National Day of the People's Republic of China

| National Day of the People's Republic of China 中华人民共和国国庆节 | |

|---|---|

Flower garden at Beihai Park in 2004 The signboards read 「国庆」 (guóqìng; literally "national celebration"), i.e. "National Day". | |

| Also called | China Day, China's birthday, PRC Day, 10-1 |

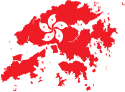

| Observed by | People's Republic of China including Hong Kong and Macau |

| Type | Historical, cultural, nationalist |

| Significance | The day of the proclamation of the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 |

| Celebrations | Festivities, including fireworks and concerts (a grand military parade every several years) |

| Date | 1 October |

| Next time | 1 October 2024 |

| Frequency | Annual |

| First time | 1 October 1949 |

| National Day of the People's Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 国庆节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 國慶節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | national celebration holiday | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

National Day (Chinese: 国庆节; pinyin: guóqìng jié; lit. 'national celebration day'), officially the National Day of the People's Republic of China (中华人民共和国国庆节), is a public holiday in China celebrated annually on 1 October as the national day of the People's Republic of China, commemorating the formal proclamation of the establishment of the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949. The Chinese Communist Party victory in the Chinese Civil War resulted in the Kuomintang "retreat" to Taiwan and the Chinese Communist Revolution whereby the People's Republic of China "replaced" the Republic of China.[1][2]

Although it is observed on 1 October, another six days are added to the official holiday, normally in lieu of the two weekend breaks around 1 October, making it a de facto public holiday comprising seven consecutive days also known as Golden Week (黄金周; huángjīn zhōu) with specifics regulated by the State Council.[3] Festivities and concerts are usually held nationwide on this day, with a grand military parade and mass pageant event held on select years.[A]

History

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) defeated the incumbent Kuomintang (KMT) nationalist government of the Republic of China in the Chinese Civil War that took place from 1927 to 1950 except for a brief alliance against Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War. In its aftermath, the nationalist government withdrew to the island of Taiwan, previously a prefecture of the Qing Empire that was ceded to Japan under its colonial rule from 1895 to 1945.

The People's Republic of China was founded on 1 October 1949, with a ceremony celebrating the forming of the Central People's Government taking place in Tiananmen Square in its new national capital of Peking (previously Peiping) on the same day that year.[5] The first public parade of the new People's Liberation Army took place there, following the address by the country's first Chairman Mao Zedong officially declaring the formal establishment of the Republic.[6] The Central People's Government passed the Resolution on the National Day of the People's Republic of China on 3 December 1949, and declared that 1 October is the National Day.

National celebrations

National Day marks the start of a Golden Week, a weeklong public holiday.[7][8][9]

The day is celebrated throughout mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau with a variety of government-organized festivities, including fireworks and concerts, as well as sports events and cultural events. Public places, such as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, are decorated in a festive theme. Portraits of revered leaders, such as Mao Zedong, are publicly displayed.[10] The Chinese government uses the celebrations to promote political goals.[11]

Wreath-laying ceremony at the Monument to the People's Heroes

From 2004 to 2013, a national wreath-laying ceremony was held on National Day in Tiananmen Square following the flag raising ceremony on years with no parades. The ceremony was centered on the Monument to the People's Heroes, built in 1958 in remembrance of the millions of Chinese who perished during the long years of national struggle. Beginning in 2014, they have been held on a new holiday, Martyrs' Day, set on the eve of National Day, 30 September, and is presided by party and state leaders.[12]

National flag-raising ceremony

In some years, a flag-raising ceremony has been held at Tiananmen Square.[13]

National civil-military parade

The special civil-military parade of the People's Liberation Army, People's Armed Police and the Militia together with representatives of the people of all walks of life including the Young Pioneers of China is held on special years in the morning of National Day itself. It has since 1984 been televised on China Central Television since 1984 (and broadcast around the world from that year as well via satellite and cable television), is a key highlight of the national celebrations in Beijing.[14] The parade was annual from 1950-59 and terminated until 1984.[15] There was a parade planned for 1989 but was cancelled following the June 4th crackdown. Parades were held again in 1999 and 2009.[16][17][18]

The parade is overseen by the president of the People's Republic of China as well as other top leadership.[18]

Censorship

Open conversation on issues related to National Day has been suppressed as the anniversary has been deemed by the Chinese government to be a sensitive event. According to Yang, the majority of Chinese social networking services sites “automatically strengthen their technical regulations and control” during the celebration despite already conducting “strict self-censorship” as required by the government.[19] Deibert et al. has said the occasion has been a target of a “just-in-time” type of content filtering, with ramifications for self-censorship and economically induced censorship.[20] Chang has said national celebrations like National Day have been enabled by the country’s “all-pervasive control system mounted by the authoritarian state.”[21] An article by the Financial Times said that while tighter internet controls were expected in preparation for China’s 60th anniversary celebration, the restrictions had still been in place “more than a month after National Day” had passed.[22]

Protests

On the mainland, protests involving National Day has been suppressed. A study by Steinhardt found that protest activity was depressed in the period both before and during the observation of "national focal events" such as National Day, which he said "strongly suggests that preemptive repression is taking place.”[23] Research by Tong and Lei found that during “crucial dates” like National Day “township officials are on duty for 24 hours, being highly alert for any potential social protest or petition visit to upper-level government.[24] An article by Wu said that “in the name of celebrating the PRC’s 60th anniversary,” the People’s Armed Police forced petitioners who had converged on Beijing to seek national-level recourse for their mistreatment by local government to “leave their own capital”.[25]

Outside the mainland, protests have been held to mark the occasion. Reasons for and factors driving the protests include the ongoing conflict between Hong Kongers and Mainlanders, the ongoing conflict between the PRC and ROC, the annexation of Tibet by China and the human rights abuses committed by the Chinese government in Xinjiang.[26][27][28]

Gallery

-

Tiananmen Square, 2006 National Day of the PRC. The placard reads "Warmly celebrate the 57th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China". The portrait is that of Sun Yat-sen.[29]

-

Military vehicles were shown in the celebration of the 50th anniversary

-

2004 National Day celebration in Tiananmen Square, Beijing

-

2008 National Day celebration in Macau

-

2012 National Day celebration in Hong Kong

See also

- National Day

- National Day of the Republic of China

- History of the People's Republic of China

- 60th anniversary of the People's Republic of China

- 70th anniversary of the People's Republic of China

Notes

References

- ^ "Flag-raising ceremony held for China's National Day celebration". Xinhua News Agency. 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Westad, Odd (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8047-4484-3.

- ^ "国务院办公厅关于2019年部分节假日安排的通知" [Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Some Holiday Arrangements in 2019]. 4 December 2018. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ 新中国历次大阅兵 [New China's previous grand military parades]. gov.cn. Xinhua News Agency. 21 August 2009. Archived from the original on 27 December 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ "China National Day: October 1st, Golden Week". travelchinaguide.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "China says National Day parade 'won't disappoint' in scale or weapons". South China Morning Post. 24 September 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "China National Day holiday 2018". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Disappointing start to 'golden week' for Hong Kong retailers". South China Morning Post. 1 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Golden Week 2022, 2023 and 2024". PublicHolidays.cn. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "China celebrates with elaborate display of power and ideology". The Irish Times. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Hung, Chang-Tai (2011). "The Politics of National Celebrations in China". In Kirby, William C (ed.). The People's Republic of China at 60 : An International Assessment. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 357–372.

Ever since the establishment of the PRC, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been noted for using mammoth celebrations to promote its political goals. Although the National Day (October 1) and May Day (May 1) parades have distinctively different purposes than the Beijing Olympic Games—the former featured annual domestic rituals of the early PRC whereas the latter was a unique international sports event—all these activities reveal a close relationship between politics and propaganda, and an all-pervasive control system mounted by the authoritarian state

- ^ "First national Martyrs' Day remembers those who sacrificed for China". South China Morning Post. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "National Day celebrated across China". Xinhua News Agency. 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ "The history of the People's Republic of China – through 70 years of mass parades". Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "The history of the People's Republic of China – through 70 years of mass parades". theconversation.com. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "1960年至1983年为什么没有国庆阅兵". Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ Hung, Chang-tai (2007). "Mao's Parades: State Spectacles in China in the 1950s" (PDF). The China Quarterly. 190 (190): 411–431. doi:10.1017/S0305741007001269. JSTOR 20192777. S2CID 154319855. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ a b Hwang, Yih-Jye; Schneider, Florian (2011). "Performance, Meaning, and Ideology in the Making of Legitimacy: The Celebrations of the People's Republic of China's Sixty-Year Anniversary". China Review. 11 (1): 27–55. ISSN 1680-2012. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Yang, Fan (2022). Habearomas, Foucault and the Political-Legal Discussions in China. Springer Nature Singapore. p. 121.

- ^ "China". Access Contested Security, Identity, and Resistance in Asian Cyberspace. The MIT Press. 2012. p. 279.

China's dynamic system of Internet control is demonstrated by the rise of "just-in- time" filtering during key events…Notable anniversaries of sensitive events are a frequent target of filtering, including the 60th anniversary of the founding of the PRC, the 20th anniversary of Tiananmen, and the first anniversary of the 2008 Tibetan protests..The combination of rigorous technical filtering mechanisms and content providers' self-policing can often lead to self-censorship, with users unwilling to risk posting controversial content. Organizations like the China Internet Illegal Information Reporting Center (CIIRC), ostensibly a civil society organization, encourage the report- ing of "illegal and harmful information" and send information about illegal content to the Ministry of Public Security. As a result, commercial Web sites can elect to prevent the posting of controversial material rather than risk negative consequences later. The pervasiveness of filtering at Internet cafés, a common method of access for many, means cafés are generally avoided for discussing sensitive topics online. Further, many users have long assumed surveillance of communication tools like TOM-Skype, thus discouraging their use.

- ^ Hung, Chang-Tai (2011). "The Politics of National Celebrations in China". In Kirby, William C (ed.). The People's Republic of China at 60 : An International Assessment. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 357–372.

Ever since the establishment of the PRC, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been noted for using mammoth celebrations to promote its political goals. Although the National Day (October 1) and May Day (May 1) parades have distinctively different purposes than the Beijing Olympic Games—the former featured annual domestic rituals of the early PRC whereas the latter was a unique international sports event—all these activities reveal a close relationship between politics and propaganda, and an all-pervasive control system mounted by the authoritarian state

- ^ Jeffries, Ian (2010). Political Develooments in Contemporary China: A Guide. Taylor & Francis. p. 452.

- ^ "Defending Stability under Threat: Sensitive Periods and the Repression of Protest in Urban China". Journal of Contemporary China. 30 (130). 533, 538: 526–549. 2021.

National focal events include the dates of the annual meetings of the NPC, the CCP Central Committee, the anniversary of the crackdown on the student movement on 4 June 1989, and National Day on 1 October...To summarize, the analysis has indicated that the number of protests is depressed before and during national focal events and after national disruptive events. Given the theoretical expectations and substantial case study evidence, this strongly suggests that preemptive repression is taking place during these periods.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Tong, Yanqi; Lei, Shaohua (2013). Social Protest in Contemporary China, 2003-2010: Transitional Pains and Regime Legitimacy. Taylor & Francis. p. 178.

- ^ Wu, Guogang (2010). "China in 2009: Muddling through Crises". Asian Survey. 50 (1). 33: 25-39.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Protesters warn of Chinese authoritarian expansion ahead of PRC National Day". Radio Free Asia.

- ^ "Protests against Beijing's policies on Hong Kong, Tibet and Xinjiang staged worldwide on China's National Day". Hong Kong Free Press.

- ^ "Global protests mark China's National Day". The Print.

- ^ Fu, Ying (16 July 2008). "China at 60: Nostalgia and progress". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

External links

- US-China Institute: 60 years of celebrating the creation of the people's republic

- images of the 2009 celebration

- Parts 1 2 3 and 4 of a documentary on the history of the Chinese National Day Parade

- The National Day Parade Official Website (2009 version)

![Tiananmen Square, 2006 National Day of the PRC. The placard reads "Warmly celebrate the 57th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China". The portrait is that of Sun Yat-sen.[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4a/Tiananmen_Square_-_National_Day_2006.jpg/160px-Tiananmen_Square_-_National_Day_2006.jpg)