Mexican wolf

| Mexican wolf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Captive Mexican wolf running at Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | C. l. baileyi

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus baileyi (Nelson & Goldman, 1929)

| |

| |

| C. l. baileyi range | |

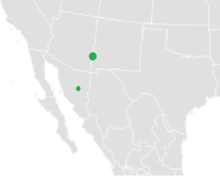

The Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), also known as the lobo,[a] is a subspecies of gray wolf native to southeastern Arizona and southern New Mexico in the United States, and northern Mexico; it also previously ranged into western Texas. It is the smallest of North America's gray wolves,[3] and is similar to the Great Plains wolf (C. l. nubilus), though it is distinguished by its smaller, narrower skull and its darker pelt, which is yellowish-gray and heavily clouded with black over the back and tail.[4] Its ancestors were likely the first gray wolves to enter North America after the extinction of the Beringian wolf, as indicated by its southern range and basal physical and genetic characteristics.[5]

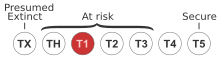

Though once held in high regard in Pre-Columbian Mexico,[6] it is the most endangered gray wolf subspecies in North America (if counting the red wolf as a separate species), having been extirpated in the wild during the mid-1900s through a combination of hunting, trapping, poisoning and digging pups from dens. After being listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1976, the United States and Mexico collaborated to capture all lobos remaining in the wild. This extreme measure prevented the lobos' extinction. Five wild Mexican wolves (four males and one pregnant female) were captured alive in Mexico from 1977 to 1980 and used to start a captive breeding program. From this program, captive-bred Mexican wolves were released into recovery areas in Arizona and New Mexico beginning in 1998 in order to assist the animals' recolonization of their former historical range.[7]

As of 2021[update], there are 186 wild Mexican wolves, and 350 in captive breeding programs, a large improvement over the 11 individuals that were released in Arizona in 1998. 2021 was the most successful year to date for the recovery program, resulting in the highest number of individuals, pups born, pups survived, and packs. Approximately 60% of total individuals were found in New Mexico and 40% in Arizona although historically on average both states have had similar amounts of wolves. In 2021, the U.S. population had nearly doubled in the past 5 years. These numbers represent the minimum amount of wolves since survey numbers only include wolf sightings confirmed by Interagency Field Team staff.[8]

Taxonomy

The Mexican wolf was first described as a distinct subspecies in 1929 by Edward Nelson and Edward Goldman on account of its small size, narrow skull and dark pelt.[9] This wolf is recognized as a subspecies of Canis lupus in the taxonomic authority Mammal Species of the World (2005).[10] In 2019, a literature review of previous studies was undertaken by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The position of the National Academies is that the historic population of Mexican wolf represents a distinct evolutionary lineage of gray wolf, and that modern Mexican wolves are their direct descendants. It is a valid taxonomic subspecies classified as Canis lupus baileyi.[11]

Lineage

Gray wolves (Canis lupus) migrated from Eurasia into North America 70,000–23,000 years ago[12][13] and gave rise to at least two morphologically and genetically distinct groups. One group is represented by the extinct Beringian wolf[12][14] and the other by the modern populations.[12] One author proposes that the Mexican wolf's ancestors were likely the first gray wolves to cross the Bering Land Bridge into North America during the Late Pleistocene after the extinction of the Beringian wolf,[14] colonizing most of the continent until pushed southwards by the newly arrived ancestors of the Great Plains wolf (C. l. nubilus).[5]

A haplotype is a group of genes found in an organism that are inherited together from one of their parents.[15][16] Mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) passes along the maternal line and can date back thousands of years.[17] A 2005 study compared the mitochondrial DNA sequences of modern wolves with those from thirty-four specimens dated between 1856 and 1915. The historic population was found to possess twice the genetic diversity of modern wolves,[18][19] which suggests that the mDNA diversity of the wolves eradicated from the western US was more than twice that of the modern population. Some haplotypes possessed by the Mexican wolf, the Great Plains wolf, and the extinct Southern Rocky Mountain wolf were found to form a unique "southern clade". All North American wolves group together with those from Eurasia, except for the southern clade which form a group exclusive to North America. The wide distribution area of the southern clade indicates that gene flow was extensive across the recognized limits of its subspecies.[19]

In 2016, a study of mitochondrial DNA sequences of both modern and ancient wolves generated a phylogenetic tree which indicated that the two most basal North American haplotypes included the Mexican wolf and the Vancouver Island wolf.[20]

In 2018, a study looked at the limb morphology of modern and fossil North American wolves. The major limb bones of the dire wolf, Beringian wolf, and most modern North American gray wolves can be clearly distinguished from one another. Late Pleistocene wolves on both sides of the Laurentide Ice Sheet — Cordilleran Ice Sheet possessed shorter legs when compared with most modern wolves. The Late Pleistocene wolves from the Natural Trap Cave, Wyoming and Rancho La Brea, southern California were similar in limb morphology to the Beringian wolves of Alaska. Modern wolves in the Midwestern USA and northwestern North America possess longer legs that evolved during the Holocene, possibly driven by the loss of slower prey. However, shorter legs survived well into the Holocene after the extinction of much of the Pleistocene megafauna, including the Beringian wolf. Holocene wolves from Middle Butte Cave (dated less than 7,600 YBP) and Moonshiner Cave (dated over 3,000 YBP) in Bingham County, Idaho were similar to the Beringian wolves. The Mexican wolf and pre-1900 samples of the Great Plains wolf resembled the Late Pleistocene and Holocene fossil gray wolves due to their shorter legs.[12]

Ancestor

In 2021, a mitochondrial DNA analysis of North American wolf-like canines indicates that the extinct Late Pleistocene Beringian wolf was the ancestor of the southern wolf clade, which includes the Mexican wolf and the Great Plains wolf. The Mexican wolf is the most ancestral of the gray wolves that live in North America today.[21]

Hybridization with coyotes and other wolves

Multiple recent studies using morphological (skull measurements) and genetic datasets have concluded that Mexican wolves hybridized in clinal fashion with other wolf subspecies where both met. The Mexican Wolf Recovery plan (2017, First Revision) currently plans to manage against such occurrence in the event that Northern Rockies and Mexican wolves come into contact to protect against a genetic swamp (i.e. genes of one group become dominant and thus result in loss of genes of another group). While the purity of Mexican wolf DNA composition is important for the time being, a natural, free-ranging wolf population on a continental scale would include hybridization between different subspecies to occur freely. Mexican wolves are under considerable threat from low genetic diversity and inbreeding because all wild Mexican wolves share on average the same amount of genes as full siblings do (all present day wild wolves are descendants of an original 7, called founders).[citation needed]

Unlike eastern wolves and red wolves, the gray wolf species rarely interbreeds with coyotes in the wild. Direct hybridizations between coyotes and gray wolves was never explicitly observed. Nevertheless, in a study that analyzed the molecular genetics of the coyotes as well as samples of historical red wolves and Mexican wolves from Texas, a few coyote genetic markers have been found in the historical samples of some isolated individual Mexican wolves. Likewise, gray wolf Y-chromosomes have also been found in a few individual male Texan coyotes.[22] This study suggested that although the Mexican gray wolf is generally less prone to hybridizations with coyotes compared to the red wolf, there may have been exceptional genetic exchanges with the Texan coyotes among a few individual gray wolves from historical remnants before the population was completely extirpated in Texas. However, the same study also countered that theory with an alternative possibility that it may have been the red wolves, who in turn also once overlapped with both species in the central Texas region, who were involved in circuiting the gene-flows between the coyotes and gray wolves much like how the eastern wolf is suspected to have bridged gene-flows between gray wolves and coyotes in the Great Lakes region since direct hybridizations between coyotes and gray wolves is considered rare.[citation needed]

In tests performed on a sample from a taxidermied carcass of what was initially labelled as a chupacabra, mitochondrial DNA analysis conducted by Texas State University professor Michael Forstner showed that it was a coyote. However, subsequent analysis by a veterinary genetics laboratory team at the University of California, Davis concluded that, based on the sex chromosomes, the male animal was a coyote–wolf hybrid sired by a male Mexican wolf.[23][24] It has been suggested that the hybrid animal was afflicted with sarcoptic mange, which would explain its hairless and blueish appearance.[23]

A study in 2018 that analyzed wolf populations suspected to have had past interactions with domestic dogs found no evidence of significant dog admixture into the Mexican wolf.[25] Another study in the same year was published in the PLOS Genetics Journal which analyzed the population genomics of gray wolves and coyotes from all over North America.[26] This study detected the presences of coyote admixtures in various western gray wolf populations, all previously thought to be free of coyote-introgression, and found that the Mexican wolves carry 10% coyote admixture. The study's author also suggests that the admixture from coyotes may have also played a role in the basal phylogenetic placement of this subspecies.

Distribution

Early accounts of the distribution of the Mexican wolf included southeastern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and western Texas in the U.S., and the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico. This past distribution is supported by ecological, morphological, and physiographic data. The areas described coincide with the distribution of the Madrean pine-oak woodlands, a habitat which supports Coues’ white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus couesi) that is the Mexican wolf's main prey.[27]

History

The Mexican wolf was held in high regard in Pre-Columbian Mexico, where it was considered a symbol of war and the Sun. In the city of Teotihuacan, it was common practice to crossbreed Mexican wolves with dogs to produce temperamental, but loyal, animal guardians. Wolves were also sacrificed in religious rituals, which involved quartering the animals and keeping their heads as attire for priests and warriors. The remaining body parts were deposited in underground funerary chambers with a westerly orientation, which symbolized rebirth, the Sun, the underworld and the canid god Xolotl.[6] The earliest written record of the Mexican wolf comes from Francisco Javier Clavijero's Historia de México in 1780, where it is referred to as Cuetzlachcojotl, and is described as being of the same species as the coyote, but with a more wolf-like pelt and a thicker neck.[28]

Decline

There was a rapid reduction of Mexican wolf populations in the Southwestern United States from 1915-1920; by the mid-1920s, livestock losses to Mexican wolves became rare in areas where the costs once ranged in the millions of dollars.[29] Vernon Bailey, writing in the early 1930s, noted that the highest Mexican wolf densities occurred in the open grazing areas of the Gila National Forest, and that wolves were completely absent in the lower Sonora. He estimated that there were 103 Mexican wolves in New Mexico in 1917, though the number had been reduced to 45 a year later. By 1927, it had apparently become extinct in New Mexico.[4] Sporadic encounters with wolves entering Texas, New Mexico and Arizona via Mexico continued through to the 1950s, until they too were driven away through traps, poison and guns. The last wild wolves to be killed in Texas were a male shot on December 5, 1970 on Cathedral Mountain Ranch and another caught in a trap on the Joe Neal Brown Ranch on December 28. Wolves were still being reported in small numbers in Arizona in the early 1970s, while accounts of the last wolf to be killed in New Mexico are difficult to evaluate, as all the purported "last wolves" could not be confirmed as genuine wolves rather than other canid species.[29]

The Mexican wolf persisted longer in Mexico, as human settlement, ranching and predator removal came later than in the Southwestern United States. Wolf numbers began to rapidly decline during the 1930s-1940s, when Mexican ranchers began adopting the same wolf-control methods as their American counterparts, relying heavily on the indiscriminate usage of 1080.[29]

Conservation and recovery

The Mexican wolf was listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 1976, with the Mexican Wolf Recovery Team being formed three years later by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.[30] The Recovery Team composed the Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, which called for the reestablishment of at least 100 wolves in their historic range through a captive breeding program. Between 1977 and 1980, four males and a pregnant female were captured in Durango and Chihuahua in Mexico to act as founders of a new "certified lineage". Three lineages were brought into the United States: McBride, Ghost Ranch and Aragón.[31] Due to the limited number of founders for each lineage, these wolves can potentially carry the risks of inbreeding.[31] However, cross-lineaged wolves have less inbreeding coefficients and greater reproductive success than purebred lineages.[31] By 1999, with the addition of new lineages, the captive Mexican wolf population throughout the US and Mexico reached 178 individuals. These captive-bred animals were subsequently released into the Apache National Forest in eastern Arizona, and allowed to recolonize east-central Arizona and south-central New Mexico, areas which were collectively termed the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area (BRWRA). The lack of livestock-free zones and tolerance for these captive wolves outside of their restoration area can be challenging for Mexican wolf conservation.[32] The Recovery Plan called for the release of additional wolves in the White Sands Wolf Recovery Area in south-central New Mexico, should the goal of 100 wild wolves in the Blue Range area not be achieved.[7]

By late 2012, it was estimated that there were at least 75 wolves and four breeding pairs living in the recovery areas, with 27% of the population consisting of pups. Since 1998, 92 wolf deaths were recorded, with four occurring in 2012; these four were all due to illegal shootings.[33] Releases have also been conducted in Mexico, and the first birth of a wild wolf litter in Mexico was reported in 2014.[34] A study released by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in February 2015 shows a minimum population of 109 wolves in 2014 in southwest New Mexico and southeast Arizona, a 31 percent increase from 2013.[35] In 2015, a court ordered the U.S. Fish and Wildlife revise the management rules.[36]

According to a survey done on the population of the Mexican wolf in Alpine, Arizona, the recovery of the species is being negatively impacted due to poaching. In an effort to fight the slowing recovery, GPS monitoring devices are being used to monitor the wolves.[37] In 2016, 14 Mexican wolves were killed, making it the highest death count of any year since they were reintroduced into the wild in 1998. Two of the deaths were caused by officials trying to collar the animals. The rest of the deaths remain under investigation.[38][39]

As of July 2017, approximately 31 wild Mexican gray wolves inhabited Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico, in the northern Sierra Madre Occidental. As of November 2017, 114 Mexican gray wolves were living in the wild in Arizona and New Mexico, distributed in 22 packs across the two states.[40] In February 2018, five more wolves were released in Chihuahua, bringing the total wild population in Mexico (Sonora and Chihuahua) to thirty-seven wolves.[41] In 2018, six Mexican wolf pups from the Endangered Wolf Center were sent to dens in Arizona and New Mexico for their survival.[42] In 2019, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services discovered that 52 of 90 wolf pups born earlier in 2018 had survived to adulthood. These new wolves brought the number of Mexican gray wolves in Arizona and New Mexico to 163, with 87 wolves in New Mexico and 76 in Arizona.[43] The 2019 census also found more than 30 in Mexico.[44]

Eight Mexican wolf cubs were born at the Desert Museum in Saltillo, Coahuila on July 1, 2020.[45] In March 2021, a family of nine Mexican gray wolves (a breeding pair of wolves and their seven pups) were released into the wild of northern Mexico, bringing the total number of wolves in Mexico to around 40 wild individuals. A 2021 census also revealed that there are now approximately 186 Mexican gray wolves in the American Southwest, with about 72 wolves in Arizona and 114 in New Mexico.[46]

Captive-born wolves may be released as a well-bonded pack consisting of a breeding pair along with their pups. Captive-born pups, who are less than 14 days old, are also released by being placed with similarly aged pups to be raised as wild wolves. In 2021, 22 pups were placed into wild dens to be raised by surrogate packs under this method known as cross-fostering.[47]

In June 2021, a year-old male Mexican gray wolf named Anubis travelled out of the Mexican Wolf Recovery Area and settled in the Coconino National Forest in central Arizona.[48] He was one of several Mexican gray wolves to have dispersed into the area over several years; the male individual may be the first permanent resident of Mexican gray wolves to settle in the Coconino National Forest.[49] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was ordered by the court to review the rule that caps the U.S. population at 325 wolves. A draft proposal is expected in the fall of 2021, but a final version is not due until July 2022.[50] In 2021, a male Mexican gray wolf was stopped from crossing from New Mexico into Mexico by a section of border wall.[51]

On March 9, 2022, two new breeding pairs of Mexican gray wolves were released into the wild in the state of Chihuahua in northern Mexico, bringing the total number of Mexican gray wolves in the country to around 45 wild individuals.[52] As of March 30, 2022, there are also now approximately 196 Mexican gray wolves living in the wild of Arizona and New Mexico.[citation needed]

Further reading

- Bass, Rick (2007), The New Wolves: The Return of the Mexican Wolf to the American Southwest, Globe Pequot. ISBN 9781599212289 (Originally published 1998)

- Holaday, B. (2003), Return of the Mexican Gray Wolf: Back to the Blue, University of Arizona Press, ISBN 0816522960

- Robinson, M. (2005), Predatory Bureaucracy: The Extermination of Wolves and the Transformation of the West, University Press of Colorado, ISBN 0870818198

- Shaw, H. (2002), The Wolf in the Southwest: The Making of an Endangered Species, High-Lonesome Books, ISBN 0944383599

- McCarthy, Cormac (1994), The Crossing, Everyman's Library Knopf, ISBN 0375407936, A poignant fictional account of a young cowboy's capture of a wolf.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "Canis lupus baileyi". explorer.natureserve.org.

- ^ "Revision to the Nonessential Experimental Population of the Mexican Wolf; Final Rule" (PDF). Federal Register. 87 (126): 39348-39373. July 1, 2022.

- ^ Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, p. 350, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ^ a b Bailey, V. (1932), Mammals of New Mexico. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Biological Survey. North American Fauna No. 53. Washington, D.C. Pages 303-308.

- ^ a b "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna. 77: 1–67. 2012. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

Note:"The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service."

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Valadez, R., Rodríguez, B., Manzanilla, L. & Tejeda, S. (2006), Dog-wolf hybrid biotype reconstruction from the archaeological city of Teotihuacan in prehispanic central Mexico Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, in Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction, ed. L. M. Snyder & E. A. Moore, pp. 121-131, Oxford, England: Oxbow Books (Proceedings of the 9th ICAZ Conference, Durham, England, 2002.

- ^ a b Nie, M. A. (2003), Beyond Wolves: The Politics of Wolf Recovery and Management, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 118-119, ISBN 0816639787

- ^ "Wild Population of Mexican Wolves Grows for Fifth Consecutive Year". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. March 12, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Nelson, E. W.; Goldman, E. A. (1929). "A new wolf from Mexico". Journal of Mammalogy. 10 (2): 165–166. doi:10.2307/1373839. JSTOR 1373839.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576

- ^ National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering (2019). Evaluating the Taxonomic Status of the Mexican Gray Wolf and the Red Wolf. doi:10.17226/25351. ISBN 978-0-309-48824-2. PMID 31211533. S2CID 134662152.

- ^ a b c d Tomiya, Susumu; Meachen, Julie A (2018). "Postcranial diversity and recent ecomorphic impoverishment of North American gray wolves". Biology Letters. 14 (1): 20170613. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0613. PMC 5803591. PMID 29343558.

- ^ Koblmüller, Stephan; Vilà, Carles; Lorente-Galdos, Belen; Dabad, Marc; Ramirez, Oscar; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Wayne, Robert K.; Leonard, Jennifer A. (2016). "Whole mitochondrial genomes illuminate ancient intercontinental dispersals of grey wolves (Canis lupus)". Journal of Biogeography. 43 (9): 1728–1738. doi:10.1111/jbi.12765. S2CID 88740690.

- ^ a b Leonard, J. A.; Vilà, C; Fox-Dobbs, K; Koch, P. L.; Wayne, R. K.; Van Valkenburgh, B (2007). "Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ecomorph" (PDF). Current Biology. 17 (13): 1146–50. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.072. hdl:10261/61282. PMID 17583509. S2CID 14039133.

- ^ Cox, C. B.; Moore, Peter D.; Ladle, Richard (2016). Biogeography: An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-118-96858-1.

- ^ Editorial Board (April 2012). Concise Dictionary of Science. V&s Publishers. ISBN 978-93-81588-64-2.

- ^ Arora, Devender; Singh, Ajeet; Sharma, Vikrant; Bhaduria, Harvendra Singh; Patel, Ram Bahadur (2015). "Hgs Db: Haplogroups Database to understand migration and molecular risk assessment". Bioinformation. 11 (6): 272–5. doi:10.6026/97320630011272. PMC 4512000. PMID 26229286.

- ^ Miklosi, Adam (2015). Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Oxford Biology (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0199545667.

- ^ a b Leonard, Jennifer A.; Vilà, Carles; Wayne, Robert K. (2004). "FAST TRACK: Legacy lost: Genetic variability and population size of extirpated US grey wolves (Canis lupus)". Molecular Ecology. 14 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02389.x. PMID 15643947. S2CID 11343074.

- ^ Ersmark, Erik; Klütsch, Cornelya F. C.; Chan, Yvonne L.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Fain, Steven R.; Illarionova, Natalia A.; Oskarsson, Mattias; Uhlén, Mathias; Zhang, Ya-Ping; Dalén, Love; Savolainen, Peter (2016). "From the Past to the Present: Wolf Phylogeography and Demographic History Based on the Mitochondrial Control Region". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00134.

- ^ Wilson, Paul J.; Rutledge, Linda Y. (2021). "Considering Pleistocene North American wolves and coyotes in the eastern Canis origin story". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (13): 9137–9147. doi:10.1002/ece3.7757. PMC 8258226. PMID 34257949.

- ^ Hailer, Frank; Leonard, Jennifer A. (2008). "Hybridization among Three Native North American Canis Species in a Region of Natural Sympatry". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3333. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3333H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003333. PMC 2556088. PMID 18841199.

- ^ a b "Texas State University Researcher Helps Unravel Mystery of Texas 'Blue Dog' Claimed to be Chupacabra". bionews-tx.com (2013-09-01)

- ^ Long, Sonny (October 31, 2008) "DNA results show chupacabra animal is mixture of coyote, Mexican wolf". Victoria Advocate.

- ^ Fitak, Robert R; Rinkevich, Sarah E; Culver, Melanie (2018). "Genome-Wide Analysis of SNPs is Consistent with No Domestic Dog Ancestry in the Endangered Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi)". Journal of Heredity. 109 (4): 372–383. doi:10.1093/jhered/esy009. PMC 6281331. PMID 29757430.

- ^ Sinding, MS; Gopalakrishan, S; Vieira, FG; Samaniego Castruita, JA; Raundrup, K; Heide Jørgensen, MP; Meldgaard, M; Petersen, B; Sicheritz-Ponten, T; Mikkelsen, JB; Marquard-Petersen, U; Dietz, R; Sonne, C; Dalén, L; Bachmann, L; Wiig, Ø; Hansen, AJ; Gilbert, MTP (2018). "Population genomics of grey wolves and wolf-like canids in North America". PLOS Genet. 14 (11): e1007745. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007745. PMC 6231604. PMID 30419012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Heffelfinger, James R; Nowak, Ronald M; Paetkau, David (2017). "Clarifying historical range to aid recovery of the Mexican wolf". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 81 (5): 766. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21252.

- ^ Clavijero, Francisco Javier (1817) The history of Mexico, Volume 1, Thomas Dobson, p. 57

- ^ a b c USFWS, (1982), Mexican wolf recovery plan, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- ^ "AZGFD: Record number of Mexican wolf pups fostered into the wild". KTAR.com. June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hedrick, P. W.; Fredrickson, R. J. (January 2008). "Captive breeding and the reintroduction of Mexican and red wolves". Molecular Ecology. 17 (1): 344–350. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03400.x. PMID 18173506. S2CID 44303787.

- ^ Povilitis, Anthony; Parsons, David R.; Robinson, Michael J.; Becker, C. Dusti (2006). "The Bureaucratically Imperiled Mexican Wolf". Conservation Biology. 20 (4): 942–945. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00489.x. ISSN 0888-8892. JSTOR 3879161. PMID 16922210. S2CID 43139520.

- ^ USFWS (2012), Mexican Wolf Recovery Program: Progress Report #15, US Fish and Wildlife Service

- ^ Gannon, M. (July 21, 2014). "First Litter of Wild Wolf Pups Born in Mexico". LiveScience. Purch. Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Humphrey, Jeff and Lambert, Lynda (February 13, 2015) 2014 Mexican Wolf Population Survey Complete - Population Exceeds 100. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- ^ Skabelund, Adrian (July 7, 2021). "Conservation groups oppose removal as wildlife managers monitor Mexican gray wolf near Flagstaff". Arizona Daily Sun. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "How Mexican gray wolves are tracked in the wild". USA Today (2016-01-28).

- ^ "CONFIRMED: 14 ENDANGERED MEXICAN GRAY WOLVES KILLED IN 2016". Gohunt. January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ "Feds: 14 endangered Mexican wolves found dead in 2016". AZCentral. January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019). "Is the Mexican Gray Wolf a Valid Subspecies?". Evaluating the Taxonomic Status of the Mexican Gray Wolf and the Red Wolf. pp. 41–50. doi:10.17226/25351. ISBN 978-0-309-48824-2. PMID 31211533. S2CID 134662152.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Liberan 5 ejemplares de lobo mexicano en Chihuahua". El Universal (in Spanish). February 9, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Clark, Patrick (April 26, 2018). "Endangered Mexican Wolf pups transferred to New Mexico and Arizona". FOX 2. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Calma, Justine (March 18, 2020). "Mexican gray wolf numbers in the US soared in 2019". The Verge. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ Pirehpour, Kevin /Cronkite (February 9, 2021). "Habitat plays crucial role in protecting two wolf groups in U.S., Mexico". Cronkite News - Arizona PBS. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "Las tiernas imágenes de los ocho cachorros de lobo gris mexicano que nacieron en Saltillo". Infobae (in European Spanish). Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Montoya Bryan, Susan (March 12, 2021). "Wild population of endangered Mexican wolves keeps growing". Yahoo News. Associated Press. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Record number of endangered Mexican gray wolf pups placed into dens to be raised by surrogate packs in Southwest U.S." KTLA. June 7, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Shumaker, Scott (August 26, 2021). "Lone Mexican wolf leaves mark in summer out west". Sedona Red Rock News. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Shumaker, Scott (June 25, 2021). "Wolf Anubis roams now-closed national forests". Sedona Red Rock News. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Botts, Lindsey (September 18, 2021). "Wildlife officials drew a line at I-40 for Mexican gray wolves, but has it hurt recovery?". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "An endangered wolf went in search of a mate. The border wall blocked him". National Geographic Society. January 21, 2022.

- ^ "Mexico releases two pairs of endangered gray wolves - Albuquerque Journal". www.abqjournal.com. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

External links

- The Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, FWS

- Mexican Gray Wolves in the Southwest USDA APHIS Wildlife Services

- Mexicanwolves.org

- NatureServe critically imperiled species

- ESA endangered species

- Subspecies of Canis lupus

- Carnivorans of North America

- Mammals of Mexico

- Mammals of the United States

- Wolves in the United States

- Fauna of Northern Mexico

- Fauna of Northeastern Mexico

- Fauna of the Southwestern United States

- Fauna of the Chihuahuan Desert

- Fauna of the Sonoran Desert

- Natural history of the Mexican Plateau

- Biota of New Mexico

- Natural history of Arizona

- Natural history of Sonora

- Mammals described in 1929

- Taxa named by Edward William Nelson

- Endangered biota of Mexico

- Endangered fauna of the United States

- Endangered fauna of North America

- Fauna of the Sierra Madre Occidental