Civil Disobedience (Thoreau)

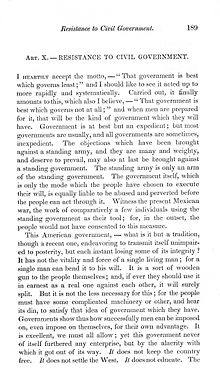

First page of "Resistance to Civil Government" as published in Aesthetic Papers, in 1849. | |

| Author | Henry David Thoreau |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | |

| Text | Civil Disobedience at Wikisource |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anarchism in the United States |

|---|

|

Resistance to Civil Government, also called On the Duty of Civil Disobedience or Civil Disobedience for short, is an essay by American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau that was first published in 1849. In it, Thoreau argues that individuals should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences, and that they have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice. Thoreau was motivated in part by his repulsion of slavery and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).

Title

[edit]| Henry David Thoreau |

|---|

|

In 1848, Thoreau gave lectures at the Concord Lyceum entitled "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government".[1] This formed the basis for his essay, which was first published under the title Resistance to Civil Government in an 1849 anthology by Elizabeth Peabody called Æsthetic Papers.[2] The latter title distinguished Thoreau's program from that of "non-resistants" or Christian anarchists like Adin Ballou and William Lloyd Garrison, as Thoreau argued that their insistence on nonresistance as praxis against the state was grossly ineffectual. Nonetheless, Thoreau was initially inspired by the Christian anarchist ideals espoused by Ballou and Garrison. Resistance also served as part of Thoreau's metaphor comparing the government to a machine: when the machine was producing injustice, it was the duty of conscientious citizens to be "a counter friction" (i.e., a resistance) "to stop the machine".[3]

In 1866, four years after Thoreau's death, the essay was reprinted in a collection of Thoreau's work (A Yankee in Canada, with Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers) under the title Civil Disobedience. Today, the essay also appears under the title On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, perhaps to contrast it with William Paley's Of the Duty of Civil Obedience to which Thoreau was in part responding. For instance, the 1960 New American Library Signet Classics edition of Walden included a version with this title. On Civil Disobedience is another common title.

The word civil has several definitions. The one that is intended in this case is "relating to citizens and their interrelations with one another or with the state", and so civil disobedience means "disobedience to the state". Sometimes people assume that civil in this case means "observing accepted social forms; polite" which would make civil disobedience something like polite, orderly disobedience. Although this is an acceptable dictionary definition of the word civil, it is not what is intended here. This misinterpretation is one reason the essay is sometimes considered to be an argument for pacifism or for exclusively nonviolent resistance. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi used this interpretation to suggest an equivalence between Thoreau's civil disobedience and his own satyagraha.[4]

Background

[edit]The slavery crisis inflamed New England in the 1840s and 1850s. The environment became especially tense after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. A lifelong abolitionist, Thoreau delivered an impassioned speech which would later become Civil Disobedience in 1848, just months after leaving Walden Pond. The speech dealt with slavery and at the same time excoriated American imperialism, particularly the Mexican–American War.[5]

Summary

[edit]Thoreau asserts that because governments are typically more harmful than helpful, they therefore cannot be justified. Democracy is no cure for this, as majorities simply by virtue of being majorities do not also gain the virtues of wisdom and justice. The judgment of an individual's conscience is not necessarily inferior to the decisions of a political body or majority, and so "[i]t is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right.... Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice."[6] He adds, "I cannot for an instant recognize as my government [that] which is the slave's government also."[7]

The government, according to Thoreau, is not just a little corrupt or unjust in the course of doing its otherwise-important work, but in fact the government is primarily an agent of corruption and injustice. Because of this, it is "not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize".[8]

Political philosophers have counseled caution about revolution because the upheaval of revolution typically causes a great deal of expense and suffering. Thoreau contends that such a cost/benefit analysis is inappropriate when the government is actively facilitating an injustice as extreme as slavery. Such a fundamental immorality justifies any difficulty or expense to bring it to an end. "This people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people."[9]

Thoreau tells his audience that they cannot blame this problem solely on pro-slavery Southern politicians, but must put the blame on those in, for instance, Massachusetts, "who are more interested in commerce and agriculture than they are in humanity, and are not prepared to do justice to the slave and to Mexico, cost what it may... There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them."[10] (See also: Thoreau's Slavery in Massachusetts which also advances this argument.)

He exhorts people not to just wait passively for an opportunity to vote for justice, because voting for justice is as ineffective as wishing for justice; what you need to do is to actually be just. This is not to say that you have an obligation to devote your life to fighting for justice, but you do have an obligation not to commit injustice and not to give injustice your practical support.

Paying taxes is one way in which otherwise well-meaning people collaborate in injustice. People who proclaim that the war in Mexico is wrong and that it is wrong to enforce slavery contradict themselves if they fund both things by paying taxes. Thoreau points out that the same people who applaud soldiers for refusing to fight an unjust war are not themselves willing to refuse to fund the government that started the war.

In a constitutional republic like the United States, people often think that the proper response to an unjust law is to try to use the political process to change the law, but to obey and respect the law until it is changed. But if the law is itself clearly unjust, and the lawmaking process is not designed to quickly obliterate such unjust laws, then Thoreau says the law deserves no respect and it should be broken. In the case of the United States, the Constitution itself enshrines the institution of slavery, and therefore falls under this condemnation. Abolitionists, in Thoreau's opinion, should completely withdraw their support of the government and stop paying taxes, even if this means courting imprisonment, or even violence.

Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.... where the State places those who are not with her, but against her,—the only house in a slave State in which a free man can abide with honor.... Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence. A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight. If the alternative is to keep all just men in prison, or give up war and slavery, the State will not hesitate which to choose. If a thousand men were not to pay their tax bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood. This is, in fact, the definition of a peaceable revolution, if any such is possible. [...] But even suppose blood should flow. Is there not a sort of blood shed when the conscience is wounded? Through this wound a man's real manhood and immortality flow out, and he bleeds to an everlasting death. I see this blood flowing now.[11]

Because the government will retaliate, Thoreau says he prefers living simply because he therefore has less to lose. "I can afford to refuse allegiance to Massachusetts.... It costs me less in every sense to incur the penalty of disobedience to the State than it would to obey. I should feel as if I were worth less in that case."[12]

He was briefly imprisoned for refusing to pay the poll tax, but even in jail felt freer than the people outside. He considered it an interesting experience and came out of it with a new perspective on his relationship to the government and its citizens. (He was released the next day when "someone interfered, and paid that tax".)[13]

Thoreau said he was willing to pay the highway tax, which went to pay for something of benefit to his neighbors, but that he was opposed to taxes that went to support the government itself—even if he could not tell if his particular contribution would eventually be spent on an unjust project or a beneficial one. "I simply wish to refuse allegiance to the State, to withdraw and stand aloof from it effectually."[14]

Because government is man-made, not an element of nature or an act of God, Thoreau hoped that its makers could be reasoned with. As governments go, he felt, the U.S. government, with all its faults, was not the worst and even had some admirable qualities. But he felt we could and should insist on better. "The progress from an absolute to a limited monarchy, from a limited monarchy to a democracy, is a progress toward a true respect for the individual.... Is a democracy, such as we know it, the last improvement possible in government? Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly."[15]

An aphorism often erroneously attributed to Thomas Jefferson,[16] "That government is best which governs least...", was actually found in Thoreau's Civil Disobedience. Thoreau was apparently paraphrasing the motto of The United States Magazine and Democratic Review: "The best government is that which governs least"[17] which might also be inspired from the 17th verse of the Tao Te Ching by Laozi: "The best rulers are scarcely known by their subjects."[18] Thoreau expanded it significantly:

I heartily accept the motto,—"That government is best which governs least;" and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which I also believe,—"That government is best which governs not at all;" and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient.

— Thoreau, Civil Disobedience[19]

Influence

[edit]Mahatma Gandhi

[edit]Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi was impressed by Thoreau's arguments. In 1907, about one year into his first satyagraha campaign in South Africa, he wrote a translated synopsis of Thoreau's argument for Indian Opinion, credited Thoreau's essay with being "the chief cause of the abolition of slavery in America", and wrote that "Both his example and writings are at present exactly applicable to the Indians in the Transvaal."[20] He later concluded:

Thoreau was a great writer, philosopher, poet, and withal a most practical man, that is, he taught nothing he was not prepared to practice in himself. He was one of the greatest and most moral men America has produced. At the time of the abolition of slavery movement, he wrote his famous essay On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. He went to gaol for the sake of his principles and suffering humanity. His essay has, therefore, been sanctified by suffering. Moreover, it is written for all time. Its incisive logic is unanswerable.

— "For Passive Resisters" (1907).[21]

Martin Luther King Jr.

[edit]American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was also influenced by this essay. In his autobiography, he wrote:

During my student days I read Henry David Thoreau's essay On Civil Disobedience for the first time. Here, in this courageous New Englander's refusal to pay his taxes and his choice of jail rather than support a war that would spread slavery's territory into Mexico, I made my first contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance. Fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system, I was so deeply moved that I reread the work several times.

I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of a legacy of creative protest. The teachings of Thoreau came alive in our civil rights movement; indeed, they are more alive than ever before. Whether expressed in a sit-in at lunch counters, a freedom ride into Mississippi, a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, these are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice.

— The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.[22]

Martin Buber

[edit]Existentialist Martin Buber wrote, of Civil Disobedience

I read it with the strong feeling that here was something that concerned me directly.... It was the concrete, the personal element, the "here and now" of this work that won me over. Thoreau did not put forth a general proposition as such; he described and established his attitude in a specific historical-biographic situation. He addressed his reader within the very sphere of this situation common to both of them in such a way that the reader not only discovered why Thoreau acted as he did at that time but also that the reader—assuming him of course to be honest and dispassionate—would have to act in just such a way whenever the proper occasion arose, provided he was seriously engaged in fulfilling his existence as a human person. The question here is not just about one of the numerous individual cases in the struggle between a truth powerless to act and a power that has become the enemy of truth. It is really a question of the absolutely concrete demonstration of the point at which this struggle at any moment becomes man's duty as man....

— "Man's Duty as Man" (1962)[23]

Others

[edit]Author Leo Tolstoy cited Civil Disobedience as having a strong impact on his nonviolence methodology. Others who are said to have been influenced by Civil Disobedience include: Suffragist Alice Paul, President John F. Kennedy, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, and various writers such as, Marcel Proust, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, Sinclair Lewis, and William Butler Yeats.[24]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Thoreau, H. D. letter to R. W. Emerson, 23 February 1848.

- ^ Thoreau, Esq., H.D. (1849). "Resistance to Civil Government". Æsthetic Papers; Edited by Elizabeth P.Peabody. Boston and New York: The Editor and G.P. Putnam. pp. 189–211. Retrieved February 1, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶18.

- ^ Rosenwald, Lawrence, The Theory, Practice & Influence of Thoreau's Civil Disobedience, quoting Gandhi, M. K., Non-Violent Resistance, pp. 3–4 and 14.

- ^ Levin, p. 29.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶4. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶7. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶8. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶9. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶10. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶22.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶24. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶33. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶36.

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶46. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ Berkes, Anna (August 28, 2014). "That government is best which governs least. (Spurious Quotation)". Th. Jefferson Monticello. Charlottesville, Virginia: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. (Monticello.org). Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Coates, Robert Eyler (1999). "The Jeffersonian Perspective: Commentary on Today's Social and Political Issues: Based on the Writings of Thomas Jefferson: "That government is best..."". Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

"That government is best which governs least" is a motto with which Henry David Thoreau opens his pamphlet, Civil Disobedience. It has been attributed to Thomas Jefferson, but no one has ever found it in any of Jefferson's writings. I think an argument can be made that it is not very likely he would ever have made such a statement, because it does not square with his views. ....

- Gillin, Joshua (September 21, 2017). "Mike Pence erroneously credits Thomas Jefferson with small government quote". PolitiFact. St. Petersburg, Florida: Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

"Thomas Jefferson said, 'Government that governs least governs best.' " — Mike Pence on Thursday, September 21st, 2017 in comments on 'Fox & Friends'

,

- Coates, Robert Eyler (1999). "The Jeffersonian Perspective: Commentary on Today's Social and Political Issues: Based on the Writings of Thomas Jefferson: "That government is best..."". Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations. 1989, Bartleby.com, accessed 20 January 2013

- ^ ""Tao Te Ching Translated by P. Merel".

- ^ ""Resistance to Civil Government" by H.D. Thoreau ("Civil Disobedience")". The Picket Line. ¶1.

- ^ Gandhi, M. K. "Duty of Disobeying Laws", Indian Opinion, 7 September and 14 September 1907.

- ^ Gandhi, M. K. "For Passive Resisters", Indian Opinion, 26 October 1907.

- ^ King, M. L. "Morehouse College" (Chapter 2 of The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.)

- ^ Buber, Martin, Man's Duty as Man from Thoreau in Our Season University of Massachusetts Press (1962) p. 19.

- ^ Maynard, W. Barksdale, Walden Pond: A History. Oxford University Press, 2005 (p. 265).

Sources

[edit]- Peabody, Elizabeth P. (ed). Aesthetic Papers. G.P. Putnam (New York, 1849). Available at the Internet Archive

External links

[edit]- A complete collection of Thoreau's essays, including Civil Disobedience at Standard Ebooks

- Full text at Project Gutenberg

Civil Disobedience public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Civil Disobedience public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Civil Disobedience by Thoreau – Britannica