Invictus

| "Invictus" | |

|---|---|

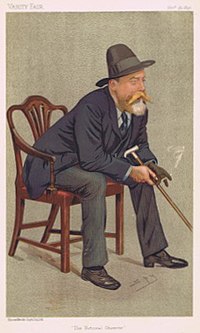

| Short story by William Ernest Henley | |

| |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Lyric poetry |

| Publication | |

| Publisher | Book of Verses |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 1888 |

"Invictus" is a short Victorian poem by the English poet William Ernest Henley (1849–1903). It was written in 1875 and published in 1888 in his first volume of poems, Book of Verses, in the section Life and Death (Echoes).[1]

Title

Originally, the poem was published with no title.[1] The second edition of Henley's Book of Verses added a dedication "To R. T. H. B."—a reference to Robert Thomas Hamilton Bruce (1846–1899), a successful Scottish flour merchant, baker, and literary patron.[2] The 1900 edition of Henley's Poems, published after Bruce's death, altered the dedication to "I. M. R. T. Hamilton Bruce (1846–1899)" (I. M. standing for "in memoriam").[3]

The poem was reprinted in nineteenth-century newspapers under a variety of titles, including "Myself",[4] "Song of a Strong Soul",[5] "My Soul",[6] "Clear Grit", [7] "Master of His Fate", [8] "Captain of My Soul", [9] "Urbs Fortitudinis", [10] and "De Profundis". [11]

The established title "Invictus" (Latin for "unconquered")[12] was added by editor Arthur Quiller-Couch when the poem was included in The Oxford Book of English Verse (1900).[13][14]

Text

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find me, unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.[1]

Importance

In 1875 one of Henley's legs required amputation due to complications arising from tuberculosis. Immediately after the amputation, he was told that his other leg would require a similar procedure. He chose instead to enlist the services of the distinguished English surgeon Joseph Lister, who was able to save Henley's remaining leg after multiple surgical interventions on the foot.[15] While recovering in the infirmary, he was moved to write the verses that became "Invictus". This period of his life, coupled with recollections of an impoverished childhood, were primary inspirations for the poem, and play a major role in its meaning.[16] A memorable evocation of Victorian stoicism—the "stiff upper lip" of self-discipline and fortitude in adversity, which popular culture rendered into a British character trait—"Invictus" remains a cultural touchstone.[17]

Sources

The fourth stanza alludes to a phrase from the King James Bible, which has, at Matthew 7:14,

Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

In modern English this is rendered as "But the gate to life is very narrow." In this context "life" means "eternal salvation."

Historical uses

- In a speech to the House of Commons on 9 September 1941, Winston Churchill paraphrased the last two lines of the poem, stating "We are still masters of our fate. We still are captains of our souls."[18]

- While incarcerated at Robben Island prison, Nelson Mandela recited the poem to other prisoners and was empowered by its message of self-mastery.[19][20]

- The Burmese opposition leader and Nobel Peace laureate [21] Aung San Suu Kyi stated, "This poem had inspired my father, Aung San, and his contemporaries during the independence struggle, as it also seemed to have inspired freedom fighters in other places at other times."[22]

- The poem was read by US POWs in North Vietnamese prisons. James Stockdale recalls being passed the last stanza, written with rat droppings on toilet paper, from fellow prisoner David Hatcher.[23]

- The line "bloody, but unbowed" was the Daily Mirror's headline the day after the 7 July 2005 London bombings.[24]

- The poem's last stanza was quoted by US President Barack Obama at the end of his speech at Nelson Mandela's memorial service (10 December 2013) in South Africa and published on the front cover of the December 14, 2013 issue of The Economist.[25]

- The poem was chosen by Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh as his final statement before his execution.[26][27]

- The poem was recited by students by the Eagle Academy during the 2016 United States National Democratic Convention.

Cultural references

- C. S. Lewis, in Book Five, chapter III (The Self-Sufficiency of Vertue) of his early autobiographical work The Pilgrim's Regress (1933) included a quote from the last two lines (paraphrased by the character "Vertue"): 'I cannot put myself under anyone's orders. I must be the captain of my soul and the master of my fate. But thank you for your offer.'.

- In Oscar Wilde's De Profundis letter in 1897, he reminisces that 'I was no longer the Captain of my soul'.

- In the 1942 film Casablanca, Captain Renault, an official played by Claude Rains, recites the last two lines of the poem when talking to Rick Blaine, played by Humphrey Bogart, referring to his power in Casablanca. After delivering this line, he is called away by an aide to Gestapo officer Major Strasser.[citation needed]

- In the 1960 film Sunrise at Campobello, the character Louis Howe, played by Hume Cronyn, reads the poem to Franklin D. Roosevelt, played by Ralph Bellamy. The recitation is at first light-hearted and partially in jest, but as it continues both men appear to realize the significance of the poem to Roosevelt's fight against his paralytic illness.

- The Invictus Games; an international Paralympic-style multi-sport event created by Prince Harry in which wounded, injured or sick armed services personnel and their associated veterans take part in sport, has featured the poem in its promotions. Prior to the inaugural games in London in 2014, entertainers including Daniel Craig and Tom Hardy, and athletes including Louis Smith and Iwan Thomas, read the poem in a promotional video.[28][29]

- In the 1942 film Kings Row, Parris Mitchell, a psychiatrist played by Robert Cummings, recites the first two stanzas of "Invictus" to his friend Drake McHugh, played by Ronald Reagan, before revealing to Drake that his legs were unnecessarily amputated by a cruel doctor.

- Mandela is depicted in the movie Invictus presenting a copy of the poem to Francois Pienaar, captain of the national South African rugby team, for inspiration during the Rugby World Cup—though at the actual event he gave Pienaar a text of "The Man in the Arena" passage from Theodore Roosevelt's Citizenship in a Republic speech delivered in France in 1910.[30]

- The line "bloody, but unbowed" was quoted by Lord Peter Wimsey in Dorothy Sayers' 1926 novel Clouds of Witness, in reference to his failure to exonerate his brother of the charge of murder.[31]

- The last two lines "I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul" are shown in a picture during the 25th minute of the film The Big Short.

- The second stanza is recited by Lieutenant-Commander Ashley Williams in the 2012 video game Mass Effect 3

- The line "I am the master of my fate... I am the captain of my soul" is used in Lana Del Rey's song "Lust for Life" featuring The Weeknd. The lyrics are changed from "I" to "we," alluding to a relationship.

- The poem was recited in an early commercial for the Microsoft Xbox One.

- In the US TV series The Blacklist episode "Ian Garvey" (No. 13), the eighth episode of the fifth season, Raymond 'Red' Reddington, played by James Spader, reads the poem to Elizabeth Keen, when she wakes up from a ten-month coma.

- In the US TV series One Tree Hill episode "Locked Hearts & Hand Grenades", the sixth episode of the third season, Lucas Scott, played by Chad Michael Murray, references the poem in an argument with Haley James Scott, played by Bethany Joy Lenz, over his heart condition and playing basket ball. The episode ends with Lucas reading the whole poem over a series of images that link the various characters to the themes of the poem.

See also

- If—, Rudyard Kipling

- The Man in the Arena, Theodore Roosevelt

- "Let No Charitable Hope[32]"—Elinor Wylie

References

- ^ a b c Henley, William Ernest (1888). A book of verses. London: D. Nutt. pp. 56–57. OCLC 13897970.

- ^ Henley, William Ernest (1891). A book of verses (Second ed.). New York: Scribner & Welford. pp. 56–7.

- ^ Henley, William Ernest (1900). Poems (Fourth ed.). London: David Nutt. p. 119.

- ^ "Myself". Weekly Telegraph. Sheffield (England). 1888-09-15. p. 587.

- ^ "Song of a Strong Soul". Pittsburgh Daily Post. Pittsburgh, PA. 1889-07-10. p. 4.

- ^ "My Soul". Lawrence Daily Journal. Lawrence, KS. 1889-07-12. p. 2.

- ^ "Clear Grit". Commercial Advertiser. Buffalo, NY. 1889-07-12. p. 2.

- ^ "Master of His Fate". Weekly Times-Democrat. New Orleans, LA. 1892-02-05. p. 8.

- ^ "Captain of My Soul". Lincoln Daily Call. Lincoln, NE. 1892-09-08. p. 4.

- ^ "Urbs Fortitudinis". Indianapolis Journal. Indianopolis, IN. 1896-12-06. p. 15.

- ^ "De Profundis". Daily World. Vancouver, BC. 1899-10-07. p. 3.

- ^ "English professor Marion Hoctor: The meaning of 'Invictus'". CNN. 2001-06-11. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Quiller-Couch, Arthur Thomas (ed.) (1902). The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250–1900 (1st (6th impression) ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1019. OCLC 3737413.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Wilson, A.N. (2001-06-11). "World of books". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ "Invictus analysis". jreed.eshs

- ^ "Biography of William Ernest Henley. Poetry Foundation

- ^ Spartans and Stoics - Stiff Upper Lip - Icons of England Archived 12 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 20 February 2011

- ^ "Famous Quotations and Stories". Winston Churchill.org.

- ^ Boehmer, Elleke (2008). "Nelson Mandela: a very short introduction". Oxford University Press.

Invictus, taken on its own, Mandela clearly found his Victorian ethic of self-mastery

- ^ Daniels, Eddie (1998) There and back

- ^ Independent, 8/30/17

- ^ Aung San Suu Kyi in BBC Reith Lecture, 2011-06-28

- ^ Stockdale, James (1993). "Courage Under Fire: Testing Epictetus's Doctrines in a Laboratory of Human Behavior" (PDF). Hoover Institution, Stanford.

- ^ "Bloodied but unbowed" mirror.co.uk

- ^ "The Economist Dec 14th, 2013". Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Quayle, Catherine (June 11, 2001). "Execution of an American Terrorist". Court TV.

- ^ Cosby, Rita (June 12, 2001). "Timothy McVeigh Put to Death for Oklahoma City Bombings". FOX News. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Daniel Craig, Tom Hardy & Will.i.am recite 'Invictus' to support the Invictus Games". YouTube. 29 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ "When are Prince Harry's Invictus Games and what are they?". The Daily Telegraph. 8 May 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ Dominic Sandbrook (30 January 2010). "British leaders: they're not what they were". The Daily Telegraph (UK).

- ^ Sayers, Dorothy (1943). Clouds of Witness. Classic Gems Publishing. p. 28. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ Wylie, Elinor (1932). "Let No Charitable Hope". Poetry Society of America.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)

External links

Works related to Invictus at Wikisource

Works related to Invictus at Wikisource