Pilot ACE

| |

| Developer | National Physical Laboratory (NPL) |

|---|---|

| Release date | 1950 |

| CPU | approximately 800 vacuum tubes @ 1 megahertz |

| Memory | 128 32-bit words; later expanded to 352 words (Mercury delay lines) |

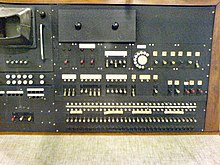

The Pilot ACE (Automatic Computing Engine) was one of the first computers built in the United Kingdom.[1] Built at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in the early 1950s, it was also one of the earliest general-purpose, stored-program computers – joining other UK designs like the Manchester Mark 1 and EDSAC of the same era. It was a preliminary version of the full ACE, which was designed by Alan Turing, who left NPL before the construction was completed.

History

Pilot ACE was built to a cut down version of Turing's full ACE design. After Turing left NPL (in part because he was disillusioned by the lack of progress on building the ACE), James H. Wilkinson took over the project. Donald Davies, Harry Huskey and Mike Woodger were involved with the design.[2][3] The Pilot ACE ran its first program on 10 May 1950,[4][5] and was demonstrated to the press in November 1950.[6][7]

Although originally intended as a prototype, it became clear that the machine was a potentially useful resource, especially given the lack of other computing devices at the time. After some upgrades to make operational use practical, it went into service in late 1951 and saw considerable operational service over the next several years. One reason Pilot ACE was useful is that it was able to perform floating-point arithmetic necessary for scientific calculations. Wilkinson tells the story of how this came to be.[8]

When first built, Pilot ACE did not have hardware for either multiplication or division, in contrast to other computers at that time. (Hardware multiplication was added later.) Pilot ACE started out using fixed-point multiplication and division implemented as software. It soon became apparent that fixed-point arithmetic was a bad idea because the numbers quickly went out of range. It only took a short time to write new software so that Pilot ACE could do floating-point arithmetic. After that, James Wilkinson became an expert and wrote a book on rounding errors in floating-point calculations, which eventually sold well.[9]

Pilot ACE used approximately 800 vacuum tubes. Its main memory consisted of mercury delay lines with an original capacity of 128 words of 32 bits each, which was later expanded to 352 words. A 4096-word drum memory was added in 1954. Its basic clock rate, 1 megahertz, was the fastest of the early British computers. The time to execute instructions was highly dependent on where they were in memory (due to the use of delay-line memory). An addition could take anywhere from 64 to 1024 microseconds.

The machine was so successful that a commercial version of it, named the DEUCE, was constructed and sold by the English Electric Company.

Pilot ACE was shut down in May 1955, and was given to the Science Museum, where it remains today.[10]

Software

Installing the magnetic drum in 1954 opened the way to develop a control program for running programs dealing with matrices. Following urging by J. M. Hahn[11][12] of the British Aircraft Corporation,[13] Brian W. Munday developed General Interpretive Programme (GIP), which required only simple codewords to run a collection of programs called "bricks". Each brick could perform a single task, such as to solve a set of simultaneous equations, to invert a matrix, and to perform matrix multiplication. Though there was nothing new in this concept, where GIP was unique was in the simplicity of the codewords that did not specify the bounds of the matrices. Bounds were taken from the matrix on the drum, where the bounds were the second and third element stored. When a matrix was punched on cards, the bounds were given as the first two elements. Thus, once a program was written, it could run automatically with different sizes of matrices, without needing to change the program. GIP was running in 1954,[14] and was re-written for DEUCE, the successor to Pilot ACE.

Bricks to be used with GIP were written by M. Woodger, who devised a unique scheme for storing array elements, namely, "block floating". To use regular floating-point would have required two words for each element. The compromise was to use a single exponent for all the elements of an array. Thus, only one word was required for each element. Only the largest element(s) were normalized. Smaller elements were scaled accordingly. Though there was some loss of precision associated with the smaller elements, it was not great, considering that elements tended to be within a factor of ten of each other. The exponent was stored with the matrix, along with the dimensions.

See also

References

- ^ Yates, David M. (1997). Turing's Legacy: A history of computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945–1995. UK: Science Museum, London. pp. 126–146. ISBN 0-901805-94-7.

- ^ Yates, David M. (1997). Turing's Legacy: A history of computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945–1995. UK: Science Museum, London. pp. 296, 300, 316. ISBN 0-901805-94-7.

- ^ Woodger, M. (1951). "Automatic Computing Engine of the National Physical Laboratory". Nature. 167 (4242): 270. Bibcode:1951Natur.167..270W. doi:10.1038/167270a0. S2CID 4286414.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin (1981). "Programming the Pilot ACE: Early Programming Activity at the National Physical Laboratory". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 3 (1). IEEE: 133–162. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1981.10015. S2CID 9711655.

- ^ Atkinson, Paul (2010). Computer. Reaktion Books. p. 39. ISBN 9781861897374.

Pilot ACE 1950.

- ^ "Automatic Computing Machinery: News – National Physical Laboratory". Mathematics of Computation. 5 (35): 174–175. 1951. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-51-99425-2. ISSN 0025-5718.

- ^ "9. The ACE Pilot Model, Teddington, England". Digital Computer Newsletter. 2 (4): 4. December 1950.[dead link]

- ^ Rota, Gian-Carlo; et al., eds. (1980). History of Computing in the Twentieth Century. Academic Press.

- ^ Wilkinson, J. H. (1994). Rounding Errors in Algebraic Processes. reprinted by Dover.

- ^ "The Pilot ACE computer". UK: Science Museum (London). Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ J. M. Hahn, Letter to M. Woodger, 20 September 1954

- ^ J. M. Hahn, "Some Suggestions for Matrix Routines for Electronic Digital Computers", September 1954

- ^ M. Campbell-Kelly, op. cit., p. 156.

- ^ M. Woodger, "The History and Present Use of Digital Computers at the National Physical Laboratory." Process Control and Automation, November 1958

Bibliography

- James H. Wilkinson, Turing's Work at the National Physical Laboratory and the Construction of Pilot ACE, DEUCE and ACE (in Nicholas Metropolis, J. Howlett, Gian-Carlo Rota, (editors), A History of Computing in the Twentieth Century, Academic Press, New York, 1980)

- Martin Campbell-Kelly, Programming the Pilot ACE (in IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 3 (No. 2), 1981, pp. 133–162)

- B. Jack Copeland (editor), Alan Turing's Automatic Computing Engine. Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-856593-3

- B. Jack Copeland, Alan Turing's Electronic Brain: The Struggle to Build the ACE, the World's Fastest Computer, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-960915-4

- Michael R. Williams, A History of Computing Technology. IEEE Computer Society Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8186-7739-2. Chap. 8.3.4.

- How Alan Turing's Pilot ACE changed computing, BBC News, 15 May 2010

Further reading

- Simon H. Lavington, Early British Computers: The Story of Vintage Computers and The People Who Built Them (Manchester University Press, 1980)

- David M. Yates, Turing's Legacy: A History of Computing at the National Physical Laboratory, 1945–1995 (Science Museum, London, 1997, ISBN 0-901805-94-7)

External links

- Oral history interview with Donald W. Davies, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Davies describes computer projects at the U.K. National Physical Laboratory, from the 1947 design work of Alan Turing to the development of the two ACE computers. Davies discusses a much larger, second ACE, and the decision to contract with English Electric Company to build the DEUCE—possibly the first commercially produced computer in Great Britain.

- The Pilot ACE in the Science Museum Group Collection

- How Alan Turing's Pilot ACE changed computing

- The world's first multi-tasking computer