Corpus luteum

| Corpus luteum | |

|---|---|

Section of the ovary. 1. Outer covering. 1’. Attached border. 2. Central stroma. 3. Peripheral stroma. 4. Bloodvessels. 5. Vesicular follicles in their earliest stage. 6, 7, 8. More advanced follicles. 9. An almost mature follicle. 9’. Follicle from which the ovum has escaped. 10. Corpus luteum. | |

| Details | |

| System | Reproductive system |

| Location | Ovary |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | corpus luteum |

| MeSH | D003338 |

| TA98 | A09.1.01.015 |

| TA2 | 3484 |

| FMA | 18619 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

The corpus luteum (Latin for "yellow body"; pl.: corpora lutea) is a temporary endocrine structure in female ovaries involved in the production of relatively high levels of progesterone, and moderate levels of estradiol, and inhibin A.[1][2] It is the remains of the ovarian follicle that has released a mature ovum during a previous ovulation.[3]

The corpus luteum is colored as a result of concentrating carotenoids (including lutein) from the diet and secretes a moderate amount of estrogen that inhibits further release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and thus secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). A new corpus luteum develops with each menstrual cycle.

Development and structure

[edit]The corpus luteum develops from an ovarian follicle during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle or oestrous cycle, following the release of a secondary oocyte from the follicle during ovulation. The follicle first forms a corpus hemorrhagicum before it becomes a corpus luteum, but the term refers to the visible collection of blood, left after rupture of the follicle, that secretes progesterone. While the oocyte (later the zygote if fertilization occurs) traverses the fallopian tube into the uterus, the corpus luteum remains in the ovary.[citation needed]

The corpus luteum is typically very large relative to the size of the ovary; in humans, the size of the structure ranges from under 2 cm to 5 cm in diameter.[4]

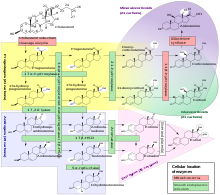

Its cells develop from the follicular cells surrounding the ovarian follicle.[5] The follicular theca cells luteinize into small luteal cells (thecal-lutein cells) and follicular granulosa cells luteinize into large luteal cells (granulosal-lutein cells) forming the corpus luteum. Progesterone is synthesized from cholesterol by both the large and small luteal cells upon luteal maturation. Cholesterol-LDL complexes bind to receptors on the plasma membrane of luteal cells and are internalized. Cholesterol is released and stored within the cell as cholesterol ester. LDL is recycled for further cholesterol transport. Large luteal cells produce more progesterone due to uninhibited/basal levels of protein kinase A (PKA) activity within the cell. Small luteal cells have LH receptors that regulate PKA activity within the cell. PKA actively phosphorylates steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and translocator protein to transport cholesterol from the outer mitochondrial membrane to the inner mitochondrial membrane.[6]

The development of the corpus luteum is accompanied by an increase in the level of the steroidogenic enzyme P450scc that converts cholesterol to pregnenolone in the mitochondria.[7] Pregnenolone is then converted to progesterone that is secreted out of the cell and into the blood stream. During the bovine estrous cycle, plasma levels of progesterone increase in parallel to the levels of P450scc and its electron donor adrenodoxin, indicating that progesterone secretion is a result of enhanced expression of P450scc in the corpus luteum.[7]

The mitochondrial P450 system electron transport chain including adrenodoxin reductase and adrenodoxin has been shown to leak electrons leading to the formation of superoxide radical.[8][9] Apparently to cope with the radicals produced by this system and by enhanced mitochondrial metabolism, the levels of antioxidant enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase also increase in parallel with the enhanced steroidogenesis in the corpus luteum.[7]

| Follicular structure | Luteal structure | Secretion |

|---|---|---|

| Theca cells | Theca lutein cells | androgens,[10] progesterone[10] |

| Granulosa cells | Granulosa lutein cells | progesterone,[5] estrogen(majority),[5] and inhibin A[5][10] |

Like the previous theca cells, the theca lutein cells lack the aromatase enzyme that is necessary to produce estrogen, so they can only perform steroidogenesis until formation of androgens. The granulosa lutein cells do have aromatase, and use it to produce estrogens, using the androgens previously synthesized by the theca lutein cells, as the granulosa lutein cells in themselves do not have the 17α-hydroxylase or 17,20 lyase to produce androgens.[5] Once the corpus luteum regresses the remnant is known as corpus albicans.[12]

Function

[edit]The corpus luteum is essential for establishing and maintaining pregnancy in females. The corpus luteum secretes progesterone, which is a steroid hormone responsible for the decidualization of the endometrium (its development) and maintenance, respectively. It also produces relaxin, a hormone responsible for softening of the pubic symphysis which helps in parturition.[13]

Unsuccessful fertilisation

[edit]If the egg is not fertilised, the corpus luteum stops secreting progesterone and decays (after approximately 10 days in humans). It then degenerates into a corpus albicans, which is a mass of fibrous scar tissue.[14]

With cessation of progesterone release, the uterine lining (functional, inner layer of the endometrium) is expelled through the vagina (in mammals that go through a menstrual cycle). Across an estrous cycle, the functional layer regenerates to provide nourishing tissue for potential fertilisation and implantation.[15][16]

Successful fertilisation

[edit]

If the egg is fertilised and implantation occurs, the syncytiotrophoblast (derived from trophoblast) cells of the blastocyst secrete the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, or a similar hormone in other species) by day 9 post-fertilisation.[citation needed]

Human chorionic gonadotropin signals the corpus luteum to continue progesterone secretion, thereby maintaining the thick lining (endometrium) of the uterus and providing an area rich in blood vessels in which the zygote(s) can develop. From this point on, the corpus luteum is called the corpus luteum graviditatis.[17]

The introduction of prostaglandins at this point causes the degeneration of the corpus luteum and the abortion of the fetus. However, in placental animals such as humans, the placenta eventually takes over progesterone production and the corpus luteum degrades into a corpus albicans without embryo/fetus loss.[citation needed]

Luteal support refers to the administration of medication (generally progestins) for the purpose of increasing the success of implantation and early embryogenesis, thereby complementing the function of the corpus luteum.

Content of carotenoids

[edit]The yellow color and name of the corpus luteum, like that of the macula lutea of the retina, is due to its concentration of certain carotenoids, especially lutein. In 1968, a report indicated that beta-carotene was synthesized in laboratory conditions in slices of corpus luteum from cows. However, attempts have been made to replicate these findings, but have not succeeded. The idea is not presently accepted by the scientific community.[18] Rather, the corpus luteum concentrates carotenoids from the diet of the mammal.

In animals

[edit]Similar structures and functions of the corpus luteum exist in some reptiles.[19] Dairy cattle also follow a similar cycle.[20]

Additional images

[edit]-

Order of changes in ovary

-

Human ovary with fully developed corpus luteum

-

Luteinized follicular cyst. H&E stain.

Pathology

[edit]- Corpus luteum cyst: hemorrhage into persistent corpus luteum. Commonly regresses spontaneously.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Histology Laboratory Manual". www.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Inquiry Into Biology (Textbook). McGraw-Hill Ryerson. 2007. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-07-096052-7.

- ^ Karch 2017, p. 657.

- ^ Vegetti W, Alagna F (2006). "FSH and follucogenesis: from physiology to ovarian stimulation". Reproductive biomedicine Online. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ a b c d e Boron 2005, p. 1300.

- ^ Niswender GD (March 2002). "Molecular control of luteal secretion of progesterone". Reproduction. 123 (3): 333–9. doi:10.1530/rep.0.1230333. PMID 11882010.

- ^ a b c Rapoport R, Sklan D, Wolfenson D, Shaham-Albalancy A, Hanukoglu I (March 1998). "Antioxidant capacity is correlated with steroidogenic status of the corpus luteum during the bovine estrous cycle". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1380 (1): 133–40. doi:10.1016/S0304-4165(97)00136-0. PMID 9545562.

- ^ Hanukoglu I, Rapoport R, Weiner L, Sklan D (September 1993). "Electron leakage from the mitochondrial NADPH-adrenodoxin reductase-adrenodoxin-P450scc (cholesterol side chain cleavage) system". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 305 (2): 489–98. doi:10.1006/abbi.1993.1452. PMID 8396893.

- ^ Rapoport R, Sklan D, Hanukoglu I (March 1995). "Electron leakage from the adrenal cortex mitochondrial P450scc and P450c11 systems: NADPH and steroid dependence". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 317 (2): 412–6. doi:10.1006/abbi.1995.1182. PMID 7893157.

- ^ a b c The IUPS Physiome Project --> Female Reproductive System – Cells Archived 2009-12-10 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on Nov 9, 2009

- ^ Häggström, Mikael; Richfield, David (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005. ISSN 2002-4436.

- ^ Marieb, Elaine (2013). Anatomy & physiology. Benjamin-Cummings. p. 915. ISBN 9780321887603.

- ^ Wang, Yan; Li, Yong-Qiang; Tian, Mei-Rong; Wang, Nan; Zheng, Zun-Cheng (2021-01-06). "Role of relaxin in diastasis of the pubic symphysis peripartum". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 9 (1): 91–101. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.91. ISSN 2307-8960. PMC 7809669. PMID 33511175.

- ^ Kirkendoll, Shelbie D.; Bacha, Dhouha (2023), "Histology, Corpus Albicans", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31424854, retrieved 2023-11-16

- ^ Critchley, Hilary O. D.; Babayev, Elnur; Bulun, Serdar E.; Clark, Sandy; Garcia-Grau, Iolanda; Gregersen, Peter K.; Kilcoyne, Aoife; Kim, Ji-Yong Julie; Lavender, Missy; Marsh, Erica E.; Matteson, Kristen A.; Maybin, Jacqueline A.; Metz, Christine N.; Moreno, Inmaculada; Silk, Kami (November 2020). "Menstruation: science and society". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 223 (5): 624–664. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.004. ISSN 1097-6868. PMC 7661839. PMID 32707266.

- ^ Campo, Hannes; Murphy, Alina; Yildiz, Sule; Woodruff, Teresa; Cervelló, Irene; Kim, J. Julie (July 2020). "Microphysiological Modeling of the Human Endometrium". Tissue Engineering. Part A. 26 (13–14): 759–768. doi:10.1089/ten.tea.2020.0022. ISSN 1937-335X. PMC 7398432. PMID 32348708.

- ^ Oliver, Rebecca; Pillarisetty, Leela Sharath (2023), "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Ovary Corpus Luteum", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30969526, retrieved 2023-11-16

- ^ Brian Davis. Carotenoid metabolism as a preparation for function. Pure and Applied Chemistry, Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 131–140, 1991. available online. Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine Accessed April 30, 2010.

- ^ Trauth, Stanley E. (1978). "Ovarian Cycle of Crotaphytus collaris (Reptilia, Lacertilia, Iguanidae) from Arkansas with Emphasis on Corpora Albicantia, Follicular Atresia, and Reproductive Potential". Journal of Herpetology. 12 (4): 461–470. doi:10.2307/1563350. ISSN 0022-1511. JSTOR 1563350.

- ^ Dairy cattle fertility & sterility. Fort Atkinson, Wis: W.D. Hoard & Sons. 1996. ISBN 978-0932147271.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Bibliography

[edit]- Karch, Amy (2017). Focus on nursing pharmacology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 9781496318213.

- Boron, Walter (2005). Medical physiology : a cellular and molecular approach. Philadelphia, Penns: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 18201loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Anatomy photo:43:05-0106 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "The Female Pelvis: The Ovary"

- CT of the abdomen showing a ruptured hemorrhagic copus luteal cyst