the deadliest massacre shooting in the United States prior to the Luby's shooting.[21]

References

- ^ a b c d e Jankowski, Philip (October 16, 2011). "Survivors reflect on Oct. 16, 1991, Luby's shooting". Killeen Daily Herald. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ "Las Vegas Strip shooting: The worst mass shootings in U.S. history". USA Today. October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy, J. Michael; Serrano, Richard A. (October 18, 1991). "Police May Never Learn What Motivated Gunman: Massacre: Hennard was seen as reclusive, belligerent. Officials are looking into possibility he hated women". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Chin, Paula (November 4, 1991). "A Texas Massacre". People. 36 (17). Time Inc. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Woodbury, Richard (October 28, 1991). "Crime: Ten Minutes in Hell". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Dawson, Carol (1 January 2010). House of Plenty: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Luby's Cafeterias. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 176–177. ISBN 9780292782341.

- ^ Hart, Lianne; Wood, Tracy (October 17, 1991). "23 Shot Dead at Texas Cafeteria". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Hayes, Thomas C. (October 17, 1991). "Gunman Kills 22 and Himself in Texas Cafeteria". The New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ Spellman, Jim (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood attack stirs painful memories for '91 massacre survivor". CNN. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Dawson, Carol (1 January 2010). House of Plenty: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Luby's Cafeterias. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780292782341. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ "A Texas Massacre – Vol. 36 No. 17". people.com. 1991-11-04. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ "Texas massacre had eerie link to movie 'The Fisher King'". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ Kennedy, J. Michael; Serrano, Richard A. (October 18, 1991). "Police May Never Learn What Motivated Gunman: Massacre: Hennard was seen as reclusive, belligerent. Officials are looking into possibility he hated women". Los Angeles Times. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Douglas, Carlyle C. (October 20, 1991). "Dead: 23 Texans and 1 Anti-Gun Measure". The New York Times. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Kopel, David B. (2012). "Killeen, Texas, Massacre". In Carter, Gregg Lee (ed.). Guns in American Society. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 648–650. ISBN 9780313386718. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|nopp=and|doi_brokendate=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Duggan, Paul (March 16, 2000). "Gun-Friendly Governor". Washington Post. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ "National Advisory Committee on Violence Against Women, Biographical Information" (PDF). justice.gov. June 19, 2006. p. 5. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- ^ "I Survived... - Season 4, Episode 27: Kirby, Suzanna, Raegan". TV.com. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ "Luby's in Killeen, Texas, site of 1991 massacre, closes its doors". CNN. Associated Press. 2000-09-11. Archived from the original on 2007-04-23. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Nathan, Robert (October 15, 2006). "Luby's tragedy: 15 years later". Killeen Daily Herald.

- ^ Kennedy, J. Michael; Serrano, Richard A. (October 18, 1991). "Police May Never Learn What Motivated Gunman: Massacre: Hennard was seen as reclusive, belligerent. Officials are looking into possibility he hated women". Los Angeles Times. p. 3.

Further reading

- "Shooting rampage at Killeen Luby's left 24 dead". Houston Chronicle. August 11, 2001. Archived from the original on December 1, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Winingham, Ralph (1997). "Texas massacre, fear of crime spur concealed-gun laws". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on January 28, 1999.

- 1991 in Texas

- 1991 murders in the United States

- Attacks in the United States in 1991

- Bell County, Texas

- Crimes in Texas

- Violence against women

- Deaths by firearm in Texas

- Killeen – Temple – Fort Hood metropolitan area

- Attacks on restaurants

- Mass murder in 1991

- 1991 mass shootings in the United States

- Massacres in the United States

- Murder in Texas

- Murder–suicides in Texas

- October 1991 events

- Mass shootings in Texas

- Attacks on buildings and structures in the United States