Saint Blaise

Blaise of Sebaste Սուրբ Վլասի | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hieromartyr, Holy Helper | |

| Born | 3 February (Eastern: 11 February) ? AD Sebastea, historical Lesser Armenia |

| Died | 316 AD (aged between his 30s and 40s) |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Churches Oriental Orthodox Church Anglican Communion |

| Major shrine | St Blaise's Church |

| Feast | 3 February (Catholic, Anglican Communion)

Usually in January (date varies)(Armenian Apostolic) 11 February (Eastern Orthodox and Greek Catholic) |

| Attributes | Bishop, animals, crossed candles, tending a choking boy, wool comb |

| Patronage | Infants, animals, builders, stonecutters, carvers, drapers, wool workers, wool industry, veterinarians, physicians, healing, throats, the sick, against choking, ENT illnesses, Bradford, Sicilì, Salerno, Maratea, Italy, Sicily, Dubrovnik, Ciudad del Este, Paraguay, Campanário, Madeira, Rubiera, and Sebaste, Antique. |

Blaise of Sebaste (Armenian: Սուրբ Վլասի, Surb Vlasi; Greek: Ἅγιος Βλάσιος, Hágios Blásios; Latin: Blasius martyred 316 AD) was a physician and bishop of Sebastea in historical Lesser Armenia (modern Sivas, Turkey) who is venerated as a Christian saint and martyr. He is counted as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers.

Blaise is a saint in the Catholic, Western Rite Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches and is the patron saint of wool combers and of sufferers from ENT illnesses. In the Latin Church, his feast falls on 3 February. In the Eastern Churches, it is on 11 February.[1] According to the Acta Sanctorum, he was martyred by being beaten, tortured with iron combs, and beheaded.

Early records

[edit]The first reference to Blaise is the medical writings of Aëtius Amidenus (c. AD 500) where his aid is invoked in treating patients with objects stuck in the throat.

Marco Polo reported on the place where "Messer Saint Blaise obtained the glorious crown of martyrdom", Sebastea.[2] The shrine near the citadel mount was mentioned by William of Rubruck in 1253, although the ruins are no longer visible.[3]

Life

[edit]It is said from being a healer of bodily ailments, Saint Blaise was to become an expert on souls, then he retired for a time to a cavern where he remained in prayer. As bishop of Sebastea, Blaise instructed people as much by his example as by his words, and his great virtues and his sanctity were attested by many miracles. People were said to flock to him for cures of bodily and spiritual ills.[4] He is said to have healed animals, who came to him on their own for his assistance, and in turn to have been helped by animals.

In 316 the governor of Cappadocia and Lesser Armenia, Agricola, began a persecution of him by order of the Emperor Licinius, and Blaise was seized. After his interrogation and a severe scourging, he was imprisoned[4] and subsequently beheaded.

The Acts of St. Blaise

[edit]

The legendary Acts of St. Blaise were written 400 years after his death, and are apocryphal and, possibly, fictional.[1][5]

The legend narrative is as follows:

Blaise, who had studied philosophy in his youth, was a doctor in Sebaste in Armenia, the city of his birth, who exercised his art with miraculous ability, good-will, and piety. When the bishop of the city died, he was chosen to succeed him, with the acclamation of all the people. His holiness was manifest through many miracles: from all around, people came to him to find cures for their spirit and their body; even wild animals came in herds to receive his blessing. In 316, Agricola, the governor of Cappadocia and of Lesser Armenia, having arrived in Sebastia at the order of the emperor Licinius to kill the Christians, arrested the bishop. As he was being led to jail, a mother set her only son, choking to death of a fish-bone, at his feet, and the child was cured straight away. Regardless, the governor, unable to make Blaise renounce his faith, beat him with a stick, ripped his flesh with iron combs, and beheaded him.[6]

As the governor's men led Blaise back to Sebastea, on the way, they met a poor woman whose pig had been seized by a wolf. At the command of Blaise, the wolf restored the pig to its owner, alive and unhurt. When he had reached the capital and was thrown in prison to await execution, the old woman whose pig he had saved came to see him, bringing two fine wax candles to dispel the gloom of his dark cell. In the West, there had been no group honouring St. Blaise prior to the eighth century.[7]

The blessing of St. Blaise

[edit]

According to the Acts, while Blaise was being taken into custody, a distraught mother, whose only child was choking on a fish bone, threw herself at his feet and implored his intercession. Touched by her distress, he offered up his prayers, and the child was cured. Traditionally, Saint Blaise is invoked for protection against injuries and illnesses of the throat.

In many places, on the day of his feast the blessing of St. Blaise is given: two candles (sometimes lit), blessed on the feast of the Presentation of the Lord (Candlemas), are held in the form of a cross by a priest over the heads of the faithful or the people are touched on the throat with them.[8] At the same time the following blessing is given: "Through the intercession of Saint Blaise, bishop and martyr, may God deliver you from every disease of the throat and from every other illness". Then the priest makes the sign of the cross over the faithful.

Veneration of Saint Blaise

[edit]

One of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, Blaise became one of the most popular saints of the Middle Ages.[1] His followers became widespread in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries and his legend is recounted in the 13th-century Legenda Aurea. Saint Blaise is the saint of the wild beast.

He is patron of the Armenian Order of Saint Blaise. In Italy he is known as San Biagio. In Spanish-speaking countries, he is known as San Blas, and has lent his name to many places (see San Blas). Several places in Portugal and Brazil are also named after him, where he is called São Brás (see São Brás).

Many German churches, including the former Abbey of St. Blasius in the Black Forest and the church of Balve, are dedicated to Saint Blaise/Blasius.

In Croatia

[edit]

Saint Blaise (Croatian: Sveti Vlaho or Sveti Blaž) is the patron saint of the city of Dubrovnik and formerly the protector of the independent Republic of Ragusa. At Dubrovnik, his feast is celebrated yearly on 3 February, when relics of the saint, his skull, a bit of bone from his throat and his right and left hands are paraded in reliquaries. The festivities begin the previous day, Candlemas, when white doves are released. Chroniclers of Dubrovnik such as Rastic and Ranjina attribute his veneration there to a vision in 971 to warn the inhabitants of an impending attack by the Venetians, whose galleys had dropped anchor in Gruž and near Lokrum, ostensibly to resupply their water but furtively to spy out the city's defences. St. Blaise (Blasius) revealed their pernicious plan to Stojko, a canon of St. Stephen's Cathedral. The Senate summoned Stojko, who told them in detail how St. Blaise had appeared before him as an old man with a long beard and a bishop's mitre and staff. In this form, the effigy of Blaise remained on Dubrovnik's state seal and coinage until the Napoleonic era. Croatians all around the world celebrate the feast of Sveti Vlaho every year.

In Great Britain

[edit]

In Cornwall the town of St Blazey and the civil parish of St Blaise are derived from his name, where the parish church is still dedicated to Saint Blaise. The council of Oxford in 1222 forbade all work on his feast day.[9] There is a church dedicated to Saint Blaise in the Devon hamlet of Haccombe, near Newton Abbot, one at Shanklin on the Isle of Wight and another at Milton near Abingdon in Oxfordshire, one of the country's smallest churches. It is located next to Haccombe house which is the family home of the Carew family, descendants of the vice admiral on board the Mary Rose at the time of her sinking. This church, unusually, retains the office of an "archpriest".[10]

There is a St Blaise's Well in Bromley, London[11] where the water was considered to have medicinal virtues. St Blaise is also associated with Stretford in Lancashire. A Blessing of the Throats ceremony is held on February 3 at St Etheldreda's Church in London and in Balve, Germany. The blessing is performed in many Catholic parish churches, often at the end of a morning Mass.

The Blaise Castle Estate and the nearby Blaise Hamlet in Bristol derive their name from a thirteenth-century chapel dedicated to St Blaise, built on a site previously occupied by an Iron Age fort and a Roman temple.[12]

In Bradford, West Yorkshire a Catholic middle school named after St Blaise was operated by the Diocese of Leeds from 1961 to 1995. The name was chosen due to the connections of Bradford to the woollen industry and the method that St Blaise was martyred, with the woolcomb. Due to reorganisation, the school closed down when Catholic middle schools were phased out, and the building was sold to Bradford Council to provide replacement accommodation for another local middle school which had burned down. Within a few months, St Blaise school was also severely damaged in a fire, and the remains of the building were demolished. A new primary school was built on the land, and most of the extensive grounds were sold off for housing. There is a 14th-century wall painting of St Blaise in All Saints Church, Kingston upon Thames, located by the marketplace, marking the significance of the wool trade in the economic expansion of the market town in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Blaise and Blasius of Jersey

[edit]In England in the 18th and 19th centuries, Blaise was adopted as the mascot of woolworkers' pageants, particularly in Essex, Yorkshire, Wiltshire and Norwich. The popular enthusiasm for the saint is explained by the belief that Blaise had brought prosperity (as symbolised by the Woolsack) to England by teaching the English to comb wool. According to the tradition as recorded in printed broadsheets, Blaise came from Jersey, Channel Islands. Jersey was certainly a centre of export of woollen goods (as witnessed by the name jersey for the woollen textile). However, this legend is probably the result of confusion with a different saint, Blasius of Caesarea (Caesarea being also the Latin name of Jersey).

In Iceland

[edit]Blaise (Icelandic: Blasíus) was prominent in Iceland, in particular Southwestern Iceland, where he was known for his purported miracle-working powers.[13] Saint Blaise is mentioned in Þorláks saga helga, an Icelandic saga about Thorlak Thorhallsson, the patron saint of Iceland.[13]

In India

[edit]St. Blaise Church, Sao Bras, Goa, India was a small Chapel built in 1541 by Croatian sailors and traders settled in the village. It was elevated to a Parish Church in 1563. The church is a replica of the one in Dubrovnik, dedicated to St. Blaise, the patron of the city.[14]

In Italy

[edit]

In Italy, Saint Blaise's remains rest at the Basilica on Monte San Biagio, a mountain named in his honour, over the town of Maratea, Basilicata, shipwrecked there during Leo III the Isaurian's iconoclastic persecutions, on their first journey out of Sebastea to Europe.

In the small village of Sicilì in Campania, Saint Blaise’s feast day is celebrated on 3 February 3 but also on 14 May. Locals come to the shrine dedicated to him to show their respect and devotion but also to ask him for help with healing someone who has fallen ill where a special prayer is required.[15]

Iconography

[edit]In iconography, Blaise is represented holding two crossed candles in his hand (the Blessing of St. Blaise), or in a cave surrounded by wild beasts, as he was found by the hunters of the governor.[5] He is often shown with the instruments of his martyrdom, steel combs. The similarity of these instruments of torture to wool combs led to his adoption as the patron saint of wool combers in particular, and the wool trade in general. He may also be depicted with crossed candles. Such crossed candles are used for the blessing of throats on his feast day, which falls on 3 February, the day after Candlemas on the General Roman Calendar. Blaise is traditionally believed to intercede in cases of throat illnesses, especially for fish-bones stuck in the throat.[16] He is also called upon to aid in protection against obstructive sleep apnea since this involves the throat tissues interfering with breathing during sleep. (Non-OSA sleep disorders are typically invoked with the intercession of St. Dymphna since these are more neurological in nature.)

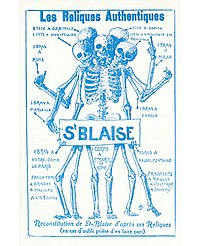

Relics

[edit]

There are multiple relics of Blaise in a variety of churches and chapels, including multiple whole bodies, at least four heads and several jaws, at least eight arms, and so on:[17][18]

With a little research, we would find Saint Blaise armed with a hundred arms, like the giant of the fable. The fingers, teeth, feet of this voluminous saint are too scattered for us to undertake to bring them together.

— Collin de Plancy, 1822[17]

See also

[edit]- Blessing of the Throats

- Order of Saint Blaise

- San Biagio (disambiguation)

- Saint Blaise, patron saint archive

- Festivity of Saint Blaise, the patron of Dubrovnik

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kirsch, Johann Peter. "St. Blaise." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 3 Feb. 2013

- ^ Marco Polo, Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian (1260-1295), I, ch. 46.

- ^ William Woodville Rockhill, ed., tr.The Journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55 1900:276.

- ^ a b "Life of St. Blaise, Bishop and Martyr", Colegio de Santa Catalina Alejandria Archived February 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Foley O.F.M., Leonard, "Saint Blaise", Saint of the Day, Lives, Lessons, and Feasts, (revised by Pat McCloskey O.F.M.), Franciscan Media ISBN 978-0-86716-887-7

- ^ Vollet, E. H., Grande Encyclopédie s.v. Blaise (Saint); published in Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca "Auctarium", 1969, 278, col. 665b.

- ^ "St. Blaise, Martyr", Lives of Saints, John J. Crawley & Co., Inc.

- ^ Latona, Mike (31 January 2022). "St. Blaise throat blessings offer physical, spiritual comfort". Catholic Courier. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911: "Blaise".

- ^ "Church of St Blaise". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Lysons, Daniel The Environs of London (Vol. 4), p. 307–323 (pub. 1796) - "British history online" (website).

- ^ Smith, Veronica, Street Names of Bristol, Broadcast Books, 2001

- ^ a b Cormack, Margaret (January 2014). "The Cult of St Blaise in Iceland". Saga-Book of the Viking Society.

- ^ "St. Blaise Church, Sao Bras, Goa".

- ^ (in Italian) Info about Festa di San Biagio

- ^ The formula for the blessing of throats is: "Per intercessionem Sancti Blasii, episcopi et martyris, liberet te Deus a malo gutturis, et a quolibet alio malo. In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. Amen." ("Through the intercession of St. Blaise, bishop and martyr, may God free you from illness of the throat and from any other sort of ill. In the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.)

- ^ a b Jacques-Albin-Simon Collin de Plancy, Dictionnaire critique des reliques et des images miraculeuses, 1822, p. 95-96 at Google Books Wikimedia Commons

Plancy's incomplete list: Body: Maratea, Rome, Brindisi, Ragusa, Volterra, Antwerp, Mechelen, Lisbon, Palermo. Large bones: Mende, Melun, Paris (2), Luxembourg, Maubeuge, Cambrai, Tournai, Ghent, Brages, Utrecht, Cologne (15+); Head: Naples, Saint-Maximin (Provence), Montpellier, Orbetello; Jaw: Douai, Ventimiglia, Bourbon-l'Archambault; Arms: Rome, Milan, Capua, Paris, Compostela, Dilighem in Brabant, Basse-Fontaine (Champagne), Marseille. - ^ Ludovic Lalanne. "Curiosities of Traditions, Customs and Legends" / p. 137 / In this book, Blaise: Body - 4, Head - 3, Arms - 8

External links

[edit]- Saint Blaise article from Catholic.org

- Hieromartyr Blaise of Sebaste

- St. Blaise's life in Voragine's Golden Legend: Latin original and English (English from the Caxton translation)

- Saint Blaise at the Christian Iconography web site.

- Novena in Honor of St. Blaise