Polonnaruwa

Polonnaruwa

පොළොන්නරුව பொலன்னறுவை | |

|---|---|

| |

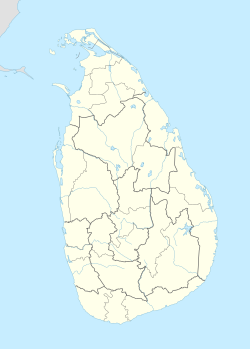

| Coordinates: 7°56′N 81°0′E / 7.933°N 81.000°E | |

| Country | Sri Lanka |

| Province | North Central Province |

| Polonnaruwa | Before 1070 AD |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (Sri Lanka Standard Time Zone) |

| Website | https://www.polonnaruwa.dist.gov.lk |

| Official name | Ancient City of Polonnaruwa |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, vi |

| Reference | 201 |

| Inscription | 1982 (6th Session) |

Poḷonnaruwa, (Template:Lang-si; Template:Lang-ta) also referred as Pulathisipura and Vijayarajapura in ancient times, is the main town of Polonnaruwa District in North Central Province, Sri Lanka. The modern town of Polonnaruwa is also known as New Town, and the other part of Polonnaruwa remains as the royal ancient city of the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa.

The second oldest of all Sri Lanka's kingdoms, Polonnaruwa was first established as a military post by the Sinhalese kingdom.[1] It was renamed Jananathamangalam by the Chola dynasty after their successful invasion of the country's then capital, Anuradhapura, in the 10th century. The Ancient City of Polonnaruwa has been declared a World Heritage Site.[2]

Modern Polonnaruwa is undergoing a major development project known as the "Awakening of Polonnaruwa," championed by former President Maithripala Sirisena. It envisions the development of all sectors in Polonnaruwa including roads, electricity, agriculture, education, health and environment.[3]

Etymology

The name Polonnaruwa is of unknown origin and was adopted by the traveller James Emerson Tennent.[4] Its Tamil form, Pulainari, is mentioned in Tamil inscriptions found at Polonnaruwa of the Chola period.[5] The name was perhaps a contraction of its ancient name Pulastya nagara or Pulatti nakaram meaning city of the Hindu sage Pulastya.[6][7]

It was renamed under Chola rule as Jananathapuram or Jananathamangalam.[8][9] The place was later known as Vijayarajapuram as mentioned in the records of Jayabahu I, which probably was derived from the name of Vijayabahu I.[10]

Demographic

Polonnaruwa has a Sinhalese majority. Muslims form the second largest group. There are also small numbers of Sri Lankan Tamils and Indian Tamils. Others include Burgher and Malay.

Ethnicity according to Polonnaruwa Town (2012)

Source:statistics.gov.lk

History

Polonnaruwa was first established as a military post by the Sinhalese kingdom.[1] And, it was renamed Jananathamangalam by the Chola dynasty after their successful invasion of the country in the 10th century.[11] Under this period systematic destruction of the Buddhist civilisation took place in the northern plains of Sri Lanka. Raja Raja Chola I built Vanavan Mahadevisvaram, a Shiva temple at Polonnaruwa named after his queen, which presently is known as Siva Devale.[12] The temple among other contained Ganesha and Parvati statues of bronze.[7] north and central parts of Sri Lanka was under this period ruled under Rajendra Chola I directly as a Chola province. However, following the year 1070 AD ended the Chola rule in the island, and Polonnaruwa was captured by Vijayabahu I of Polonnaruwa also known as Vijayabahu the great.[13]

Starting from Mahanagakula on the south of the Walawe river, Vijayabahu dispatched three armies to attack Polonnaruwa from three fronts. One army was sent along the western shore of the country to the port of Mahathittha to deal with any reinforcements arriving from South India. Afterwards, part of this army moved towards Polonnaruwa and attacked from the northwest. A second army was sent from the east across Magama to attack Polonnaruwa from the east. The third and main force advanced across the country, led by the king. Surrounded by these three armies, Polonnaruwa was besieged for seven months before king Vijayabahu’s forces entered the city. In 1070, Vijayabahu became the ruler of Polonnaruwa.[14][15] At that time Sri Lanka was known as Thambapanni.

Trade and agriculture flourished under the patronage of the famous grandson of King Vijayabahu I of Polonnaruwa, king Prakramabahu the Great, who was so adamant that no drop of water falling from the heavens was to be wasted and each was to be used toward the development of the land.[citation needed] Hence, irrigation systems that are far superior to those of the Anuradhapura Age were constructed during Parakramabahu's reign – systems which to this day supply the water necessary for paddy cultivation during the scorching dry season in the east of the country. The greatest of these systems is the Parakrama Samudra or the Sea of Parakrama which was also used as a large sea-going ship anchorage via the Mahaweli River.[13] The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was completely self-sufficient during King Parakramabahu's reign.

With the exception of his immediate successor, Nissankamalla I, the other monarchs of Polonnaruwa were not as strong-willed and were prone to picking fights within their own court.[citation needed] They also went on to form more matrimonial alliances with stronger South Indian kingdoms until these matrimonial links superseded the local royal lineage. This prompted an invasion by the Aryacakravarti dynasty warlord Kalinga Magha in 1214, which saw the complete destruction of the metropolises of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa by burning.

Present day

Today the ancient city of Polonnaruwa remains one of the best-planned archaeological relic cities in the country, standing testimony to the discipline and greatness of the Kingdom's first rulers. Its beauty was also used as a backdrop to film scenes for the Duran Duran music video Save a Prayer in 1982. The ancient city of Polonnaruwa has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Near the ancient city, there is a small town with several hotels and some glossy shops, and places to fulfil day-to-day needs. There are government institutions in a newly built area called “New Town,” about 6 km away from the town and the main road. The largest school in the district, Polonnaruwa Royal Central College is situated in the new town.

Polonnaruwa is the second largest city in North Central Province, but it is known as one of the cleanest and more beautiful cities in the country. The green environment, amazing ancient constructions, Parakrama Samudra (a huge lake built in 1200), and attractive tourist hotels and hospitable people, make it a tourism hotspot.

Another draw for tourists is the city's population of toque macaques. The monkeys have been living in the ruins since the human occupation and continued to thrive there long after the humans left.

See also

- Polonnaruwa Vatadage

- Hatadage

- Rankoth Vehera

- Nissanka Latha Mandapaya

- Gal Vihara

- World Heritage List

- Anuradhapura

- Sigiriya

- Mahawamsa

- Place names in Sri Lanka

- Statue of Parakramabahu I

- Polonnaruwa Agreement

References

- ^ a b Sastri, K. A (2000). The CōĻas. University of Madras. pp. 172–173.

- ^ "Ancient City of Polonnaruwa". World Heritage Convention, UNESCO. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ "President commences "Pibidemu Polonnaruwa" – The official website of the President of Sri Lanka". www.president.gov.lk. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Ceylon Journal of Science: Zoology & geology. Section B. University of Ceylon at the Government Press. 1904. p. 257.

- ^ Anders Hultgård, Irāmaccantiran̲ Nākacāmi, Peter Schalk (2002). Buddhism Among Tamils in Pre-colonial Tamilakam and Ilam Part 2. Department of History and Religion, University of Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell International. p. 709. ISBN 9789155453589.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society: Colombo Apothecaries Company. 1920. p. 192.

- ^ a b Dehejia, Vidya (1990-10-18). Art of the Imperial Cholas. Columbia University Press. pp. 51, 77, 86–88. ISBN 9780231515245.

- ^ Annual Report on South-Indian Epigraphy. Government of India Central Publication Branch. 1986. p. 69.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ University of Ceylon Review. Vol. 22–23. University of Ceylon. 1964. p. 69.

- ^ Archeological survey of Ceylon: Annual Report. Department of Archeology. 1909. p. 27.

- ^ Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna: Thillimalar Ragupathy. p. 185.

- ^ Man, John (1999). Atlas of the Year 1000. Harvard University Press. pp. 136. ISBN 9780674541870.

- ^ a b Nubin, Walter (2002). Sri Lanka: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Science Publishers. pp. 102, 103. ISBN 9781590335734.

- ^ "THE POLONNARUWA KINGS". Rhajiv Ratnatunga. lakdiva.org. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ "Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka".

- Balasooriya, Jayasinghe (2004). The Glory of Ancient Polonnaruva. Polonnaruva: Sooriya Printers. ISBN 955-8158-01-1 (Archeological ruins)

- 'The Satmahal Prasada: A Historic link between Lan Na and Sri Lanka', in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 1. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- Ulrich von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures of Sri Lanka, XII. Monuments of Polonnaruva: 632–677. (Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd., 1990). ISBN 962-7049-05-0 / ISBN 978-962-7049-05-0

- Ulrich von Schroeder, The Golden Age of Sculpture in Sri Lanka – Masterpieces of Buddhist and Hindu Bronzes from Museums in Sri Lanka, [catalogue of the exhibition held at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington, D. C., 1st November 1992 – 26th September 1993]. (Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd., 1992). ISBN 962-7049-06-9 / ISBN 978-962-7049-06-7